Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Wildlife Attacks on Humans in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maxillofacial Bite Injuries Treatment – 20 Years Experience

Cent. Eur. J. Med. • 9(3) • 2014 • 461-467 DOI: 10.2478/s11536-013-0296-9 Central European Journal of Medicine Maxillofacial bite injuries treatment – 20 years experience Research Article Konstantinović S. Vitomir*1, Puzović Z. Dragana2 1 Clinic of Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, University of Belgrade,1 1000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 Institute of Forensic Medicine, School of Dentistry, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. Received 29 November 2012; Accepted 24 June 2013 Abstract: Management of bite injuries of the face is a part of everyday maxillofacial practice. The aim of the paper was to evaluate the bite injuries in the maxillo-facial region and to recommend treatment protocols. Materials and methods: The study was performed as a retrospective analysis of the medical records of University Clinic for maxillo-facial surgery in Belgrade. A total of 408 patients were treated for bite injuries of the maxillofacial region according to the same surgical protocol. Results: Animal bite injuries (92.9%) were much more common than human bites (7.1%). Dog bites (98.9%) were almost exclusive among animal bite injuries. Young males (58.7%), children and adolescents (44%) are predominately involved. The most frequently injured facial structure were lips (49.2%). Human bites presented in young males (86.2%), resulted from physical conflicts (58.6%) mostly affected cheeks (50%). Majority of injuries were Lackmann`s Class I and II. Conclusions: There were no reported infections or other complications after treatment with no need for secondary reconstruction. Factors that contribute to a good clinical outcome are: stage of the injury; short time interval from the injury to the admission into the hospital; no infection signs on admission; adequate surgical protocol with antibiotic prophylaxis. -

Year 4 Week 10 Reading Monday Read the End of the Story

Year 4 week 10 reading Monday Read the end of the story Read Ananse, the forgetful guest – Part 2. This is the end of the story we began on week 9. How does this ending compare with the ending that you predicted? Tuesday Watch the video clip about an Impala and a Leopard. Don’t be worried: it has a happy ending! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhSDxp0oQK8 Read some facts about leopards afterwards. www.bbc.co.uk/bigcat/animals/leopards/leopards.shtml Wednesday Read and find out facts about another cat such as a lion, tiger or a jaguar. Thursday Answer some questions Answer questions 1 to 5 about the video clip on the impala and the leopard. Think carefully about your answers. Write your answers as clear sentences. Friday Answer some questions Answer questions 6 to 9 about the video clip on the impala and the leopard. Think carefully about your answers. Write your answers as clear sentences. Year 4 week 10 reading Year 4 week 10 reading Year 4 week 10 reading Questions 1. Use a dictionary to find the meaning of the word ‘versatile’? Write the meaning that applies to the clip. 2. Why did the presenter say that leopards are the most versatile of all the big cats? 3. Why does the leopard need to slip pass the male puku without being seen? 4. Where did the leopard find cover for an ambush? 5. Why did the leopard attack the male puku? 6. According to the clip, how might the leopard succeed in finding its prey? 7. -

Human Attacks by Leopards in Uttarakhand, India: an Assessment Based on Perceptions of Affected People and Stakeholders

Human attacks by leopards in Uttarakhand, India: an assessment based on perceptions of affected people and stakeholders Study period: 2014-15 Date of report out: 6 April 2016 Project team: Sanjay Sondhi, Vidya Athreya, Anchal Sondhi, Arun Prasad, Amit Verma & Neha Verma Leopard image © Manoj Nair 1 of 35 Human attacks by leopards in Uttarakhand, India: an assessment based on perceptions of affected people and stakeholders Sanjay Sondhi1, Vidya Athreya3, Anchal Sondhi1, Arun Prasad1, Amit Verma2, Neha Verma2 1 Titli Trust, 49 Rajpur Road Enclave, Dhoran Khas, near IT Park, P.O. Gujrada, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, 248001, India. www.titlitrust.com. 2Uttarakhand Forest Department 3Wildlife Conservation Society - India. 1669, 31st cross, 16th main, Banashankari 2nd stage. Bangalore. 560070. India. Corresponding author: [email protected] Key words human wildlife conflict, Himalayas, Panthera pardus, social survey Abstract Attacks on humans by leopards have been a serious issue for many decades in Uttarakhand, India. This study uses forest department compensation data between 1998 and 2012 to ascertain conflict intensity in Uttarakhand and examines the social aspects of the conflict using on-the-ground assessment with affected victims, their families and associates of victims as well as other stakeholders such as forest department personnel, local community members, hunters and non-governmental organizations. A total of 80 interviews were conducted in 69 villages in five Forest Divisions of Pauri Garhwal, Tehri Garhwal, Almora, Lansdowne and Mussoorie. In addition 35 stakeholders were interviewed. Based on these interviews, the nature of leopard attacks on people, the landscape in which these attacks occurred, the seasons and times during which these attacks occurred were analyzed. -

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

The Role of Small Private Game Reserves in Leopard Panthera Pardus and Other Carnivore Conservation in South Africa

The role of small private game reserves in leopard Panthera pardus and other carnivore conservation in South Africa Tara J. Pirie Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Reading for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences November 2016 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors Professor Mark Fellowes and Dr Becky Thomas, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. I am sincerely grateful for their continued belief in the research and my ability and have appreciated all their guidance and support. I especially would like to thank Mark for accepting this project. I would like to acknowledge Will & Carol Fox, Alan, Lynsey & Ronnie Watson who invited me to join Ingwe Leopard Research and then aided and encouraged me to utilize the data for the PhD thesis. I would like to thank Andrew Harland for all his help and support for the research and bringing it to the attention of the University. I am very grateful to the directors of the Protecting African Wildlife Conservation Trust (PAWct) and On Track Safaris for their financial support and to the landowners and participants in the research for their acceptance of the research and assistance. I would also like to thank all the Ingwe Camera Club members; without their generosity this research would not have been possible to conduct and all the Ingwe Leopard Research volunteers and staff of Thaba Tholo Wilderness Reserve who helped to collect data and sort through countless images. To Becky Freeman, Joy Berry-Baker -

'Man-Eating·' Among Lions Panthera Leo with a Reconstruction of the Natural History of the 'Man-Eaters of Tsayo'

Journal of East African Natural History 90: 1-40 (2001) THE SCIENCE OF 'MAN-EATING·' AMONG LIONS PANTHERA LEO WITH A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE 'MAN-EATERS OF TSAYO' Julian C. Kerbis Peterhans University College, Roosevelt University 430 S. Michigan Ave. Chicago, IL, 60605-1394, U.S.A. & Division of Mammals, Field Museum of Natural History Chicago, IL, 60605-2496, U.S.A. jkerbis~frrn]h.org Thomas Patrick Gnoske Bird Division, Zoology Department, Field Museum of Natural History 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago 1160605-2496, U.S.A. tgnoske~frrn]h. org ABSTRACT The story of the 'Man-eaters of Tsavo' has been retold through script, cinema, and oral tradition in the 100+ years since their infamous 'reign of terror'. Despite their predictably broad popular appeal, the details pertaining to the natural history of these lions Panthera leo have never been reviewed. The skulls and skins of these lions have resided at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago) for over 75 years. An analysis of the skull of the primary culprit displays a traumatic injury that may have limited his predatory ability in subduing 'normal' prey. A sample of hairs, reflecting the diet of both man-eaters, is preserved in the broken and exposed cavities of their canines. Various additional circumstances likely contributed to their man-eating habit. The Tsavo incident closely followed the debut of rinderpest on the continent, which devastated cattle and buffalo, the primary prey of the Tsavo lion. The Tsavo 'nyika' consists of a dense thorn scrub thicket limiting visibility and passage, representing an ideal habitat for an 'ambush predator'. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet: The Impact of Tibetan Brown Bears and Other Wildlife on Nomadic Herders Dawa Tsering, John Farrington, and Kelsang Norbu August 2006 WWF China – Tibet Program Author Contact Information: Dawa Tsering, Tibet Academy of Social Sciences and WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] (+86)(891) 636-4380 John D. Farrington Tibet University 36 Jiangsu Road Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] [email protected] Kelsang Norbu WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet Abstract The multiple-use Chang Tang and Seling Lake Nature Reserves were created in 1993 to protect the unique assemblage of large fauna inhabiting the high-altitude steppe grasslands of northern Tibet, including the Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild ass, Tibetan brown bear, Tibetan Gazelle, wild yak, and snow leopard. Prior to creation of the reserve, many of these species were heavily hunted for meat and sale of parts. Since creation of the reserve, however, killing of wildlife by subsistence hunters and commercial poachers has declined while in the past five years a new problem has emerged, that of human-wildlife conflict. With human, livestock, and wildlife populations in the reserves all increasing, and animals apparently emboldened by reserve-wide hunting bans, all forms of human-wildlife conflict have surged rapidly since 2001. -

Proceedings of the First National Conference on Zoology

1 Biodiversity in a Changing World Proceedings of First National Conference on Zoology 28-30 November 2020 Published By Central Department of Zoology Institute of Science and Technology, Tribhuvan University Kathmandu, Nepal Supported By “Biodiversity in a Changing World” Proceedings of the First National Conference on Zoology 28–30 November 2020 ISBN: Published in 2021 © CDZ, TU Editors Laxman Khanal, PhD Bishnu Prasad Bhattarai, PhD Indra Prasad Subedi Jagan Nath Adhikari Published By Central Department of Zoology Institute of Science and Technology, Tribhuvan University Kathmandu, Nepal Webpage: www.cdztu.edu.np 3 Preface The Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University is delighted to publish a proceeding of the First National Conference on Zoology: Biodiversity in a Changing World. The conference was organized on the occasional of the 55 Anniversary of the Department from November 28–30, 2020 on a virtual platform by the Central Department of Zoology and its Alumni and was supported by the IUCN Nepal, National Trust for Nature Conservation, WWF Nepal and Zoological Society of London Nepal office. Faunal biodiversity is facing several threats of natural and human origin. These threats have brought widespread changes in species, ecosystem process, landscapes, and adversely affecting human health, agriculture and food security and energy security. These exists large knowledge base on fauna of Nepal. Initially, foreign scientist and researchers began explored faunal biodiversity of Nepal and thus significantly contributed knowledge base. But over the decades, many Nepali scientists and students have heavily researched on the faunal resources of Nepal. Collaboration and interaction between foreign researchers and Nepali researchers and students are important step for further research and conservation of Nepali fauna. -

Constrictor Snakes Attacks Factsheet

factsheet Texas Incidents Involving Dangerous Wild Animals Texas currently requires permits for, but does not ban big cats, bears, and some primate species. More children have been killed or injured by captive big cats in Texas than any other state, including a 3-year-old Lee County boy and 10-year-old Yorktown girl who were both killed by pet tigers and a Channelview 4-year-old who lost his arm and a 4-year-old Harris County girl who required $17,000 in plastic surgery after being mauled by big cats. Dozens of people have been injured by primates, including a teenager and an elderly woman who were both attacked by an escaped chimpanzee, a game warden who was bitten by one of several escaped pet rhesus macaque monkeys, and a pet Java macaque who sent a woman, a child, and a firefighter to the hospital after attacking and biting all three. Date Incident Location October 16, 2011 A 4-year-old boy was attacked and mauled by a 150-pound cougar who was kept as a pet Odessa, Texas by a relative. The child was standing near the cougar's cage when the animal reached out and grabbed him. The boy was taken to hospital with significant damage to the left side of his body. The cougar was seized by animal control officials and euthanized.1 October 14, 2011 One of five capuchin monkeys kept as pets escaped from a home and was on the loose Lake Hills, Texas for five days before being recaptured. The monkey reportedly attacked a dog and charged at a man, prompting three people to shoot at the animal.2,3 September 11, 2011 A game warden with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department was bitten by one of Plantersville, Texas several pet rhesus monkeys who were on the loose as a result of forced evacuations because of wildfires in the area. -

The Leopard Men of the Eastern Congo (Ca

The Leopard Men of the Eastern Congo (ca. 1890-1940): history and colonial representation Vicky L. M. Van Bockhaven This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of East Anglia, School of Art History and World Art Studies, Sainsbury Research Unit. December 2013 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract The research begins with a sculpture representing a “Leopard Man”, threatening to attack a sleeping victim, at the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Belgium. Recently this colonial icon was criticised for presenting a racist image. Leopard men killed on behalf of chiefs in the east of Congo (ca. 1890-1940). The emergence of a mythology of leopard men is analysed in relation to its suppression as an anti-colonial movement in the colony. This research highlights the distinctive potency of ethnographic objects as proof, shaping experiences of the colonised in the colonial museum, in relation to the text-focused study of the colonial discourse. The history of leopard men is reconstructed to break away from an exotic and de-historicised understanding. Two eastern Congolese varieties, anioto and vihokohoko, are studied, from which the RMCA display was derived. The micro- histories of conflict clusters are considered in the context of the Zanzibari slave trade and the Belgian colonisation as forms of empowerment. -

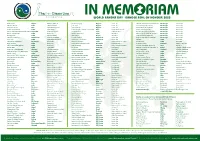

World Ranger Day I Ranger Roll of Honour 2020

WORLD RANGER DAY I RANGER ROLL OF HONOUR 2020 Alex Pajibo Liberia Death in Service Ibrahim Magaji Nigeria Homicide Héritier Ndagijimana Ndahobari DR Congo Homicide Hemant Kumar India Elephant attack John Paul Nigeria Homicide Lumumba Anuani Bihira DR Congo Homicide Shannon Barron USA Heart attack at work Simon Benku Nigeria Homicide Djamal Badi Mukandama DR Congo Homicide Sohan Singh Rawat India Tiger attack Gime Ángel Calderón Villasante Peru Heart attack at work Joseph Kasole Janvier DR Congo Homicide Maura Alejandra Hernandez Sierra Colombia Aneurism at work K. Mahendran India Elephant attack Agustin Mugisho Kulondwa DR Congo Homicide Bashir Ahmed Naik India Homicide Keshob Karmakar India Accident Jean-Louis Kambale Mutsomani DR Congo Homicide Annegowda India Elephant attack Alex Wayo Ghana Accident Jules Kambale Teremuka DR Congo Homicide Kanysh Nurtazinov Kazakhstan Killed by poachers Timothy Tembo Zimbabwe Homicide Ruphin Masumbuko Malekani DR Congo Homicide Kimo Miji India Japanese encephalitis Mabharani Chidhumo Zimbabwe Homicide Mahesh India Drowned François Kiwambisile DR Congo Homicide Sharmila Jayaram India Motor vehicle accident Shivakumar India Drowned Ajay Santosh India Drowning Maithree Wickramasinghe Sri Lanka Elephant attack Suparp Sinwan Thailand Death in service Rahul Damodhar Jadhav India Drowning Mat Kavanagh Australia Motor vehicle accident Cristian Gonzales Tanchiva Peru Covid 19 Bishan Ram India Tiger attack Bill Slade Australia Firefighting Damião Cristino de Carvahlo, Jr. Brazil Killed by illegal miners Suraiman Karemdamae Thailand Killed by poacher N’Serma Kataman Severin Benin Drowned Kan Chaiprasert Thailand Killed by poachers Mudiyanselage C K Basnayake Sri Lanka Elephant attack Elma Normandia Brazil Death in service Deepu Singh Rana India Killed by poachers Mamata Patil India Motor vehicle accident Lakhan Karmakar India Stroke while on duty Lathuram Bordoloi India Elephant attack Bienvenido ‘Toto’ Veguilla, Jr Philippines Killed by timber poachers Raúl Hernández Romero Mexico Homicide C. -

Fulla Taken to Udala Sub-Divisional Hos- 44 Age Group Will Soon Be Expanded Slot Bookings for Vaccination of 18-44 Rout, a Resident of Old Town Area

y k y cm LONG-DISTANCE RUNNER UK URGES COMMITMENT FEDERER OPTS OUT Actor Mrunal Thakur says that she has always British PM Boris will use G7 summit to urge world Roger Federer has pulled out of the taken projects which will help her survive leaders to commit to vaccinating the global French Open as he doesn’t want to longer in the industry LEISURE | P2 population by 2022 INTERNATIONAL | P10 pressurise his knees SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 67 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | MONDAY, JUNE 7 | 2021 12 PAGES | `5.00 VACCINE INEQUITY 9 pvt hosps corner 50% doses NINE CORPORATE HOSPITAL GROUPS CUMULATIVELY BOUGHT 60.57 LAKHS OF THE 1.20CR VACCINE DOSES IN MAY SINCE THE CENTRE REVISED ITS POLICY AND OPENED IT TO THE MARKET AGENCIES tion, the Supreme Court last Wednesday he nine private hospitals rapped the Centre on its vaccine pol- Fuel prices hiked again Mumbai, June 6: Reflecting the prob- Tare Apollo Hospitals; icy, calling the decision to make 18-44 Max Healthcare; Reliance lem of vaccine inequity, just nine cor- year olds pay for their doses “arbi- PRESS TRUST OF INDIA Foundation-run HN Hospital CITY FUEL PRICES (JUNE 6) porate hospital groups in big cities trary and irrational.” It asked the Trust; Medica Hospitals; Fortis PETROL `95.82 (+0.27) have cornered 50 per cent of the Covid- Healthcare; Godrej; Manipal Centre to review the vaccine policy New Delhi, June 6: Petrol IRREGULAR by MANJUL ` ` 19 vaccine stock meant for the private Health; Narayana Hrudalaya while observing that the digital divide price Sunday crossed 95 a DIESEL 93.72 (+0.32) sector in May.