University of Copenhagen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT for DISTRIBUTION Part I

CONTENTS List of Figures xiii List of Tables xvii Preface xix The Inevitable Note on Orthography xxiii Acknowledgments xxv PART I. CULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIves 3 1 COPYRIGHTEDINTRODUCTION: THE ITZA MAYAS MATERIAL AND THE PETÉN ITZA MAYAS, THEIR ENVIRONMENTS AND THEIR NEIGHBORS NOTPrudence FOR M. Rice DISTRIBUTIONand Don S. Rice 5 The Maya Lowlands: Environmental Perspectives 5 Who Were the Itzas? Etymological Perspectives 8 The Itzas of Petén 11 The Itzas of the Northern Lowlands and Their Allies 22 2 ITZAJ MAYA FROM A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Charles Andrew Hofling 28 Yukateko versus Southern Yukatekan Language Varieties 31 Itzaj and Mopan 35 vii viii Contents Contact with Ch'olan Languages 35 Concluding Discussion 38 3 THE LAKE PETÉN ITZÁ WATERSHED: MODERN AND HISTORICAL ECOLOGY Mark Brenner 40 Geology and Modern Ecology 40 Modern Limnology 42 Lacustrine Flora and Fauna 45 Historical Ecology 46 Climate Change 50 Summary 53 PART II. THEORETicAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EpicLASSic ITZAS: FACTIONS, MIGRATIONS, ORIGINS, AND TEXTs 55 4 THEORETICAL CONTEXTS Prudence M. Rice 59 Migration: Travel Tropes and Mobility Memes 59 Identities 65 Factions and Factionalism 67 Spatiality 70 5 ITZA ORIGINS: TEXTS, MYTHS, LEGENDS Prudence M. Rice 77 The Books of theChilam Balam 79 Some Previous Reconstructions of Itza Origins 88 COPYRIGHTEDConcluding Thoughts 93 MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION 6 LOWLAND MAYA EpiCLASSIC MIGRATIONS Prudence M. Rice 97 Western Lowlands 98 Southwestern Petén 101 Central Petén Lakes Region 102 Eastern Petén, Belize, and the Southeast 105 Northern Lowlands 106 Rethinking Epiclassic Migrations and the Itzas 109 Contents ix 7 EpiCLASSIC MATERIAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE ITZAS Prudence M. -

Polities and Places: Tracing the Toponyms of the Snake Dynasty

Polities and Places: Tracingthe Toponymsof the Snake Dynasty SIMON MARTIN University of Pennsylvania Museum ERIK VELÁSQUEZ GARCÍA Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México One of the more intriguing and important topics to thonous ones that had at some point transferred their emerge in Maya studies of recent years has been the his- capitals or splintered, each faction laying claim to the tory of the “Snake” dynasty. Research over the past two same title. The landscape of the Classic Maya proves decades has identified mentions of its kings across the to have been a volatile one, not simply in the dynamic length and breadth of the lowlands and produced evi- interactions and imbalances of power between polities, dence that they were potent political players for almost but in the way the polities themselves were shaped by two centuries, spanning the Early Classic to Late Classic historical forces through time. periods.1 Yet this data has implications that go beyond a single case study and can be used to address issues of general relevance to Classic Maya politics. In this brief Placing Calakmul paper we use them to further explore the meaning of The distinctive Snake emblem glyphs and their connection to polities and emblem glyph is ex- places. pressed in full as K’UH- The significance of emblem glyphs—whether they ka-KAAN-la-AJAW or are indicative of cities, deities, domains, polities, or k’uhul kaanul ajaw (Fig- dynasties—has been debated since their discovery ure 1).3 It first came to (Berlin 1958). The recognition of their role as the scholarly notice as one personal epithets of kings based on the title ajaw “lord, of the “four capitals” ruler” (Lounsbury 1973) was the essential first step to listed on Copan Stela A, comprehension (Mathews and Justeson 1984; Mathews a set of cardinally affili- Figure 1. -

The Terminal Classic Period at Ceibal and in the Maya Lowlands

THE TERMINAL CLASSIC PERIOD AT CEIBAL AND IN THE MAYA LOWLANDS Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan University of Arizona Ceibal is well known for the pioneering investigations conducted by Harvard University in the 1960s (Sabloff 1975; Smith 1982; Tourtellot 1988; Willey 1990). Since then, Ceibal has been considered to be a key site in the study of the Classic Maya collapse (Sabloff 1973a, 1973b; Sabloff and Willey 1967). The results of this project led scholars to hypothesize the following: 1) Ceibal survived substantially longer than other centers through the period of the Maya collapse; and 2) the new styles of monuments and new types of ceramics resulted from foreign invasions, which contributed to the Maya collapse. In 2005 we decided to revisit this important site to re-examine these questions in the light of recent developments in Maya archaeology and epigraphy. The results of the new research help us to shape a more refined understanding of the political process during the Terminal Classic period. The important points that we would like to emphasize in this paper are: 1) Ceibal did not simply survive through this turbulent period, but it also experienced political disruptions like many other centers; 2) this period of political disruptions was followed by a revival of Ceibal; and 3) our data support the more recent view that there were no foreign invasions; instead the residents of Ceibal were reorganizing and expanding their inter-regional networks of interaction. Ceibal is located on the Pasión River, and a comparison with the nearby Petexbatun centers, including Dos Pilas and Aguateca, is suggestive. -

The Investigation of Classic Period Maya Warfare at Caracol, Belice

The Investigation of Classic Period Maya Warfare at Caracol, Belice ARLEN F. CHASE DIANE Z. CHASE University of Central Florida Prior to the 1950s the prevalent view of the like rulers who were concerned whith preserving ancient Maya was as a peaceful people. ln 1952, their histories in hieroglyphic texts on stone and Robert Rands completed his Ph. D. thesis on the stucco; investigations at the site have thus far evidences of warfare in Classic Maya art, following uncovered some 40 carved monuments (Beetz and up on the important work just completed by Tatia- Satterthwaite 1981; A. Chase and D. Chase na Proskouriakoff (1950). Since then, research has 1987b). Caracol is unusual, however, in having rapidly accumulated substantial documentation left us written records that it successfully waged that the Maya were in fact warlike (cf. Marcus warfare against two of its neighboring polities at 1974; Repetto Tio 1985). There is now evidence different times within the early part of the Late for the existence of wars between major political Classic Period. units in the Maya area and, importantly, Maya There are two wars documented in the hiero- kingship has also been shown to be inextricably glyphic texts: Caracol defeats Tikal in 9.6.8.4.2 or joined with concepts of war, captives, and sacrifice A. D. 562 (A. Chase and D. Chase 1987a:6, (Demarest 1978; Schele and Miller 1986; Freidel 1987b:33,60; S. Houston in press) and Naranjo in 1986). Warfare also has been utilized as a power- 9.9.18.16.3 or A. D. 631 (Sosa and Reents 1980). -

Late Classic Maya Political Structure, Polity Size, and Warfare Arenas

LATE CLASSIC MAYA POLITICAL STRUCTURE, POLITY SIZE, AND WARFARE ARENAS Arlen F. CHASE and Diane Z. CHASE Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Central Florida Studies of the ancient Maya have moved forward at an exceedingly rapid rate. New sites have been discovered and long-term excavations in a series of sites and regions have provided a substantial data base for interpreting ancient Maya civili- zation. New hieroglyphic texts have been found and greater numbers of texts can be read. These data have amplified our understanding of the relationships among subsistence systems, economy, and settlement to such an extent that ancient Maya social and political organization can no longer be viewed as a simple dichoto- mous priest-peasant (elite-commoner) model. Likewise, monumental Maya archi- tecture is no longer viewed as being indicative of an unoccupied ceremonial center, but rather is seen as the locus of substantial economic and political activity. In spite of these advances, substantial discussion still exists concerning the size of Maya polities, whether these polities were centralized or uncentralized, and over the kinds of secular interactions that existed among them. This is espe- cially evident in studies of aggression among Maya political units. The Maya are no longer considered a peaceful people; however, among some modern Maya scholars, the idea still exists that the Maya did not practice real war, that there was little destruction associated with military activity, and that there were no spoils of economic consequence. Instead, the Maya elite are portrayed as engaging predo- minantly in raids or ritual battles (Freidel 1986; Schele and Mathews 1991). -

El Proceso De Desarrollo Político Del Estado Maya De Yaxhá: Un Caso De Competencia De Élites Y Readecuación Dentro De Un Marco De Circunscripción Territorial

El proceso de desarrollo político del estado maya de Yaxhá: un caso de competencia de élites y readecuación dentro de un marco de circunscripción territorial Vilma Fialko DECORSIAP-Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes Introducción La información contenida en este documento es representativa de la región noreste de Petén, Guatemala. Durante 19 años el Departamento de Conservación y Rescate de Sitios Arqueológicos Prehispánicos (DECORSIAP), antes conocido como PRONAT-PROSIAPETEN, del Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala, ha realizado estudios regionales sistemáticos en el centro y las periferias de los sitios mayores de Tikal, Yaxhá, Nakum y Naranjo-Sa’al (Figura 1). Las investigaciones arqueológicas han permitido determinar asentamientos con jerarquías de cuatro niveles, descritos en el presente estudio como centros mayores, centros intermedios, centros menores y centros residenciales/rurales (Fialko 1996b, 1997; Fialko et al. 2005), lo que ha permitido determinar aspectos de territorialidad, geografía política y distribución de asentamientos según contextos ambientales (Figura 2). Los reconocimientos prosiguen efectuándose a nivel de cobertura total, y también mediante muestreo con transectos de larga distancia, cada uno de ellos promediando los 21 km y de manera dirigida a lo largo y entorno de cuencas hídricas y lacustres. Aún están en proceso los mapeos sistemáticos de todos los grupos residenciales y sitios arqueológicos identificados. Los procedimientos de recopilación de -

Foundation for Maya Cultural and Natural Heritage

Our mission is to coordinate efforts Foundation for Maya Cultural and provide resources to identify, and Natural Heritage lead, and promote projects that protect and maintain the cultural Fundación Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya and natural heritage of Guatemala. 2 # nombre de sección “What is in play is immense” HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco he Maya Biosphere Reserve is located in the heart of the Selva Maya, the Maya Jungle. It is an ecological treasure that covers one fifth of Guatemala’s landmass (21,602 Tsquare kilometers). Much of the area remains intact. It was established to preserve—for present and future generations— one of the most spectacular areas of natural and cultural heritage in the world. The Maya Biosphere Reserve is Guatemala’s last stronghold for large-bodied, wide-ranging endangered species, including the jaguar, puma, tapir, and black howler monkey. It also holds the highest concentration of Maya ruins. Clockwise from bottomleft José Pivaral (President of Pacunam), Prince Albert II of Monaco (sponsor), Mel Gibson (sponsor), Richard Hansen (Director of Mirador The year 2012 marks the emblematic change of an era in the ancient calendar of the Maya. This Archaeological Project) at El Mirador momentous event has sparked global interest in environmental and cultural issues in Guatemala. After decades of hard work by archaeologists, environmentalists, biologists, epigraphers, and other scientists dedicated to understanding the ancient Maya civilization, the eyes of the whole Pacunam Overview and Objectives 2 world are now focused on our country. Maya Biosphere Reserve 4 This provides us with an unprecedented opportunity to share with the world our pressing cause: Why is it important? the Maya Biosphere Reserve is in great danger. -

Who Were the Maya? by Robert Sharer

Who Were the Maya? BY ROBERT SHARER he ancient maya created one of the Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador until the Spanish Conquest. world’s most brilliant and successful The brutal subjugation of the Maya people by the Spanish ca. 1470 CE civilizations. But 500 years ago, after the extinguished a series of independent Maya states with roots The Kaqchikel Maya establish a new Spaniards “discovered” the Maya, many as far back as 1000 BCE. Over the following 2,500 years scores highland kingdom with a capital at Iximche. could not believe that Native Americans of Maya polities rose and fell, some larger and more powerful had developed cities, writing, art, and than others. Most of these kingdoms existed for hundreds of ca. 1185–1204 CE otherT hallmarks of civilization. Consequently, 16th century years; a few endured for a thousand years or more. K’atun 8 Ajaw Europeans readily accepted the myth that the Maya and other To understand and follow this long development, Maya Founding of the city of Mayapan. indigenous civilizations were transplanted to the Americas by civilization is divided into three periods: the Preclassic, the “lost” Old World migrations before 1492. Of course archaeol- Classic, and the Postclassic. The Preclassic includes the ori- ogy has found no evidence to suggest that Old World intru- gins and apogee of the first Maya kingdoms from about 1000 sions brought civilization to the Maya or to any other Pre- BCE to 250 CE. The Early Preclassic (ca. 2000–1000 BCE) Columbian society. In fact, the evidence clearly shows that pre-dates the rise of the first kingdoms, so the span that civilization evolved in the Americas due to the efforts of the began by ca. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XVI, No. 2

