NATARAJAN V. DIGNITY HEALTH S259364

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(OHCA) ARKANSAS St. Vincent Infirmary L

Organizations participating in the CommonSpirit Health Organized Health Care Arrangement (OHCA) ARKANSAS St. Vincent Infirmary Little Rock St. Vincent North Sherwood St, Vincent Hot Springs Hot Springs St. Vincent Morrilton Morrilton CHI St. Vincent Medical Group Little Rock CHI St. Vincent Medical Group Hot Springs GEORGIA CHI Memorial Georgia Hospital Fort Oglethorpe CHI Memorial - Parkway Ringgold IOWA CHI Health Mercy Council Bluffs Council Bluffs CHI Health Missouri Valley Missouri Valley CHI Health Mercy Corning Corning KENTUCKY Flaget Memorial Hospital Bardstown Saint Joseph Hospital Lexington, Nicholasville Saint Joseph - Berea Berea Saint Joseph East Lexington Saint Joseph London London Saint Joseph Mount Sterling Mount Sterling Continuing Care Hospital Lexington CHI Saint Joseph Medical Groups Central & Eastern Kentucky MINNESOTA CHI LakeWood Health Baudette CHI St. Francis Health Breckenridge CHI St. Joseph's Health Park Rapids CHI St.Gabriel's Health Little Falls CHI St. Francis Home Breckenridge CHI Health at Home All locations NEBRASKA CHI Health Lakeside Omaha CHI Health Midlands Papillion CHI Health Plainview Plainview Nebraska Spine Hospital Omaha CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center - Bergen Omaha Mercy Lasting Hope Recovery Center Omaha CHI Health Immanuel Omaha CHI Health Schuyler Schuyler CHI Health Good Samaritan Kearney CHI Health Richard Young Behavioral Health Kearney CHI Nebraska Heart Lincoln CHI Health St. Elizabeth Lincoln CHI Health St. Francis Grand Island CHI Health St. Mary's Nebraska City The Physician Network ( including Nebraska Specialty Network, and Lincoln Physician Network) All locations NORTH DAKOTA CHI St. Alexius Medical Center Bismarck CHI St. Alexius Health Carrington & Clinics Carrington CHI St. Alexius Carrington Urgent Care Carrington CHI Lisbon Health Lisbon CHI St. -

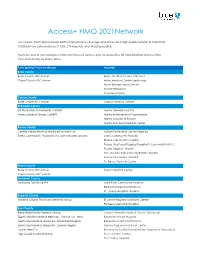

Access+ HMO 2021Network

Access+ HMO 2021Network Our Access+ HMO plan provides both comprehensive coverage and access to a high-quality network of more than 10,000 primary care physicians (PCPs), 270 hospitals, and 34,000 specialists. You have zero or low copayments for most covered services, plus no deductible for hospitalization or preventive care and virtually no claims forms. Participating Physician Groups Hospitals Butte County Butte County BSC Admin Enloe Medical Center Cohasset Glenn County BSC Admin Enloe Medical Center Esplanade Enloe Rehabilitation Center Orchard Hospital Oroville Hospital Colusa County Butte County BSC Admin Colusa Medical Center El Dorado County Hill Physicians Sacramento CalPERS Mercy General Hospital Mercy Medical Group CalPERS Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Mercy Hospital of Folsom Mercy San Juan Medical Center Fresno County Central Valley Medical Medical Providers Inc. Adventist Medical Center Reedley Sante Community Physicians Inc. Sante Health Systems Clovis Community Hospital Fresno Community Hospital Fresno Heart and Surgical Hospital A Community RMCC Fresno Surgical Hospital San Joaquin Valley Rehabilitation Hospital Selma Community Hospital St. Agnes Medical Center Glenn County Butte County BSC Admin Glenn Medical Center Glenn County BSC Admin Humboldt County Humboldt Del Norte IPA Mad River Community Hospital Redwood Memorial Hospital St. Joseph Hospital - Eureka Imperial County Imperial County Physicians Medical Group El Centro Regional Medical Center Pioneers Memorial Hospital Kern County Bakersfield Family Medical -

California Hospital Medical Center 2019 Community Health

California Hospital Medical Center 2019 Community Health Implementation Strategy Adopted October 2019 Table of Contents At-a-Glance Summary 3 Our Hospital and the Community Served 5 About California Hospital Medical Center 5 Our Mission 5 Financial Assistance for Medically Necessary Care 5 Description of the Community Served 5 Community Need Index 7 Community Assessment and Significant Needs 8 Community Health Needs Assessment 8 Significant Health Needs 8 2019 Implementation Strategy 9 Creating the Implementation Strategy 10 Strategy by Health Need 11 Program Digests 35 Hospital Board and Committee Rosters 46 2019 Community Health Implementation Strategy California Hospital Medical Center | 2 At-a-Glance Summary Community CHMC is located in a federally designated Medically Underserved Area and serves Served a Medically Underserved Population (MUA/P ID #04011) (Census tract 2240.10). While CHMC is located in Service Planning Area (SPA) 4 or Metro Los Angeles, its service area also includes parts of SPA 6 (South), SPA 7 (East) and SPA 8 (South Bay). CHMC serves 1,576,013 racially diverse residents with a median income of $40,705. 8% of adults in the hospital’s service area are homeless; the service area includes Skid Row that has the largest concentration of homeless in LA County. Significant The significant community health needs the hospital is helping to address and that Community form the basis of this document were identified in the hospital’s most recent Health Needs Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA). Needs being addressed by Being strategies and programs are: Addressed 1. Housing & homelessness 6. Substance use and misuse 2. -

Sacramento County Mercy Hospital of Folsom Mercy San Juan Medical Center Mercy General Hospital Methodist Hospital of Sacramento

Dignity Health – Sacramento County Mercy Hospital of Folsom Mercy San Juan Medical Center Mercy General Hospital Methodist Hospital of Sacramento 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment – Main Report Acknowledgements We are deeply grateful to all those who contributed to this community health needs assessment. Many dedicated healthcare practitioners, community health experts, and members of social-service organizations working with the most vulnerable members of the Sacramento County community gave their expertise and insights to help guide and inform the findings of this assessment. Further, many community residents volunteered their time to provide valuable information as well. We also appreciate the collaborative spirit of the consultants at Harder+Company and their willingness to share the information they gathered while conducting a health assessment in the Sacramento area for Kaiser Permanente. Last, we especially acknowledge the sponsors of this assessment, Dignity Health, Sutter Health, and UC Davis Medical Center, who, using the results of these CHNAs, continuously work to improve the health of the communities they serve. To everyone who supported this important work, we extend our deepest, heartfelt gratitude. Community Health Insights (www.communityhealthinsights.com) conducted the health assessment. Community Health Insights is a Sacramento-based research-oriented consulting firm dedicated to improving the health and well-being of communities across Northern California. This joint report was authored by: Dale Ainsworth, PhD, MSOD, Managing Partner of Community Health Insights and Assistant Professor of Health Science at California State University, Sacramento Heather Diaz, DrPH, MPH, Managing Partner of Community Health Insights and Professor of Health Science at California State University, Sacramento Mathew C. -

St. Mary's Medical Center

Dignity Health Research Institute Cardiology Research St. Mary’s Medical Center Cardiology Research About the Program Program St. Mary’s Medical Center is proud to be a part of multiple multi- center, national and international clinical research trials. The program St. Mary’s Medical Center in is led by dedicated physicians and professional research staff. San Francisco, part of the Dignity This team actively participates in numerous National Institutes of Health system, provides a Health studies and industry sponsored trials. comprehensive and collaborative The mission of the cardiology research program is to support approach to diagnosis and treatment continued innovation in the field of cardiovascular care, with the goal of cardiovascular disease and of finding new ways to provide timely and effective treatment to is nationally recognized for its patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. commitment to exceptional care. An important part of that commitment includes ongoing leadership in the About Dignity Health Research Institute field of cardiovascular research. At Dignity Health, we strongly believe in the benefits of clinical The physicians and staff of the research and are committed to leading the way in the advancement and use of new and evolving technology and procedures. Our vast St. Mary’s Medical Center are research program speaks to this commitment. focused on identifying new technology, procedures and devices Dignity Health as a system offers more than 1,000 active clinical that will positively impact our patients, trials and research protocols to its patients in Arizona, California improving their symptoms, their and Nevada. prognosis and their quality of life. Dignity Health Research Institute for California & Nevada provides centralized research administration infrastructure and support including contracting, budgeting, financial management and IRB oversight for all research sites across our California & Nevada markets. -

Dignity Health-CHI San Francisco County Health Impact Report

Effect of the Ministry Alignment Agreement between Dignity Health and Catholic Health Initiatives on the Availability and Accessibility of Healthcare Services to the Communities Served by Dignity Health’s Hospitals Located in the City and County of San Francisco Prepared for the Office of the California Attorney General August 10, 2018 © 2018 Vizient, Inc. and JD Healthcare. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Introduction & Purpose .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Background & Description of the Transaction ................................................................................ 7 Background ................................................................................................................................. 7 Transaction Process & Timing ..................................................................................................... 7 Summary of the Ministry Alignment Agreement ..................................................................... 10 System Corporation Post the Effective Date of the Ministry Alignment Agreement ............... 11 System Corporation Post Debt Consolidation (Within 36 Months) ........................................ -

Methodist Hospital of Sacramento

Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Community Health Implementation Strategy 2016-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Mission, Vision, and Values 4 Our Hospital and Our Commitment 5 Description of the Community Served 8 Implementation Strategy Development Process Community Health Needs Assessment Process 11 CHNA Significant Health Needs 12 Creating the Implementation Strategy 13 Planning for the Uninsured/Underinsured Patient Population 14 2016-2018 Implementation Strategy Strategy and Program Plan Summary 15 Anticipated Impact 18 Planned Collaboration 19 Program Digests 20 Appendices Appendix A: Community Board and Committee Rosters 28 Appendix B: Other Programs and Non-Quantifiable Benefits 30 Appendix C: Financial Assistance Policy Summary 31 Methodist Hospital of Sacramento 2016-2018 Implementation Strategy 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Methodist Hospital of Sacramento (Methodist Hospital) opened in 1973, after a decade-long effort to expand health care services for residents in the south area of Sacramento, CA. Located at 7500 Hospital Drive, the hospital became a member of Dignity Health in 1993, and today has 1,150 employees, 162 licensed acute care beds, and 29 emergency department beds. Methodist Hospital also operates Bruceville Terrace, a 171-bed, sub-acute skilled nursing long-term care facility that provides for the elderly, as well as those requiring extended recoveries. Communities in south Sacramento also suffer from a shortage in community providers and capacity that limits access to appropriate care. As a result, Methodist Hospital fills a major gap in needed safety net services. Hospital utilization trends show that the numbers of individuals turning to the emergency department for basic primary care needs that cannot be met elsewhere continue to rise at alarming rates. -

Sequoia Hospital 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Volume 1: Main Report

Sequoia Hospital 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Volume 1: Main Report This report includes two volumes, the Main Report and Detailed Data Attachments, both of which are widely available to the public on dignityhealth.org/sequoia. 1. Acknowledgements HEALTHY COMMUNITY COLLABORATIVE (HCC) MEMBERS The Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) could not have been completed without the HCC’s efforts, tremendous input, many hours of dedication, and financial support. We wish to acknowledge the following organizations for their representatives’ contributions to promoting the health and well-being of San Mateo County. Dignity Health Sequoia Hospital Marie Violet, Director, Heath & Wellness Co-Chair, Healthy Community Collaborative [email protected] Tricia Coffey, Manager of Community Health [email protected] San Mateo County Health System Scott Morrow, MD, MPH, MBA, FACPM Health Officer, San Mateo County Co-Chair, Healthy Community Collaborative [email protected] Cassius Lockett, PhD, Director of Public Health, Policy, and Planning [email protected] Karen Pfister, MS, Supervising Epidemiologist [email protected] Hospital Consortium of San Mateo County Francine Serafin-Dickson, DNP, MBA, RN, Executive Director [email protected] County of San Mateo Human Services Agency Selina Toy Lee, MSW, Director of Collaborative Community Outcomes [email protected] Kaiser Permanente, San Mateo Area James Illig, Community Health Manager Kaiser Foundation Hospital, South San Francisco [email protected] Stephan -

Virtual Health/Wellness Virtual Benefits Fair

2021 Open Enrollment Virtual Health/Wellness Virtual Benefits Fair Welcome to the 2021 State Judicial Branch Open Enrollment Virtual Health/Wellness Virtual Benefits Fair. The open enrollment period is from September 20, 2021 through October 15, 2021. During this timeframe, you will be able to enroll, cancel, and/or change your election to the following plan(s): Medical Dental Vision Flex Elect Plans (Reimbursement and Cash Option) Long Term Disability Group Legal Services Insurance Plan To assist you in making informed decisions about your healthcare, the Judicial Council Human Resources office has compiled information from the plan administrators which you can access at your convenience. Below is a summary of information contained in this document: Health Plan Changes for 2022 (New): Summary of health plan changes for the upcoming 2022 plan year. Healthier U Connections (New): The California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) hosted a virtual Open Enrollment fair for state employees. Employees will be able to view on-demand webinars for all benefit plans on the Healthier U Connections (initial registration will be required for this website). Online Presentations: Includes live webinars, on-demand webinars, recorded presentations, virtual/interactive platforms, and other educational videos Benefit Summary: Summary of benefit documents, evidence of coverage booklets, program guides, comparison charts, plan summaries, overviews, and newsletters. Helpful Links: Provider/location directories, member guides, enrollment brochures/kits, digital publications, frequently asked questions, and calculators/estimator tools. If you have any additional questions, please contact your assigned Judicial Council Pay and Benefits representative. 1 Health Plan Changes for 2022 Plan Year Listed below is a summary of the health plan changes for the 2022 plan year. -

