Suddensuccession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference After the 25Th of January Revolution)

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DERECHO INTERNACIONAL PÚBLICO Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES TESIS DOCTORAL Egyptian foreign policy (special reference after The 25th of January Revolution) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Rania Ahmed Hemaid DIRECTOR Najib Abu-Warda Madrid, 2018 © Rania Ahmed Hemaid, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Políticas Y Socioligía Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Doctoral Program Political Sciences PHD dissertation Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference after The 25th of January Revolution) POLÍTICA EXTERIOR EGIPCIA (ESPECIAL REFERENCIA DESPUÉS DE LA REVOLUCIÓN DEL 25 DE ENERO) Elaborated by Rania Ahmed Hemaid Under the Supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid Madrid, 2017 Ph.D. Dissertation Presented to the Complutense University of Madrid for obtaining the doctoral degree in Political Science by Ms. Rania Ahmed Hemaid, under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations, Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid. University: Complutense University of Madrid. Department: International Public Law and International Relations (International Studies). Program: Doctorate in Political Science. Director: Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda. Academic Year: 2017 Madrid, 2017 DEDICATION Dedication To my dearest parents may god rest their souls in peace and to my only family my sister whom without her support and love I would not have conducted this piece of work ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda for the continuous support of my Ph.D. -

Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and Its Crisis

crisis states research centre OCCASIONAL PAPERS Occasional Paper no. 3 Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council April 2007 ISSN 1753 3082 (online) Copyright © Alex de Waal, 2007 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Occasional Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Occasional Paper, or any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE 1 Crisis States Research Centre Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and its Crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council Overview This paper follows on from the associated essay, “Sudan: What Kind of State? What Kind of Crisis?”1 which concluded that the two dominant characteristics of the Sudanese state are (a) the extreme economic and political inequality between a hyper-dominant centre and peripheries that are weak and fragmented and (b) the failure of any single group or faction within the centre to exercise effective control over the institutions of the state, but who nonetheless can collectively stay in power because of their disproportionate resources. -

Spotlight on Sudan

REGIONAL PROGRAM POLITICAL DIALOGUE SOUTH MEDITERRANEAN FOREWORD At the crossroads between Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan is keeping pace with the political developments of the entire region. Yet, little studied, the country is not very visible to research institutions and think tanks due to difficult access to information. The recent developments that have brought Sudan to the forefront have also highlighted the extent to which this country of 42 million inhabitants has its destiny linked to the countries on the southern Mediterranean. Indeed, from the sending of Sudanese militiamen to Libya to the discussions on normalization with Israel through the numerous transactions with the Egyptian neighbor, Sudan is a country that impacts the southern Mediterranean in a deep and constant way. Furthermore, in addition to the internal ongoing conflicts, Sudan has found itself in the middle of the Nile river dispute between Ethiopia and its north African neighbor Egypt. Faced with this, and following a common reflection, the Regional Program Political Dialogue South Mediterranean of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung decided to open its geographical scope to Sudan and develop more knowledge about this country through various events and programs. SPOTLIGHT ON SUDAN In this sense, our regional program elaborated this study striving to highlight the recent developments in Sudan, its impact on the country’s neighbors and the geopolitical situation. Thomas Volk Director Regional Program Political Dialogue South Mediterranean -

International Human Rights Law Fall 2014

International Human Rights Law Fall 2014 Supplementary Readings (Supp.) Professor Schnably Contents Human Rights Committee, General Comment 20: Article 7 (Forty-fourth session, 1992), Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, U.N. Doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.6 at 151 (2003). ..................................................... 1 Atul Gawande, Hellhole: The United States holds tens of thousands of inmates in long-term solitary confinement. Is this torture? THE NEW YORKER, March 30, 2009 .......................................... 4 Yash Ghai, Universal Rights and Cultural Pluralism: Universalism and Relativism: Human Rights as a Framework for Negotiating Interethnic Claims, 21 CARDOZO L. REV. 1095 (2000) ................................................................................................................................................... 16 Abdullahi Ahmen An-Na’im, Human Rights in the Muslim World: Socio-Political Conditions and Scriptural Imperatives, 3 HARV. HUM. Rts. J. 13 (1990) .............................................................. 23 Materials and Questions on Cultural Relativism ........................................................................................ 29 Geoffrey Cowley, Gender Limbo, Newsweek, May 19, 1997, at 64 .......................................................... 32 UNHCR, Guidance Note on Refugee Claims Relating to Female Genital Mutilation, May 2009 (excerpts) ............................................................................................................................................. -

Safeguarding Sudan's Revolution

Safeguarding Sudan’s Revolution $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ 2FWREHU +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. From Crisis to Coup, Crackdown and Compromise ......................................................... 3 III. A Factious Security Establishment in a Time of Transition ............................................ 10 A. Key Players and Power Centres ................................................................................. 11 1. Burhan and the military ....................................................................................... 11 2. Hemedti and the Rapid Support Forces .............................................................. 12 3. Gosh and the National Intelligence and Security Services .................................. 15 B. Two Steps Toward Security Sector Reform ............................................................... 17 IV. The Opposition ................................................................................................................. 19 A. An Uneasy Alliance .................................................................................................... 19 B. Splintered Rebels ...................................................................................................... -

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs DECLARATION BY THE MINISTRY OF FOREIN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF THESLIDAN Pursuant to the republican decree no (148) of 2017 dated 2/3/2017 on the demarcation of the maritime baseline of the Republic of the Sudan on the Red Sea, and which was deposited with UN Secretary General on April 7th 2017, With reference to the declaration of the Government of the Sudan on its objection and rejection of the declaration of the Arab republic of Egypt dated 2nd of May 2017, on the demarcation of it's maritime boundaries, including coordinates which include the maritime zone of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle, as part of its borders, The Government of the Sudan declares it objection and rejection to what is known as the Agreement on the demarcation of maritime boundaries between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Arab Republic of Egypt signed on April 8th 2016, and which was deposited at the UN records (Treaty Section.. volume 5477), The Government of the Sudan, while objecting to the agreement, reaffirms its rejection to all that the agreement includes on the Delimitation of the Egyptian maritime boundaries which include coordinates of maritime areas that are an integral part of the maritime boundaries of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle , in consonance with the Sudan's complaint deposited with the UNSC since 1958,and which the Sudan has been renewing annually, and all the correspondences between the Government of the Sudan and the UN Secretary General and the UNSC, on the repeated attacks on the land and people of the Haleaeb Triangle by the Egyptian Occupying Authorities. -

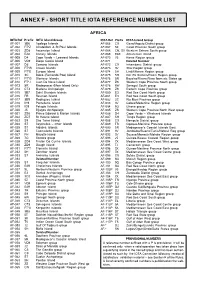

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

Violations of Articles 4 and 5

ALTERNATIVE REPORT To Sudan’s Periodic Report Before the 43rd Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Swaziland, May 2008) Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………. ……… 2 The Situation in Relation to Articles 4 and 5………………………………………….……………...................... 3 The Situation in Relation to Article 6………………………………………………………………….………......... 9 The Situation in Relation to Articles 7 and 26……………………………………………………………………… 12 The Situation in Relation to Article 9………………………………………………………………………….......... 16 The Situation in Relation to Articles 10 and 13……………………………………………………………………. 23 The Situation in Relation to Article 11………………………………………………………………………………. 27 The Situation in Relation to Article 18………………………………………………………………………………. 28 Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 33 Glossary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 35 SOAT is supported by and is a member of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) SOAT, Alternative Report to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, May 2008 1 Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Introduction Punishment (CAT), and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). As a signatory to Sudan ratified the African Charter on Human and these acts, Sudan is bound to refrain from acts which Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) on 18 February 1986. The would defeat their object and purpose. Sudanese government is therefore obliged to respect and protect the internationally recognised human Three years after the signing of the CPA, very little rights -

New Issues in Refugee Research

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Research Paper No. 254 Refugees and the Rashaida: human smuggling and trafficking from Eritrea to Sudan and Egypt Rachel Humphris Ph.D student COMPAS University of Oxford Email: [email protected] March 2013 Policy Development and Evaluation Service Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees P.O. Box 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates, as well as external researchers, to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction Eritreans have been seeking asylum in east Sudan for more than four decades and the region now hosts more than 100,000 refugees1. East Sudan has also become a key transit region for those fleeing Eritrea. One route, from East Sudan to Egypt, the Sinai desert and Israel has gained increasing attention. According to UNHCR statistics, the number of Eritreans crossing the border from Sinai to Israel has increased from 1,348 in 2006 to 17,175 in 2011. Coupled with this dramatic growth in numbers, the conditions on this route have caused great concern. Testimonies from Eritreans have increasingly referred to kidnapping, torture and extortion at the hands of human smugglers and traffickers. The smuggling route from Eritrea to Israel is long, complex and involves many different actors. As such, it cannot be examined in its entirety in a single paper. -

The Case of the Sudan's Power Relations

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2015 A Prince and a Fractured Kingdom: The Case of the Sudan’s Power Relations Jihad Salih Mashamoun Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Salih Mashamoun, J. (2015).A Prince and a Fractured Kingdom: The Case of the Sudan’s Power Relations [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/63 MLA Citation Salih Mashamoun, Jihad. A Prince and a Fractured Kingdom: The Case of the Sudan’s Power Relations. 2015. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/63 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences A Prince and a Fractured Kingdom: The Case of the Sudan’s Power Relations A Thesis Submitted to The Political Science Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for A Master of Arts Degree By Jihad Salih Mashamoun Under the supervision of Dr. Nadia Farah April 30,2015 Table of Contents Dedication……………………………………………………………………………v Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………...vi Acronyms………………………………………………………………………………………….. vii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...xi Introduction…………………………………………………………………………...1 -

DARFUR – Dimensions and Dilemmas of a Complex Situation Johan Brosché

Department of Peace and Conflict Research Johan Brosché DARFUR – Dimensions and Dilemmas of a Complex Situation Johan Brosché DARFUR – Dimensions and Dilemmas of a Complex Situation Uppsala University Department of Peace and Conflict Research UCDP Paper No. www.ucdp.uu.se Department of Peace and Conflict Research Uppsala University Box 51 S 751 0 Uppsala Sweden www.pcr.uu.se Darfur– Dimensions and Dilemmas of a Complex Situation Copyright © 2008 Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. All rights reserved. Cover photos: ©Johannes Saers, all rights reserved Cover design, layout and typesetting: Maria Wold-Troell Printed in Sweden by Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala, 2008 ISBN 978-91-506-1991-1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ ......... i Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................ii Policy recommendations ...........................................................................................................v Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................viii 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................1 . Backgound and Comprehensive View of Sudan .......................................... Background on Sudan ..................................................................................