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Ancient Cultures Institute Volume XVI, No. 2, Fall 2015 In This Issue: For Love of the Game: For Love of the The Ballplayer Panels of Tipan Chen Uitz Game: The Ballplayer Panels of in Light of Late Classic Athletic Hegemony Tipan Chen Uitz in Light of Late Classic CHRISTOPHE HELMKE Athletic Hegemony University of Copenhagen by CHRISTOPHER R. ANDRES Christophe Helmke Michigan State University Christopher R. Andres Shawn G. Morton and SHAWN G. MORTON University of Calgary Gabriel D. Wrobel PAGES 1-30 GABRIEL D. WROBEL Michigan State University • The Maya Goddess One of the principal motifs of ancient Maya ballplayers are found preferentially at of Painting, iconography concerns the ballgame that sites that show some kind of interconnec- Writing, and was practiced both locally and through- tion and a greater degree of affinity to the Decorated Textiles out Mesoamerica. The pervasiveness of kings of the Snake-head dynasty that had ballgame iconography in the Maya area its seat at Calakmul in the Late Classic (see by has been recognized for some time and Martin 2005). This then is the idea that is Timothy W. Knowlton has been the subject of several pioneering proposed in this paper, and by reviewing PAGES 31-41 and insightful studies, including those some salient examples from a selection • of Stephen Houston (1983), Linda Schele of sites in the Maya lowlands, we hope The Further and Mary Miller (1986:241-264), Nicholas to make it clear that the commemoration Adventures of Merle Hellmuth (1987), Mary Miller and Stephen of ballgame engagements wherein local (continued) Houston (1987; see also Miller 1989), rulers confront their overlord are charac- by Marvin Cohodas (1991), Linda Schele and teristic of the political rhetoric that was Merle Greene David Freidel (1991; see also Freidel et al. -

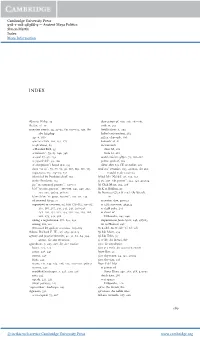

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

Descargar Este Artículo En Formato

Corzo, Lilian A., Marco Tulio Alvarado y Juan Pedro Laporte 1998 Ucanal: Un sitio asociado a la cuenca media del río Mopan. En XI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1997 (editado por J.P. Laporte y H. Escobedo), pp.209-235. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (versión digital). 16 UCANAL: UN SITIO ASOCIADO A LA CUENCA MEDIA DEL RÍO MOPAN Lilian A. Corzo Marco Tulio Alvarado Juan Pedro Laporte El río Mopan nace en las montañas del municipio de Dolores, fluye de sur a norte hasta resumirse en el área denominada Campuc; esa sección es la cuenca alta del río (Figura 1). Este resurge a 12 km al norte; el nuevo caudal, conocido como Xilinte, recorre otros 15 km hasta unirse con el río Santo Domingo; desde este punto, el río es navegable. Esta es parte de la cuenca media del río Mopan y se extiende por otros 15 km hacia el norte. En general, el territorio abarca 400 km², limitado al oeste por la cuenca Salsipuedes y al este por la Chiquibul. Esta zona tiene una altura entre 260 y 300 m SNM, con reducidas y dispersas elevaciones mayores. Los niveles inferiores corresponden a la planicie de inundación del río, muy rica para los cultivos, mientras que el asentamiento prehispánico generalmente se localiza en los terrenos más elevados. En ello es importante la formación de terrazas de aluvión. El río tiene una marcada dirección hacia el norte, aunque son abundantes los meandros. La cuenca media del río Mopan abarca unos 24 km norte-sur y 18 km este-oeste.