Nevada Leadership

Nevada Leadership Lawrence C. Barnard, MBA President and CEO Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican, Siena Campus Market Leader, Dignity Health Nevada Lawrence “Larry” Barnard was named President and CEO of Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican, Siena Campus in July 2019. He was also named Market Leader for Dignity Health Nevada, the organization’s lead ambassador to the growing southern Nevada community. Mr. Barnard has an extensive range of health-care administrative experience. He joined Dignity Health as the President/CEO of St. Rose Dominican, San Martín Campus in December 2015. At the San Martín Campus, Mr. Barnard’s leadership played a significant role in cultivating a cohesive, high-performing team which achieved some of the best patient care and performance results in the Dignity Health ministry. Prior to joining Dignity Health Mr. Barnard served as Chief Operating Officer, then Chief Executive Officer of University Medical Center in Las Vegas. He has also served in hospital administration at various facilities in Nevada, southern California and South Carolina. Mr. Barnard is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and served as a U. S. Army captain as a helicopter and fixed wing pilot. He received an MBA from the University of Southern California’s Marshal School of Business. Larry has made his home in Las Vegas since 2009, with his wife Kori and their four children. Kimberly Shaw, MBA, BSN, RN President/CEO Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican, San Martín Campus Kimberly Shaw was named President/CEO for the St. Rose Dominican, San Martín Campus in July 2019. -

Blue Shield of California, Catholic Healthcare West

Blue Shield of California, Catholic Healthcare West and Hill Physicians Medical Group to Pilot Innovative New Care Model for CalPERS Organizations collaborate to deliver quality, cost-effective care SACRAMENTO, CA – April 22, 2009 – This afternoon, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) approved a new pilot program in Sacramento that aims to reduce costs while improving healthcare quality. The program, led by Blue Shield of California, Hill Physicians Medical Group and Catholic Healthcare West, which operates the local Mercy hospitals, will deliver comprehensive healthcare services to CalPERS members using a “virtual integrated model” of care. The health plan, hospital system, and medical group will be partnering to share information and coordinate care more directly. The three organizations’ incentives will all be aligned to improve quality, cost and service. The pilot project will begin in calendar year 2010. “This is right in line with our strategic vision to be a leader in providing best-in-class, quality, and sustainable health benefit options for our members and employers,” said Rob Feckner, CalPERS Board President. “In the short-term, we’re aiming to reduce our cost and improve delivery of health care in the Sacramento region. If successful, we hope to positively impact health outcomes and costs for more of our members over the long-term.” Disease management, pharmacy, improved communication and palliative care are all slated to play a role in this pilot, which is still in the earliest stages of development. Each partner has agreed to contribute to cost savings and to be at financial risk for any variance from the pilot’s targeted cost reduction goals. -

Improving Clinical Communications at Dignity Health's St. Joseph's

Improving clinical communications at Dignity Health’s St. Joseph’s Medical Center A value analysis of PerfectServe’s impact on hospital operations October 2012 Contents Executive summary 3 The case for improving clinical communications 3 Key technologies enabling clinical communications improvement 6 Dignity Health’s St. Joseph’s Medical Center 7 Study approach and methodology 8 Benefits analysis 11 Closing remarks 21 About Maestro Strategies™ 22 About PerfectServe® 22 References 23 perfectserve.com | 866.844.5484 | @PerfectServe Published as a source of information only. The material contained herein is not to be construed as legal advice or opinion. ©2015 PerfectServe, Inc. All rights reserved. PerfectServe® is a registered trademark and PerfectServe Synchrony™ and Problem Solved™ are trademarks of PerfectServe, Inc. 2 Executive summary Today’s healthcare delivery landscape is changing rapidly. With healthcare reform legislation and healthcare payment reform at the forefront, more emphasis is being placed on efficient coordination of care across settings and ensuring access to care. Effective communications within and among the care team are essential to safe, high quality care, efficient care coordination and access management. PerfectServe, a company that provides a next-generation, clinical communications platform which makes it easy for clinicians to connect with each other, engaged Maestro Strategies, a nationally recognized healthcare strategy and transformation firm, to complete an independent, third-party evaluation of PerfectServe’s impact and value on hospital operations. This paper examines the experience of one hospital, St. Joseph’s Medical Center of Stockton, California, and its initial implementation of the PerfectServe clinical communications platform. Multiple benefits associated with the PerfectServe implementation were identified, including enhanced patient throughput, improved clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction related to quietness scores.