Parody in the Chaldee Manuscript; Scott, Lockhart and an Unpublished Letter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepping Back to an Early Age: James Hogg's Three Perils of Woman and the Ion of Euripides David Groves

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 15 1986 Stepping Back to an Early Age: James Hogg's Three Perils of Woman and the Ion of Euripides David Groves Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Groves, David (1986) "Stepping Back to an Early Age: James Hogg's Three Perils of Woman and the Ion of Euripides," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 21: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol21/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. David Groves Stepping Back to an Early Age: James Hogg's Three Perils of Woman and the Ion of Euripides James Hogg's Three Perils of Woman; or. Love. Leasing. and Jealousy is a brilliant, searching, and enigmatic work which loosely but vividly re-casts Euripides' tragedy of 1011 in both nineteenth- and eighteenth-century Scotland. Written one year before Hogg's Confessions, The Three Perils of Woman is indebted to Ion for some aspects of plot and character, and follows Euripides in profoundly questioning the nature of divine justice by examining the sufferings of \\iomen. The novel presents questions, rather than answers, and so most of its 1823 reviewers were petrified by its "vulgarity" and its "shockingly irreverent" approach. Such a work was clearly unfit for women: one critic felt obliged to "make it a sealed book" for his wife and daughters, while another felt that Hogg's "occasional bursts of a higher strain" were unfortunately contaminated "with grosser passages, that must banish 'The three perils of Woman' from the toilets of those who would wish to learn what the perils are."l At first sight the work can be confusing in its division into overlapping volumes, "Perils," letters, and tales. -

Extempore Effusion’ •Janette Currie

ROMANTIC T EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1 7 8 0 – 1 8 4 0 (previously ‘Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text’) Issue 15 (Winter 2005) Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research Cardiff University Romantic Textualities is available on the web @ www.cf.ac.uk/encap/romtext ISSN 1748-0116 Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 15 (Winter 2005). Online: Internet (date accessed): <www.cf.ac.uk/encap/romtext/issues/rt15.pdf>. © 2006 Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research Published by the Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, Cardiff University. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro 11 / 12.5, using Adobe InDesign cs; images and illustrations prepared using Adobe Illustrator cs and Adobe PhotoShop cs; final output rendered with Ado- be Acrobat 6 Professional. Editor: Anthony Mandal, Cardiff University, UK. Reviews Editor: Tim Killick, Cardiff University, UK. Advisory Editors Peter Garside (Chair), University of Edinburgh, UK Jane Aaron, University of Glamorgan, UK Stephen Behrendt, University of Nebraska, USA Emma Clery, University of Southampton, UK Benjamin Colbert, University of Wolverhampton, UK Edward Copeland, Pomona College, USA Caroline Franklin, University of Swansea, UK Isobel Grundy, University of Alberta, Canada David Hewitt, University of Aberdeen, UK Gillian Hughes, University of Stirling, UK Claire Lamont, University of Newcastle, UK Robert Miles, University of Victoria, Canada Rainer Schöwerling, University of Paderborn, Germany Christopher Skelton-Foord, University of Durham, UK Kathryn Sutherland, University of Oxford, UK Aims and Scope: Formerly Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text (1997–2005), Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 is a twice-yearly journal that is commit- ted to foregrounding innovative Romantic-studies research into bibliography, book history, intertextuality, and textual studies. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Digging up the Kirkyard: Death, Readership and Nation in the Writings of the Blackwood’s Group 1817-1839. Sarah Sharp PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 2 I certify that this thesis has been composed by me, that the work is entirely my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Sarah Sharp 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Penny Fielding for her continued support and encouragement throughout this project. I am also grateful for the advice of my secondary supervisor Bob Irvine. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation for this project. Special thanks are due to my parents, Andrew and Kirsty Sharp, and to my primary sanity–checkers Mohamad Jahanfar and Phoebe Linton. -

Lockhart'smemoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 16 2012 WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mulderig, Gerald P. (2012) "WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 38: Iss. 1, 119–138. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol38/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART’S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig “[W]hat can the best character in any novel ever be, compared to a full- length of the reality of genius?” asked John Gibson Lockhart in his 1831 review of John Wilson Croker’s edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson.1 Like many of his contemporaries in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lockhart regarded Boswell’s dramatic recreation of domestic scenes as an intrusive and doubtfully appropriate advance in biographical method, but also like his contemporaries, he could not resist a biography that opened a window on what he described with Wordsworthian ardor as “that rare order of beings, the rarest, the most influential of all, whose mere genius entitles and enables them to act as great independent controlling powers upon the general tone of thought and feeling of their kind” (ibid.). -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street Douglas S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 23 2007 Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street Douglas S. Mack University of Stirling, Emeritus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mack, Douglas S. (2007) "Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 307–325. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/23 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Douglas S. Mack Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street For a' that, and a' that, Its comin yet for a' that, That Man to Man the warld o'er, Shall brothers be for a' that. Robert Burns Towards the end of January 1813 the young Edinburgh publisher George Goldie brought out a new book-length poem, The Queen's Wake. Somewhat unpromisingly, the book was by a little-known and impecunious former shep herd called James Hogg, whose recent attempts to launch a career, first as a farmer and later as a journalist, had ended in failure. Unexpectedly, the poem was very well received by reviewers and by the reading public, and by the au tumn of 1814 both fame and fortune appeared to be within the grasp of the author of The Queen's Wake. -

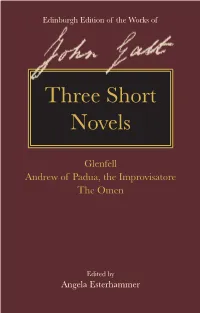

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

'Only Worthy Successor': the Career of James Hogg, 1801-1834

Conclusion The ‘Only Worthy Successor’: The Career of James Hogg, 1801-1834 1. The ‘Great Dead Poet’ and the ‘Gifted Living’: The Influence of Burns’s Poetic Legacy upon James Hogg In an article entitled ‘Some Observations on the Poetry of the Agricultural and that of the Pastoral District of Scotland, illustrated by a Comparative View of the Genius of Burns and the Ettrick Shepherd’ (printed in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in February 1819), John Wilson presents a ‘comparative view’ of Robert Burns and James Hogg that proved to be quite influential in the reception history of both poets. Viewing Burns as representative of ‘agricultural’ verse and Hogg of ‘pastoral’ due to their respective biographies, Wilson analy- ses the sources of their genius as expressed primarily in their writing. He contends that such an approach does not diminish their accomplishments, but merely highlights their particular differences as Scottish poets in their own ‘native dominions’: he writes, ‘There can be nothing more delightful than to see these two genuine children of Nature following the voice of her inspiration in such different haunts, each happy in his own native dominions, and powerful in his own legitimate rule’.1 This leads Wilson to remark upon the poets’ common class status, which is categorised as ‘peasant’. Of this unlikely source of distinction, Wilson observes that ‘most philosophical Englishmen acknowledge that there is a depth of moral and religious feeling in the peasantry of Scotland, not to be found among the best part of their population’ (309). Such linking of class and nation in the verse of Burns and Hogg leads Wilson to speculate upon the distinct character of the Scottish ‘peasantry’, a subject first addressed in the posthumous assessment of Burns by James Currie, his first editor.2 Wilson boldly asserts that ‘we do not feel any consciousness of national prejudice, when we say, that a great poet could not be born among the English peasantry’ (309). -

Margaret Oliphant: Gender, Identity, and Value in the Victonan Penodical Press

University of Alberta Margaret Oliphant: Gender, Identity, and Value in the Victonan Penodical Press Rhonda-Lea Carson-Batchelor O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Shidies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of English Edmonton, Alberta Fa11, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 ,mada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Senrices services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, ~e Weilington OttawaON KIAW Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Biblothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, Loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform., vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/lfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract The Victorian penod saw the rise of many women to professiond eminence in literary fields. Margaret Oliphant (1 828- l897), novelist, biographer, literary critic, social commentator, and historian, was just one who participated in the cultural debate about the changing place, role, and value of women within society and the workplace--'the woman questiony--buther conservative and careful feminism has attracted linle critical attention (or esteem) to her fiction. -

Obituary You Cannot Take Your Own When Travelling in a Strange Car

BRITISH AUG. 27, 1960 CORRESPONDENCE MEDICAL JOURNAL 671 and hats for themselves and for members of their fami- lies. I have bought five. One last point. As yet few cars have safety belts and Obituary you cannot take your own when travelling in a strange car. You can take your hat.-I am, etc., LORD HADEN-GUEST, M.C., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. The Institute of Orthopaedics, H. J. SEDDON, London, W.1. President, British Orthopaedic Lord Haden-Guest, who was a medical officer to one Association. of the earliest child-welfare clinics in London and then REFERENCE became a well-known Labour politician, died on Gissane, W., Brit. med. J., 1959, 1, 235. August 20. He was 83 years of age. Leslie Haden Guest was born at Oldham, Lancashire, on Cat Phobia March 10, 1877, the son of Dr. Alexander Haden Guest, SIR,-In your issue of August 13 (p. 497), writing of a who practised in Manchester and had many friends among case of cat phobia treated by them, Dr. H. L. Freeman the Fabians and radical thinkers of his day. Educated at and Mr. D. C. Kendrick are guilty of an inaccuracy William Hulme's Grammar School and at Owens College, sufficiently gross to merit correction on my part. In Manchester, Leslie Haden Guest continued his medical training at the London Hos- their brief and pejorative survey of the results of pital, qualifying M.R.C.S., psychotherapy of mental disorders, they say, inter alia: L.R.C.P. in 1900. After " Glover (1955) has disavowed any claims for the thera- serving as a civil surgeon in peutic usefulness of psycho-analytic methods." I the South African war he gather from their list of references that the disavowal remained in South Africa was made in my textbook The Technique of Psycho- for a time and then returned analysis. -

Twilight of the Godless: the Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle

Twilight of the Godless: The Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle WILLIAM CHRISTIE Edin r 13 Feb y 1830 My Dear Carlyle I am glad you think my regard for you a Mystery - as I am aware that must be its highest recommendation - I take it in an humbler sense - and am content to think it natural that one man of a kind heart should feel attracted towards another - and that a signal purity and loftiness of character, joined to great talents and something of a romantic history, should excite interest and respect. (NLS MS. 787, ff. 52-3) i I The Thomas Carlyle who knocked on Francis Jeffrey’s door at 92 George Street Edinburgh early in February of 1827 was not a young man. He was thirty two. And though Carlyle was of humble, country origins — he was the child of a rural stonemason turned small farmer — this was by no means his first time in the big city, having come here as a university student eighteen years before in 1809. Carlyle at thirty two, however, was as yet comparatively unknown, if not unpublished. His major publications — a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1824) and a Life of Schiller (1825) — had not brought his name before the English speaking reading public, probably because German thought and German literature simply did not interest them enough. Thomas Carlyle was an ambitious man and never doubted his own ability, but he must at this time have doubted his chances of success, and he had just added a young wife, Jane Welsh Carlyle, to his responsibilities.