Beryl Vertue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Martin Clune's Citation

9 Nov 2007, 1030 MARTIN CLUNES Pro-Chancellor, Martin Clunes is an actor of national renown who has played in a very wide range of film, television and stage productions, and first achieved his huge following for his role as Gary in Men Behaving Badly. His many other successes include the lead role in Doc Martin, and in feature films such as Shakespeare in Love. He is a son of the classical actor Alec Clunes and a cousin of the late Jeremy Brett, television’s Sherlock Holmes, so perhaps Martin’s school should not have been taken by surprise when he told the careers adviser that he too wanted to be an actor. The headmaster was discouraging (‘it’s not going to happen: buckle down’) but a teacher who evidently had some foresight saw his potential and put him in Love’s Labour’s Lost as Costard, the clown who is also very much at home with wit and wordplay. So his first performance was a comedy part in a classic play, and if comedy drama has been his forte ever since, he has by no means lost contact with the classics. Martin went to the Arts Educational Schools in London, on the strength of an audition, at the age of 16, and then into repertory, now more often playing Shakespeare’s courtiers than his fools. He made his name in the long-running TV situation comedy Men Behaving Badly, where he played Gary Strang, a character described (and I quote) as a ‘lager-loving loafer’. The show, its stars and and its writer have won many awards, and it was voted the best sitcom in the BBC's history at the Corporation's 60th anniversary celebrations in 1996. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

The Norman Conquest: the Style and Legacy of All in the Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2016 The Norman conquest: the style and legacy of All in the Family https://hdl.handle.net/2144/17119 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION Thesis THE NORMAN CONQUEST: THE STYLE AND LEGACY OF ALL IN THE FAMILY by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE B.A., Emerson College, 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 © 2016 by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE All rights reserved Approved by First Reader ___________________________________________________ Deborah L. Jaramillo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Film and Television Second Reader ___________________________________________________ Michael Loman Professor of Television DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Jean Lizotte, Nicholas Clark, and Alvin Delpino. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’m exceedingly thankful for the guidance and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Deborah Jaramillo, whose investment and dedication to this project allowed me to explore a topic close to my heart. I am also grateful for the guidance of my second reader, Michael Loman, whose professional experience and insight proved invaluable to my work. Additionally, I am indebted to all of the professors in the Film and Television Studies program who have facilitated my growth as a viewer and a scholar, especially Ray Carney, Charles Warren, Roy Grundmann, and John Bernstein. Thank you to David Kociemba, whose advice and encouragement has been greatly appreciated throughout this entire process. A special thank you to my fellow graduate students, especially Sarah Crane, Dani Franco, Jess Lajoie, Victoria Quamme, and Sophie Summergrad. -

Films and Comedy Quiz – 25Th June ¦ ANSWERS

Films and Comedy Quiz – 25th June ¦ ANSWERS 1. In which film does Alec Guinness's character plan and carry out a theft of gold bullion? (The film also starred Stanley Holloway, Sidney James and Audrey Hepburn.) The Lavender Hill Mob 2. A Night to Remember, of 1958, was about which disaster? The sinking of the Titanic 3. Which Ealing film of 1955 sees a gang of criminals defeated by their little old landlady? The Ladykillers 4. Which Hitchcock film has James Stewart's character confined to his room from which he spies on his neighbours? Rear Window 5. Which 'post-World War IIl' film starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Anthony Perkins, is based on a novel by Neville Shute? On the Beach 6. Which 1956 film, starring Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr was a remake of Anna and the King of Siam? The King and I 7. Which 1957 British film, starring Alastair Sim and Joyce Grenfell, sees a group of unruly schoolgirls going off on a UNESCO prize trip to Rome? Blue Murder at St Trinian's 8. Gregory Peck starred in which film of 1956 based on a Herman Melville novel? Moby Dick 9. Who wrote the music for West Side Story? Leonard Bernstein 10. Which was the first James Bond film? Doctor No 11. In which black comedy film did Peter Sellers play an RAF officer, a mad scientist and a US President? Dr Strangelove 12. Who were the two main stars in Midnight Cowboy? Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight 13. The Sentinel, a short story by Arthur C Clarke, was the basis for which film? 2001: A Space Odyssey 14. -

Telling the True Story

Bachelor Thesis Telling The True Story Queerbaiting, representation, and fan resistance in the BBC Sherlock fandom Suzanne Frenk 613191 Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen (Culture Studies) School of Humanities Tilburg University Supervisor: Dr. P. K. Varis Second Reader: Dr. I. E. L. Maly August 18, 2017 Synopsis In this thesis, I follow an online community on Tumblr revolving around a self- proclaimed conspiracy theory called TJLC. This group is part of the broader community of fans of the BBC TV show Sherlock, and is focused on ‘The Johnlock Conspiracy’: the belief that the two main characters of the show, John and Sherlock, are bisexual and gay, respectively, and will ultimately end up as a romantic couple, which would make Sherlock a mainstream TV show with explicit and positive LGBTQIA+ representation. This visibility is especially important to LGBTQIA+ individuals within the TJLC community, who want to see their identities more often and more accurately represented on television. The fact that the creators of Sherlock, as well as several of the actors in the show, are either part of the LGBTQIA+ community themselves or known supporters, works to further strengthen TJLC’ers’ trust in the inevitable unfolding of the story into a romantic plot. The fact that the TJLC community is based on a conspiracy theory not only makes it a remarkable example of fan culture, but has also led to many close readings of the show and its characters – from the textual level to symbolism to the musical score – on a level that can often be seen as close to academic. These pieces of so-called ‘meta’ have led to many predictions about the direction of the show, such as the strong belief that ‘Johnlock’ would become real in season four of the series. -

Frons Launches Soap Sensation

et al.: SU Variety II SPECIAL 'GOIN' HOLLYWOOD' EDITION II NEWSPAPER Second Class P.O. Entry Supplement to Syracuse University Magazine CURTIS: IN MINIS Role Credits! "War" Series Is All-Time Screen Dream Syracuse- We couldn't pos sibly get 'em all, but in these 8 By RENEE LEVY series "Winds of War," based on to air in late spring and the entire pages find another 40-plus SU Hollywood- The longest. The Herman Wouk 's epic World War II package will air in Europe next year. alumni getting billboards on most demanding. The hardest. The novels, "War and Remembrance" Curtis, exec producer, director the boulevard. In our research, most expensive. That's the story was shot in 757 locations in 10 and co-scribe of the teleplay, spent we discovered a staggering net behind Dan Curtis 'SO's block countries, using more than 44,000 two years filming and a year and a work of Syracusans in the busi buster miniseries " War and Re actors and extras and nearly 800 half editing "War and Remem ness-producers, directors, membrance," which aired the first sets. The production- the longest brance," a project he originally actors, editors, and more! We 18 of its 30 hours in November on in television history--cost an es considered undoable-particular soon realized that all of them ABC-TV. timated $ 105 million to make. The ly because of the naval battles and would not fit, and to those left A sequel to Curtis's 1983 maxi- concluding 12 hours are expected the depiction of the Holocaust. -

Annual Report 2014 Fueling the LGBT Movement Letter from the Board Chair & Executive Director

Annual Report 2014 Fueling the LGBT Movement Letter from the Board Chair & Executive Director This report is about 2014. Yet as this letter is written in 2015, it’s impossible not to start by recognizing the spectacular recent progress of the movement for the rights and dignity of LGBT people: the move to eliminate the ban on transgender people serving in the military; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruling that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is illegal; and, of course, the grand marriage victory at the Supreme Court. As we celebrate this dramatic progress, we all know that it comes out of the passion and sacrifices of countless people and the unflagging work of thousands of nonprofit groups, large and small. A relative few make headlines or become well known, but it is the many – not just the few – who make social change happen. These triumphs belong to all of us. Horizons Foundation has had the great privilege of not only being part of many of these historic events, but helping to shape and fuel them. The foundation has been there early. It’s been there often. It’s been there again and again and again. Our first grant for work on LGBT marriage equality, for example, goes back nearly two decades. Our first grant in support of transgender rights happened nearly as long ago. Horizons made the first grant anywhere to fight HIV. As this report relates, the year 2014 – the foundation’s 34th year – built on this powerful legacy. We are especially glad to share the remarkable list of grants made to organizations in every part of the LGBT community, as well as indicators of strong financial growth. -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

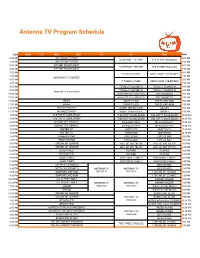

Antenna TV Program Schedule

Antenna TV Program Schedule East MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN West 5:00 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 5:30 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:30 AM 6:00 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 6:30 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:30 AM 7:00 AM 4:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 7:30 AM 4:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 8:00 AM 5:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 8:30 AM 5:30 AM 9:00 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:00 AM 9:30 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 10:00 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:00 AM 10:30 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:30 AM 11:00 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:00 AM 11:30 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:30 AM 12:00 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:00 AM 12:30 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:30 AM 1:00 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:00 AM 1:30 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:30 AM 2:00 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:00 AM 2:30 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:30 AM 3:00 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:00 PM 3:30 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:30 PM 4:00 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:00 PM 4:30 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:30 PM 5:00 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE ADV. -

Marriage Fifth Paper for Montana Church Workers' Conference 10

Marriage Fifth Paper for Montana Church Workers’ Conference 10/2020 Deac. Mary J Moerbe God’s Word echoes throughout creation. (I love that image from Luther). And what happens? All over the world, throughout every age, most people look to get married. People look for a helpmate. They make a lifelong commitment to care for this one person of the opposite sex until death. This is not dependent on a church wedding or Christianity. Scripture never questions foreign or unbeliever marriages, but teaches that marriage is an institution given to humanity during the time of creation’s perfection. Interestingly, Adam had no choice in his partner, nor did Eve. In the beginning, God made one flesh and from it came the second. Then the two came together again in a way “to be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion” (*Gen 1:28). God created them, brought them together, married them, and blessed them. He kept them in all the beautiful nuance of the ancient term. He made His face to shine upon them and was gracious to them. He lifted up His countenance upon them and gave them peace (Numbers 6:24-27). I don’t think it goes too far to say God keeps marriage. Marriage is the only relationship restricted to one other person, and, on this earth, it is decidedly marked with a beginning and an end. A man leaves his family to become one flesh with a woman. The two are united, bringing both sexes into a permanent relationship with lots of practical implications. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace.