04 Monica Hahn 4교OK.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

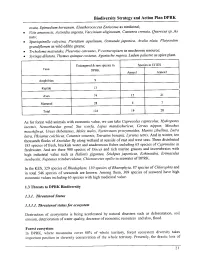

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Korea's Economy

2014 Overview and Macroeconomic Issues Lessons from the Economic Development Experience of South Korea Danny Leipziger The Role of Aid in Korea's Development Lee Kye Woo Future Prospects for the Korean Economy Jung Kyu-Chul Building a Creative Economy The Creative Economy of the Park Geun-hye Administration Cha Doo-won The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses KOREA Robert D. Atkinson Spurring the Development of Venture Capital in Korea Randall Jones ’S ECONOMY VOLUME 30 Economic Relations with Europe KOREA’S ECONOMY Korea’s Economic Relations with the EU and the Korea-EU FTA apublicationoftheKoreaEconomicInstituteof America Kang Yoo-duk VOLUME 30 and theKoreaInstituteforInternationalEconomicPolicy 130 years between Korea and Italy: Evaluation and Prospect Oh Tae Hyun 2014: 130 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Korea and Italy Angelo Gioe 130th Anniversary of Korea’s Economic Relations with Russia Jeong Yeo-cheon North Korea The Costs of Korean Unification: Realistic Lessons from the German Case Rudiger Frank President Park Geun-hye’s Unification Vision and Policy Jo Dongho Kor ea Economic Institute of America Korea Economic Institute of America 1800 K Street, NW Suite 1010 Washington, DC 20006 KEI EDITORIAL BOARD KEI Editor: Troy Stangarone Contract Editor: Gimga Group The Korea Economic Institute of America is registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the Government of the Republic of Korea. This material is filed with the Department of Justice, where the required registration statement is available for public inspection. Registration does not indicate U.S. -

North Korea Today” Describing the Way the North Korean People Live As Accurately As Possible

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY http://www.goodfriends.or.kr / [email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.296 September 2009 [“Good Friends” aims to help the North Korean people from a humanistic point of view and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as accurately as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ [Hot Topics] A Former Leader’s Exemplary Leadership Results in Joo-won Coalmine’s Record Output Construction Laborers Fight With Supervisors Ending in Mass Strike at Eorangchun Security Agents, “Blind with Money”, Cause Death to an Elderly Woman with Threats and Severe Beating Money Earned in “Bone-Shattering Struggles” Gone in a Morning [Food] Concerns Over Food Shortages for the Special Labor Brigade at Hoecheon Power Plant in Jagang Province Food Distribution Long Discontinued in Eunduk County, North Hamgyong Province [Economy] Food Crisis Will Double in Severity by 2010 Severity of Punishment for Harvest Related Infringements Heightened Due to the Food Crisis Food Crisis in 2010 to be Exacerbated by Drought this Year Street Vendors Complain about Increased Control over Business [Politics] August Policies of the Central Party 1 Regional High-Ranking Officers Being Investigated on Charges of Drug Trafficking [Society] Hambak Houses (Cheap boardinghouses) Flourishing in Boojon County South Hamgyong Province Farmers in Boojon County Produce Potatoes -

Two Nation States in the Korean Peninsula

Handbook of Asian States – Korea Dr Sojin Lim, University of Central Lancashire Two Nation States in the Korean Peninsula Natural space and geographical conditions The Korean Peninsula is located in the East Asia region, surrounded by China, Russia and Japan. Korea is the smallest country in the region. The total area of the Peninsula is about 220,880 km2, putting it at less than half the size of Japan, and slightly smaller than the United Kingdom (UK). The Peninsula is about 1,070 km long and about 300 km wide (Kwon et al., 2016). Across the middle of the Peninsula lies the 250 km long and 4 km wide Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) between North and South Koreas at the 38th parallel of latitude. The area of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, hereinafter, North Korea) is 12,054 km2, while the Republic of Korea (ROK, hereinafter, South Korea) covers 10,034 km2 (Statistics Korea, 2019a). The area of South Korea in the 1960s was 98,430 km2, but due to land reclamation efforts it has grown to the size it is today (Kwon et al., 2016). The DMZ is about 145 km south of Pyongyang, the capital city of North Korea, and about 50 km north of Seoul, the capital city of South Korea. The distance between Pyongyang and Seoul is about 195 km. The DMZ itself is 250 km long and about 4 km wide. The eastern part of the Peninsula has long, high mountain ranges, hills and streams, while the south-west region has a wide range of farmland with coastal plains. -

The Bacteriological War of 1952 Is a False Alarm'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September, 1997 Wu Zhili, 'The Bacteriological War of 1952 is a False Alarm' Citation: “Wu Zhili, 'The Bacteriological War of 1952 is a False Alarm',” September, 1997, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Yanhuang chunqiu no. 11 (2013): 36-39. Translated by Drew Casey. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/123080 Summary: Wu Zhili's claims that bacteriological warfare allegedly conducted by the United States in Korea in 1952 was a "false alarm." Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Chinese Transcription ([Yanhuang chunqiu] Editor’s Comment: This essay is the posthumous work of Comrade Wu Zhili, former director of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army Health Division. With the exception of a few sentences and obvious typographical errors, this journal did not permit alterations in order to not influence the understanding of its contents.) It has already been 44 years (in 1997) since the armistice of the Korean War, but as for the worldwide sensation of 1952: how indisputable is the bacteriological war of the American imperialists? The case is one of false alarm. That year the Party Central Committee confirmed (at least at the beginning) that it believed that the U.S. Army was conducting bacteriological warfare. We mobilized the whole military and the whole nation, spending large amounts of manpower and materiel to carry out an anti- bacteriological warfare movement. At the same time, American imperialism was also notoriously reaching a low point. When the former commander of U.S. Forces in Korea, [Matthew Bunker] Ridgeway, was transferred to Allied Headquarters Europe at the end of 1952, crowds jeered him at his arrival to the airport, calling him “the god of pestilence”[1] and causing him embarrassment. -

Agricultural Production Situation in DPR Korea: 2020

Agricultural Production Situation in DPR Korea: 2020 Bir C. Mandal Deputy FAO Representative and Indrajit Roy International Consultant FAO Office in DPR Korea March 2020 Prepared: 31 March 2021 Content Page 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… ........................................ 3 2. Weather conditions………………………………………………….. ......................................................... 3 3. Early season planting ………………………………………………………. .................................................. 4 4. Main season planting…………………………………………………………………………… ............................ 5 5.. Crop production in 2020……………………………………………………………………………………. .............. 6 5.1. Rice……………………………………………………………….. ................................................................. 7 5.2. Maize…………………………………………………………. ..................................................................... 9 5.3 Potato ...................................................................................................................... 10 5.4 Soybean ...................................................................................................................... 12 5.5 Wheat and barley 13 5.6 Vegetables 15 6. Input use 16 7. Food supply/demand balance in 2020/2021 17 8. Conclusion 19 2 Prepared: 31 March 2021 Agricultural production situation in DPR Korea: 2020 Bir C. Mandal1 Indrajit Roy2 1. Introduction The year 2020 was extremely challenging for DPRK’s agriculture. In the wake of the outbreak of COVID- 19 epidemic in neighbouring China in December 2019, DPR Korea acted swiftly -

And the Korea of Jeong Dojeon (1342~1398) and Heo Gyun (1569~1618)

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 The Incomplete Social Contract: Elites and Ideals in the England of John Locke (1632~1704) and the Korea of Jeong Dojeon (1342~1398) and Heo Gyun (1569~1618) Jihyeong Park Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Asian History Commons, European History Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Park, Jihyeong, "The Incomplete Social Contract: Elites and Ideals in the England of John Locke (1632~1704) and the Korea of Jeong Dojeon (1342~1398) and Heo Gyun (1569~1618)" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 106. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/106 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Incomplete Social Contract: Elites and Ideals in the England of John Locke (1632~1704) and the Korea of Jeong Dojeon (1342~1398) and Heo Gyun (1569~1618) Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Jihyeong (Jonas) Park Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Senior Project Advisor Gregory B. -

Administrative Division, Natural Environment, Society & Economy

Research Note No. 803 52.9 77.7 125.6 155.7 231.7 357.1 381.5 402.1 343.5 378 431.7 445.7 435.7 437.6 459.6 457.5 464.6 477.3 488.7 501.9 550.7 69.2 573.6 575.3 572.2 567.8 586 78.6 108.1 129.4 116.8 76.5 Administrative Division, Natural Environment, Society & Economy 67.1 64.7 59.6 65 72.3 70.5 72.1 I. Administrative Division Current Status 〇 Administrative division system of North Korea: Jagang Province 1 directly governed city, 2 special cities, and 9 provinces - 1 directly governed city: Pyongyang Directly Governed City - 2 special cities: Rason Special City, Nampho Special City - 9 provinces: South Hwanghae Province, North Hwanghae Province, Kangwon Province, Sinuiju South Phyongan Province, North Phyongan Province, South Hamgyong Province, North Phyongan Province North Hamgyong Province, Jagang Province, Ryanggang Province * Kaesong City belongs to North Hwanghae Province South Phyongan Province Phyongsong At the time of liberation in 1945, the administrative divisions consisted of 6 dos, 9 sis, 89 guns, and 810 eup and myeons. In December 1952 during the Korean War, North Korea extensively reformed the administrative divisions by reducing Pyongyang Directly Governed City Pyongyang the four layers of do-gun-myeon-ri to three layers of do-gun-ri by abolishing myeon. Nampho Special City This reformed structure is still effective today. Nampho North Hwanghae Province Sariwon South Hwanghae Province Haeju Area and Population by Region Table 1. Area and population by region of South and North Koreas (Area: as of 2016 for South and North -

Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(S) Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours

Robert Winstanley-Chesters Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(s) Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Robert Winstanley-Chesters Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(s) Robert Winstanley-Chesters University of Leeds Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK ISBN 978-981-15-0041-1 ISBN 978-981-15-0042-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0042-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adap- tation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publi- cation does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Pdf | 422.85 Kb

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY http://www.goodfriends.or.kr/[email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.407 (Released in Korean on June 15, 2011) [“Good Friends” aims to help the North Korean people from a humanistic point of view and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as accurately as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ Editor’s Note: “Increasing Food Production - can Farm Mobilization be the Solution?” All-out Mobilization for Farm Villages, the Arduous War at its Peak “How can I Offer Help when I cannot even Feed Myself?” Power and Wealth, a License to Flee the Reach of Farming Mobilization Potatoes Stolen by Soldiers before they are Ripe The Spring Hardship Season Hits the Soldiers in the Forefront Areas Kkotjebis (Homeless Children) in Harsh Environment even in Collective Farms ________________________________________________________________________ Editor’s Note: “Increasing Food Production - can Farm Mobilization be the Solution?” “Farming is the lifeline in resolving people’s livelihood problems” - it sounds quite heavy. Farming, which is supposed to support the people, becomes the main frontline where they risk their lives. It’s time for the rice planting battle again and residents are dragging themselves to farms with a sigh of dismay. All family members, from little students to parents, become combatants in the farm mobilization combat. With more than 80% of the population assisting in farming, total crop yields still fall short of total rations. We hope that South and North Korea can cooperate and resolve the issues in the near future.