Download the Full Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Trade USA® Works of Many Leading the with Brands And

• FAIR TRADE USA • Fair Trade USA® CAPITAL CAMPAIGN FINAL REPORT 1 It started with a dream. What Visionary entrepreneur and philanthropist Bob Stiller and his wife Christine gave us a if our fair trade model could It Started spectacular kick-off with their $10 million reach and empower even more matching leadership gift. This singular people? What if we could impact gift inspired many more philanthropists with a and foundations to invest in the dream, not just smallholder farmers giving us the chance to innovate and and members of farming expand. Soon, we were certifying apparel Dream and home goods, seafood, and a wider cooperatives but also workers range of fresh produce, including fruits on large commercial farms and and vegetables grown on US farms – something that had never been done in the in factories? How about the history of fair trade. fishers? And what about farmers • FAIR TRADE USA • In short, the visionary generosity of our and workers in the US? How community fueled an evolution of our could we expand our movement, model of change that is now ensuring safer working conditions, better wages, and implement a more inclusive more sustainable livelihoods for farmers, philosophy and accelerate the workers and their families, all while protecting the environment. journey toward our vision of Fair In December 2018, after five years and Trade for All? hundreds of gifts, we hit our Capital • FAIR TRADE USA • That was the beginning of the Fair Trade Campaign goal of raising $25 million! USA® Capital Campaign. • FAIR TRADE USA • This report celebrates that accomplishment, The silent phase of the Capital Campaign honors those who made it happen, and started in 2013 when our board, leadership shares the profound impact that this team and close allies began discussing “change capital” has had for so many strategies for dramatically expanding families and communities around the world. -

Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement

SEED WORKING PAPER No. 30 Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement by Andy Redfern and Paul Snedker InFocus Programme on Boosting Employment through Small EnterprisE Development Job Creation and Enterprise Department International Labour Office · Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2002 First published 2002 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; e-mail: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; e-mail: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement Geneva, International Labour Office, 2002 ISBN 92-2-113453-9 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Fair Trade 1 Fair Trade

Fair trade 1 Fair trade For other uses, see Fair trade (disambiguation). Part of the Politics series on Progressivism Ideas • Idea of Progress • Scientific progress • Social progress • Economic development • Technological change • Linear history History • Enlightenment • Industrial revolution • Modernity • Politics portal • v • t [1] • e Fair trade is an organized social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries to make better trading conditions and promote sustainability. It advocates the payment of a higher price to exporters as well as higher social and environmental standards. It focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine,[2] fresh fruit, chocolate, flowers, and gold.[3] Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect that seek greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[4] There are several recognized Fairtrade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO/Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing -

Fair Trade : Market-Driven Ethical Consumption

Fair Trade Market-Driven Ethical Consumption Alex Nicholls & Charlotte Opal eBook covers_pj orange.indd 86 21/4/08 15:34:02 Nicholls Prelims.qxd 5/9/2005 12:21 PM Page i FAIR TRADE Nicholls Prelims.qxd 5/9/2005 12:21 PM Page ii Nicholls Prelims.qxd 5/9/2005 12:21 PM Page iii FAIR TRADE MARKET-DRIVEN ETHICAL CONSUMPTION Alex Nicholls and Charlotte Opal SAGE Publications London ●●Thousand Oaks New Delhi Nicholls Prelims.qxd 5/9/2005 12:21 PM Page iv © Alex Nicholls and Charlotte Opal, 2005 Chapter 5 © Whitni Thomas, 2005 First published 2004 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave Post Box 4109 New Delhi 110 017 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1 4129 0104 9 ISBN 1 4129 0105 7 (pbk) Library of Congress Control Number: 20041012345 Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd,Trowbridge,Wiltshire Printed on paper from sustainable resources Nicholls Prelims.qxd 5/9/2005 12:21 PM Page v Let us spread the fragrance of fairness across all aspects of life. -

Paying the Price for Cocoa

QUARTERLY RETURN 113 AUTUMN 2019 PAYING THE PRICE FOR COCOA A SWAHILI SHARING SPIRIT Swahili Imports works with artisans in 15 African countries. A BIG THANK YOU To our volunteers who helped us out at festivals this Summer. SATIPO & ASUNAFO Read the story behind your chocolate bar. ONLINE PORTAL THE IMPORTANCE OF While we are aware that many of you still prefer INCREASING paper communication, we are conscious of its environmental impact. For this reason, we INVESTMENT encourage people to manage their Share Account online if they can. As a result, over a third of As Shared Interest Society reaches 10,000 members are registered to use our online portal, Share Accounts, our organisation’s growth ‘Our Shared Interest.’ can be a source of pride in work well done. It ensures that our reach is greater as we By signing up online, you can view your latest and increase our assets and so our potential to previous statements, change selected personal influence events around the world. details, as well as investing further and making withdrawals. For security purposes, all online withdrawals will be made into your nominated Like most of us, I am not an economist bank account. If your Share Account has more by training, so my grasp of the practical than one signatory, any transactional requests workings of forces of supply and demand will need to be approved by all parties before is hazy. However, what struck me clearly being actioned. in my first meeting as a new Council YOU CAN NOW INVEST member this Summer, was the frustration Instead of receiving your quarterly statement and that exists when the organisation does not WELCOME newsletter in the post, you will receive an email have enough money to satisfy need. -

The Case of Fair Trade

1 Evolution of non-technical standards: The case of Fair Trade Nadine Arnold1 Department of Sociology, University of Lucerne, Switzerland; email: [email protected] 2014 To cite this paper, a final version has been published as: Arnold Nadine (2014) Evolution of non-technical standards: The case of Fair Trade. In Francois-Xavier de Vaujany, Nathalie Mitev, Pierre Laniray and Emanuelle Vaast (Eds.), Materiality and Time. Organizations, Artefacts and Practices. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan (pp. 59-78). 2 Evolution of non-technical standards: The case of Fair Trade Nadine Arnold Abstract This contribution suggests examining non-technical standards as artefacts that evolve in accordance with their contextual setting. In the past, organization scholars have increasingly paid attention to standards and standardisation but they tended to ignore material aspects of the phenomenon. An analysis of the Fair Trade standardisation system shows how its underlying rules changed from guiding criteria to escalating standards. Taking an evolutionary perspective I outline four major trends in the written standards and relate them to the history of Fair Trade. Detected modifications were either meant to legitimate the standardisation system through the content of standards or to enable legitimate standardisation practice. Overall the exuberant growth of non-technical standards leads to critical reflections on the future development of Fair Trade and its standards. Introduction Standards are to be found everywhere. Distinct social spheres such as agriculture, education, medicine and sports have become the subject of standardisation. Corresponding standards have evolved without the enforcement of the hierarchical authority of states and they ‘help regulate and calibrate social life by rendering the modern world equivalent across cultures, time, and geography’ (Timmermans and Epstein, 2010, p. -

Sustainable Trade – No Aid

October, 2020 Sustainable Trade – No Aid Sustainable Global Value Chain Management in the Cacao Industry · taking a Collaborative Approach Anna Verbrugge Master’s Thesis for the Environment and Society Studies programme Nijmegen School of Management Radboud University If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together – African saying (Mout, 2019) i Colophon Document title: Sustainable Global Value Chain Management in the Cocoa Industry · taking a Collaborative Approach Project: Master thesis (MAN-MTHCS) Date: October 25, 2020 Word count: 30124 Version: Concept version Author: Anna Verbrugge Student number: 1039167 Education: MSc Environment and Society Studies, Radboud University Supervisor: Rikke Arnouts Second reader: S. Veenman ii Abstract This research aims to define what is missing in the current business approaches of chocolate companies that sustainability issues in the cocoa sector are commonplace. Despite the many initiatives of the companies and many billions of dollars spent by stakeholders to strengthen sustainability in the industry, real solutions seem a long way off. Chocolate companies seem busier with improving their own chains than with developing a holistic action plan to tackle the structural issues in the sector. To this end, this research examines what it is that makes a global value chain sustainable and how chocolate companies could drive sustainable change beyond their chains. By taking a collaborative approach, this research explores how a collaborative approach within and beyond the chains can help chocolate companies to scale up sustainability solutions and to make a greater sustainable impact in the sector as a whole. To explore the potential added value of a collaborative approach, a case study is conducted on three chocolate companies and sustainable pioneers in the cocoa industry: Tony’s Chocolonely, Divine Chocolate and Zotter. -

