The Wittgenstein Lectures-2019 Update Cambria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Suchoff Family Resemblances: Ludwig Wittgenstein As a Jewish Philosopher the Admonition to Silence with Which Wittgenstein

David Suchoff Family Resemblances: Ludwig Wittgenstein as a Jewish Philosopher The admonition to silence with which Wittgenstein ended the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) also marks the starting point for the emer- gence of his Jewish philosophical voice. Karl Kraus provides an instructive contrast: as a writer well known to Wittgenstein, Kraus’s outspoken and aggressive ridicule of “jüdeln” or “mauscheln” –the actual or alleged pronunciation of German with a Jewish or Yiddish accent – defined a “self-fashioning” of Jewish identity – from German and Hebrew in this case – that modeled false alternatives in philosophic terms.1 Kraus pre- sented Wittgenstein with an either-or choice between German and Jewish identity, while engaging in a witty but also unwitting illumination of the interplay between apparently exclusive alternatives that were linguistically influenced by the other’s voice. As Kraus became a touchstone for Ger- man Jewish writers from Franz Kafka to Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, he also shed light on the situation that allowed Wittgenstein to develop his own non-essentialist notion of identity, as the term “family resemblance” emerged from his revaluation of the discourse around Judaism. This transition from The False Prison, as David Pears calls Wittgenstein’s move from the Tractatus to the Philosophical Investiga- tions, was also a transformation of the opposition between German and Jewish “identities,” and a recovery of the multiple differences from which such apparently stable entities continually draw in their interconnected forms of life.2 “I’ll teach you differences,” the line from King Lear that Wittgenstein mentioned to M. O’C. Drury as “not bad” as a “motto” for the Philo- sophical Investigations, in this way represents Wittgenstein’s assertion of a German Jewish philosophic position. -

Unit 13 Emotivism: Charles Stevenson*

Emotivism: Charles UNIT 13 EMOTIVISM: CHARLES Stevenson STEVENSON* Structure 13.0 Objectives 13.1 Introduction 13.2 Definition 13.3 The Significance of Emotivism in Moral Philosophy 13.4 Philosophical Views 13.5 Let Us Sum Up 13.6 Key Words 13.7 Further Readings and References 13.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 13.0 OBJECTIVES This unit provides: An introductory understanding and significance of emotivism in moral and ethical philosophy. Many aspects of emotivism have been explored by philosophers in the history of modern philosophy but this unit focuses Charles Stevenson’s version of emotivism. 13.1 INTRODUCTION Emotivism is a meta-ethical theory in moral philosophy, which was developed by the American philosopher Charles Stevenson (1908-1978). He was born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1908. He studied philosophy under G E Moore and Ludwig Wittgenstein, and was most influenced by the latter. From 1933 onwards, and continuing after the war, he developed the emotive theory of ethics at the University of Harvard. Stevenson’s contributions were largely in the area of meta-ethics. Post-war debates in the field of ethics were charceterised by ‘the linguistic turn’ in philosophy, and the increasing emphasis of scientific knowledge on philosophy, especially under the influence of the school of Logical Positivism. Questions such as, do ‘scientific facts’ play a role in ethical considerations? how far feelings and emotions influence our understanding of morality?, became significant. Therefore, to respond to these and related issues, philosophers developed different ethical theories. Stevenson was one of the philosophers who developed the theory of emotivism against this backdrop, and defended his theory to justify how feelings and non-cognitive attributes constitute our understanding of morality and moral judgments. -

'Solved by Sacrifice' : Austin Farrer, Fideism, and The

‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’ : AUSTIN FARRER, FIDEISM, AND THE EVIDENCE OF FAITH Robert Carroll MacSwain A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in the St Andrews Digital Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/920 This item is protected by original copyright ‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’: Austin Farrer, Fideism, and the Evidence of Faith Robert Carroll MacSwain A thesis submitted to the School of Divinity of the University of St Andrews in candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The saints confute the logicians, but they do not confute them by logic but by sanctity. They do not prove the real connection between the religious symbols and the everyday realities by logical demonstration, but by life. Solvitur ambulando, said someone about Zeno’s paradox, which proves the impossibility of physical motion. It is solved by walking. Solvitur immolando, says the saint, about the paradox of the logicians. It is solved by sacrifice. —Austin Farrer v ABSTRACT 1. A perennial (if controversial) concern in both theology and philosophy of religion is whether religious belief is ‘reasonable’. Austin Farrer (1904-1968) is widely thought to affirm a positive answer to this concern. Chapter One surveys three interpretations of Farrer on ‘the believer’s reasons’ and thus sets the stage for our investigation into the development of his religious epistemology. 2. The disputed question of whether Farrer became ‘a sort of fideist’ is complicated by the many definitions of fideism. -

Linguistic Scepticism in Mauthner's Philosophy

LiberaPisano Misunderstanding Metaphors: Linguistic ScepticisminMauthner’s Philosophy Nous sommes tous dans un désert. Personne ne comprend personne. Gustave Flaubert¹ This essayisanoverview of Fritz Mauthner’slinguistic scepticism, which, in my view, represents apowerful hermeneutic category of philosophical doubts about the com- municative,epistemological, and ontological value of language. In order to shed light on the main features of Mauthner’sthought, Idrawattention to his long-stand- ing dialogue with both the sceptical tradition and philosophyoflanguage. This con- tribution has nine short sections: the first has an introductory function and illus- tratesseveral aspectsoflinguistic scepticism in the history of philosophy; the second offers acontextualisation of Mauthner’sphilosophyoflanguage; the remain- der present abroad examination of the main features of Mauthner’sthought as fol- lows: the impossibility of knowledge that stems from aradicalisationofempiricism; the coincidencebetween wordand thought,thinkingand speaking;the notion of use, the relevanceoflinguistic habits,and the utopia of communication; the decep- tive metaphors at the root of an epoché of meaning;the new task of philosophyasan exercise of liberation against the limits of language; the controversial relationship between Judaism and scepticism; and the mystical silence as an extreme conse- quence of his thought.² Mauthnerturns scepticism into aform of life and philosophy into acritique of language, and he inauguratesanew approach that is traceable in manyGerman—Jewish -

Kreisel and Wittgenstein

Kreisel and Wittgenstein Akihiro Kanamori September 17, 2018 Georg Kreisel (15 September 1923 { 1 March 2015) was a formidable math- ematical logician during a formative period when the subject was becoming a sophisticated field at the crossing of mathematics and logic. Both with his technical sophistication for his time and his dialectical engagement with man- dates, aspirations and goals, he inspired wide-ranging investigation in the meta- mathematics of constructivity, proof theory and generalized recursion theory. Kreisel's mathematics and interactions with colleagues and students have been memorably described in Kreiseliana ([Odifreddi, 1996]). At a different level of interpersonal conceptual interaction, Kreisel during his life time had extended engagement with two celebrated logicians, the mathematical Kurt G¨odeland the philosophical Ludwig Wittgenstein. About G¨odel,with modern mathemat- ical logic palpably emanating from his work, Kreisel has reflected and written over a wide mathematical landscape. About Wittgenstein on the other hand, with an early personal connection established Kreisel would return as if with an anxiety of influence to their ways of thinking about logic and mathematics, ever in a sort of dialectic interplay. In what follows we draw this out through his published essays|and one letter|both to elicit aspects of influence in his own terms and to set out a picture of Kreisel's evolving thinking about logic and mathematics in comparative relief.1 As a conceit, we divide Kreisel's engagements with Wittgenstein into the \early", \middle", and \later" Kreisel, and account for each in successive sec- tions. x1 has the \early" Kreisel directly interacting with Wittgenstein in the 1940s and initial work on constructive content of proofs. -

THE UNIVERSITY of WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT of PHILOSOPHY Graduate Course Outline 2016-17

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY Graduate Course Outline 2016-17 Philosophy 9653A: Proseminar Fall Term 2016 Instructor: Robert J. Stainton Class Days and Hours: W 2:30-5:30 Office: StH 3126 Office Hours: Tu 2:00-3:00 Classroom: TBA Phone: 519-661-2111 ext. 82757 Web Site: Email: [email protected] http://publish.uwo.ca/~rstainto/ Blog: https://robstainton.wordpress.com/ DESCRIPTION A survey of foundational and highly influential texts in Analytic Philosophy. Emphasis will be on four sub-topics, namely Language and Philosophical Logic, Methodology, Ethics and Epistemology. Thematically, the focal point across all sub-topics will be the tools and techniques highlighted in these texts, which reappear across Analytic philosophy. REQUIRED TEXT A.P. Martinich and David Sosa (eds.)(2011) Analytic Philosophy: An Anthology. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [All papers except the Stine and Thomson are reprinted here.] OBJECTIVES The twin objectives are honing of philosophical skills and enriching students’ familiarity with some “touchstone” material in 20th Century Analytic philosophy. In terms of skills, the emphasis will be on: professional-level philosophical writing; close reading of notoriously challenging texts; metaphilosophical reflection; and respectful philosophical dialogue. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Twelve weekly “Briefing Notes” on Selected Readings: 60% Three “Revised Brief Notes”: 25% Class Participation: 15% COURSE READINGS Language and Philosophical Logic Gottlob Frege (1892), “On Sense and Reference” Gottlob Frege (1918), “The Thought” Bertrand Russell (1905), “On Denoting” Ludwig Wittgenstein (1933-35 [1958]), Excerpts from The Blue and Brown Books Peter F. Strawson (1950), “On Referring” H. Paul Grice (1957), “Meaning” H. Paul Grice (1975), “Logic and Conversation” Saul Kripke (1971), “Identity and Necessity” Hilary Putnam (1973), “Meaning and Reference” Methodology A.J. -

Realismus – Relativismus – Konstruktivismus Realism – Relativism – Constructivism

Realismus – Relativismus – Konstruktivismus Realism – Relativism – Constructivism Programm des 38. Internationalen Wittgenstein Symposiums 9. – 15. August 2015 Kirchberg am Wechsel Program of the 38th International Wittgenstein Symposium August 9 – 15, 2015 Kirchberg am Wechsel Für aktuelle Programmänderungen beachten Sie bitte die Aushänge oder siehe: http://www.alws.at/program_2015.pdf. www.alws.at Program subject to change, for updates please refer to the postings or go to: http://www.alws.at/program_2015.pdf. Wir danken folgenden Institutionen und Personen für die finanzielle Unterstützung des Symposiums: We thank the following institutions and persons for their financial support of the symposium: Landeshauptmann von Niederösterreich Dr. Erwin Pröll Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, Abteilung Wissenschaft und Forschung Hofrat Dr. Joachim Rössl Mag. Paul Pennerstorfer Mag. Georg Pejrimovsky Mag. Matthias Kafka Marktgemeinde Kirchberg am Wechsel Bürgermeister DI Dr. Willibald Fuchs Gemeinde Trattenbach Bürgermeister Johannes Hennerfeind Raiffeisenbank NÖ-Alpin Direktor Johannes Pepelnik Leader Region Bucklige Welt-Wechselland Leader-Manager Franz Piribauer Kurdirektorin Maria Haarhofer Sound Art Service, Stefan Schlögl Gasthof Grüner Baum, Kirchberg am Wechsel Gasthof St. Wolfgang, Kirchberg am Wechsel Gasthof zur 1000-jährigen Linde, Kirchberg am Wechsel Familie Hennrich Taxi – Autobusunternehmen Karl Mayerhofer Kleinbusunternehmen Ingrid Fahrner Impressum: Eigentümer, Verleger und Herausgeber: Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft, Markt 63, A-2880 Kirchberg am Wechsel. Redaktion des Programms: Christian Kanzian, Josef Mitterer, Katharina Neges. Visuelle Gestaltung: Sascha Windholz. Druck: Eigner Druck; 3040 Neulengbach. Beiträge, Abstrakta-Heft und Programm wurden mit Hilfe eines von Joseph Wang, Universität Innsbruck, erarbeiteten Datenbankprogramms erstellt. Kontakt: [email protected] Papers, book of abstracts and program were produced using a database application developed by Joseph Wang, University of Innsbruck, Austria. -

Artificial Intelligence and Language Old Questions in a New Key

COMPLEX AI-BASED SYSTEMS AND THE FUTURES OF LANGUAGE, HENRIK SINDING-LARSEN (ed) KNOWLEDGE AND RESPONSIBILITY IN PROFESSIONS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND LANGUAGE OLD QUESTIONS IN A NEW KEY 7/88 CompLex nr. 7/88 AI based systems and the future of language, knowledge and responsibility in professions A COST-13 project Secretariat: Swedish Center for Working Life Box 5606 S-l 1486 STOCKHOLM - Sweden Henrik Sinding-Larsen (ed.) ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND LANGUAGE Old questions in a new key TANO OSLO © Tano A.S. 1988 ISBN 82-518-2550-4 Printed in Norway by Engers Boktrykkeri A/S, Otta Preface This report is based on papers, presentations and ideas from the research seminar Artificial Intelligence and Language that took place at Hotel Lutetia, Paris 2.-4. November 1987. The seminar was organised by the research project AI-based Systems and the Future of Language, Knowledge and Responsibility in Professions. The seminar as well as the project was financed by a grant from the Commission of the European Communities through the research programme COST-13. The project has been initiated and conducted by the following institutions: • Institute of informatics, University of Oslo • Swedish Centre for Working Life, Stockholm • Norwegian Research Institute for Computers and Law, University of Oslo • Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Vienna The project secretariat has been at the Swedish Centre for Working Life, Box 5606, S - 11486 Stockholm, Sweden. Project coordinator has been professor Kristen Nygaard, Institute of informatics, University of Oslo. An important activity within the project has been to create a forum for collaboration among European researchers from different disciplines concerned with the impact of artificial intelligence on society and culture. -

A Defence of Emotivism

A Defence of Emotivism Leslie Allan Published online: 16 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 Leslie Allan As a non-cognitivist analysis of moral language, Charles Stevenson’s sophisticated emotivism is widely regarded by moral philosophers as a substantial improvement over its historical antecedent, radical emotivism. None the less, it has come in for its share of criticism. In this essay, Leslie Allan responds to the key philosophical objections to Stevenson’s thesis, arguing that the criticisms levelled against his meta-ethical theory rest largely on a too hasty reading of his works. To cite this essay: Allan, Leslie 2015. A Defence of Emotivism, URL = <http://www.RationalRealm.com/philosophy/ethics/defence-emotivism.html> To link to this essay: www.RationalRealm.com/philosophy/ethics/defence-emotivism.html Follow this and additional essays at: www.RationalRealm.com This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms and conditions of access and use can be found at www.RationalRealm.com/policies/tos.html Leslie Allan A Defence of Emotivism 1. Introduction In this essay, my aim is to defend an emotive theory of ethics. The particular version that I will support is based on C. L. Stevenson’s signal work in Ethics and Language [1976], originally published in 1944, and his later revisions and refinements to this theory presented in his book, Facts and Values [1963]. I shall not, therefore, concern myself with the earlier and less sophisticated versions of the emotive theory, such as those presented by A. -

Philosophy at Cambridge Newsletter of the Faculty of Philosophy Issue 14 May 2017

Philosophy at Cambridge Newsletter of the Faculty of Philosophy Issue 14 May 2017 ISSN 2046-9632 From the Chair Tim Crane Many readers will know that the British Government’s periodic assessment of research quality in universities now involves an assessment of the ‘impact’ of this research on the world. In the 2014 exercise, demonstrations of impact were supposed to trace a causal chain from the original research to some effect in the ‘outside world’. It’s hard to know how the ‘impact’ approach would have handled with the achievements of Bernard Williams, one of the Cambridge philosophers we have celebrated this year – in his case with a conference in the Autumn of 2016 on Williams and the Ancients at Newnham College, organised by Nakul Krishna and Sophia Connell (pp. 2 & 3). In numerous ways, Williams had an impact in the public sphere, and his work has profound Onora O’Neill has been named the winner of the 2017 Holberg Prize. Photo: Martin Dijkstra implications for our understanding of politics. But it’s hard to see how one could this way is Casimir Lewy, whose life and Central European University in August. trace any of these effects back through work we celebrated at a delightful event at It’s been an exciting period in the Faculty, a simple chain to one or two ideas. Trinity College in February (p. 6). The list of with many new appointments and Another example of a Cambridge philosophers Lewy taught in his 30 years in unprecedented success in acquiring philosopher who is still a leading public Cambridge contains some of the leading research grants. -

A “Family Tree” of Ethical Theories

A “Family Tree” of Ethical Theories [This is section 10.10 of the draft of my book The Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Class Interest Theory of Ethics. –JSH] Chart 10.1 in this section is an effort to depict the relationships between the various types of ethical theories, and specifically how other ethical theories relate to the MLM class interest theory of ethics. The idea is to look for the most fundamental division among the various types of theories and to separate them into two groups on that basis. Then to further divide the remaining theories in each group in the same way, leading to sort of a “family tree” of ethical theories based—not on how they actually evolved—but rather on how they relate to each other logically. The chart has a lot of information in it and may be somewhat hard to initially comprehend. For that reason I am further explaining it below. In the chart I have also printed in red the attributes or categories which encompass the two moral systems supported by MLM ethical theory (i.e., proletarian morality and communist morality). The first big division among ethical theories is between COGNITIVISM and NON- COGNITIVISM. Cognitivism holds that moral judgments are meaningful, and that they are true or false. Somewhat amazingly, there are numerous theories of ethics which deny this, and hence deny that it is meaningful and/or true to say, for example, that genocide is wrong! The logical positivists, in particular, claimed that moral judgments are meaningless. Some people in this general positivist tradition, including Charles Stevenson, went on to claim that moral judgments are merely expressions of emotion and “commands” that others have the same emotional reaction to something as the speaker does. -

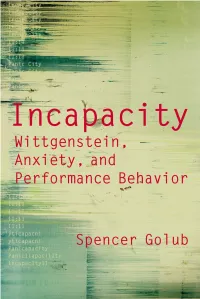

Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior

Incapacity Incapacity Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior Spencer Golub northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2014 by Spencer Golub. Published 2014 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Golub, Spencer, author. Incapacity : Wittgenstein, anxiety, and performance behavior / Spencer Golub. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8101-2992-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Wittgenstein, Ludwig, 1889–1951. 2. Language and languages—Philosophy. 3. Performance—Philosophy. 4. Literature, Modern—20th century—History and criticism. 5. Literature—Philosophy. I. Title. B3376.W564G655 2014 121.68—dc23 2014011601 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Golub, Spencer. Incapacity: Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2014. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. For my mother We go towards the thing we mean. —Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, §455 .