A Puritan Bishop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

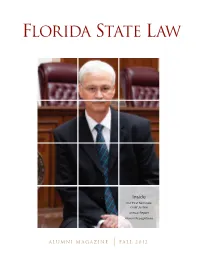

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 5 Article 2 March 2016 The urS prising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof John Leubsdorf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation John Leubsdorf, The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 1569 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leubsdorf: The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Pro THE SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE PREPONDERANCE STANDARD OF CIVIL PROOF John Leubsdorf * Abstract Although much has been written on the history of the requirement of proof of crimes beyond a reasonable doubt, this is the first study to probe the history of its civil counterpart, proof by a preponderance of the evidence. It turns out that the criminal standard did not diverge from a preexisting civil standard, but vice versa. Only in the late eighteenth century, after lawyers and judges began speaking of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, did references to the preponderance standard begin to appear. Moreover, U.S. judges did not start to instruct juries about the preponderance standard until the mid-nineteenth century, and English judges not until after that. The article explores these developments and their causes with the help of published trial transcripts and newspaper reports that have only recently become accessible. -

Come, Holy Ghost

Come, Holy Ghost John Cosin and 17th Century Anglicanism Notes from sabbatical study leave, Summer 2016 Donald Allister Come, Holy Ghost Sabbatical study Copyright © Donald Allister 2017 2 Come, Holy Ghost Sabbatical study Contents Come, Holy Ghost 4 Personal Interest 5 The Legacy of the 16th Century 8 Arminianism and the Durham House Group 10 The Origins of the Civil War 13 Cosin’s Collection of Private Devotions 14 Controversy, Cambridge, Catastrophe 16 Exile, Roman Catholicism, and the Huguenots 18 Breda, Savoy, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Act of Uniformity 22 Cosin’s Other Distinctive Views 25 Reflections 26 Collects written by Cosin and included in the 1662 Prayer Book 29 Cosin’s Last Testament 30 Some key dates 33 Bibliography 35 3 Come, Holy Ghost Sabbatical study Come, Holy Ghost, our souls inspire, and lighten with celestial fire. Thou the anointing Spirit art, who dost thy sevenfold gifts impart. Thy blessed unction from above is comfort, life, and fire of love. Enable with perpetual light the dullness of our blinded sight. Anoint and cheer our soiled face with the abundance of thy grace. Keep far from foes, give peace at home: where thou art guide, no ill can come. Teach us to know the Father, Son, and thee, of both, to be but One, that through the ages all along, this may be our endless song: Praise to thy eternal merit, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.1 Original Latin ascribed to Rabanus Maurus (died AD 856), traditionally sung at Pentecost, Confirmations, and Ordinations: Veni, creator Spiritus, / mentes tuorum visita, / imple superna gratia, / quae tu creasti, pectora. -

The 1641 Lords' Subcommittee on Religious Innovation

A “Theological Junto”: the 1641 Lords’ subcommittee on religious innovation Introduction During the spring of 1641, a series of meetings took place at Westminster, between a handful of prominent Puritan ministers and several of their Conformist counterparts. Officially, these men were merely acting as theological advisers to a House of Lords committee: but both the significance, and the missed potential, of their meetings was recognised by contemporary commentators and has been underlined in recent scholarship. Writing in 1655, Thomas Fuller suggested that “the moderation and mutual compliance of these divines might have produced much good if not interrupted.” Their suggestions for reform “might, under God, have been a means, not only to have checked, but choked our civil war in the infancy thereof.”1 A Conformist member of the sub-committee agreed with him. In his biography of John Williams, completed in 1658, but only published in 1693, John Hacket claimed that, during these meetings, “peace came... near to the birth.”2 Peter Heylyn was more critical of the sub-committee, in his biography of William Laud, published in 1671; but even he was quite clear about it importance. He wrote: Some hoped for a great Reformation to be prepared by them, and settled by the grand committee both in doctrine and discipline, and others as much feared (the affections of the men considered) that doctrinal Calvinism being once settled, more alterations would be made in the public liturgy... till it was brought more near the form of Gallic churches, after the platform of Geneva.3 A number of Non-conformists also looked back on the sub-committee as a missed opportunity. -

Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church Of

1 Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church of England in Restoration England, 1660-1688 David Kearns Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. David Kearns 29/06/2019 3 Authorship Attribution Statement This thesis contains material published in David Kearns, ‘Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675)’, Law and History Review, 37:2 (2019), 397-429, and material to be published in David Kearns and Ryan Walter, ‘Office, Political Theory, and the Political Theorist’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming). The research for these articles was undertaken as part of the research for this thesis. I am the sole author of the first article and sole author of section I of the co-authored article, and it is the research underpinning section I that appears in the thesis. David Kearns 29/06/2019 As supervisor for the candidature upon which this thesis is based, I can confirm that the authorship attribution statements above are correct. Andrew Fitzmaurice 29/06/2019 4 Acknowledgements Many debts have been incurred in the writing of this thesis, and these acknowledgements must necessarily be a poor repayment for the assistance that has made it possible. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974 Spinks, Bryan D. How to cite: Spinks, Bryan D. (1978) The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9577/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 BRYAN D. SPINKS THE EUCHARISTIC LITURGY. IN THE ENGLISH INDEPENDENT. OR CONGREGATIONAL,. TRADITION: A STUDY OF ITS CHANGING- STRUCTURE AND CONTENT 1550 - 1974 B.D.-THESIS 1978' The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Chapter .17 of this thesis is based upon part of an unpublished essay 1 The 1'apact of the Liturgical Movement on ii'ucharistic Liturgy of too Congregational Church in Jiu gland and Wales ', successfully presented for the degree of Master of Theology of the University of London, 1972. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

John Sadler (1615-1674) Religion, Common Law, and Reason in Early Modern England

THE PETER TOMASSI ESSAY john sadler (1615-1674) religion, common law, and reason in early modern england pranav kumar jain, university of chicago (2015) major problems. First, religion—the pivotal force I. INTRODUCTION: RE-THINKING EARLY that shaped nearly every aspect of life in seventeenth- MODERN COMMON LAW century England—has received very little attention in ost histories of Early Modern English most accounts of common law. As I will show in the common law focus on a very specific set next section, either religion is not mentioned at all of individuals, namely Justices Edward or treated as parallel to common law. In other words, MCoke and Matthew Hale, Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Henry historians have generally assumed a disconnect Finch, Sir John Doddridge, and-very recently-John between religion and common law during this Selden.i The focus is partly explained by the immense period. Even works that have attempted to examine influence most of these individuals exercised upon the intersection of religion and common law have the study and practice of common law during the argued that the two generally existed in harmony seventeenth century.ii Moreover, according to J.W. or even as allies in service to political motives. Tubbs, such a focus is unavoidable because a great The possibility of tensions between religion and majority of common lawyers left no record of their common law has not been considered at all. Second, thoughts.1 It is my contention that Tubbs’ view is most historians have failed to consider emerging unwarranted. Even if it is impossible to reconstruct alternative ways in which seventeenth-century the thoughts of a vast majority of common lawyers, common lawyers conceptualized the idea of reason there is no reason to limit our studies of common as a foundational pillar of English common law. -

Anglican Worship and Sacramental Theology 1

The Beauty of Holiness: Anglican Worship and Sacramental Theology 1 THE CONGRESS OF TRADITIONAL ANGLICANS June 1–4, 2011 - Victoria, BC, Canada An Address by The Reverend Canon Kenneth Gunn-Walberg, Ph.D. Rector of St. Mary’s, Wilmington, Delaware After Morning Prayer Friday in Ascensiontide, June 3, 2011 THE BEAUTY OF HOLINESS: ANGLICAN WORSHIP AND SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY When I was approached by Fr. Sinclair to make this presentation, he suggested that the conceptual framework of the lectures would be that they be positive presentations of traditional Anglican principles from both a biblical and historical perspective and in the light of the contemporary issues in contrast to traditional Anglicanism, especially as expressed in the Affirmation of St. Louis and in the 39 Articles. The rubrics attached to this paper were that Anglican worship should be examined in the light of contemporary liturgies, the Roman Rite, and the proposed revision of the Book of Common Prayer to bring it in line with Roman views. This perforce is a rather tall order; so let us begin. The late Pulitzer Prize winning poet W.H. Auden stated that the Episcopal Church “seems to have gone stark raving mad…And why? The Roman Catholics have had to start from scratch, and as any of them with a feeling for language will admit, they have made a cacophonous horror of the mass. Whereas we had the extraordinary good fortune in that our Prayer Book was composed at exactly the right historical moment. The English language had become more or less what it is today…but the ecclesiastics of the 16 th century still professed a feeling for the ritual and ceremonies which today we have almost entirely lost.” 1 While one might quibble somewhat with what he said, he certainly would have been more indignant had he witnessed me little more than a decade after his death celebrating the Eucharist before the Dean and Canons of St. -

2018 Table of Contents I. Articles

AALS Law and Religion Section Annual Bibliography: 2018 Table of Contents I. Journal Articles ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Special Journal Issues ............................................................................................................................................ 7 III. Monographs ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Edited Volumes ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Articles Zoe Adams & John Olusegun Adenitire, Ideological Neutrality in the Workplace, 81 MODERN L. REV. 348 (2018) Ryan T. Anderson, A Brave New World of Transgender Policy, 41 HARV. J. L. & PUBLIC POLICY 309 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Kuteh v. Dartfod and Gravesham NHS Trust, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 113 (2018) Ruth Arlow, The Reverend J. Gould v. Trustees of St. John’s, Downshire Hill, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 241 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Scott v. Stevenson & Reid Ltd: Northern Ireland Fair Employment Tribunal, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 245 (2018) Giorgia Baldi, Re-conceptualizing Equality in the Work Place: A Reading of the Latest CJEU’s Opinions over the Practice of Veiling, 7 OXFORD J. L. & RELIG. 296 (2018) Luke Beck, The Role of Religion in the Law of Royal Succession in Canada and -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement.