News Release(研究成果情報) 氷

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distinct Herpesvirus Resistances and Immune Responses of Three

Gao et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:561 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-3945-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distinct herpesvirus resistances and immune responses of three gynogenetic clones of gibel carp revealed by comprehensive transcriptomes Fan-Xiang Gao1,2, Yang Wang1, Qi-Ya Zhang1, Cheng-Yan Mou1,2, Zhi Li1, Yuan-Sheng Deng1,2, Li Zhou1* and Jian-Fang Gui1* Abstract Background: Gibel carp is an important aquaculture species in China, and a herpesvirus, called as Carassius auratus herpesvirus (CaHV), has hampered the aquaculture development. Diverse gynogenetic clones of gibel carp have been identified or created, and some of them have been used as aquaculture varieties, but their resistances to herpesvirus and the underlying mechanism remain unknown. Results: To reveal their susceptibility differences, we firstly performed herpesvirus challenge experiments in three gynogenetic clones of gibel carp, including the leading variety clone A+, candidate variety clone F and wild clone H. Three clones showed distinct resistances to CaHV. Moreover, 8772, 8679 and 10,982 differentially expressed unigenes (DEUs) were identified from comparative transcriptomes between diseased individuals and control individuals of clone A+, F and H, respectively. Comprehensive analysis of the shared DEUs in all three clones displayed common defense pathways to the herpesvirus infection, activating IFN system and suppressing complements. KEGG pathway analysis of specifically changed DEUs in respective clones revealed distinct immune responses to the herpesvirus infection. The DEU numbers identified from clone H in KEGG immune-related pathways, such as “chemokine signaling pathway”, “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway” and others, were remarkably much more than those from clone A+ and F. -

Chapter 2 Healthy Interaction Between Human and the Earth

FY2010 Part 1, Chapter 2 -Healthy Interaction between Human and the Earth Chapter 2 Healthy Interaction between Human and the Earth As seen in Chapter 1, we humans depend on under- which remained until today heavily depend on them ground resources such as fossil fuels and minerals, as (Figure 2-1-1). well as renewable resources such as food, forest and In Chapter 2, we will consider about how to achieve water. These natural resources provide energy, food, the wisdom in order to assist local everyday lives timber, medicine and so on, which are vital for human which based on traditional knowledge, to maintain the beings. We also depend on the fundamental roles of relationship in good condition between human beings and ecosystems; healthy forests, for example, regulate the Earth’s environment and to share the benefits of damages from heavy rainfall caused by typhoons. These ecosystem services with the future generation, focusing natural resources and ecosystems support various on status of renewable resources of biodiversity. patterns of human life styles, and indigenous cultures Section 1 Benefits of Ecosystem Services on the Earth for Our Everyday Lives There are 1.75 million identified species. Including Here, we will discuss the relationship between our unknown living organisms, it is said that there are 30 everyday lives and ecosystem services of biodiversity, million species on the Earth. Humans are nothing more mainly from the perspective of how ecosystem services than one of the many species, and it would be impossible provide security in everyday life, timbers for building, for us humans to exist without interrelationship with food, medicine for our health, and traditional cultures in these innumerable living organisms. -

Ecological Notes of the Fishes and the Interspecific Relations Among Them in Lake Biwa

Ecological Notes of the Fishes and the Interspecific Relations among Them in Lake Biwa Taizo MIURA Introduction Lake Biwa has been much interested by biologists, specially by ichthiologists because of the richness and variety of the lake fish fauna and of their diverse origin. Therefore, a good number of papers on taxonomic researches of the fishes have been published. However ecological studies of the fishes have been poorly made. Freshwater environments as well as terrestrial ones have been practically reformed, accompanied with development of human society and specially of industries and agriculture. Lake Biwa is also not an exception. Recently the ministry of construction is planning to construct a dam between the north basin and the south basin of the lake, and to pump up water from the north basin to the south one for the purpose of holding a continuous water supply to the outlet river. By such programme the two basins will nearly be disconnected and the water level of the north basin is often expected to be lowered. It can be easily expected that production of the organisms in the lake will be affected by the reformation, so that it 'is important to predict how the organic production will be affected, and to propose how the programme should be made in order to benefit the local people, especially the fishermen. Thus, about sixty scientists including biologists, physicists, chemists and agricultural economists had formed a co-operative research team and have investigated the biotic re- sources of the lake from 1962 to 1965. Through this investigation ecological studies of some of the fish species have been intensively made. -

Lake Biwa Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

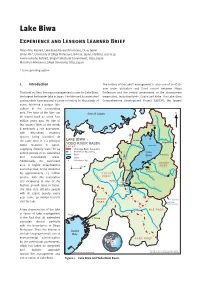

Lake Biwa Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Tatuo Kira, Retired, Lake Biwa Research Institute, Otsu, Japan Shinji Ide*, University of Shiga Prefecture, Hikone, Japan, [email protected] Fumio Fukada, Retired, Shiga Prefectural Government, Otsu, Japan Masahisa Nakamura, Shiga University, Otsu, Japan * Corresponding author 1. Introduction The history of the lake’s management is also one of confl icts over water utilization and fl ood control between Shiga This brief outlines the major management issues for Lake Biwa, Prefecture and the central government or the downstream the largest freshwater lake in Japan. The lake and its watershed mega-cities, including Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe. The Lake Biwa communities have enjoyed a common history for thousands of Comprehensive Development Project (LBCDP), the largest years, fostering a unique lake culture in the surrounding area. The birth of the lake can 6HDRI-DSDQ 1 be traced back to some four million years ago. As one of few ancient lakes in the world, /<RJR it embraces a rich ecosystem, with fi fty-seven endemic species being recorded. At DNDWRNL5 7 $QH5 the same time, it is a principal /$.(%,:$ ,PD]X <2'25,9(5%$6,1 1DJDKDPD water resource in Japan, $GR5 1RUWK%DVLQ -$3$1 supplying drinking water for 14 'UDLQDJH%DVLQ%RXQGDU\ million people in its watershed 3UHIHFWXUH%RXQGDU\ /DNH 5LYHU %LZD +LNRQH and downstream areas. /DNH Additionally, its catchment 6HOHFWHG&LW\ 6+,*$ area is highly industrialized NP 35() and urbanized, being inhabited .DWDWD 2PL +DFKLPDQ (FKL5 by approximately 1.3 million . .<272 DWVXUD5 +LQR5 people, with the population 35() ,/(& still increasing at one of the .\RWR 6RXWK%DVLQ 2WVX .XVDWVX highest growth rates in Japan. -

Difference in the Hypoxia Tolerance of the Round Crucian Carp and Largemouth Bass: Implications for Physiological Refugia in the Macrophyte Zone

Short Report Difference in the hypoxia tolerance of the round crucian carp and largemouth bass: implications for physiological refugia in the macrophyte zone Hiroki Yamanaka1**, Yukihiro Kohmatsu2, and Masahide Yuma3 1 Center for Ecological Research, Kyoto University, 2-509-3 Hirano, Otsu, Shiga 520-2113, Japan 2 Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 457-4 Motoyama, Kamigamo, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan 3 Department of Environmental Solution Technology, Faculty of Science & Technology, Ryukoku University, 1-5 Seta-Oe, Otsu, Shiga 520-2194, Japan * Present address: Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), 457-4 Motoyama, Kamigamo, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan (e-mail: [email protected]) Received: August 28, 2006 / Revised: November 28, 2006 / Accepted: December 1, 2006 Abstract The hypoxia tolerance of larval and juvenile round crucian carp, Carassius auratus gran- Ichthyological doculis, and largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, was determined using respirometry to examine the potential of hypoxic areas in the macrophyte zone as physiological refugia for round crucian carp. Research The tolerance, which was measured as the critical oxygen concentration (Pc), was 1.32 mg O /l in the ©The Ichthyological Society of Japan 2007 2 round crucian carp and 1.93 mg O2/l in the largemouth bass. As the round crucian carp tolerated Ichthyol Res (2007) 54: 308–312 hypoxia better than the largemouth bass, hypoxic areas in the macrophyte zone might function as physiological refugia for round crucian carp. DOI 10.1007/s10228-006-0400-0 Key words Hypoxia tolerance · Critical oxygen concentration (Pc) · Physiological refugia · Carassius auratus grandoculis · Micropterus salmoides or many larval and juvenile fi shes, the macrophyte early life history (Miura, 1966; Yuma et al., 1998). -

Development of Sense Organs and Mouth and Feeding of Reared Marble Goby Oxyeleotris Marmoratus Larvae*

Fisheries Science 60(4), 361-368 (1994) Development of Sense Organs and Mouth and Feeding of Reared Marble Goby Oxyeleotris marmoratus Larvae* Shigeharu Senoo,*1 Kok Jee Ang,*1 and Gunzo Kawamura*2 *1 Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science , Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, 43400 UPM, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia *2Faculty of Fisheries , Kagashima University, Shimoarata, Kagoshima 890, Japan (Received August 23, 1993) To obtain the fundamental information required toooestablish an artificial seed production technique for the marble goby Oxyeleotris marmoratus, the development of sense organs and mouth and the feeding of the larvae were observed. The larvae exhibited a S-posture and horizontal swimming at 2 days after fertilization (d AF) and commenced feeding on phytoplankton (species unknown) at 3 d AF when the eyes, the otic vesicle with ciliated epithelium, the free neuromasts on the head and the trunk, and the ciliated olfactory epithelium were functional. The first taste buds appeared in the oral cavity at 6 d AF after the onset of feeding on Brachinous spp. The larvae commenced feeding on Cyclops sp. at 7 d AF, Moina sp. at 10 d AF, and Anemia salina nauplii at 15 d AF. This change of feeding might be due to the development of the mouth and mobility of larvae rather than the development of sense organs. At 20 d AF, the larvae developed free neuromasts on the caudal fin. Twin cones and rods appeared in the ratinae at 30 d AF when the larvae changed in phototaxis from positive to negative. The larvae became benthic in habit at 35 d AF. -

Predation by Crucian Carp Larva/Fry Visualizes Biological Interactions of Paddy Field Community

Predation by crucian carp larva/fry visualizes biological interactions of paddy field community Taisuke Ohtsuka & Shigehumi Kanao Introduction Carassius auratus grandoculis (nigorobuna in Jap- anese) is a crucian carp endemic to Lake Biwa, and it is used as an ingredient in Funa-zushi (lac- to-fermented fish) that has been the specialty food of Shiga prefecture, Japan. In recent years, however, its catch has declined drastically. The increase in carnivorous fishes intro- duced from North America (Micropterus salmoides and Lepomis macrochirus), reed community decline, and artificial water level regulation are possible causes of the marked decline. Because it can also reproduce in paddy fields, About 30 days old juveniles of Carassius au- breeding their larvae/fry in the paddies have been ratus grandoculis grown in a paddy field. carried out with the aim of reviving the stock. Two More than five times in length, and 500 times in weight of the newly hatched larva. ways of breeding are now conducted. One is stock- ing larvae in paddies, and another is constructing 15-44 days of age in body weight. This retardation fish pass from drainage to paddies for the run of of growth suggests deficient of preferable foods (see their adults. below). Ejecting juveniles to the drainage connect- We conducted some experiments to confirm ing to Lake Biwa in time with mid-season drainage the function of paddies as a nursery of the carp, and (usually about 40 days after transplanting of rice those to examine the impact of the larvae/fry stock- plant) is, therefore, appropriate for their stock en- ing on the paddy field ecosystem (Kanao et al. -

Multiyear Use for Spawning Sites by Crucian Carp in Lake Biwa, Japan

Journal of Advanced Marine Science and Technology Society, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 19–30, 2018 Original Paper Multiyear use for spawning sites by crucian carp in Lake Biwa, Japan Yoshio Kunimune*1, Yasushi Mitsunaga*2 *1 Graduate School of Agriculture, Kindai University, 3327-204 Naka-machi, Nara, Nara, 631-8505, Japan *2 Faculty of Agriculture, Kindai University, 3327-204 Naka-machi, Nara, Nara, 631-8505, Japan, [email protected] Received: July, 10. 2018, Accepted: October, 19. 2018 Abstract From April 2008 to July 2009, an acoustic telemetry study on crucian carp was conducted in Lake Biwa, Japan. Twenty Nigorobuna, ten gengoroubuna and one ginbuna captured during spawning seasons were released with ultrasonic transmitters in the South Basin. Signals from the tagged fish were detected by 28 ultrasonic-receiver stations installed around Lake Biwa. Seasonal preference of habitats was examined by distance-based analysis. Seasonal distributions of nigorobuna and gengoroubuna in Lake Biwa were observed including consecutive two spawning seasons. It was revealed that seasonal migration patterns of nigorobuna and gengoroubuna were different. Nigorobuna appeared mainly around the release site all the year round, while gengoroubuna migrated to the North Basin after their spawning season, where they stayed during the non-spawning season, and moved to the South Basin in the next midwinter, where they stayed until the end of the next spawning season. It was also revealed that gengoroubuna preferred lower water temperature than nigorobuna. Gengoroubuna moved faster than nigorobuna and ginbuna. There were high-degree correlations in distance ratios of each station during spawning seasons in the release year and the next year in both nigorobuna and gengoroubuna, suggesting a multiyear use for the same spawning site. -

Carassius Ve Střední Evropě

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Přírodovědecká fakulta Ivo PAPOUŠEK MOLEKULÁRNĚ-GENETICKÉ ANALÝZY DRUHŮ RODU CARASSIUS VE STŘEDNÍ EVROPĚ Přílohy k disertační práci Školitel: prof. RNDr. Jiřina Relichová, CSc. Školitel-specialista: RNDr. Věra Lusková, CSc. Brno, 2008 PŘÍLOHY – SOUBOR PUBLIKACÍ Příloha I Papoušek, I., Vetešník, L., Halačka, K., Lusková, V., Humpl, M. & Mendel, J. (2008). Identification of natural hybrids of gibel carp Carassius auratus gibelio (Bloch) and crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) from lower Dyje River floodplain (Czech Republic). Journal of Fish Biology 72, 1230-1235. Příloha II Vetešník, L., Papoušek, I., Halačka, K., Lusková, V. & Mendel, J. (2007). Morphometric and genetic analysis of Carassius auratus complex from an artificial wetland in Morava River floodplain, Czech Republic. Fisheries Science 73, 817-822. Příloha III Papoušek, I., Lusková, V., Halačka, K., Koščo, J., Vetešník, L., Lusk, S. & Mendel, J. (2008). Genetic diversity of the Carassius auratus complex (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) in the central Europe. Journal of Fish Biology (submitted 10/2008). Příloha I Papoušek, I., Vetešník, L., Halačka, K., Lusková, V., Humpl, M. & Mendel, J. (2008). Identification of natural hybrids of gibel carp Carassius auratus gibelio (Bloch) and crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) from lower Dyje River floodplain (Czech Republic). Journal of Fish Biology 72, 1230-1235. Journal of Fish Biology (2008) 72, 1230–1235 doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01783.x, available online at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com Identification of natural hybrids of gibel carp Carassius auratus gibelio (Bloch) and crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) from lower Dyje River floodplain (Czech Republic) I. PAPOUSˇEK*, L. VETESˇNI´K,K.HALACˇKA,V.LUSKOVA´,M.HUMPL AND J. -

In Lake Biwa

79 Countermeasures against Alien Fishes (Largemouth Bass and Bluegill) in Lake Biwa Atsuhiko IDE* and Shinsuke SEKI* Abstract Lake Biwa is one of the world's most ancient lakes, with an origin going back four million years. Many aquatic organisms, including more than 30 endemic species or subspecies of fish and molluscs inhabit the lake, and various kinds of fisheries have targeted those animals for centuries. Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) and largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) were first found in Lake Biwa in 1965 and 1974. While bluegill spread gradually through the shallow water zones and into small lagoons surrounding the lake, largemouth bass increased explosively in the 1980s. Simultaneously, native fishes such as crucian carp and bitterlings disappeared from the coastal shallows. After that, the population of bluegill began to increase. In recent years, bluegill has comprised over 90% of the fish fauna in Lake Biwa's south basin. Since 1985, fishermen have been trying continuously to reduce these alien species by several means. Fishing gear such as Eri (a set-net), gill nets, and pulling nets have been used. Recently, over 400 metric tons per year of these alien fishes have been eliminated. At the same time, the Shiga Prefectural Fisheries Experimental Station has tried to develop more effective gear to catch them. We have devised a pot trap, with its top covered by a sheet to provide shade, for efficient capture of the alien fishes, and a small beam trawl for use in beds of submerged aquatic vegetation. Other methods for the eradication of the alien fishes are currently under study. -

Japan March 2009

Fourth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity Japan March 2009 Chapter 1 Overview of Status, Trends, and Threat to Biodiversity 1. Biodiversity in Japan 1.1 Features of biodiversity in Japan 1.2 Status of threatened wildlife 1.2 Review of the Red List 2. Structure of the biodiversity crisis in Japan 2.1 First crisis (brought about by human activities and development) 2.2 Second crisis (brought about by reduced human activities) 2.3 Third crisis (brought about by artificially introduced factors) 2.4 Crisis brought about by global warming 3. Biodiversity in each geographical area 3.1 Natural mountain areas 3.2 Satochi-satoyama areas/countryside 3.3 Urban areas 3.4 River/wetland areas 3.5 Oceanic/coastal areas 3.6 Island areas Chapter 2 Status of National Biodiversity Strategy 1. National Biodiversity Strategy in Japan 1.1 The background of the formulation of the Third National Biodiversity Strategy 1.2 Structure and character of the Third National Biodiversity Strategy 1.3 Targets and Basic Policies for National Strategy (1) Three targets (2) Grand design for the National Land and the Centennial Plan (3) Five basic perspectives (4) Four basic strategies (5) 2010 Biodiversity Target and the National Biodiversity Strategy 1.4 Check and Review of the National Strategy 1.5 Basic Act on Biodiversity of Japan and the National Strategy 2. Implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy 2.1 Measures and policies for national land area (1) Ecological Network (2) Conservation of priority areas (3)Nature restoration (4)Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (5)Forests (6) Countryside and satochi-satoyama areas (7) Urban Areas (8) Rivers and wetlands (9) Coastal Areas and Oceanic Areas 2.2 Cross-sectional and fundamental measures (1) Protection and management of wildlife (2)Sustainable Use of Genetic Resources (3) Promotion and implementation (4) International Cooperation (5) Information management and technology development (6) Measures against global warming (7) Environmental Impact Assessment 3. -

UNIVERSITY of WISCONSIN-LA CROSSE Graduate Studies

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-LA CROSSE Graduate Studies VARIATION IN GILL RAKERS OF ASIAN CARP AND NATIVE FILTER-FEEDING FISHES FROM THE ILLINOIS, JAMES AND WABASH RIVERS, USA. A Manuscript Style Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Liza Walleser College of Science and Health Biology December, 2012 VARIATION IN GILL RAKERS OF ASIAN CARP AND NATIVE FILTER-FEEDING FISHES FROM THE ILLINOIS, JAMES AND WABASH RIVERS, USA. By Liza Walleser We recommend acceptance of this thesis in partial fulfillment of the candidate's requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology. The candidate has completed the oral defense of the thesis. Mark Sandheinrich, Ph.D. Date Thesis Committee Chairperson Jon Amberg, Ph.D. Date Thesis Committee Member David Howard, Ph.D. Date Thesis Committee Member Mark Gaikowski Date Thesis Committee Member Thesis accepted Robert H. Hoar, Ph.D. Date Associate Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs ii OFFICE OF UNIVERSITY GRADUATE STUDIES University of Wisconsin – La Crosse REVISION COMMUNICATION RECORD FORM NOTE: THIS FORM MUST BE COMPLETED AND SUBMITTED BY THE STUDENT WHEN A THESIS (OR OTHER CULMINATING PROJECT REPORT) IS SUBMITTED TO THE OFFICE OF UNIVERSITY GRADUATE STUDIES FOR EDITING AND APPROVAL Student’s Name: Liza Walleser Home Phone: (612) 554-4819 Complete Local Address: 2202 Jackson St Work/Temporary Phone: N/A City, State Zip: La Crosse, WI 54601 E-mail: [email protected] Academic Department: Biology Grad. Program: Master of Science Title of Thesis/Project: Variation in Gill Rakers of Asian Carp and Native Filter-Feeding Fishes from the Illinois, James and Wabash Rivers, USA.