Social Problems in the Comedy “Pygmalion” by B. Shaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

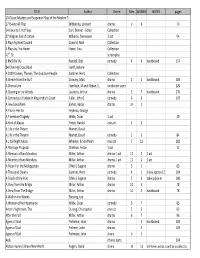

TAG SCRIPT LIBRARY Nov 2013.Xlsx

TITLE Author Genre Men WOMEN NOTES pages 10 Classic Mystery and Suspense Plays of the Modern T 1776‐And All That Wibberley, Leonard drama 98 70 24 Favorite 1 Act Plays Cerf, Bennet ‐ Editor Collection 27 Wagons Full of Cotton Williams, Tennessee 1 act 54 3 Plays by Noel Coward Coward, Noel Collection 3 Plays by Tina Howe Howe, Tina Collection 42nd St. screenplay 6 RMS RIV VU Randall, Bob comedy 4 4 hardbound 157 84 Charring Cross Road Hanff, Helene A 1000 Clowns, Thieves, The Goodbye People Gardner, Herb Collection A Breeze from the Gulf Crowley, Mart drama 2 1 hardbound 184 A Chorus Line Hamlisch, M.and Kleban, E, . conductor score 220 A Clearing in the Woods Laurents, Arthur drama 5 5 hardbound 170 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Fuller, John G. comedy 6 6 147 A Few Good Men Sorkin, Aaron drama 14 1 A Flea in Her Ear Feydeau, George A Florentine Tragedy Wilde, Oscar 1 act 20 A Kind of Alaska Pinter, Harold one act 1 2 A Life in the Theare Mamet, David A Life in the Theatre Mamet, David comedy 2 0 84 A Little Night Music Wheeler, & Sondheim musical 7 11 182 A Marriage Proposal Chekhov, Anton 1 act 12 A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Moon For the Misbegotten O'Neill, Eugene drama 3 1 83 A Thousand Clowns Gardner, Herb comedy 4 1 1 boy approx 12 104 A Touch of the Poet O'Neill, Eugene drama 7 3 takes place in 180 A View from the Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 78 A View From The Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 hardbound 78 A Walk -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

Note Al Programma

NOTE AL PROGRAMMA Berlino, al centro del continente europeo e della sua storia, è sempre stata in grado di rivelare, in ogni epoca, da che parte spirasse il vento, rappresentando il fulcro della modernità occidentale quanto ad arte, musica, cultura e pensiero politico. Agli inizi degli Anni Trenta del secolo scorso l’aria che tirava era fortemente condizionata dal Nazismo. La crisi economica derivante dal crollo di Wall Street nel ’29 e la disoccupazione dilagante nella Repubblica di Weimar avevano posto le basi a un cambiamento politico che, per una città così vitale e aperta alla diversità e ai dibattiti d’ogni tendenza, rappresentava una grossa stonatura. Dal disagio sociale i nazisti avevano tratto beneficio e potere, e inculcarono nel pensiero comune che le colpe di quel dissesto fossero da imputare alla popolazione di discendenza ebraica. E l’incolpare gli ebrei di ogni fatto qualunque, perfino meteorologico, divenne per tutti un luogo comune. La devastazione, nel novembre del ’38, delle vetrine dei negozi appartenenti a commercianti ebrei fu la prova di una strada ormai segnata e senza ritorno. Mentre una legge stabiliva che quei danni dovessero «essere immediatamente riparati [dagli stessi] titolari e dai dirigenti ebrei [e a loro spese]», in città v’era uno spazio in cui tutto questo, oltre al quotidiano, diventava materia di un discorso comune, capace di cogliere l’ironia da ogni fatto rovesciando l’umore di ciascun cittadino: era il cabaret. Esisteva da tempo, il cabaret, come palcoscenico irriverente e beffardo sull’attualità. Ma nel periodo nazista questo divenne inevitabilmente il nucleo di grandi contraddizioni e di conflitti ideologici. -

Der Kuhhandel

Volume 22 Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Der Kuhhandel In this Issue: Bregenz Festival Reviewed Feature Article about Weill and An Operetta Resurfaces Operetta Volume 22 In this issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Note from the Editor 3 Letters 3 ISSN 0899-6407 Bregenz Festival © 2004 Kurt Weill Foundation for Music Der Protagonist / Royal Palace 4 7 East 20th Street Horst Koegler New York, NY 10003-1106 Der Kuhhandel 6 tel. (212) 505-5240 Larry L. Lash fax (212) 353-9663 Zaubernacht 8 Horst Koegler Published twice a year, the Kurt Weill Newsletter features articles and reviews (books, performances, recordings) that center on Kurt Weill but take a broader look at issues of twentieth-century music Feature and theater. With a print run of 5,000 copies, the Newsletter is dis- Weill, the Operettenkrise, and the tributed worldwide. Subscriptions are free. The editor welcomes Offenbach Renaissance 9 the submission of articles, reviews, and news items for inclusion in Joel Galand future issues. A variety of opinions are expressed in the Newsletter; they do not Books necessarily represent the publisher's official viewpoint. Letters to the editor are welcome. Dialog der Künste: Die Zusammenarbeit von Kurt Weill und Yvan Goll 16 by Ricarda Wackers Esbjörn Nyström Staff Elmar Juchem, Editor Carolyn Weber, Associate Editor Performances Dave Stein, Associate Editor Teva Kukan, Production Here Lies Jenny in New York 18 William V. Madison Kurt Weill Foundation Trustees Kim Kowalke, President Paul Epstein Der Zar lässt sich photographieren -

An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2011 An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill Elizabeth Rose Williamson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Williamson, Elizabeth Rose, "An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill" (2011). Honors Theses. 2157. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2157 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND MUSICAL ADAPTATION IN VOCAL COMPOSITIONS OF KURT WEILL by Elizabeth Rose Williamson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2011 Approved by Reader: Professor Corina Petrescu Reader: Professor Charles Gates I T46S 2^1 © 2007 Elizabeth Rose Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people of the Kurt Weill Zentrum in Dessau Gennany who graciously worked with me despite the reconstruction in the facility. They opened their resources to me and were willing to answer any and all questions. Thanks to Clay Terry, I was able to have an uproariously hilarious ending number to my recital with “Song of the Rhineland.” I thank Dr. Charles Gates for his attention and interest in my work. -

Street Scene

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene A Study Guide prepared by VIRGINIA OPERA 1 Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of World Premiere 3 Cast of Characters 3 Musical numbers 4 Brief plot summary 5 Full plot synopsis with musical examples 5 Historical background 12 The creation of the opera 13 Relevance of social themes in 21st century America 15 Notable features of musical style 16 Discussion questions 19 3 STREET SCENE AN AMERICAN OPERA Music by KURT WEILL Book by ELMER RICE, adapted from his play of the same name Lyrics by LANGSTON HUGHES Premiere First performance on January 9, 1947 at the Adelphi Theater in New York City Setting The action takes place outside a tenement house in New York City on an evening in June 1946. -

A Performer's Guide to the American Theater Songs of Kurt Weill

A Performer's Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Morales, Robin Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:09:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194115 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATER SONGS OF KURT WEILL (1900-1950) by Robin Lee Morales ________________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As member of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read document prepared by Robin Lee Morales entitled A Performer’s Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Faye L. Robinson_________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Edmund V. Grayson Hirst__________________ Date: May 5, 2008 John T. Brobeck _________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Touch of Venus Essen 31.05.Indd

Folkwang Universität der Künste Di_31. Mai 2011| 19.30 Uhr Mi_01. Juni | 19.30 Uhr Fr_03. Juni | 19.30 Uhr Sa_04. Juni | 19.30 Uhr Neue Aula ONE TOUCH OF VENUS _das Folkwang Musical 2011 _mit Absolventen des Studiengangs Musical u.a. _Musikalische Leitung: Patricia Martin _Regie: Reinhardt Friese (a.G.) Hinweis: Bild- und Tonmitschnitte sind nicht erlaubt! _Choreographie: Kurt Schrepfer (a.G.) Redaktion: Kommunikation & Medien, Folkwang Universität der Künste _Musical von Kurt Weill (Musik) und Ogden Nash (Liedtexte) Folkwang Universität der Künste | Klemensborn 39 | D-45239 Essen | Tel. +49 (0) 201.49 03-0 | www.folkwang-uni.de Matthias Kreinz Besetzung & Stab Der 1987 geborene Zürcher steht seit seinem siebten Lebensjahr auf der Bühne. VENUS, eine Göttin aus Anatolien Miriam Schwan Bereits vor seinem Studium an der Folkwang RODNEY HATCH, Friseur Andreas Bongard Universität der Künste spielte er in der Schweiz WHITELAW SAVORY, Kunstliebhaber Matthias Kreinz unter anderem Audrey Zwo in „Der kleine MOLLY GRANT, Savorys Assistentin Verena Mackenberg Horrorladen“ und den Matrosen in Cole Porters GLORIA KRAMER, Rodneys Verlobte Michèle Fichtner „Anything goes“. In Essen war er als DAMADGW TAXI BLACK, Privatdetektiv Stefan Preuth in „High Fidelity – Das Musical“ am Theater im Rathaus zu sehen und spielte Linus in „Du bist STANLEY, Taxi Blacks Assistent Oliver Morschel in Ordnung, Charlie Brown“. 2010 bekam er in MRS. KRAMER, Glorias Mutter Marie Lumpp Zürich den renommierten Schauspiel-Förder- preis der Armin Ziegler-Stiftung. DR. CRIPPEN Stefan Preuth In „One Touch of Venus“ spielt er den exzen- BELLE ELMORE, seine Ehefrau Julia Meier trischen Kunstsammler Whitelaw Savory. ETHEL LE NEVE, seine Schreibkraft Victoria Reich ZUVETLI, ein konservativer Anatolier David Johnston ANATOLIER Julia Meier, Victoria Reich Stefan Preuth MRS. -

Ein Hauch Von Venus

EIN HAUCH VON VENUS Originaltitel: ONE TOUCH OF VENUS Genre: Musical Autoren: Musical Comedy in zwei Akten Musik von Kurt Weill Buch von S. J. Perelman und Ogden Nash Songtexte Ogden Nash Nach „The Tinted Venus" von F. Anstey Neue deutsche Fassung von Roman Hinze (2019) Inhalt: "The show is ageless... The Weill score is as varied as it is melodic, with waltzes and ballads sharing the stage with a barbershop quartet . The artfulness in unison of music, lyrics and libretto make this musical well worth rediscovering." The New York Times, 1987 Unter Verwendung des antiken Sagenstoffs der schönen Galathee, die als Statue zu Leben erwacht, und der Novelle von Guthrie entstand eine Liebeskomödie im New York der vierziger Jahre. Aus einer Laune heraus steckt Rodney, ein junger Friseur, einer Venusstatue im Museum den für seine Braut Gloria vorgesehenen Verlobungsring an den Finger. Venus wird lebendig und verfolgt ihn mit Leidenschaft. Gloria wird von ihr an den Nordpol verbannt. Rodney und Venus landen im Gefängnis, da man ihnen den Raub einer Statue und das unerklärliche Verschwinden Glorias anlastet. Als die launische Liebesgöttin erfährt, dass sie als Gattin Rodneys ihr Leben in einem Frisiersalon verbringen soll, verwandelt sie sich wieder in Marmor zurück. Für ONE TOUCH OF VENUS schrieb Kurt Weill einige seiner bekanntesten Songs, darunter „I'm a Stranger Here Myself", „Speak Low" und „Foolish Heart". Für die Titelrolle hatte sich der Komponist ursprünglich Marlene Dietrich gewünscht, die die Partie jedoch "zu sexy" gefunden haben soll. Stattdessen begann für Mary Martin als Venus eine große Broadwaykarriere. Ausführliche Informationen zu ONE TOUCH OF VENUS finden Sie auf den Internetseiten der Kurt Weill Foundation. -

The Film Musical? a Proposal for a Genre Definition

The film musical? A proposal for a genre definition Marida Rizzuti IULM - Libera Università di Lingue e Comunicazione [email protected] The passage of the musical from the theatre to the cinema saw a transformation in its language; it entered a no man’s land (Iser 2000) be- tween what was ‘no longer’ theatrical and ‘not yet’ cinematographic. Musicals on the silver screen are generally referred to as ‘film musicals’ (Altman 1989; Altman 2004), to differentiate them from those staged in the theatre. However this definition is problematic because it can suggest that the musical component, which is an integral part of the art form, is subordinate in the narrative project. In this essay I argue that there was a change in the attitude to the music in the film musical over the years 1943 – 1964, a period in which the conventional Broadway musical underwent a radical transformation. In the late 1940s new productions tailed off significantly and producers focused on mounting revivals of the hits of the 1930s and early 1940s. At the same time the Broadway production system changed radically and the onus moved from Broadway to the Hollywood film industry (La Polla – Monteleone 2002; La Polla 2004). Rather than taking a rigidly classificatory approach or arriving at a de- finition of a genre – the musical – whose salient character has been its ongoing transformism, this essay hopes to contribute to a clearer vision of the film musical, based on the role music played in the passage from theatrical to cinematographic language. 2 Marida Rizzuti One Touch of Venus and My Fair Lady1 are two significant works in the history of the musical because they span the chosen period and represent the interchange that took place between Broadway and Holly- wood. -

Weill Program

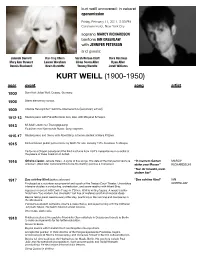

kurt weill uncovered: in cabaret operamission Friday, February 11, 2011, 8:00 PM Gershwin Hotel, New York City soprano MARCY RICHARDSON baritone IAN GREENLAW with JENNIFER PETERSON and guests: Janinah Burnett Hai-Ting Chinn Sarah Nelson Craft Dora Hastings Mary Ann Stewart Lauren Worsham Glenn Seven Allen Ryan Allen Dennis Blackwell Kevin Burdette Tommy Wazelle Jorell Williams KURT WEILL (1900-1950) year event song artist 1900 Born Kurt Julian Weill, Dessau, Germany. 1906 Starts elementary school. 1909 Attends Herzogliche Friedrichs-Oberrealschule [secondary school]. 1912-13 Studies piano with Franz Brückner and, later, with Margaret Schapiro 1913 Mi Addir: Jüdischer Trauungsgesang. Es blühen zwei flammende Rosen. Song fragment. 1915-17 Studies piano and theory with Albert Bing, a former student of Hans Pfitzner. 1915 Earliest known public performance by Weill: Für uns, January 1915, Dessauer Feldkorps. Performs a Chopin prelude and the third nocturne from Liszt’s Liebesträume in a recital at the palace of Duke Friedrich of Anhalt. 1916 Ofrahs Lieder, Jehuda Halevi. A cycle of five songs. The date of the first performance is “In meinem Garten MARCY unknown. (Weill later considered this to be his starting point as a composer.) stehn zwei Rosen” RICHARDSON “Nur dir fürwahr, mein stolzer Aar” 1917 Das schöne Kind (author unknown) “Das schöne Kind” IAN Employed as a volunteer accompanist and coach at the Dessau Court Theater. Undertakes GREENLAW intensive studies in conducting, orchestration, and score-reading with Albert Bing. Appears in concert with Emilie Feuge in Cöthen. Weill is writing fugues. A music teacher finds them “too modern, too chromatic” but free of mistakes and full of musical ideas. -

The Two Worlds of Kurt Weill." Morton Gould Comes Across Very Vividly in His Own Right, up Weill's and His Orchestra

1 for he "The Two Worlds of Kurt Weill." Morton Gould comes across very vividly in his own right, up Weill's and His Orchestra. RCA Victor LM 2863, $4.79 is highly articulate and cogent. He points (LP); LSC 2863, $5.79 (SD). theatrical perception in relating how the composer helped him (Nash was then new to the theatre) to grasp the values of quantity and stress when writing KURT WEILL'S music changed radically after he a lyric. Langston Hughes, discussing his collabora- left Europe and came to the United States. tion with Weill and Elmer Rice on Street Scene, pro- and under- What had once been lean, mordant. and dryly biting vides a revealing indication of the depth became, in his early efforts here, surprisingly bland standing of Weill's interest in the blues; he also and conventional. Once Weill had assimilated presents an amusing sidelight on Rice. American convention, he made his points not only In both cases, one gets considerably more from reading by matching the best of American theatrical com- the personal narration than one might from inflec- posers with September Song, but by breaking the same words in print. There are shadings, through American convention with his score to tions, touches of humor, stresses of sincerity that views Lady in the Dark. Morton Gould's collection of are revealing both of the speakers and of their with Weill's songs recognizes the two aspects of his mu- of Weill. The dangers of a Living Liner arise to say sical career by devoting one side of the disc to his personalities who have something interesting As a result.