One Touch of Venus Volume 28 in This Issue Kurt Weill Number 1 Newsletter Spring 2010 Note from the Editor 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG SCRIPT LIBRARY Nov 2013.Xlsx

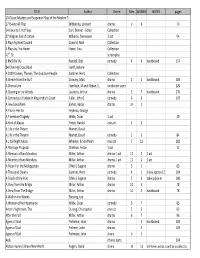

TITLE Author Genre Men WOMEN NOTES pages 10 Classic Mystery and Suspense Plays of the Modern T 1776‐And All That Wibberley, Leonard drama 98 70 24 Favorite 1 Act Plays Cerf, Bennet ‐ Editor Collection 27 Wagons Full of Cotton Williams, Tennessee 1 act 54 3 Plays by Noel Coward Coward, Noel Collection 3 Plays by Tina Howe Howe, Tina Collection 42nd St. screenplay 6 RMS RIV VU Randall, Bob comedy 4 4 hardbound 157 84 Charring Cross Road Hanff, Helene A 1000 Clowns, Thieves, The Goodbye People Gardner, Herb Collection A Breeze from the Gulf Crowley, Mart drama 2 1 hardbound 184 A Chorus Line Hamlisch, M.and Kleban, E, . conductor score 220 A Clearing in the Woods Laurents, Arthur drama 5 5 hardbound 170 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Fuller, John G. comedy 6 6 147 A Few Good Men Sorkin, Aaron drama 14 1 A Flea in Her Ear Feydeau, George A Florentine Tragedy Wilde, Oscar 1 act 20 A Kind of Alaska Pinter, Harold one act 1 2 A Life in the Theare Mamet, David A Life in the Theatre Mamet, David comedy 2 0 84 A Little Night Music Wheeler, & Sondheim musical 7 11 182 A Marriage Proposal Chekhov, Anton 1 act 12 A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Moon For the Misbegotten O'Neill, Eugene drama 3 1 83 A Thousand Clowns Gardner, Herb comedy 4 1 1 boy approx 12 104 A Touch of the Poet O'Neill, Eugene drama 7 3 takes place in 180 A View from the Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 78 A View From The Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 hardbound 78 A Walk -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

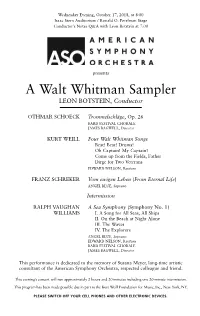

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Note Al Programma

NOTE AL PROGRAMMA Berlino, al centro del continente europeo e della sua storia, è sempre stata in grado di rivelare, in ogni epoca, da che parte spirasse il vento, rappresentando il fulcro della modernità occidentale quanto ad arte, musica, cultura e pensiero politico. Agli inizi degli Anni Trenta del secolo scorso l’aria che tirava era fortemente condizionata dal Nazismo. La crisi economica derivante dal crollo di Wall Street nel ’29 e la disoccupazione dilagante nella Repubblica di Weimar avevano posto le basi a un cambiamento politico che, per una città così vitale e aperta alla diversità e ai dibattiti d’ogni tendenza, rappresentava una grossa stonatura. Dal disagio sociale i nazisti avevano tratto beneficio e potere, e inculcarono nel pensiero comune che le colpe di quel dissesto fossero da imputare alla popolazione di discendenza ebraica. E l’incolpare gli ebrei di ogni fatto qualunque, perfino meteorologico, divenne per tutti un luogo comune. La devastazione, nel novembre del ’38, delle vetrine dei negozi appartenenti a commercianti ebrei fu la prova di una strada ormai segnata e senza ritorno. Mentre una legge stabiliva che quei danni dovessero «essere immediatamente riparati [dagli stessi] titolari e dai dirigenti ebrei [e a loro spese]», in città v’era uno spazio in cui tutto questo, oltre al quotidiano, diventava materia di un discorso comune, capace di cogliere l’ironia da ogni fatto rovesciando l’umore di ciascun cittadino: era il cabaret. Esisteva da tempo, il cabaret, come palcoscenico irriverente e beffardo sull’attualità. Ma nel periodo nazista questo divenne inevitabilmente il nucleo di grandi contraddizioni e di conflitti ideologici. -

Der Kuhhandel

Volume 22 Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Der Kuhhandel In this Issue: Bregenz Festival Reviewed Feature Article about Weill and An Operetta Resurfaces Operetta Volume 22 In this issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 2004 Note from the Editor 3 Letters 3 ISSN 0899-6407 Bregenz Festival © 2004 Kurt Weill Foundation for Music Der Protagonist / Royal Palace 4 7 East 20th Street Horst Koegler New York, NY 10003-1106 Der Kuhhandel 6 tel. (212) 505-5240 Larry L. Lash fax (212) 353-9663 Zaubernacht 8 Horst Koegler Published twice a year, the Kurt Weill Newsletter features articles and reviews (books, performances, recordings) that center on Kurt Weill but take a broader look at issues of twentieth-century music Feature and theater. With a print run of 5,000 copies, the Newsletter is dis- Weill, the Operettenkrise, and the tributed worldwide. Subscriptions are free. The editor welcomes Offenbach Renaissance 9 the submission of articles, reviews, and news items for inclusion in Joel Galand future issues. A variety of opinions are expressed in the Newsletter; they do not Books necessarily represent the publisher's official viewpoint. Letters to the editor are welcome. Dialog der Künste: Die Zusammenarbeit von Kurt Weill und Yvan Goll 16 by Ricarda Wackers Esbjörn Nyström Staff Elmar Juchem, Editor Carolyn Weber, Associate Editor Performances Dave Stein, Associate Editor Teva Kukan, Production Here Lies Jenny in New York 18 William V. Madison Kurt Weill Foundation Trustees Kim Kowalke, President Paul Epstein Der Zar lässt sich photographieren -

An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2011 An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill Elizabeth Rose Williamson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Williamson, Elizabeth Rose, "An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill" (2011). Honors Theses. 2157. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2157 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND MUSICAL ADAPTATION IN VOCAL COMPOSITIONS OF KURT WEILL by Elizabeth Rose Williamson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2011 Approved by Reader: Professor Corina Petrescu Reader: Professor Charles Gates I T46S 2^1 © 2007 Elizabeth Rose Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people of the Kurt Weill Zentrum in Dessau Gennany who graciously worked with me despite the reconstruction in the facility. They opened their resources to me and were willing to answer any and all questions. Thanks to Clay Terry, I was able to have an uproariously hilarious ending number to my recital with “Song of the Rhineland.” I thank Dr. Charles Gates for his attention and interest in my work. -

RIVER ROAD MOSES CEMETERY: a Historic Preservation Evaluation

Gibson Grove Cemetery, Montgomery County THE RIVER ROAD MOSES CEMETERY: A Historic Preservation Evaluation Report prepared for the River Road African American community descendants David S. Rotenstein, PhD Silver Spring, Maryland September 2018 [email protected] (404) 326-9244 Management Summary This report presents research on the River Road Moses Cemetery site in Bethesda, Maryland. It was prepared on behalf of the River Road African American descendant community. The following sections include a historic context divided into periods developed by the Maryland Historical Trust for the evaluation of historic properties. The historic context presents substantive archival and oral history research documenting the cemetery site, the community within which it is located, the fraternal organization that founded it, and its historical connections to Washington, D.C. The historic context is used as a baseline to evaluate the property against the Montgomery County criteria for designation in the Master Plan for Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places. This report finds that the River Road Moses Cemetery appears to be eligible for designation in the Montgomery County Master Plan for Historic Preservation under four criteria: for its associations with the development of Montgomery County and the region; because it exemplifies multiple aspects of Montgomery County’s heritage; because it embodies distinctive characteristics typical of its historic property type; and, because it represents a distinguishable entity within a cultural landscape. The River Road Moses Cemetery furthermore appears to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places under three criteria. The site appears to be eligible for listing under Criterion A for its associations with African American and suburban history; Criterion C for its architectural and landscape qualities; and, Criterion D for its potential to yield significant new information in history. -

Amalie Joachim's 1892 American Tour

Volume XXXV, Number 1 Spring 2017 Amalie Joachim’s 1892 American Tour By the 1890s, American audiences had grown accustomed to the tours of major European artists, and the successes of Jenny Lind and Anton Rubinstein created high expectations for the performers who came after them. Amalie Joachim toured from March to May of 1892, during the same months as Paderewski, Edward Lloyd, and George and Lillian Henschel.1 Although scholars have explored the tours of artists such as Hans von Bülow and Rubinstein, Joachim’s tour has gone largely unnoticed. Beatrix Borchard, Joachim’s biographer, has used privately held family letters to chronicle some of Joachim’s own responses to the tour, as well as a sampling of the reviews of the performer’s New York appearances. She does not provide complete details of Joachim’s itinerary, however, or performances outside of New York. Although Borchard notes that Villa Whitney White traveled with Joachim and that the two performed duets, she did not realize that White was an American student of Joachim who significantly influenced the tour.2 The women’s activities, however, can be traced through reviews and advertisements in newspapers and music journals, as well as brief descriptions in college yearbooks. These sources include the places Joachim performed, her repertoire, and descriptions of the condition of her voice and health. Most of Joachim’s performances were in and around Boston. During some of her time in this city, she stayed with her Amalie Joachim, portrait given to Clara Kathleen Rogers. friend, the former opera singer Clara Kathleen Rogers. -

Street Scene

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene A Study Guide prepared by VIRGINIA OPERA 1 Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of World Premiere 3 Cast of Characters 3 Musical numbers 4 Brief plot summary 5 Full plot synopsis with musical examples 5 Historical background 12 The creation of the opera 13 Relevance of social themes in 21st century America 15 Notable features of musical style 16 Discussion questions 19 3 STREET SCENE AN AMERICAN OPERA Music by KURT WEILL Book by ELMER RICE, adapted from his play of the same name Lyrics by LANGSTON HUGHES Premiere First performance on January 9, 1947 at the Adelphi Theater in New York City Setting The action takes place outside a tenement house in New York City on an evening in June 1946. -

News and Events

Volume 15 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 1997 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news &news events The Royal National Theatre Ushers in Lady in the Dark &news events Opening Catherine Ashmore (right). Catherine Ashmore Scenes (left), Damm Photos: Van Then and Now . Gertrude Lawrence as Liza in 1941 Maria Friedman as Liza in 1997 (with Richard Hale). (with Hugh Ross). The production by Francesca Zambello is stylish, The show is original and appealing and, as heroines go, so is Maria Friedman. Her Liza Elliott stalks into her restrained, cerebral. Weill’s music is plangent and shrink’s eyrie radiating nervy, brittle assurance, then sinuous, a remarkable synthesis of Weimar jazz and spins rapturously off into the first of the dream- pre-Sondheim querulousness. Maria Friedman, sure- sequences that interrupt the more realistic proceed- ly confirmed now as our supreme musical actress, ings. Our own Tina Brown would have to be promot- negotiates her backward spiral with exuberant grace ed from the chair of the New Yorker to the throne of and wit, swirling in mists and ballgowns, defiantly zip- England to match a fantasy like that. ping on the Schiaparelli frock when she takes off with — Benedict Nightingale, “Freudian drama that does not a movie star hunk (the Victor Mature role is occupied shrink from emotion,” The Times (12 March 1997) by a suitably anaemic grinner, Steven Edward Moore) and even stepping daintily across a tightrope, in Adrianne Lobel has designed a conceptual setting of sail-like Stoppardian vein, to prove she is a “proponent of triangles which introduces a number of staging constraints. -

A Performer's Guide to the American Theater Songs of Kurt Weill

A Performer's Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Morales, Robin Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:09:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194115 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATER SONGS OF KURT WEILL (1900-1950) by Robin Lee Morales ________________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As member of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read document prepared by Robin Lee Morales entitled A Performer’s Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Faye L. Robinson_________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Edmund V. Grayson Hirst__________________ Date: May 5, 2008 John T. Brobeck _________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

The Presideut's Column

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY THE KURT WEILL FOUNDATION FOR MUSIC HENRY MARX, EDITOR FALL 1983 lishers and vendors throughout the world. performances, recordings, productions, he Presideut's My own research and performing ac workshops, fellowships, and scholar Column: tivities had to be suspended while I ships. Already the Foundation staff of doggedly learned about international Mrs. Symonette and Mr. Farneth, with the A PROFILE OF copyright laws, terminations, extensions, aid of a half-time secretary, are answering T the differences between small, grand inquiries and assisting scholars, perform THE FOUNDATION and print rights, performing rights so ers, conductors, and producers with vari It's hard for me to believe that Lenya has cieties, and the curious internal mecha ous projects. Now that the Foundation's been gone nearly two years. When she nisms of the "publishing" industry existence is secure and its role defined, asked me to succeed her as President of wherein few "publishers" actually print we are entering an exciting new phase of the Foundation, I had no inkling that music anymore. My naivete was neces activities. This is the first issue of a sem, these two years would be the most hec sarily short-lived as I reviewed contracts annual newsletter; 1984 will witness the tic. frustrating, rewarding and exhilarating and accounts that apparently had never publication of Volume I of a Weill Year of my life. Although it had been chartered been verified, much less audited. I would book; long-term plans are being formu nearly twenty years ago and had been hope that soon it will no longer be impos lated for publication, performance, or active sporadically during those two de sible to purchase or rent certain scores in recording of such "lost'' works as Der cades, the Foundation had been little this country because the U.S.