JOHNSON-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (1.497Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Reid, Alex Communications EDRS PRICE on Technology. Now

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 062 803 EM 009 846 AUTHOR Reid, Alex TITLE New Directio:Is inTelecommunications Research. INSTITUTION Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, New York,N.Y. PUB DATE Jun 71 NOTE 62p.; Report of the SloanCommission cn Cable Communications EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTCRS Cable Television; City Planning;Communications; Human Engineering; InformationSystems; Information Theory; Man Machine Systems; *MediaResearch; *Research Needs; *Telecommunication;Telephone Communications Industry IDENTIFIERS *Sloan Commission on CableCommunications ABSTRACT Telecommunications research has been focusedmainly on technology. Nowresearch about the human factorsis crucial. This can be divided intofour areas.(1) TLe needs telecommunicationsmust satisfy--needs can be extrapolated from currentbehavior.(2) The technological alternatives available--importantdevelopments are being made in transmission andswitching equipment and user terminals. (3) The effectiveness of thealternatives for meeting the needs--studies should combine the laboratoryand outside world and should focus on typical consumers aswell as business users.(4) The secondary effects--impact studies aredifficult and usually begin after the impact has been felt. Animpact study approach can be to ask what constraints would beloosened by the presence of a technological development. For example, lower costtelecommunications would remove one constraint on longdistance calls and could lead to new group associations.Several disciplines are relevant toresearch that is needed, including informationtheory, management studies, psychology, sociology, urban and regionalplanning and geogTaphy. (MG) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Framing a Narrative of Discrimination Under the Eighth Amendment in the Context of Transgender Prisoner Health Care Sarah Halbach

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 105 | Issue 2 Article 5 Spring 2015 Framing a Narrative of Discrimination Under the Eighth Amendment in the Context of Transgender Prisoner Health Care Sarah Halbach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Sarah Halbach, Framing a Narrative of Discrimination Under the Eighth Amendment in the Context of Transgender Prisoner Health Care, 105 J. Crim. L. & Criminology (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol105/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 5. HALBACH (FINAL TO PRINTER) 7/20/2016 0091-4169/15/10502-0463 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 105, No. 2 Copyright © 2016 by Sarah Halbach Printed in U.S.A. FRAMING A NARRATIVE OF DISCRIMINATION UNDER THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF TRANSGENDER PRISONER HEALTH CARE Sarah Halbach* This Comment looks closely at the reasoning behind two recent federal court opinions granting transgender prisoners access to hormone therapy and sex-reassignment surgery. Although both opinions were decided under the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, which does not expressly prohibit discrimination based on gender identity, a careful look at the courts’ reasoning suggests that they were influenced by the apparent discrimination against the transgender plaintiffs. This Comment argues that future transgender prisoners may be able to develop an antidiscrimination doctrine within the Eighth Amendment by framing their Eighth Amendment medical claims in terms of discrimination based on their transgender status. -

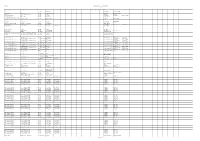

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

INCORPORATING TRANSGENDER VOICES INTO the DEVELOPMENT of PRISON POLICIES Kayleigh Smith

15 Hous. J. Health L. & Policy 253 Copyright © 2015 Kayleigh Smith Houston Journal of Health Law & Policy FREE TO BE ME: INCORPORATING TRANSGENDER VOICES INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRISON POLICIES Kayleigh Smith I. INTRODUCTION In the summer of 2013, Netflix aired its groundbreaking series about a women’s federal penitentiary, Orange is the New Black. One of the series’ most beloved characters is Sophia, a transgender woman who committed credit card fraud in order to pay for her sex reassignment surgeries.1 In one of the most poignant scenes of the entire first season, Sophia is in the clinic trying to regain access to the hormones she needs to maintain her physical transformation, and she tells the doctor with tears in her eyes, “I need my dosage. I have given five years, eighty thousand dollars, and my freedom for this. I am finally who I am supposed to be. I can’t go back.”2 Sophia is a fictional character, but her story is similar to the thousands of transgender individuals living within the United States prison system.3 In addition to a severe lack of physical and mental healthcare, many transgender individuals are harassed and assaulted, creating an environment that leads to suicide and self- 1 Orange is the New Black: Lesbian Request Denied (Netflix streamed July 11, 2013). Transgender actress Laverne Cox plays Sophia on Orange is the New Black. Cox’s rise to fame has given her a platform to speak about transgender rights in the mainstream media. See Saeed Jones, Laverne Cox is the Woman We Have Been Waiting For, BUZZFEED (Mar. -

There Better Be a Naked Cheerleader Under Your Bed‖

―THERE BETTER BE A NAKED CHEERLEADER UNDER YOUR BED‖: REPRESENTATIONS OF SOUTHERN, WORKING CLASS MASCULINITY IN KING OF THE HILL Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University–San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of ARTS by Joshua C. Shepherd, B.J. San Marcos, Texas May 2011 ―THERE BETTER BE A NAKED CHEERLEADER UNDER YOUR BED‖: REPRESENTATIONS OF SOUTHERN, WORKING CLASS MASCULINITY IN KING OF THE HILL Committee Members Approved: __________________________ Susan Weill, Chair __________________________ Kate Peirce __________________________ Cindy Royal Approved: __________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT By Joshua Charles Shepherd 2011 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author‘s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Joshua Shepherd, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the support and assistance from some wonderful people in my life. My supervisor, Dr. Susan Weill, professor at Texas State University-San Marcos, who guided me throughout this process and pushed me to become a better writer; Dr. Kate Peirce, professor at Texas State University-San Marcos for all her help and spawning this idea with her course on Gender and Media; Dr. -

