Pygmalion & Galatea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donizetti Operas and Revisions

GAETANO DONIZETTI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Il Pigmalione (1816), libretto adapted from A. S. Sografi First performed: Believed not to have been performed until October 13, 1960 at Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. • L'ira d'Achille (1817), scenes from a libretto, possibly by Romani, originally done for an opera by Nicolini. First performed: Possibly at Bologna where he was studying. First modern performance in Bergamo, 1998. • Enrico di Borgogna (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: November 14, 1818 at Teatro San Luca, Venice. • Una follia (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: December 15, 1818 at Teatro San Luca,Venice. • Le nozze in villa (1819), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: During Carnival 1820-21 at Teatro Vecchio, Mantua. • Il falegname di Livonia (also known as Pietro, il grande, tsar delle Russie) (1819), libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini First performed: December 26, 1819 at the Teatro San Samuele, Venice. • Zoraida di Granata (1822), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: January 28, 1822 at the Teatro Argentina, Rome. • La zingara (1822), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: May 12, 1822 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. • La lettera anonima (1822), libretto by Giulio Genoino First performed: June 29, 1822 at the Teatro del Fondo, Naples. • Chiara e Serafina (also known as I pirati) (1822), libretto by Felice Romani First performed: October 26, 1822 at La Scala, Milan. • Alfredo il grande (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: July 2, 1823 at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples. • Il fortunate inganno (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: September 3, 1823 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor

LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR An in-depth guide by Stu Lewis INTRODUCTION In Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857), Western literature’s prototypical “Desperate Housewives” narrative, Charles and Emma Bovary travel to Rouen to attend the opera, and they attend a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor. Perhaps Flaubert chose this opera because it would appeal to Emma’s romantic nature, suggesting parallels between her life and that of the heroine: both women forced into unhappy marriages. But the reason could have been simpler—that given the popularity of this opera, someone who dropped in at the opera house on a given night would be likely to see Lucia. If there is one work that could be said to represent opera with a capital O, it is Lucia di Lammermoor. Lucia is a story of forbidden love, deceit, treachery, violence, family hatred, and suicide, culminating in the mother of all mad scenes. It features a heroic yet tragic tenor, villainous baritones and basses, a soprano with plenty of opportunity to show off her brilliant high notes and trills and every other trick she learned in the conservatory, and, to top it off, a mysterious ghost haunting the Scottish Highlands. This is not to say that Donizetti employed clichés, but rather that what was fresh and original in Donizetti's hands became clichés in the works of lesser composers. As Emma Bovary watched the opera, “She filled her heart with the melodious laments as they slowly floated up to her accompanied by the strains of the double basses, like the cries of a castaway in the tumult of a storm. -

TAG SCRIPT LIBRARY Nov 2013.Xlsx

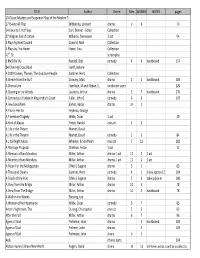

TITLE Author Genre Men WOMEN NOTES pages 10 Classic Mystery and Suspense Plays of the Modern T 1776‐And All That Wibberley, Leonard drama 98 70 24 Favorite 1 Act Plays Cerf, Bennet ‐ Editor Collection 27 Wagons Full of Cotton Williams, Tennessee 1 act 54 3 Plays by Noel Coward Coward, Noel Collection 3 Plays by Tina Howe Howe, Tina Collection 42nd St. screenplay 6 RMS RIV VU Randall, Bob comedy 4 4 hardbound 157 84 Charring Cross Road Hanff, Helene A 1000 Clowns, Thieves, The Goodbye People Gardner, Herb Collection A Breeze from the Gulf Crowley, Mart drama 2 1 hardbound 184 A Chorus Line Hamlisch, M.and Kleban, E, . conductor score 220 A Clearing in the Woods Laurents, Arthur drama 5 5 hardbound 170 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Fuller, John G. comedy 6 6 147 A Few Good Men Sorkin, Aaron drama 14 1 A Flea in Her Ear Feydeau, George A Florentine Tragedy Wilde, Oscar 1 act 20 A Kind of Alaska Pinter, Harold one act 1 2 A Life in the Theare Mamet, David A Life in the Theatre Mamet, David comedy 2 0 84 A Little Night Music Wheeler, & Sondheim musical 7 11 182 A Marriage Proposal Chekhov, Anton 1 act 12 A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Moon For the Misbegotten O'Neill, Eugene drama 3 1 83 A Thousand Clowns Gardner, Herb comedy 4 1 1 boy approx 12 104 A Touch of the Poet O'Neill, Eugene drama 7 3 takes place in 180 A View from the Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 78 A View From The Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 hardbound 78 A Walk -

Grand Finals Concert

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Carlo Rizzi National Council Auditions host Grand Finals Concert Anthony Roth Costanzo Sunday, March 31, 2019 3:00 PM guest artist Christian Van Horn Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Carlo Rizzi host Anthony Roth Costanzo guest artist Christian Van Horn “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Meghan Kasanders, Soprano “Fra poco a me ricovero … Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” from Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti) Dashuai Chen, Tenor “Oh! quante volte, oh! quante” from I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini) Elena Villalón, Soprano “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis” (Lenski’s Aria) from Today’s concert is Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky) being recorded for Miles Mykkanen, Tenor future broadcast “Addio, addio, o miei sospiri” from Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) over many public Michaela Wolz, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Seul sur la terre” from Dom Sébastien (Donizetti) local listings. Piotr Buszewski, Tenor Sunday, March 31, 2019, 3:00PM “Captain Ahab? I must speak with you” from Moby Dick (Jake Heggie) Thomas Glass, Baritone “Don Ottavio, son morta! ... Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Alaysha Fox, Soprano “Sorge infausta una procella” from Orlando (Handel) -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

Note Al Programma

NOTE AL PROGRAMMA Berlino, al centro del continente europeo e della sua storia, è sempre stata in grado di rivelare, in ogni epoca, da che parte spirasse il vento, rappresentando il fulcro della modernità occidentale quanto ad arte, musica, cultura e pensiero politico. Agli inizi degli Anni Trenta del secolo scorso l’aria che tirava era fortemente condizionata dal Nazismo. La crisi economica derivante dal crollo di Wall Street nel ’29 e la disoccupazione dilagante nella Repubblica di Weimar avevano posto le basi a un cambiamento politico che, per una città così vitale e aperta alla diversità e ai dibattiti d’ogni tendenza, rappresentava una grossa stonatura. Dal disagio sociale i nazisti avevano tratto beneficio e potere, e inculcarono nel pensiero comune che le colpe di quel dissesto fossero da imputare alla popolazione di discendenza ebraica. E l’incolpare gli ebrei di ogni fatto qualunque, perfino meteorologico, divenne per tutti un luogo comune. La devastazione, nel novembre del ’38, delle vetrine dei negozi appartenenti a commercianti ebrei fu la prova di una strada ormai segnata e senza ritorno. Mentre una legge stabiliva che quei danni dovessero «essere immediatamente riparati [dagli stessi] titolari e dai dirigenti ebrei [e a loro spese]», in città v’era uno spazio in cui tutto questo, oltre al quotidiano, diventava materia di un discorso comune, capace di cogliere l’ironia da ogni fatto rovesciando l’umore di ciascun cittadino: era il cabaret. Esisteva da tempo, il cabaret, come palcoscenico irriverente e beffardo sull’attualità. Ma nel periodo nazista questo divenne inevitabilmente il nucleo di grandi contraddizioni e di conflitti ideologici. -

Der Kuhhandel

Volume 22 Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Der Kuhhandel In this Issue: Bregenz Festival Reviewed Feature Article about Weill and An Operetta Resurfaces Operetta Volume 22 In this issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Note from the Editor 3 Letters 3 ISSN 0899-6407 Bregenz Festival © 2004 Kurt Weill Foundation for Music Der Protagonist / Royal Palace 4 7 East 20th Street Horst Koegler New York, NY 10003-1106 Der Kuhhandel 6 tel. (212) 505-5240 Larry L. Lash fax (212) 353-9663 Zaubernacht 8 Horst Koegler Published twice a year, the Kurt Weill Newsletter features articles and reviews (books, performances, recordings) that center on Kurt Weill but take a broader look at issues of twentieth-century music Feature and theater. With a print run of 5,000 copies, the Newsletter is dis- Weill, the Operettenkrise, and the tributed worldwide. Subscriptions are free. The editor welcomes Offenbach Renaissance 9 the submission of articles, reviews, and news items for inclusion in Joel Galand future issues. A variety of opinions are expressed in the Newsletter; they do not Books necessarily represent the publisher's official viewpoint. Letters to the editor are welcome. Dialog der Künste: Die Zusammenarbeit von Kurt Weill und Yvan Goll 16 by Ricarda Wackers Esbjörn Nyström Staff Elmar Juchem, Editor Carolyn Weber, Associate Editor Performances Dave Stein, Associate Editor Teva Kukan, Production Here Lies Jenny in New York 18 William V. Madison Kurt Weill Foundation Trustees Kim Kowalke, President Paul Epstein Der Zar lässt sich photographieren -

An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2011 An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill Elizabeth Rose Williamson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Williamson, Elizabeth Rose, "An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill" (2011). Honors Theses. 2157. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2157 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND MUSICAL ADAPTATION IN VOCAL COMPOSITIONS OF KURT WEILL by Elizabeth Rose Williamson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2011 Approved by Reader: Professor Corina Petrescu Reader: Professor Charles Gates I T46S 2^1 © 2007 Elizabeth Rose Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people of the Kurt Weill Zentrum in Dessau Gennany who graciously worked with me despite the reconstruction in the facility. They opened their resources to me and were willing to answer any and all questions. Thanks to Clay Terry, I was able to have an uproariously hilarious ending number to my recital with “Song of the Rhineland.” I thank Dr. Charles Gates for his attention and interest in my work. -

Marino Faliero

www.ferragamo.com VENEZIA Calle Larga XXII Marzo, 2093 FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA Paolo Costa presidente Cesare De Michelis Pierdomenico Gallo Achille Rosario Grasso Mario Rigo Valter Varotto Giampaolo Vianello consiglieri Giampaolo Vianello sovrintendente Sergio Segalini direttore artistico Marcello Viotti direttore musicale Angelo Di Mico presidente Luigi Braga Adriano Olivetti Maurizia Zuanich Fischer SOCIETÀ DI REVISIONE PricewaterhouseCoopers S.p.A. Marino Faliero La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2002-2003 8 FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA Marino Faliero azione tragica in tre atti libretto di Giovanni Emanuele Bidera musica di Gaetano Donizetti Teatro Malibran venerdì 20 giugno 2003 ore 20.00 turni A-Q domenica 22 giugno 2003 ore 15.30 turno B martedì 24 giugno 2003 ore 20.00 turni D-R venerdì 27 giugno 2003 ore 20.00 turni E-H domenica 29 giugno 2003 ore 15.30 turni C-I-V Gaetano Donizetti all’epoca di Zoraida di Granata (Roma, Teatro Argentina, 1822). Miniatura su avorio. Sommario 7 La locandina 9 «È traditor chi è vinto / E tal son io» di Michele Girardi 11 Marino Faliero: libretto e guida all’opera a cura di Giorgio Pagannone 63 Marino Faliero in breve a cura di Gianni Ruffin 65 Argomento – Argument – Synopsis – Handlung 73 Paolo Fabbri «Fosca notte, notte orrenda» 89 Francesco Bellotto L’immaginario scenico del Marino Faliero 103 Guido Paduano L’individuo e lo stato. Byron, Delavigne, Donizetti 128 Il contratto del Marino Faliero 133 Emanuele Bidera Marino Faliero, libretto della prima versione, a cura di Maria Chiara Bertieri 151 Francesco Bellotto Bibliografia 157 Online: Marin Faliero «dux VeNETiarum» a cura di Roberto Campanella 165 Gaetano Donizetti a cura di Mirko Schipilliti Il frontespizio del libretto pubblicato per la prima italiana (Firenze, 1836). -

Street Scene

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene A Study Guide prepared by VIRGINIA OPERA 1 Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of World Premiere 3 Cast of Characters 3 Musical numbers 4 Brief plot summary 5 Full plot synopsis with musical examples 5 Historical background 12 The creation of the opera 13 Relevance of social themes in 21st century America 15 Notable features of musical style 16 Discussion questions 19 3 STREET SCENE AN AMERICAN OPERA Music by KURT WEILL Book by ELMER RICE, adapted from his play of the same name Lyrics by LANGSTON HUGHES Premiere First performance on January 9, 1947 at the Adelphi Theater in New York City Setting The action takes place outside a tenement house in New York City on an evening in June 1946. -

LA FAVORITE Di Gaetano Donizetti a TEATRO CON LA LUTE

A TEATRO CON LA LUTE LA FAVORITE di Gaetano Donizetti Contenuti, impaginazione e foto a cura di Elvira Valentina Resta gruppo LUTE TEATRO La Favorite Grand-opéra in quattro atti Libretto di Alphonse Royer e Gustave Vaëz Musica di Gaetano Donizetti Direttore Francesco Lanzillotta Regia Allex Aguilera Scene e costumi Francesco Zito Luci Caetano Vilela Coreografia Carmen Marcuccio Assistente alle scene Antonella Conte Assistente ai costumi Ilaria Ariemme Orchestra, Coro e Corpo di ballo del Teatro Massimo Nuovo allestimento del Teatro Massimo Cast Léonor Raehann Bryce-Davis Ines Clara Polito Fernand Giorgio Misseri Alphonse Mattia Olivieri Balthazar Riccardo Fassi Don Gaspar Blagoj Nacoski Direttore D’Orchestra Francesco Lanzillotta Francesco Lanzillotta è considerato uno dei più interessanti direttori nel panorama musicale italiano. Negli ultimi anni ha diretto nei più importanti teatri italiani, fra i quali Teatro La Fenice di Venezia,Teatro San Carlo di Napoli, Teatro Verdi di Trieste, Teatro Filarmonico di Verona e Teatro Lirico di Cagliari. È regolarmente ospite di importanti compagini orchestrali, fra le quali l’ Orchestra Nazionale della RAI di Torino, Or- chestra della Svizzera Italiana, Orchestra I Pomeriggi Musicali di Milano, Orchestra Haydn di Bolzano, Filarmonica To- scanini di Parma, Orchestra Regionale Toscana, Orchestra del Teatro Filarmonico di Verona, Orchestra del Teatro San Carlo di Napoli, Orchestra del Teatro Verdi di Trieste, Gyeonggi Philharmonic Orchestra di Suwon (Korea) e Sofia Phi- lharmonic Orchestra. Direttore Principale Ospite del Teatro dell’Opera di Varna in Bulgaria, vi ha ivi diretto produzioni quali Cavalleria Rusti- cana, Pagliacci,Le nozze di Figaro, La bohème, Tosca, La Traviata, Carmen. Nel corso della stagione 2012/13 ha compiuto il prestigioso debutto sul podio dell’Orchestra Sinfonica della RAI di Torino con un programma dedicato a Stravinskij e Berlioz. -

A Performer's Guide to the American Theater Songs of Kurt Weill

A Performer's Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Morales, Robin Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:09:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194115 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATER SONGS OF KURT WEILL (1900-1950) by Robin Lee Morales ________________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As member of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read document prepared by Robin Lee Morales entitled A Performer’s Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Faye L. Robinson_________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Edmund V. Grayson Hirst__________________ Date: May 5, 2008 John T. Brobeck _________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement.