Two Nation States in the Korean Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

The Insect Database in Dokdo, Korea: an Updated Version Includes 22 Newly Recorded Species on the Island and One Species in Korea

PREPRINT Posted on 14/12/2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3897/arphapreprints.e62027 The Insect database in Dokdo, Korea: An updated version includes 22 newly recorded species on the island and one species in Korea Jihun Ryu, Young-Kun Kim, Sang Jae Suh, Kwang Shik Choi Not peer-reviewed, not copy-edited manuscript. Not peer-reviewed, not copy-edited manuscript posted on December 14, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3897/arphapreprints.e62027 The Insect database in Dokdo, Korea: An updated version includes 22 newly recorded species on the island and one species in Korea Jihun Ryu‡,§, Young-Kun Kim |, Sang Jae Suh|, Kwang Shik Choi‡,§,¶ ‡ School of Life Science, BK21 Plus KNU Creative BioResearch Group, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea § Research Institute for Dok-do and Ulleung-do Island, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea | School of Applied Biosciences, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea ¶ Research Institute for Phylogenomics and Evolution, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea Corresponding author: Kwang Shik Choi ([email protected]) Abstract Background Dokdo, an island toward the East Coast of South Korea, comprises 89 small islands. Dokdo is a volcanic island created by a volcanic eruption that promoted the formation of Ulleungdo (located in the East sea), which is ~87.525 km away from Dokdo. Dokdo is an important island because of geopolitics; however, because of certain investigation barriers such as weather and time constraints, the awareness of its insect fauna is less compared to that of Ulleungdo. Dokdo’s insect fauna was obtained as 10 orders, 74 families, and 165 species until 2017; subsequently, from 2018 to 2019, 23 unrecorded species were discovered via an insect survey. -

60 Chapter V Conclusion and Recommendation for The

60 CHAPTER V CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION FOR THE FUTURE OF JKFTA AND BOTH NATIONS The research question raised at the beginning challenges us to start contemplating in a different way than the usual. JKFTA has brought its own attention for its surprise appearance. But then scholars, business enthusiasts, and everyone else is presented by a delayed agreement. We have two important yet sensitive problems at our hand alongside with a postponed economic agreement, which initially, does not strike to be relevant to each other. But at the end of this research, there is a concrete happening between the two variables. The economic agreement has indeed postponed by the remaining historical disputes. At the very start, the birth of the notorious territorial dispute that is Liancourt Rocks is examined. The Liancourt Rocks is more than just mere islets. The islets are centuries old with many versions of the history of how it is found and many controversial debates for its ownership and value. Starting from ocean floor research, environmental research in general, military value, and then ended with the case of dignity. Past colonialism has indeed brought more and more bad impression to the people, making Liancourt Rocks as disputed today as it is in former times. Continuing with the matter of comfort women, nothing has been easier in the journey of this problem. It is also peaked at World War II, with many testimonies appearing in the Korean peninsula particularly Republic of Korea (ROK). It successfully garnered attention and pity. Victims began to be more ambitious in sharing their stories and demanding an apology from Japan’s government. -

The Case of Dokdo

Resolution of Territorial Disputes in East Asia: The Case of Dokdo Laurent Mayali & John Yoo* This Article seeks to contribute to solving of the Korea-Japan territorial dispute over Dokdo island (Korea)/Takeshima (Japanese). The Republic of Korea argues that Dokdo has formed a part of Korea since as early as 512 C.E.; as Korea currently exercises control over the island, its claim to discovery would appear to fulfill the legal test for possession of territory. Conversely, the Japanese government claims that Korea never exercised sufficient sovereignty over Dokdo. Japan claims that the island remained terra nullius—in other words, territory not possessed by any nation and so could be claimed—until it annexed Dokdo in 1905. Japan also claims that in the 1951 peace treaty ending World War II, the Allies did not include Dokdo in the list of islands taken from Japan, which implies that Japan retained the island in the postwar settlement. This article makes three contributions. First, it brings forward evidence from the maps held at various archives in the United States and Western Europe to determine the historical opinions of experts and governments about the possession of Dokdo. Second, it clarifies the factors that have guided international tribunals in their resolution of earlier disputes involving islands and maritime territory. Third, it shows how the claim of terra nullius has little legitimate authority when applied to East Asia, an area where empires, kingdoms, and nation-states had long exercised control over territory. * Laurent Mayali is the Lloyd M. Robbins Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law; John Yoo is the Emanuel S. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

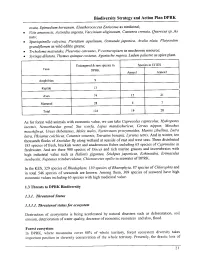

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Korea's Economy

2014 Overview and Macroeconomic Issues Lessons from the Economic Development Experience of South Korea Danny Leipziger The Role of Aid in Korea's Development Lee Kye Woo Future Prospects for the Korean Economy Jung Kyu-Chul Building a Creative Economy The Creative Economy of the Park Geun-hye Administration Cha Doo-won The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses KOREA Robert D. Atkinson Spurring the Development of Venture Capital in Korea Randall Jones ’S ECONOMY VOLUME 30 Economic Relations with Europe KOREA’S ECONOMY Korea’s Economic Relations with the EU and the Korea-EU FTA apublicationoftheKoreaEconomicInstituteof America Kang Yoo-duk VOLUME 30 and theKoreaInstituteforInternationalEconomicPolicy 130 years between Korea and Italy: Evaluation and Prospect Oh Tae Hyun 2014: 130 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Korea and Italy Angelo Gioe 130th Anniversary of Korea’s Economic Relations with Russia Jeong Yeo-cheon North Korea The Costs of Korean Unification: Realistic Lessons from the German Case Rudiger Frank President Park Geun-hye’s Unification Vision and Policy Jo Dongho Kor ea Economic Institute of America Korea Economic Institute of America 1800 K Street, NW Suite 1010 Washington, DC 20006 KEI EDITORIAL BOARD KEI Editor: Troy Stangarone Contract Editor: Gimga Group The Korea Economic Institute of America is registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the Government of the Republic of Korea. This material is filed with the Department of Justice, where the required registration statement is available for public inspection. Registration does not indicate U.S. -

A Teacher's Guide to Teaching About Korea in the U.S

A Teacher’s Guide to Teaching about Korea in the U.S. Edited by Young-Key Kim-Renaud, Ph.D. December 2016 A Teacher’s Guide to Teaching about Korea in the U.S. Edited by Young-Key Kim-Renaud, Ph.D. GWIKS (George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies) Working Papers, No. 1 Printed in Washington, DC, U.S.A. December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Young-Key Kim-Renaud This work was supported in part by the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016- OLU-2250009). 1 Table of Contents Preface 3 4 Author Profile 5 Part I • Young-Key Kim-Renaud, “Teaching about Korea: An Overview of Korean History and Culture” 6 Part II • Joseph (Jay) Harmon, “Korea in AP World History Textbooks: Perspectives” 66 • David A. Libardoni, “What I Learned about Korea through Teaching There” 72 • Megan Siczek, “Korea through Multiple Lenses” 75 • Daniel J. Whalen, “Dixie and the East Sea: The Impact of Nationalism on Place Names and Cultural Identities” 86 2 Preface This volume contains papers and power point presentations in English on Korea, which were delivered to pre-college level US educators in the Washington, DC Metropolitan area and visitors from elsewhere on two different occasions in 2016.* The first part is a slightly revised version of a brief overview of Korea and Korean history and culture, which was presented at the 2016 Fairfax County (VA) Public Schools Staff Development Day on August 31, 2016. -

The Insect Database in Dokdo, Korea: an Updated Version in 2020

Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e62011 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.9.e62011 Data Paper The Insect database in Dokdo, Korea: An updated version in 2020 Jihun Ryu‡,§, Young-Kun Kim |, Sang Jae Suh|, Kwang Shik Choi‡,§,¶ ‡ School of Life Science, BK21 FOUR KNU Creative BioResearch Group, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea § Research Institute for Dok-do and Ulleung-do Island, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea | School of Applied Biosciences, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea ¶ Research Institute for Phylogenomics and Evolution, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea Corresponding author: Kwang Shik Choi ([email protected]) Academic editor: Paulo Borges Received: 14 Dec 2020 | Accepted: 20 Jan 2021 | Published: 26 Jan 2021 Citation: Ryu J, Kim Y-K, Suh SJ, Choi KS (2021) The Insect database in Dokdo, Korea: An updated version in 2020. Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e62011. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.e62011 Abstract Background Dokdo, a group of islands near the East Coast of South Korea, comprises 89 small islands. These volcanic islands were created by an eruption that also led to the formation of the Ulleungdo Islands (located in the East Sea), which are approximately 87.525 km away from Dokdo. Dokdo is important for geopolitical reasons; however, because of certain barriers to investigation, such as weather and time constraints, knowledge of its insect fauna is limited compared to that of Ulleungdo. Until 2017, insect fauna on Dokdo included 10 orders, 74 families, 165 species and 23 undetermined species; subsequently, from 2018 to 2019, we discovered 23 previously unrecorded species and three undetermined species via an insect survey. -

Title : Across the East Sea Name : Ardhyana Rokhmahpratiwi Nationality : Indonesia

Title : Across the East Sea Name : Ardhyana Rokhmahpratiwi Nationality : Indonesia “Takeshima!” Mr. Kim Gyeong-jun was stunned at me for uttering this word. He stayed silent for a while and then with a sullen look, said to me in Korean, "Never use that name, Nana! The islets are called Dokdo not Takeshima." Kim is also a student to me as I teach him Indonesian. His statement was clear enough. I knew about the dispute between South Korea and Japan over the tiny islets situated in the East Sea. The two major East Asian economic powers each claim the islets as theirs. The islets, known internationally as ‘The Lian Court Rocks,' are called Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese. What I didn't know was that the mere mention of Takeshima would infuriate a Korean person. Only recently I've become aware of Koreans' exceptional patriotism toward the Dokdo Islets. Dokdo, consisting of two main coral islands, holds a special place in the Korean heart as it's symbolic of Korea's sovereignty, its people and its independence. Moreover, it was none other than Japan that once colonized the Korean Peninsula in the 1900s and is now claiming territorial rights to Dokdo. Dokdo is much more than just land to the Korean people. Dokdo is comprised of the two main East (Dongdo) and West (Seodo) Islands as well as 90 islets and reefs. It's 87 kilometers away from Ulleung Island in the East Sea. The Korean government has exerted numerous efforts to advocate Dokdo as Korean territory. It issued stamps bearing an image of the islets in the year 1940 and published an ad on the cover of New York Times stating that Dokdo belongs to Korea. -

Sustainability Report 2008 Sustainability Report 2008 About the Sustainability Report

Sustainability Report 2008 Sustainability Report 2008 About the Sustainability Report Introduction and Structure Reporting Period Korea Land Corporation, since its establishment in 1975, has been committed to develop- This report illustrates our sustainability management activities and performance from ing the national economy and improving the public welfare. Today, we are doing our August 1 of 2006 to December 31 of 2007. Our first Sustainability Report was issued in best to take good care of our precious land resources which we share with our successive 2005, which describes our sustainability management for the calendar year 2004 and generations, keeping in mind the philosophy that we serve as a "National Land the <Sustainability Report 2008> is our third Sustainability Report which illustrates our Gardener". economic, environmental and social progress and our commitment to corporate social responsibility management. This report contains Our corporate strategies, systems, activities and performance in each of the three pillars of sustainability management: economy, environment and society. Scope and Limitations Data used in this report cover performance of all of our offices at home and abroad and Improvements from our Earlier Sustainability Report were collated as of December 31 of 2007 unless stated otherwise. Most data present This report responds to feedback from our external stakeholders including NGOs (the Center time-series trends of at least three years and denominated in Korean won. for Corporate Responsibility) and academia on our <Sustainability Report 2006>(published in December, 2006) in the following areas External Assurance -we made sure that this report specifies whether it satisfies reporting guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and duly describes our commitment to sustainability management. -

From Pacifism to Proactive Policies Between 1976- 2018

TRANSFORMATION OF JAPANESE SECURITY POLICY: FROM PACIFISM TO PROACTIVE POLICIES BETWEEN 1976- 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY VUSLAT NUR ŞAHİN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AUGUST 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sadettin Kirazcı Director (Acting) I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Oktay Fırat Tanrısever Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Şerif Onur Bahçecik (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Assist. Prof. Dr. Hatice Çelik (Kırıkkale Uni., Uİ) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Vuslat Nur Şahin Signature : iii ABSTRACT TRANSFORMATION OF JAPANESE SECURITY POLICY: FROM PACIFISM TO PROACTIVE POLICIES BETWEEN 1976- 2018 Şahin, Vuslat Nur MSc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı July 2019, 111 pages This thesis examines Japan’s security policy, with particular focus on relations with East Asian countries and the US, especially consider the policy changes in security from pacifism to proactive.