Spotlight on Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

The Eastern Front and the Struggle Against Marginalization

3 The Eastern Front and the Struggle against Marginalization By John Young Copyright The Small Arms Survey Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It serves © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2007 as the principal source of public information on all aspects of small arms and First published in May 2007 as a resource centre for governments, policy-makers, researchers, and activ- ists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Depart- permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by ment of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Bel- law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- gium, Canada, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should United Kingdom. The Survey is also grateful for past and current project-spe- be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. cific support received from Australia, Denmark, and New Zealand. Further Small Arms Survey funding has been provided by the United Nations Development Programme, Graduate Institute of International Studies the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, the Geneva 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland International Academic Network, and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining. -

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa

SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 1 SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage In the Middle East and North Africa UNICEF Middle East and North Africa Regional Oce This report was developed in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and funded by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The views expressed and information contained in the report are not necessarily those of, or endorsed by, UNICEF. Acknowledgements The development of this report was a joint effort with UNICEF regional and country offices and partners, with contributions from UNFPA. Thanks to UNICEF and UNFPA Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan, Morocco and Egypt Country and Regional Offices and their partners for their collaboration and crucial inputs to the development of the report. Proposed citation: ‘Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa – Sudan Country Brief’, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Middle East and North Africa Regional Office in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (IRCW), 2017. SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 3 4 SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage SUDAN Regional Study on Child Marriage Key Recommendations Girls’ Voice and Agency Build capacity of women parliamentarians to effectively Provide financial incentives for sending girls raise and defend women-related issues in the parliament. to school through conditional cash transfers. Increase funding to NGOs for child marriage-specific programming. Household and Community Attitudes and Behaviours Engage receptive religious leaders through Legal Context dialogue and awareness workshops, and Coordinate advocacy efforts to end child marriage to link them to other organizations working on ensure the National Strategy is endorsed by the gov- child marriage, such as the Medical Council, ernment, and the Ministry of Justice completes its re- CEVAW and academic institutions. -

Sudan National Report

REPUBLIC OF THE SUDSN MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC PLANNING IMPLEMENTATION OF ISTANBOUL PLAN OF ACTION FOR LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES (IPoA) 2011-2020 SUDAN NATIONAL REPORT Khartoum October 2019 Contents I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 III. The National Development Planning Process .................................................................................. 5 IV. Assessment of Progress and Challenges in the Implementation of the Istanbul Program of Action for the Decade 2011-2020 ............................................................................................................................ 7 a) Productive Capacity ......................................................................................................................... 7 b) Agriculture, Food Security and Rural Development ...................................................................... 16 c) Trade .............................................................................................................................................. 17 d) Commodities .................................................................................................................................. 19 e) Private Sector Development .......................................................................................................... -

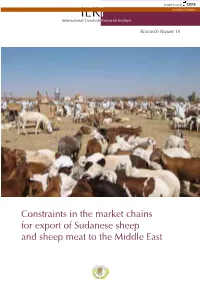

Constraints in the Market Chains for Export of Sudanese Sheep and Sheep Meat to the Middle East

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE ILRI provided by CGSpace International Livestock Research Institute Research Report 16 Constraints in the market chains for export of Sudanese sheep and sheep meat to the Middle East ISBN 92–9146–195–4 Constraints in the market chains for export of Sudanese sheep and sheep meat to the Middle East Omar Hassan el Dirani, Mohammad A Jabbar and Babiker Idris Babiker Ministry of Animal Resources and Fisheries ILRI International Livestock Research Institute INTERNATIONAL LIVESTOCK RESEARCH INSTITUTE i Authors’ affiliations Omar Hassan el Dirani, Ministry of Animal Resources and Fisheries, Government of Sudan, Khartoum, the Sudan Mohammad A Jabbar, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, Kenya Babiker Idris Babiker, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, the Sudan © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. ISBN 92–9146–195–4 Correct citation: el Dirani OH, Jabbar MA and Babiker IB. 2009. Constraints in the market chains for export of Sudanese sheep and sheep meat to the Middle East. Research Report 16. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, the Sudan, and ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Nairobi, -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elghawary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Suddensuccession

SUDDEN SUCCESSION Examining the Impact of Abrupt Change in the Middle East SIMON HENDERSON KRISTIAN C. ULRICHSEN EDITORS MbZ and the Future Leadership of the United Arab Emirates IN PRACTICE, Sheikh Muhammad bin Zayed al-Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, is already the political leader of the United Arab Emirates, even though the federation’s president, and Abu Dhabi’s leader, is his elder half-brother Sheikh Khalifa. This study examines leadership in the UAE and what might happen if, for whatever reason, Sheikh Muham- mad, widely known as MbZ, does not become either the ruler of Abu Dhabi or president of the UAE. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ POLICY NOTE 65 ■ JULY 2019 SUDDEN SUCCESSION: UAE RAS AL-KHAIMAH UMM AL-QUWAIN AJMAN SHARJAH DUBAI FUJAIRAH ABU DHABI ©1995 Central Intelligence Agency. Used by permission of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Formation of the UAE moniker that persisted until 1853, when Britain and regional sheikhs signed the Treaty of Maritime Peace The UAE was created in November 1971 as a fed- in Perpetuity and subsequent accords that handed eration of six emirates—Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, responsibility for conduct of the region’s foreign rela- Fujairah, Ajman, and Umm al-Quwain. A seventh— tions to Britain. When about a century later, in 1968, Ras al-Khaimah—joined in February 1972 (see table Britain withdrew its presence from areas east of the 1). The UAE’s two founding leaders were Sheikh Suez Canal, it initially proposed a confederation that Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan (1918–2004), the ruler would include today’s UAE as well as Qatar and of Abu Dhabi, and Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed al-Mak- Bahrain, but these latter two entities opted for com- toum (1912–90), the ruler of Dubai. -

The Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan1 - Summary and Analysis

[DRAFT] [NOT FOR CIRCULATION] International IDEA The Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan1 - Summary and Analysis - 1. Executive summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 2. Context .......................................................................................................................................... 3 (a) This Paper ............................................................................................................................. 3 (b) The Agreement ..................................................................................................................... 3 (c) The Parties ........................................................................................................................... 6 3. Content of the future constitution ................................................................................................ 8 (a) Federalism ............................................................................................................................ 8 (b) Financial issues and revenue sharing .................................................................................. 13 (c) Individual and the state ...................................................................................................... 15 4. Transitional issues ....................................................................................................................... 16 (a) Transitional period............................................................................................................. -

Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and Its Crisis

crisis states research centre OCCASIONAL PAPERS Occasional Paper no. 3 Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council April 2007 ISSN 1753 3082 (online) Copyright © Alex de Waal, 2007 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Occasional Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Occasional Paper, or any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE 1 Crisis States Research Centre Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and its Crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council Overview This paper follows on from the associated essay, “Sudan: What Kind of State? What Kind of Crisis?”1 which concluded that the two dominant characteristics of the Sudanese state are (a) the extreme economic and political inequality between a hyper-dominant centre and peripheries that are weak and fragmented and (b) the failure of any single group or faction within the centre to exercise effective control over the institutions of the state, but who nonetheless can collectively stay in power because of their disproportionate resources. -

Usipeace Briefing Peacemaking and Peacebuilding in Eastern Sudan by Dorina Bekoe and Nirina Kiplagat September 2006

Peacemaking and Peacebuilding in Eastern Sudan by Dorina Bekoe and Nirina Kiplagat: ... Page 1 of 7 USIPeace Briefing Peacemaking and Peacebuilding in Eastern Sudan By Dorina Bekoe and Nirina Kiplagat September 2006 Drivers of Conflict in Eastern Sudan Lessons from the Comprehensive and Darfur Peace Agreements Key Actors and their Roles and Responses to Eastern Sudan's Crises The Way Forward for Peace and Stability in Eastern Sudan The Beja Congress and Free Lions rebel movements in eastern Sudan1 have waged a low-intensity conflict since 1997, alleging that the government has marginalized the region politically, socially, and economically. In January 2005, there were fears that the conflict would intensify (after the armed forces of the government of Sudan (GOS) killed demonstrators in the city of Port Sudan). Fortunately, the conflict did not escalate; on the whole violence in eastern Sudan has been kept to minimal levels. In June 2006, the Eastern Front—a coalition of the Beja Congress and the Free Lions—and the GOS entered into formal peace talks in Asmara, Eritrea. The government of Eritrea serves as mediator to the talks. To understand the drivers of conflict and the keys to sustainable peace in eastern Sudan, the United States Institute of Peace, in partnership with the Nairobi Peace Initiative-Africa, hosted a workshop entitled "Listening to East Sudan: Assessing the Social and Economic Stresses, Mobilising Responses" in Nairobi, Kenya, from August 21 to 23, 2006. Seventeen representatives from a cross-section of Sudanese civil society organisations and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) attended. On September 20, a meeting of the Institute's Sudan Peace Forum, which comprises policy and academic experts on Sudan, took place as a follow-up to the Nairobi workshop. -

Sudan, Performed by the Much Loved Singer Mohamed Wardi

Confluence: 1. the junction of two rivers, especially rivers of approximately equal width; 2. an act or process of merging. Oxford English Dictionary For you oh noble grief For you oh sweet dream For you oh homeland For you oh Nile For you oh night Oh good and beautiful one Oh my charming country (…) Oh Nubian face, Oh Arabic word, Oh Black African tattoo Oh My Charming Country (Ya Baladi Ya Habbob), a poem by Sidahmed Alhardallou written in 1972, which has become one of the most popular songs of Sudan, performed by the much loved singer Mohamed Wardi. It speaks of Sudan as one land, praising the country’s diversity. EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUDANESE ORGANISATION FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT In Search of Confluence Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Sudan The Equal Rights Trust Country Report Series: 4 London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose pur- pose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust © Photos: Anwar Awad Ali Elsamani © Cover October 2014 Dafina Gueorguieva Layout: Istvan Fenyvesi PrintedDesign: in Dafinathe UK Gueorguieva by Stroma Ltd ISBN: 978-0-9573458-0-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA.