Armenians and Ottoman State Power, 1844-1896 by Richard Edward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

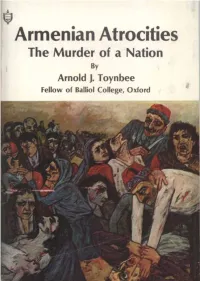

Armenian Atrocities the Murder of a Nation by Arnold J

Armenian Atrocities The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford as . $315. R* f*4 p i,"'a p 7; mt & H ps4 & ‘ ' -it f, Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford WITH A SPEECH DELIVERED BY LORD BRYCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION -_NEW YORK MONTREAL LONDON Copyright © 1975 by Tankian Publishing Corp. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-10955 International Standard Book Number: 0-87899-005-4 First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, 1917 First Tankian Publishing edition, 1975 Cover illustration: Original oil-painting by the renowned Franco-Armenian painter Zareh Mutafian, depicting the massacre of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915. TANKIAN TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES REGISTERED TRADEMARK - MARCA REGISTRADA PUBLISHED BY TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORP. G. P. O. BOX 678 -NEW YORK, N.Y. 10001 Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION 1915 - 1975 In commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Armenian massacres by the Turks which commenced April 24, 1915, we dedicate the republication of this historical document to the memory of the almost 2,000,000 Armenian martyrs who perished during this great tragedy. A MAP displaying THE SCENE OF THE ATROCITIES P Boundaries of Regions thus =-:-- ‘\ s « summer RailtMys ThUS.... ...... .... |/i ; t 0 100 isouuts % «DAMAS CUQ BAGHDAQ - & Taterw A C*] \ C marked on this with the of twelve for such of the s Every place map, exception deported Armeninians as reached as them, as waiting- included in square brackets, has been the scene of either depor- places for death. -

LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS When the BISHOP CELEBRATES MASS GENERAL LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS for EMCEES Before Mass: 1

DIOCESE OF BATON ROUGE LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS when the BISHOP CELEBRATES MASS GENERAL LITURGICAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR EMCEES Before Mass: 1. The pastor or his designate is responsible for setting up for the ceremony. The bishop must approve any changes from what is listed below. 2. Be certain all is prepared in the church, making sure all needed vessels and books are in place and correctly marked. Prepare sufficient hosts and wine so that the entire congregation will be able to receive Holy Communion consecrated at that Mass. The lectionary is placed on the ambo open to the first reading. Check the microphones and batteries! 3. Seats for concelebrating priests and servers are not to flank the bishop’s presidential chair, but instead be off to the side; the bishop’s presidential chair is to be arranged by itself. (Exception: one deacon, if present, sits on the bishop’s right; a second deacon if present may sit to the bishop’s left.) 4. The altar should be bare at the beginning of the celebration (excepting only the required altar cloth, and candles, which may be placed upon the altar). Corporals, purificators, books and other items are not placed on the altar until the Prepa- ration of the Gifts. 5. If incense is used, refer to note no. 2 in the “Liturgical Instructions for the Sacrament of Confirmation.” 6. Getting started on time is very important. Sometimes it is necessary to be assertive in order to get people moving. 7. Give the following directions to all concelebrating priests: a. During the Eucharistic Prayer, stand well behind and to the left and to the right of the bishop. -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA 6th May 2012 European Elections monitor Republican Party led by the President of the Republic Serzh Sarkisian is the main favourite in Corinne Deloy the general elections in Armenia. On 23rd February last the Armenian authorities announced that the next general elections would Analysis take place on 6th May. Nine political parties are running: the five parties represented in the Natio- 1 month before nal Assembly, the only chamber in parliament comprising the Republican Party of Armenia (HHK), the poll Prosperous Armenia (BHK), the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (HHD), Rule of Law (Orinats Erkir, OEK) and Heritage (Z), which is standing in a coalition with the Free Democrats of Khachatur Kokobelian, as well as the Armenian National Congress (HAK), the Communist Party (HKK), the Democratic Party and the United Armenians. The Armenian government led by Prime Minister Tigran Sarkisian (HHK) has comprised the Republi- can Party, Prosperous Armenia and Rule of Law since 21st March 2008. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation was a member of the government coalition until 2009 before leaving it because of its opposition to the government’s foreign policy. On 12th February last the Armenians elected their local representatives. The Republican Party led by President of the Republic Serzh Sarkisian won 33 of the 39 country’s towns. The opposition clai- med that there had been electoral fraud. The legislative campaign started on 8th April and will end on 4th May. 238 people working in Arme- nia’s embassies or consulates will be able to vote on 27th April and 1st May. The parties running Prosperous Armenia leader, Gagik Tsarukian will lead his The Republican Party will be led by the President of the party’s list. -

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour Conductor and Guide: Norayr Daduryan

Armenia 2020 June-11-22, 2020 Tour conductor and guide: Norayr Daduryan Price ~ $4,000 June 11, Thursday Departure. LAX flight to Armenia. June 12, Friday Arrival. Transport to hotel. June 13, Saturday 09:00 “Barev Yerevan” (Hello Yerevan): Walking tour- Republic Square, the fashionable Northern Avenue, Flower-man statue, Swan Lake, Opera House. 11:00 Statue of Hayk- The epic story of the birth of the Armenian nation 12:00 Garni temple. (77 A.D.) 14:00 Lunch at Sergey’s village house-restaurant. (included) 16:00 Geghard monastery complex and cave churches. (UNESCO World Heritage site.) June 14, Sunday 08:00-09:00 “Vernissage”: open-air market for antiques, Soviet-era artifacts, souvenirs, and more. th 11:00 Amberd castle on Mt. Aragats, 10 c. 13:00 “Armenian Letters” monument in Artashavan. 14:00 Hovhannavank monastery on the edge of Kasagh river gorge, (4th-13th cc.) Mr. Daduryan will retell the Biblical parable of the 10 virgins depicted on the church portal (1250 A.D.) 15:00 Van Ardi vineyard tour with a sunset dinner enjoying fine Italian food. (included) June 15, Monday 08:00 Tsaghkadzor mountain ski lift. th 12:00 Sevanavank monastery on Lake Sevan peninsula (9 century). Boat trip on Lake Sevan. (If weather permits.) 15:00 Lunch in Dilijan. Reimagined Armenian traditional food. (included) 16:00 Charming Dilijan town tour. 18:00 Haghartsin monastery, Dilijan. Mr. Daduryan will sing an acrostic hymn composed in the monastery in 1200’s. June 16, Tuesday 09:00 Equestrian statue of epic hero David of Sassoon. 09:30-11:30 Train- City of Gyumri- Orphanage visit. -

Komitas Piano and Chamber Music Seven Folk Dances • Seven Songs Twelve Children’S Pieces Based on Folk-Themes Msho-Shoror • Seven Pieces for Violin and Piano

includes WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS KOMITAS PIANO AND CHAMBER MUSIC SEVEN FOLK DANCES • SEVEN SONGS TWELVE CHILDREN’S PIECES BASED ON FOLK-THEMES MSHO-SHOROR • SEVEN PIECES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO MIKAEL AYRAPETYAN, piano VLADIMIR SERGEEV, violin KOMITAS (KOMITAS VARDAPET) 16 1 VLADIMIR SERGEEV Vladimir Sergeev was born in 1985 in Yaroslavl and started to learn the violin at the age of six. In 1996 he won KOMITAS (KOMITAS VARDAPET) (1869-1935) his first prize in a regional competition for young violinists and in 2000 PIANO AND CHAMBER MUSIC entered the Academic Music College SEVEN FOLK DANCES • SEVEN SONGS of the Moscow Tchaikovsky State TWELVE CHILDREN’S PIECES BASED ON FOLK-THEMES Conservatory as a student of People’s MSHO-SHOROR • SEVEN PIECES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO Artist of Georgia M.L. Yashvili. He was also trained by Yashvili at the MIKAEL AYRAPETYAN, piano Moscow Conservatory from 2004 to 2009, and in postgraduate studies VLADIMIR SERGEEV, violin until 2012. During his training, he became a laureate of the All-Russian competitions of Belgorod (1999) and Ryazan (2000) and in 2009 won Catalogue No.: GP720 the international St Petersburg Recording date: 15 December 2013 competition. Recording Venue: Great Hall, Moscow State University of Culture and Arts, Russia Producer: Mikael Ayrapetyan Engineer: Andrey Borisov Editions: Manuscripts Booklet Notes: Katy Hamilton German translation by Cris Posslac Cover Art: School Dash www.tonyprice.org 2 15 MIKAEL AYRAPETYAN SEVEN FOLK DANCES (1916) 1 No. 1 Manushaki of Vagharshapat 03:14 Mikael Ayrapetyan was born in 1984 2 No. 2 Yerangi of Yerevan 03:57 in Yerevan, Armenia, where he had 3 No. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

Crosier Generalate Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross Via Del Velabro 19, 00186 Rome, Italy

Crosier Generalate Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross Via del Velabro 19, 00186 Rome, Italy Letter of the Master General to present the Crosier Priesthood Profile A common question often asked by people is: “What is the distinctiveness of a Crosier priest as compared to other religious and secular priests?” It is a reasonable question. It flows from what people sense as the fundamental commonality shared among all religious and secular priests: sharing in Christ’s priesthood which then also demands a commitment to serving God and the People of God. There are differences and distinctions among priestly charisms exercised in the Church even all are founded on the one priesthood of Jesus Christ. Crosiers consequently should understand that religious priesthood (the identity as ordained ministers) is to be lived out in concert with the vows and the common life. We need to realize that the charism of the Order must be understood, internalized, and externalized in daily life. The values of our Crosier charism characterize our distinct way of being and serving within the concert of charisms in the Church and the Order of Presbyters. Our Crosier priesthood in an Order of Canons Regular should be colored by the elements of our Crosier religious life identity. This includes our lifelong commitment to fraternal community life, dedication to common liturgical prayer, and pastoral ministries that are energized by our religious life. For this reason, Crosiers commit to living out these living elements of our tradition; a heritage emphasized beginning in the years of novitiate and formation (see: Cons. -

Publications 1427998433.Pdf

THE CHURCH OF ARMENIA HISTORIOGRAPHY THEOLOGY ECCLESIOLOGY HISTORY ETHNOGRAPHY By Father Zaven Arzoumanian, PhD Columbia University Publication of the Western Diocese of the Armenian Church 2014 Cover painting by Hakob Gasparian 2 During the Pontificate of HIS HOLINESS KAREKIN II Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians By the Order of His Eminence ARCHBISHOP HOVNAN DERDERIAN Primate of the Western Diocese Of the Armenian Church of North America 3 To The Mgrublians And The Arzoumanians With Gratitude This publication sponsored by funds from family and friends on the occasion of the author’s birthday Special thanks to Yeretsgin Joyce Arzoumanian for her valuable assistance 4 To Archpriest Fr. Dr. Zaven Arzoumanian A merited Armenian clergyman Beloved Der Hayr, Your selfless pastoral service has become a beacon in the life of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Blessed are you for your sacrificial spirit and enduring love that you have so willfully offered for the betterment of the faithful community. You have shared the sacred vision of our Church fathers through your masterful and captivating writings. Your newest book titled “The Church of Armenia” offers the reader a complete historiographical, theological, ecclesiological, historical and ethnographical overview of the Armenian Apostolic Church. We pray to the Almighty God to grant you a long and a healthy life in order that you may continue to enrich the lives of the flock of Christ with renewed zeal and dedication. Prayerfully, Archbishop Hovnan Derderian Primate March 5, 2014 Burbank 5 PREFACE Specialized and diversified studies are included in this book from historiography to theology, and from ecclesiology to ethno- graphy, most of them little known to the public. -

Port Cities and Printers: Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian

Rqtv"Ekvkgu"cpf"Rtkpvgtu<"Tghngevkqpu"qp"Gctn{"Oqfgtp Inqdcn"Ctogpkcp"Rtkpv"Ewnvwtg Sebouh D. Aslanian Book History, Volume 17, 2014, pp. 51-93 (Article) Rwdnkujgf"d{"Vjg"Lqjpu"Jqrmkpu"Wpkxgtukv{"Rtguu DOI: 10.1353/bh.2014.0007 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bh/summary/v017/17.aslanian.html Access provided by UCLA Library (24 Oct 2014 19:07 GMT) Port Cities and Printers Reflections on Early Modern Global Armenian Print Culture Sebouh D. Aslanian Since the publication of Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin’s L’aparition du livre in 1958 and more recently Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979), a substantial corpus of scholarship has emerged on print culture, and even a new discipline known as l’histoire du livre, or history of the book, has taken shape.1 As several scholars have al- ready remarked, the bulk of the literature on book history and the history of print has been overwhelmingly Eurocentric in conception. In her magnum opus, for instance, Eisenstein hardly pauses to consider whether some of her bold arguments on the “printing revolution” are at all relevant for the world outside Europe, except perhaps for Euroamerica. As one scholar has noted, “until recently, the available literature on the non-European cases has been very patchy.”2 The recent publication of Jonathan Bloom’s Paper Before Print (2001),3 Mary Elizabeth Berry’s Japan in Print (2007), Nile Green’s essays on Persian print and his Bombay Islam,4 several essays and works in press on printing in South Asia5 and Ming-Qing China,6 and the convening of an important “Workshop on Print in a Global Context: Japan and the World”7 indicate, however, that the scholarship on print and book history is now prepared to embrace the “global turn” in historical studies. -

Varujan Vosganian, the Book of Whispers

Varujan Vosganian, The Book of Whispers Chapters seven and eight Translation: Alistair Ian Blyth Seven ‘Do not harm their women,’ said Armen Garo. ‘And nor the children.’ One by one, all the members of the Special Mission gathered at the offices of the Djagadamard newspaper in Constantinople. They had been selected with care. The group had been whittled down to those who had taken part in such operations before, working either alone or in ambush parties. ‘I trust only a man who has killed before,’ Armen Garo had declared. They were given photographs of those they were to seek out, wherever they were hiding. Their hiding places might be anywhere, from Berlin or Rome to the steppes of Central Asia. Broad-shouldered, bull-necked Talaat Pasha, the Minister of the Interior, was a brawny man, whose head, with its square chin and jaws that could rip asunder, was more like an extension of his powerful chest. In the lower part of the photograph, his fists, twice the size of a normal man’s, betokened pugnacity. Beside him, fragile, her features delicate, his wife wore a white dress and a lace cap in the European style, so very different from the pasha’s fez. Then there was Enver, a short man made taller by his boot heels. He had haughty eyes and slender fingers that preened the points of his moustache. He was proud of his army commander’s braids, which, cascading luxuriantly from his shoulders and covering his narrow chest, sought to disguise the humble beginnings of a son whose mother, in order to raise him, had plied one of the most despised trades in all the Empire: she had washed the bodies of the dead.