Rail, Steam, and Speed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birthday Parties

£95 for 30 people 30 for £95 £65 for 20 people 20 for £65 Prices head. Please ask for further details. further for ask Please head. supplied by Megabites of Rothwell, from £5 per per £5 from Rothwell, of Megabites by supplied If you wish we can provide food for your party, party, your for food provide can we wish you If new castings for old, missing and broken parts. broken and missing old, for castings new See our collection of historic patterns used to make make to used patterns historic of collection our See are available at the Moor Road shop. Road Moor the at available are Hot and cold drinks and confectionery confectionery and drinks cold and Hot and let the children have fun in the play area. play the in fun have children the let and food for consumption on the train or at Park Halt Halt Park at or train the on consumption for food have a go operating the model train model the operating go a have You are welcome to bring your own own your bring to welcome are You Relax in our cafe with a hot drink and a sandwich, a and drink hot a with cafe our in Relax See the inside of a boiler and learn how it works. it how learn and boiler a of inside the See of a steam locomotive steam a of locomotive and preparing it for your journey ahead. journey your for it preparing and locomotive Climb onto the footplate and learn the controls controls the learn and footplate the onto Climb Watch the crew undertake their duties, caring for the the for caring duties, their undertake crew the Watch Halt and Moor Road after each trip. -

Tees Valley Contents

RELOCATING TO THE TEES VALLEY CONTENTS 3. Introduction to the Tees Valley 4. Darlington 8. Yarm & Eaglescliffe 10. Marton & Nunthorpe 12. Guisborough 14. Saltburn 16. Wynyard & Hartlepool THE TEES VALLEY Countryside and coast on the doorstep; a vibrant community of creative and independent businesses; growing industry and innovative emerging sectors; a friendly, upbeat Northern nature and the perfect location from which to explore the neighbouring beauty of the North East and Yorkshire are just a few reasons why it’s great to call the Tees Valley home. Labelled the “most exciting, beautiful and friendly region in The Tees Valley provides easy access to the rest of the England” by Lonely Planet, the Tees Valley offers a fantastic country and international hubs such as London Heathrow and quality of life to balance with a successful career. Some of the Amsterdam Schiphol, with weekends away, short breaks and UK’s most scenic coastline and countryside are just a short summer holidays also within easy reach from our local Teesside commute out of the bustling town centres – providing the International Airport. perfect escape after a hard day at the office. Country and coastal retreats are close-by in Durham, Barnard Nestled between County Durham and North Yorkshire, the Tees Castle, Richmond, Redcar, Seaton Carew, Saltburn, Staithes and Valley is made up of Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Whitby and city stopovers in London, Edinburgh and Manchester Redcar & Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees. are a relaxing two-and-a-half-hour train journey away. Newcastle, York, Leeds and the Lake District are also all within an hour’s The region has a thriving independent scene, with bars, pubs drive. -

Performance and Scaling Analysis of a Hypocycloid Wiseman Engine By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Performance and Scaling Analysis of a Hypocycloid Wiseman Engine by Priyesh Ray A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Technology Approved April 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Sangram Redkar, Chair Abdel Ra'ouf Mayyas Robert Meitz ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2014 ABSTRACT The slider-crank mechanism is popularly used in internal combustion engines to convert the reciprocating motion of the piston into a rotary motion. This research discusses an alternate mechanism proposed by the Wiseman Technology Inc. which involves replacing the crankshaft with a hypocycloid gear assembly. The unique hypocycloid gear arrangement allows the piston and the connecting rod to move in a straight line, creating a perfect sinusoidal motion. To analyze the performance advantages of the Wiseman mechanism, engine simulation software was used. The Wiseman engine with the hypocycloid piston motion was modeled in the software and the engine’s simulated output results were compared to those with a conventional engine of the same size. The software was also used to analyze the multi-fuel capabilities of the Wiseman engine using a contra piston. The engine’s performance was studied while operating on diesel, ethanol and gasoline fuel. Further, a scaling analysis on the future Wiseman engine prototypes was carried out to understand how the performance of the engine is affected by increasing the output power and cylinder displacement. It was found that the existing Wiseman engine produced about 7% less power at peak speeds compared to the slider-crank engine of the same size. -

Archaeology in Northumberland Friends

100 95 75 Archaeology 25 5 in 0 Northumberland 100 95 75 25 5 0 Volume 20 Contents 100 100 Foreword............................................... 1 95 Breaking News.......................................... 1 95 Archaeology in Northumberland Friends . 2 75 What is a QR code?...................................... 2 75 Twizel Bridge: Flodden 1513.com............................ 3 The RAMP Project: Rock Art goes Mobile . 4 25 Heiferlaw, Alnwick: Zero Station............................. 6 25 Northumberland Coast AONB Lime Kiln Survey. 8 5 Ecology and the Heritage Asset: Bats in the Belfry . 11 5 0 Surveying Steel Rigg.....................................12 0 Marygate, Berwick-upon-Tweed: Kilns, Sewerage and Gardening . 14 Debdon, Rothbury: Cairnfield...............................16 Northumberland’s Drove Roads.............................17 Barmoor Castle .........................................18 Excavations at High Rochester: Bremenium Roman Fort . 20 1 Ford Parish: a New Saxon Cemetery ........................22 Duddo Stones ..........................................24 Flodden 1513: Excavations at Flodden Hill . 26 Berwick-upon-Tweed: New Homes for CAAG . 28 Remapping Hadrian’s Wall ................................29 What is an Ecomuseum?..................................30 Frankham Farm, Newbrough: building survey record . 32 Spittal Point: Berwick-upon-Tweed’s Military and Industrial Past . 34 Portable Antiquities in Northumberland 2010 . 36 Berwick-upon-Tweed: Year 1 Historic Area Improvement Scheme. 38 Dues Hill Farm: flint finds..................................39 -

The Journal of the Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway

The Globe The Journal of the Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway Issue 4 December 2017 The Globe is named after Timothy Hackworth’s locomotive which was commissioned by the S&DR specifically to haul passengers between Darlington and Middlesbrough in 1829. The Globe was also the name of a newspaper founded in 1803 by Christopher Blackett. Blackett was a coal mining entrepreneur from Wylam with a distinguished record in the evolution of steam engines. All text and photographs are copyright Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway and authors except where clearly marked as that of others. Opinions expressed in the journal may be those of individual authors and not of the Friends of the S&DR Please send contributions to future newsletters to [email protected]. The deadline for the next issue of The Globe is 2nd April 2018. CONTENTS Chair’s welcome 1 Who we are and what we do 2 Thomas Greener and his model steam engine 2 Membership 3 News 3 Railway history over a barrel 11 Events 12 Found! (And Lost). The S&DR Mystery Brewery 13 Planning to Protect the S&DR 22 Brusselton Engine House 25 Getting in touch…. Chair Trish Pemberton [email protected] Vice Chair Niall Hammond [email protected] President Lord Foster of Bishop Auckland [email protected] Vice President Chris Lloyd [email protected] Secretary Alan Macnab [email protected] Asst Secretary Alan Townsend [email protected] Treasurer Susan Macnab susan.macnab@ntlworld. com Membership Secretary Peter Bainbridge [email protected] -

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. the LOCOMOTIVE

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. THE LOCOMOTIVE. GEORGE AND ROBERT STEPHENSON. BY SAMUEL SMILES, INTRODUCTION. Since the appearance of this book in its original form, some seventeen years since, the construction of Railways has continued to make extraordinary progress. Although Great Britain, first in the field, had then, after about twenty-five years‘ work, expended nearly 300 millions sterling in the construction of 8300 miles of railway, it has, during the last seventeen years, expended about 288 millions more in constructing 7780 additional miles. But the construction of railways has proceeded with equal rapidity on the Continent. France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, have largely added to their railway mileage. Austria is actively engaged in carrying new lines across the plains of Hungary, which Turkey is preparing to meet by lines carried up the valley of the Lower Danube. Russia is also occupied with extensive schemes for connecting Petersburg and Moscow with her ports in the Black Sea on the one hand, and with the frontier towns of her Asiatic empire on the other. Italy is employing her new-born liberty in vigorously extending railways throughout her dominions. A direct line of communication has already been opened between France and Italy, through the Mont Cenis Tunnel; while p. ivanother has been opened between Germany and Italy through the Brenner Pass,—so that the entire journey may now be made by two different railway routes excepting only the short sea-passage across the English Channel from London to Brindisi, situated in the south-eastern extremity of the Italian peninsula. During the last sixteen years, nearly the whole of the Indian railways have been made. -

Boiler Feed Water Treatment

Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed B.Sc. (Honours) in Textile Engineering Technology University of Gezira (2006) A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Gezira in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science In Chemical Engineering Department of Applied Chemistry and Chemical Technology Faculty of Engineering and Technology University of Gezira January,2014 I Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Supervision Committee: Name Position Signature Dr. Bshir Mohammed Elhassen Main Supervisor …………………. Dr. Mohammed Osman Babiker Co-supervisor ………………….. Date : January , 2014 II Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Shareef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Examination Committee: Name Position Signature Dr. Bshir Mohammed Elhassen Chair Person ……………… Dr.Bahaaeldeen Siddig Mohammed External Examiner ………………… Dr. Mustafa Ohag Mohammed Internal Examiner ………………… Date of Examination : 6. January.2014 III Dedication This research is affectionately dedicated to the souls of my parents , To my family With gratitude and love To whom ever love knowledge I Acknowledgment I would like to thank Dr. Basher Mohammed Elhassan the main Supervisor for his guidance and help. my thank also extended to Dr. Mohammed Osman Babiker my Co-supervisor for his great help. my thanks also extended to Chemical Engineers in Dr. Mohamod Sharef Thermal Power Station. II Boiler Feed Water Treatment: A case Study Of Dr. Mohamod Sharef Thermal Power Station, Khartoum State, Sudan Motawakel Sayed Osman Mohammed Ahmed Abstract A boiler is an enclosed vessel that provides a means for combustion heat to be transferred to water until it becomes heated water or steam. -

The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive, 1803 to 1898 (1899)

> g s J> ° "^ Q as : F7 lA-dh-**^) THE EVOLUTION OF THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE (1803 to 1898.) BY Q. A. SEKON, Editor of the "Railway Magazine" and "Hallway Year Book, Author of "A History of the Great Western Railway," *•., 4*. SECOND EDITION (Enlarged). £on&on THE RAILWAY PUBLISHING CO., Ltd., 79 and 80, Temple Chambers, Temple Avenue, E.C. 1899. T3 in PKEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. When, ten days ago, the first copy of the " Evolution of the Steam Locomotive" was ready for sale, I did not expect to be called upon to write a preface for a new edition before 240 hours had expired. The author cannot but be gratified to know that the whole of the extremely large first edition was exhausted practically upon publication, and since many would-be readers are still unsupplied, the demand for another edition is pressing. Under these circumstances but slight modifications have been made in the original text, although additional particulars and illustrations have been inserted in the new edition. The new matter relates to the locomotives of the North Staffordshire, London., Tilbury, and Southend, Great Western, and London and North Western Railways. I sincerely thank the many correspondents who, in the few days that have elapsed since the publication: of the "Evolution of the , Steam Locomotive," have so readily assured me of - their hearty appreciation of the book. rj .;! G. A. SEKON. -! January, 1899. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. In connection with the marvellous growth of our railway system there is nothing of so paramount importance and interest as the evolution of the locomotive steam engine. -

Passenger Rail (Edited from Wikipedia)

Passenger Rail (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY A passenger train travels between stations where passengers may embark and disembark. The oversight of the train is the duty of a guard/train manager/conductor. Passenger trains are part of public transport and often make up the stem of the service, with buses feeding to stations. Passenger trains provide long-distance intercity travel, daily commuter trips, or local urban transit services. They even include a diversity of vehicles, operating speeds, right-of-way requirements, and service frequency. Passenger trains usually can be divided into two operations: intercity railway and intracity transit. Whereas as intercity railway involve higher speeds, longer routes, and lower frequency (usually scheduled), intracity transit involves lower speeds, shorter routes, and higher frequency (especially during peak hours). Intercity trains are long-haul trains that operate with few stops between cities. Trains typically have amenities such as a dining car. Some lines also provide over-night services with sleeping cars. Some long-haul trains have been given a specific name. Regional trains are medium distance trains that connect cities with outlying, surrounding areas, or provide a regional service, making more stops and having lower speeds. Commuter trains serve suburbs of urban areas, providing a daily commuting service. Airport rail links provide quick access from city centers to airports. High-speed rail are special inter-city trains that operate at much higher speeds than conventional railways, the limit being regarded at 120 to 200 mph. High-speed trains are used mostly for long-haul service and most systems are in Western Europe and East Asia. -

Head of Steam Events 2019.Pdf

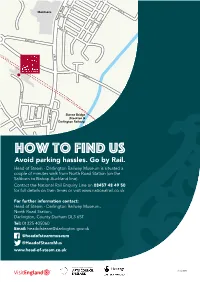

Shildon St Henry St Charles St James St Morrisons Aldam St North Road Gurney St Katherine St Edmund St Whessoe Rd A167 Albert Rd Hopetown Ln Station Rd McNay St Skerne Bridge Stephenson St (Stockton & North Road Darlington Railway) Station Rd Station Arthur St HowStation Rd to find us Avoid parking hassles. Go by Rail. Head of Steam - Darlington Railway Museum is situated a couple of minutes walk from North Road Station (on the Saltburn to Bishop Auckland line). Contact the National Rail Enquiry Line on 08457 48 49 50 for full details on train times or visit www.nationalrail.co.uk For further information contact: Head of Steam - Darlington Railway Museum, North Road Station, Darlington, County Durham DL3 6ST. Tel: 01325 405060 Email: [email protected] @headofsteammuseum @HeadofSteamMus www.head-of-steam.co.uk dnsr0680 head of steam Darlington Railway Museum EVENTS 2019 Head of Steam Events 2019 Tel: 01325 405060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.head-of-steam.co.uk The Afternoon Lectures: Thursday 10th January 2019 at 1.45pm Meeting Room ‘Darlington Railway Museum – A Review and Preview’ Come along for an update on our plans for the coming year, and find out more about the Friends of the Museum. FREE to members of the Friends, non-members welcome, (please telephone the museum for membership or price details). Nostalgia of Steam Saturday 19th January – Sunday 3rd March 2019 Temporary Exhibition Gallery A look back at the days of steam through the eyes of artist and railway enthusiast Stephen Bainbridge. Normal entrance fee. The Afternoon Lectures: Saturday 9th February 2019 at 1.45pm Meeting Room ‘North Yorkshire Moors Railway’ – A talk by Philip Benham Philip Benham the former Managing Director of the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, the UK’s largest steam line will talk about the history and development of the railway. -

RT Rondelle PDF Specimen

RAZZIATYPE RT Rondelle RAZZIATYPE RT RONDELLE FAMILY Thin Rondelle Thin Italic Rondelle Extralight Rondelle Extralight Italic Rondelle Light Rondelle Light Italic Rondelle Book Rondelle Book Italic Rondelle Regular Rondelle Regular Italic Rondelle Medium Rondelle Medium Italic Rondelle Bold Rondelle Bold Italic Rondelle Black Rondelle Black Italic Rondelle RAZZIATYPE TYPEFACE INFORMATION About RT Rondelle is the result of an exploration into public transport signage typefa- ces. While building on this foundation it incorporates the distinctive characteri- stics of a highly specialized genre to become a versatile grotesque family with a balanced geometrical touch. RT Rondelle embarks on a new life of its own, lea- ving behind the restrictions of its heritage to form a consistent and independent type family. Suited for a wide range of applications www.rt-rondelle.com Supported languages Afrikaans, Albanian, Basque, Bosnian, Breton, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Faroese, Fijian, Finnish, Flemish, French, Frisian, German, Greenlandic, Hawaiian, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Irish, Italian, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Maltese, Maori, Moldavian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Provençal, Romanian, Romany, Sámi (Inari), Sámi (Luli), Sámi (Northern), Sámi (Southern), Samoan, Scottish Gaelic, Slovak, Slovenian, Sorbian, Spa- nish, Swahili, Swedish, Tagalog, Turkish, Welsh File formats Desktop: OTF Web: WOFF2, WOFF App: OTF Available licenses Desktop license Web license App license Further licensing -

Royal Newcastle Infirmary

Accounting for Healthcare in the Newcastle Infirmary During the 19th Century Andrew John Holden Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University Business School June 2018 i To Gill, Olly and Emily for all your support, encouragement and love ii Newcastle Infirmary c 1815 Figure 0.1 – The Newcastle Infirmary (Source: Welcome Library Images) To serve the needy, sick and lame, This splendid shilling freely came, From one who knows the want of wealth, And what is more - the want of health. Beneath this roof may thousands find, The greatest blessings of mankind; And hence may millions learn to know, That to do good’s our end below; That Vice and Folly must decay Ere we can reach eternal day! (Anon. Above poem written on a note which enclosed a shilling left in a poor box 1752 – from Hume 1951, p. 5) iii Abstract Accounting played a critical role in the management of the Newcastle Infirmary during the 19th century. In a class-based society, the poor relied upon the generosity of the wealthy for their healthcare at a time when poverty itself was seen as a sin, an act against God. These wealthy donors established and maintained hospitals, such as the Newcastle Infirmary, and were responsible for the governance, management and admission of patients. Their aim was to be seen to use resources efficiently and to treat the “deserving poor” to restore them to productive members of society. Throughout the century new buildings, medical advances and increasingly highly specialised staff had to be financed to cope with increasing demand.