Mojave Desert Land Trust 2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT MOJAVE DESERT LAND TRUST ABOUT MDLT MISSION: The Mojave Desert Land Trust protects the Mojave Desert ecosystem and its natural, scenic, and cultural resource values. VISION: Dark night skies, clean air and water, broad views and vistas, and an abundance of native plants and animals. Photo: Lucas Basulto/MDLT The Mojave Desert Land Trust (MDLT) protects the unique living landscapes of the California deserts. Our service area spans nearly 26 million acres - the entire California portion of the Mojave and Colorado deserts - about 25% of the state. Since 2006 we have secured permanent and lasting protection for over 90,000 acres across the California deserts. We envisage the California desert as a vital ecosystem of interconnected, permanently protected scenic and natural areas that host a diversity of native plants and wildlife. Views and vistas are broad. The air is clear, the water clean, and the night skies dark. Cities and military facilities are compact and separated by large natural areas. Residents, visitors, land managers, and political leaders value the unique environment in which they live and work, as well as the impacts of global climate change upon the desert ecosystem. MDLT shares our mission of protecting wildlife corridors, land conservation education, habitat management and restoration, research, and outreach with the general public so they too can become well informed and passionate protectors and stewards of our desert resources. Only through acquisition, stewardship, public awareness, and advocacy can -

Selected Filmography of Digital Culture and New Media Art

Dejan Grba SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY OF DIGITAL CULTURE AND NEW MEDIA ART This filmography comprises feature films, documentaries, TV shows, series and reports about digital culture and new media art. The selected feature films reflect the informatization of society, economy and politics in various ways, primarily on the conceptual and narrative plan. Feature films that directly thematize the digital paradigm can be found in the Film Lists section. Each entry is referenced with basic filmographic data: director’s name, title and production year, and production details are available online at IMDB, FilmWeb, FindAnyFilm, Metacritic etc. The coloured titles are links. Feature films Fritz Lang, Metropolis, 1926. Fritz Lang, M, 1931. William Cameron Menzies, Things to Come, 1936. Fritz Lang, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, 1960. Sidney Lumet, Fail-Safe, 1964. James B. Harris, The Bedford Incident, 1965. Jean-Luc Godard, Alphaville, 1965. Joseph Sargent, Colossus: The Forbin Project, 1970. Henri Verneuil, Le serpent, 1973. Alan J. Pakula, The Parallax View, 1974. Francis Ford Coppola, The Conversation, 1974. Sidney Pollack, The Three Days of Condor, 1975. George P. Cosmatos, The Cassandra Crossing, 1976. Sidney Lumet, Network, 1976. Robert Aldrich, Twilight's Last Gleaming, 1977. Michael Crichton, Coma, 1978. Brian De Palma, Blow Out, 1981. Steven Lisberger, Tron, 1982. Godfrey Reggio, Koyaanisqatsi, 1983. John Badham, WarGames, 1983. Roger Donaldson, No Way Out, 1987. F. Gary Gray, The Negotiator, 1988. John McTiernan, Die Hard, 1988. Phil Alden Robinson, Sneakers, 1992. Andrew Davis, The Fugitive, 1993. David Fincher, The Game, 1997. David Cronenberg, eXistenZ, 1999. Frank Oz, The Score, 2001. Tony Scott, Spy Game, 2001. -

The Submarine Review December 2017 Paid Dulles, Va Dulles, Us Postage Permit No

NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE DECEMBER 2017 5025D Backlick Road NON-PROFIT ORG. FEATURES Annandale, VA 22003 US POSTAGE PAID Repair and Rebuild - Extracts; American PERMIT NO. 3 Enterprise Institute DULLES, VA Ms. Mackenzie Eaglen..........................9 2017 Naval Submarine League History Seminar Transcript.................................24 Inside Hunt for Red October THE SUBMARINE REVIEW DECEMBER 2017 THE SUBMARINE REVIEW CAPT Jim Patton, USN, Ret..................67 Awardees Recognized at NSL Annual Symposium...........................................73 ESSAYS Battle of the Atlantic: Command of the Seas in a War of Attrition LCDR Ryan Hilger, USN...............85 Emerging Threats to Future Sea Based Strategic Deterrence CDR Timothy McGeehan, USN, .....97 Innovation in C3 for Undersea Assets LT James Davis, USN...................109 SUBMARINE COMMUNITY Canada’s Use of Submarines on Fisheries Patrols: Part 2 Mr. Michael Whitby.......................118 Career Decisions - Submarines RADM Dave Oliver, USN, Ret......125 States Put to Sea Mr. Richard Brown.........................131 Interview with a Hellenic Navy Subma- rine CO CAPT Ed Lundquist, USN, Ret.....144 The USS Dallas: Where Science and Technology Count Mr. Lester Paldy............................149 COVER_AGS.indd 1 12/11/17 9:59 AM THE SUBMARINE REVIEW DECEMBER 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Letter................................................................................................2 Editor’s Notes.....................................................................................................3