“When We Attend to the Needs of Those in Want, We Give Them What Is Theirs

! ! ! ! ! ! "When we attend to the needs of those in want, we give them what is theirs, not ours. More than performing works of mercy, we are paying a debt of justice.” Pope St. Gregory the Great! At one level, Fair Trade is a certification, making sure farmer and artisan cooperatives are meeting criteria. At another level it is our chance to live the Gospel message; to be truly “one body” with those who produce the food and goods we need and want. Fair Trade is about relationships. Being a follower of Jesus is also about relationships. We are in communion. CRS has a long-term relationship with 15 partners, which donate a percentage of all related sales back to CRS for their continued work. These partners are committed to Fair Trade to the point that they are donating profit to help disadvantaged farmers and artisans, and are helping us by making products available. ! The non-profit Divine Chocolate and Equal Peace Coffee and company, SERRV, is Exchange are the CRS Providence Coffee are the craft partner. They chocolate partners. Divine two of the CRS coffee have an awesome Chocolate is owned by its partners. Peace is in catalog and website. members, a truly unique Mpls. and Providence is Artisan cooperatives situation in the cocoa based in Faribault. Both are certified, which growing world. They also have websites and also means that each own nearly half of the market through parishes individual product may processing operation. and other local markets. not bear the Fair Equal Exchange also sells Peace Coffee can often Trade label. -

The Political Rationalities of Fair-Trade Consumption in the United Kingdom

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The political rationalities of fair-trade consumption in the United Kingdom Journal Item How to cite: Clarke, Nick; Barnett, Clive; Cloke, Paul and Malpass, Alice (2007). The political rationalities of fair-trade consumption in the United Kingdom. Politics and Society, 35(4) pp. 583–607. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] Version: [not recorded] Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1177/0032329207308178 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Title The political rationalities of fair trade consumption in the United Kingdom Authors Nick Clarke, Clive Barnett, Paul Cloke and Alice Malpass Authors’ contact details Nick Clarke, School of Geography, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, United Kingdom, tel. +44 (0)23 80 592215, fax +44 (0)23 80 593295, e-mail [email protected]. Clive Barnett, Faculty of Social Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, United Kingdom, tel. +44 (0)1908 654431, fax +44 (0)1908 654488, e-mail [email protected]. Paul Cloke, School of Geography, Archaeology, and Earth Resources, University of Exeter, The Queens Drive, Exeter, Devon, EX4 4QJ, United Kingdom, tel. +44 (0)1392 264522, fax +44 (0)1392 263342, e-mail [email protected]. -

F a I R T R a D E U

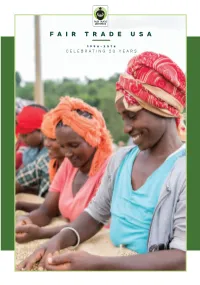

FAIR TRADE USA FAIR AL AL REPORT CELEBRATING 20 YEARS CELEBRATING 2018 ANNU 1998-2018 I AIR TRADE USA F I 1 DEAR FRIENDS, More than twenty years ago, an idealistic, young do-gooder (that would be me) brought an idea from Nicaragua to a one room office in Oakland, California. What started with coffee and conviction has grown into a global movement. Fair Trade USA is now the leading certifier of Fair Trade products in North America. There wouldn’t have been a one room Everyone did their part to make Fair office without the Ford Foundation Trade work, grow, and thrive. Fair Trade betting on us with our first grant. That USA simply wouldn’t have survived grant enabled conviction to become over 20 years or reached over 1 million confidence. families around the world without the everyday heroes who joined us to For Fair Trade USA to become challenge the status quo and re-imagine sustainable we needed more than capitalism. grant dollars. Early partners like Equal AL REPORT Exchange and Green Mountain Coffee We established Fair Trade USA as a signed on to the “crazy” notion of different kind of organization—a mission- buying Fair Trade Certified™ coffee and driven nonprofit that generates earned putting our seal on their products. These revenue and is financially sustainable. 2018 ANNU partnerships primed us to become a One that helps mainstream companies viable organization generating impact for combine sustainability and profitability. farmers worldwide. One that serves farmers, workers, I companies, consumers, and the earth, Our model would have collapsed without based on mutual benefit and shared those first consumers willing to buy Fair value. -

Fairtrade – a Competitive Imperative? an Investigation to Understand the Role of Fair Trade in Company Strategy in the Chocolate Industry

Fairtrade – a Competitive Imperative? An Investigation to Understand the Role of Fair Trade in Company Strategy in the Chocolate Industry Master’s Thesis in Business Administration Author: Phuong Thao Tran & Elina Vettersand Tutor: Anna Blombäck Jönköping University May 2012 Master’s Thesis in Business Administration Title: Fairtrade - a Competitive Imperative? Author: Phuong Thao Tran & Elina Vettersand Tutor: Anna Blombäck Date: 2012 -05-14 Subject terms: Strategic entrepreneurship, fair trade, competitive advantage. Abstract Background: The rise in ethical consumerism has become evident through an increase in sales of fair trade products in recent years. Consumers are prepared to pay a premium for fair trade chocolate, and with a steady future growth in the fair trade movement, this is an attractive market for new entrants. Of particular focus are the Swedish and German markets for fair trade chocolate as they show promising growth rates and interest in this field. Problem: The chocolate industry is very competitive, and the observation that con- sumers reward companies that act socially responsible presents an oppor- tunity for ethical companies to compete. This is attractive for entrepreneuri- al firms, but there exist numerous motivations why firms choose to engage in fair trade. Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to understand the role of fair trade in corpo- rate strategy (either in partial or entire assortment), its relation to entrepre- neurial opportunity-seeking behaviour, and examining how the strategic re- source of Fairtrade certification is used to gain competitive advantage. Method: A qualitative interview study was applied, and ten chocolate companies ac- tive in the Swedish and German markets were included in the sample. -

Assessing the Impact of Fairtrade Cocoa in Peru

08 Fall ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF FAIRTRADE FOR PERUVIAN COCOA FARMERS Karine Laroche, Roberto Jiménez, and Valerie Nelson June 2012 Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Abbreviations and Acknowledgements 4 List of boxes, tables and figures 5 1. Introduction 8 2. Methodology 8 Conceptual framework 8 Key steps in methodology 11 Sampling framework 12 Limitations 13 3. Context of cocoa trade 14 International market and trends 14 Organic cocoa market 20 Cocoa in Peru 20 Fairtrade market and trends 25 4. National and regional context 28 Economic context 28 Livelihood activities in San Martin 29 Socio-cultural characteristics of the area 29 Historical context 30 Structure and governance of the SPOs 31 Fairtrade and Fairtrade cocoa in Peru 33 5. Impact of Fairtrade on the social structure 33 Ability to participate in Fairtrade 33 Ability to benefit from Fairtrade 36 Gender issues 39 Farm labour 41 6. Impact of Fairtrade on the socio-economic situation of producers, workers and the 42 members of their households Producer prices 42 Profitability of production systems 46 Producer income stability and levels 49 Farmer livelihood assets and productive investments 52 Cash flow management 55 Stability of family farming 56 Household food security 58 7. Organization of producers 61 Structuring of the rural community 64 Use of the Fairtrade Premium 63 Influence on other producer organisations in the region 65 SPO capitalization and Fairtrade 66 SPO administrative and management capacities 68 Organizational business development 69 Quality 71 Diversification of products 72 Number and diversity of buyers 73 Negotiation, advocacy and networking capacity 77 Producer organization services 80 8.