Laboratory Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8: Gravimetric Methods

Chapter 8 Gravimetric Methods Chapter Overview 8A Overview of Gravimetric Methods 8B Precipitation Gravimetry 8C Volatilization Gravimetry 8D Particulate Gravimetry 8E Key Terms 8F Chapter Summary 8G Problems 8H Solutions to Practice Exercises Gravimetry includes all analytical methods in which the analytical signal is a measurement of mass or a change in mass. When you step on a scale after exercising you are making, in a sense, a gravimetric determination of your mass. Mass is the most fundamental of all analytical measurements, and gravimetry is unquestionably our oldest quantitative analytical technique. The publication in 1540 of Vannoccio Biringuccio’sPirotechnia is an early example of applying gravimetry—although not yet known by this name—to the analysis of metals and ores.1 Although gravimetry no longer is the most important analytical method, it continues to find use in specialized applications. 1 Smith, C. S.; Gnodi, M. T. translation of Biringuccio, V. Pirotechnia, MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1959. 355 356 Analytical Chemistry 2.0 8A Overview of Gravimetric Methods Before we consider specific gravimetric methods, let’s take a moment to develop a broad survey of gravimetry. Later, as you read through the de- scriptions of specific gravimetric methods, this survey will help you focus on their similarities instead of their differences. You will find that it is easier to understand a new analytical method when you can see its relationship to other similar methods. 8A.1 Using Mass as an Analytical Signal Method 2540D in Standard Methods for Suppose you are to determine the total suspended solids in the water re- the Examination of Waters and Wastewaters, leased by a sewage-treatment facility. -

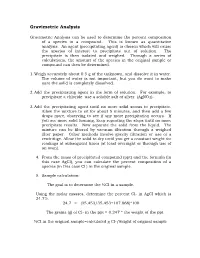

Gravimetric Analysis

Gravimetric Analysis Gravimetric Analysis can be used to determine the percent composition of a species in a compound. This is known as quantitative analysis. An agent (precipitating agent) is chosen which will cause the species of interest to precipitate out of solution. The precipitate is then isolated and weighed. Through a series of calculations, the amount of the species in the original sample or compound can then be determined. 1. Weigh accurately about 0.5 g of the unknown, and dissolve it in water. The volume of water is not important, but you do want to make sure the solid is completely dissolved. 2. Add the precipitating agent in the form of solution. For example, to precipitate a chloride use a soluble salt of silver (AgNO3). 3. Add the precipitating agent until no more solid seems to precipitate. Allow the mixture to sit for about 5 minutes, and then add a few drops more, observing to see if any more precipitation occurs. If you see more solid forming, keep repeating the steps until no more precipitate results. Now separate the solid from the liquid. The mixture can be filtered by vacuum filtration through a weighed filter paper. Other methods involve gravity filtration or use of a centrifuge. Allow the solid to dry until you get a constant weight for readings at subsequent times (at least overnight or through use of an oven). 4. From the mass of precipitated compound (ppt) and the formula (in this case AgCl), you can calculate the percent composition of a species (in this case Cl-) in the original sample. -

1 Abietic Acid R Abrasive Silica for Polishing DR Acenaphthene M (LC

1 abietic acid R abrasive silica for polishing DR acenaphthene M (LC) acenaphthene quinone R acenaphthylene R acetal (see 1,1-diethoxyethane) acetaldehyde M (FC) acetaldehyde-d (CH3CDO) R acetaldehyde dimethyl acetal CH acetaldoxime R acetamide M (LC) acetamidinium chloride R acetamidoacrylic acid 2- NB acetamidobenzaldehyde p- R acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride 4- R acetamidodeoxythioglucopyranose triacetate 2- -2- -1- -β-D- 3,4,6- AB acetamidomethylthiazole 2- -4- PB acetanilide M (LC) acetazolamide R acetdimethylamide see dimethylacetamide, N,N- acethydrazide R acetic acid M (solv) acetic anhydride M (FC) acetmethylamide see methylacetamide, N- acetoacetamide R acetoacetanilide R acetoacetic acid, lithium salt R acetobromoglucose -α-D- NB acetohydroxamic acid R acetoin R acetol (hydroxyacetone) R acetonaphthalide (α)R acetone M (solv) acetone ,A.R. M (solv) acetone-d6 RM acetone cyanohydrin R acetonedicarboxylic acid ,dimethyl ester R acetonedicarboxylic acid -1,3- R acetone dimethyl acetal see dimethoxypropane 2,2- acetonitrile M (solv) acetonitrile-d3 RM acetonylacetone see hexanedione 2,5- acetonylbenzylhydroxycoumarin (3-(α- -4- R acetophenone M (LC) acetophenone oxime R acetophenone trimethylsilyl enol ether see phenyltrimethylsilyl... acetoxyacetone (oxopropyl acetate 2-) R acetoxybenzoic acid 4- DS acetoxynaphthoic acid 6- -2- R 2 acetylacetaldehyde dimethylacetal R acetylacetone (pentanedione -2,4-) M (C) acetylbenzonitrile p- R acetylbiphenyl 4- see phenylacetophenone, p- acetyl bromide M (FC) acetylbromothiophene 2- -5- -

United States Patent to 11 4,012,839 Hill 45 Mar

United States Patent to 11 4,012,839 Hill 45 Mar. 22, 1977 (54) METHOD AND COMPOSITION FOR TREATING TEETH OTHER PUBLICATIONS 75) Inventor: William H. Hill, St. Paul, Minn. Dental Abstracts, "Silver Nitrate Treatment of Proxi (73) Assignee: Peter Strong & Company, Inc., mal Caries in Primary Molars', p. 272, May 1957. Portchester, N.Y. Primary Examiner-Robert Peshock (22 Filed: Nov. 26, 1973 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Thomas M. Meshbesher (21) Appl. No.: 418,997 57 ABSTRACT 52 U.S. Cl. ................................... 32/15; 424/129; In the well-known technique of disinfecting caries 424/210 infected or potentially caries-infected dental tissue with 51 int. Cl”.......................................... A61K 5/02 silver nitrate, silver thiocyanate or its complexes have 58 Field of Search ............ 424/290, 132, 129, 49, been substituted for silver nitrate with excellent disin 424/54; 32/15 fecting results and lowered side effects, e.g., with low 56) References Cited ered toxicity toward dental tissues and mouth mem UNITED STATES PATENTS branes and less blackening of exposed portions of the teeth. 1,740,543 12/1929 Gerngross .......................... 424/129 2,981,640 4/1961 Hill ................................. 171138.5 3,421,222 1/1969 Newman ................................ 32/15 16 Claims, No Drawings 4,012,839 1 2 and potassium or barium thiocyanate as a relatively METHOD AND COMPOSITION FOR TREATING non-irritating disinfectant is disclosed. TEETH Silver thiocyanate (AgSCN) is known to be both bactericidal and relatively light stable; see U.S. Pat. No. FIELD OF THE INVENTION 2,981,640 (Hill), issued Apr. 25, 1961. The Hill patent This invention relates to a method for treating mam teaches the use of AgSCN or mixtures thereof with malian dental tissue with a bactericidal amount of a other thiocyanates to treat or sterilize cloth articles silver salt. -

Lecture 10. Analytical Chemistry What Is Analytical Chemistry ?

5/5/2019 What is Analytical Chemistry ? It deals with: Lecture 10. • separation Analytical Chemistry • identification • determination of components in a sample. Basic concepts It includes coverage of chemical equilibrium and statistical treatment of data. It encompasses any type of tests that provide information relating to the chemical composition of a sample. 1 2 • Analytical chemistry is divided into two areas of analysis: • The substance to be analyzed within a sample • Qualitative – recognizes the particles which are present in a sample. is known as an analyte, whereas the substances which may cause incorrect or • Quantitative – identifies how much of inaccurate results are known as chemical particles is present in a sample. interferents. 3 4 1 5/5/2019 Qualitative analysis is used to separate an analyte from interferents existing in a sample and detect the previous one. It gives negative, positive, or yes/no types of data. Qualitative analysis It informs whether or not the analyte is present in a sample. 5 6 Examples of qualitative analysis 7 8 2 5/5/2019 Analysis of an inorganic sample The classical procedure for systematic analysis of an inorganic sample consists of several parts: preliminary tests (heating, solubility in water, appearance of moisture) more complicated tests e.g. introducing the sample into a flame and noting the colour produced; determination of anionic or cationic constituents of 9 solute dissolved in water 10 Flame test Sodium Bright yellow (intense, persistent) Potassium Pale violet (slight, fleeting) Solutions of ions, when mixed with concentrated Calcium Brick red (medium, fleeting) HCl and heated on a nickel/chromium wire in a flame, cause the flame to change to a colour Strontium Crimson (medium) characteristic of the element. -

1 Introduction of Mass Spectrometry and Ambient Ionization Techniques

1 1 Introduction of Mass Spectrometry and Ambient Ionization Techniques Yiyang Dong, Jiahui Liu, and Tianyang Guo College of Life Science & Technology, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, No. 15 Beisanhuan East Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100029, China 1.1 Evolution of Analytical Chemistry and Its Challenges in the Twenty-First Century The Chemical Revolution began in the eighteenth century, with the work of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794) representing a fundamental watershed that separated the “modern chemistry” era from the “protochemistry” era (Figure 1.1). However, analytical chemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, is an ancient science and its metrological tools, basic applications, and analytical processes can be dated back to early recorded history [1]. In chronological spans covering ancient times, the middle ages, the era of the nineteenth century, and the three chemical revolutionary periods, analytical chemistry has successfully evolved from the verge of the nineteenth century to modern and contemporary times, characterized by its versatile traits and unprecedented challenges in the twenty-first century. Historically, analytical chemistry can be termed as the mother of chemistry, as the nature and the composition of materials are always needed to be iden- tified first for specific utilizations subsequently; therefore, the development of analytical chemistry has always been ahead of general chemistry [2]. During pre-Hellenistic times when chemistry did not exist as a science, various ana- lytical processes, for example, qualitative touchstone method and quantitative fire-assay or cupellation scheme have been in existence as routine quality control measures for the purpose of noble goods authentication and anti-counterfeiting practices. Because of the unavailability of archeological clues for origin tracing, the chemical balance and the weights, as stated in the earliest documents ever found, was supposed to have been used only by the Gods [3]. -

North East Region Schools' Analyst 2011

ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY ANALYTICAL DIVISION NE Region SCHOOLS’ ANALYST COMPETITION 2011 Regional Heat The case of the Dying Marrows INSTRUCTION BOOKLET Instruction 2011 v4 Introduction In the sleepy village of Early Winter, little has changed for decades. Located twenty miles from the nearest town, the majority of the population have lived in the village all their lives and many are now retired. There is a small shop, post office, public house, school and church in the village centre. Surrounding the village are several small farms, each with a small herd of dairy cattle. Life in the village tends to focus on rural activities, with the annual village show being the highlight of the year. The prizes awarded for local produce are fiercely contested and behind the tranquil scenes emotions can run high, after all there is considerable pride at stake. Retired Colonel Smith has run the public house for the last twelve years. He is highly respected and popular in the village; his hobby is growing prize vegetable marrows. His marrows have won the village show for three years running, much to the annoyance of Mrs Dale (who runs the small shop); she also grows marrows, and has been second place at the show for the last three years. The one thing that really annoys Mrs Dale is that she sells the plant fertiliser to Colonel Smith, the very thing that makes his marrows the best. She has often told him that one day she will “replace the fertiliser with water before you buy it, then look what will happen to your marrows”. -

Conceptual Approach to Thermal Analysis and Its Main Applications

Prospect. Vol. 15, No. 2, Julio-Diciembre de 2017, 117-125 Conceptual approach to thermal analysis and its main applications Aproximación conceptual al análisis térmico y sus principales aplicaciones Alejandra María Zambrano Arévalo1*, Grey Cecilia Castellar Ortega2, William Andrés Vallejo Lozada3, Ismael Enrique Piñeres Ariza4, María Mercedes Cely Bautista5, Jesús Sigifredo Valencia Ríos6 1*M.Sc. Chemical Sciences, Full Professor, Universidad de la Costa. Barranquilla-Colombia. 2M.Sc. Chemical Sciences, Full Professor, Universidad Autónoma del Caribe. Barranquilla-Colombia. 3Ph.D. Chemical Sciences, Full Professor, Universidad del Atlántico. Barranquilla-Colombia. 4M.Sc. Physical Sciences, Occasional Full Professor, Universidad del Atlántico. Barranquilla-Colombia. 5Ph.D. Engineering, Full Professsor, Universidad Autónoma del Caribe. Barranquilla-Colombia. 6Ph. D. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Vicerrector Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Sede Palmira). Palmira-Colombia. E-mail: [email protected] Recibido 12/04/2017 Cite this article as: A. Zambrano, G.Castellar, W.Vallejo, I.Piñeres, M.M. Aceptado 28/05/2017 Cely, J.Valencia, Aproximación conceptual al análisis térmico y sus principales aplicaciones, “Conceptual approach to thermal analysis and its main applications”. Prospectiva, Vol 15, N° 2, 117-125, 2017. ABSTRACT This work shows to the reader a general description about the techniques of classic thermal analysis as known as Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Thermal Gravimetric Analysis. These techniques are very used in science and material technologies (metals, metals alloys, ceramics, glass, polymer, plastic and composites) with the purpose of characterizing precursors, following and control of process, adjustment of operation conditions, thermal treatment and verifying of quality parameters. Key words: Physical chemistry; Calorimetry; Thermochemistry; Thermal analysis. -

Physicochemical Characteristics of Protein Isolated from Thraustochytrid Oilcake

foods Article Physicochemical Characteristics of Protein Isolated from Thraustochytrid Oilcake Thi Linh Nham Tran 1,2, Ana F. Miranda 1 , Aidyn Mouradov 1,* and Benu Adhikari 1 1 School of Science, RMIT University, Bundoora Campus, Melbourne, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] (T.L.N.T.); [email protected] (A.F.M.); [email protected] (B.A.) 2 Faculty of Agriculture Bac Lieu University, 8 wards, Bac Lieu 960000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-99257144 Received: 13 May 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 11 June 2020 Abstract: The oil from thraustochytrids, unicellular heterotrophic marine protists, is increasingly used in the food and biotechnological industries as it is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, squalene and a broad spectrum of carotenoids. This study showed that the oilcake, a by-product of oil extraction, is equally valuable as it contained 38% protein/dry mass, and thraustochytrid protein isolate can be obtained with 92% protein content and recovered with 70% efficiency. The highest and lowest solubilities of proteins were observed at pH 12.0 and 4.0, respectively, the latter being its isoelectric point. Aspartic acid, glutamic acid, histidine, and arginine were the most abundant amino acids in proteins. The arginine-to-lysine ratio was higher than one, which is desired in heart-healthy foods. The denaturation temperature of proteins ranged from 167.8–174.5 ◦C, indicating its high thermal stability. Proteins also showed high emulsion activity (784.1 m2/g) and emulsion stability (209.9 min) indices. The extracted omega-3-rich oil melted in the range of 30–34.6 ◦C and remained stable up to 163–213 ◦C. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride -

Interagency Committee on Chemical Management

DECEMBER 14, 2018 INTERAGENCY COMMITTEE ON CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 13-17 REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR WALKE, PETER Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 II. Recommended Statutory Amendments or Regulatory Changes to Existing Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements that are Required to Facilitate Assessment of Risks to Human Health and the Environment Posed by Chemical Use in the State ............................................................................................................................ 5 III. Summary of Chemical Use in the State Based on Reported Chemical Inventories....... 8 IV. Summary of Identified Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Reported Chemical Inventories ........................................................................................................... 9 V. Summary of any change under Federal Statute or Rule affecting the Regulation of Chemicals in the State ....................................................................................................... 12 VI. Recommended Legislative or Regulatory Action to Reduce Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Regulated and Unregulated Chemicals of Emerging Concern .............................................................................................................................. -

High Performance Liquid Chromatography Method Development and Chemometric Analysis of Ecstasy and Cocaine

institlüld ictterkcnny TeicneoUiochti institute lyit (.«Ulf C*»n«lon of Technology High performance liquid chromatography method development and chemometric analysis of ecstasy and cocaine Kim McFadden Supervisors Dr. B. F. Carney, Letterkenny Institute of Technology Dr. D. O'Driscoll, Forensic Science Laboratory, Dublin Submitted to Higher bducation and Training Awards Council (HETAC) in fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HPLC method development & chemomelric analysis of ecstasy & cocaine Declaration I hereby declare that the work herein, submitted for Ph.D. in Analytical Science at Letterkenny Institute of Technology, is the result of my own investigation, except where reference is made to published literature. I also certify that the material submitted in this thesis has not been previously submitted for any other qualification. Kim McFadden 1 HPLC method development & chemometric analysis of ecstasy & cocaine Table of Contents Declaration 1 Abstract 5 List of Abbreviations 7 List of Figures 10 List of Tables 14 List of Presentations and Publications 16 Acknowledgments 18 Chapter 1: Literature review. 19 1.1. Introduction. 20 1.2. Drugs of abuse. 21 1.2.1. Narcotics. 22 1.2.2. Depressants. 24 1.2.3. Stimulants. 24 1.2.4. Hallucinogens. 25 1.2.5. Ecstasy. 26 1.2.6. Cocaine. 31 1.3. Current analytical techniques for forensic drug analysis. 34 1.3.1. Spectrometric methods. 34 1.3.2. Chromatographic methods. 36 1.4. Fundamentals of High Performance Liquid Chromatography. 40 1.4.1. Chromatographic interactions. 40 1.4.2. Mobile phase. 41 1.4.3. The column. 42 1.4.4.