Ancient Astrology As a Common Root for Science and Pseudo-Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquarius Aries Pisces Taurus

Zodiac Constellation Cards Aquarius Pisces January 21 – February 20 – February 19 March 20 Aries Taurus March 21 – April 21 – April 20 May 21 Zodiac Constellation Cards Gemini Cancer May 22 – June 22 – June 21 July 22 Leo Virgo July 23 – August 23 – August 22 September 23 Zodiac Constellation Cards Libra Scorpio September 24 – October 23 – October 22 November 22 Sagittarius Capricorn November 23 – December 23 – December 22 January 20 Zodiac Constellations There are 12 zodiac constellations that form a belt around the earth. This belt is considered special because it is where the sun, the moon, and the planets all move. The word zodiac means “circle of figures” or “circle of life”. As the earth revolves around the sun, different parts of the sky become visible. Each month, one of the 12 constellations show up above the horizon in the east and disappears below the horizon in the west. If you are born under a particular sign, the constellation it is named for can’t be seen at night. Instead, the sun is passing through it around that time of year making it a daytime constellation that you can’t see! Aquarius Aries Cancer Capricorn Gemini Leo January 21 – March 21 – June 22 – December 23 – May 22 – July 23 – February 19 April 20 July 22 January 20 June 21 August 22 Libra Pisces Sagittarius Scorpio Taurus Virgo September 24 – February 20 – November 23 – October 23 – April 21 – August 23 – October 22 March 20 December 22 November 22 May 21 September 23 1. Why is the belt that the constellations form around the earth special? 2. -

Notes on Contributors

Notes on Contributors Giuseppe Bezza teaches the history of science and technology at Ravenna (University of Bologna). He has written a number of essays on the history of astrology. He is the author of Commento al primo libro della Tetrabiblos di Claudio Tolemeo (Milan, 1991), Arcana Mundi. Antologia del pensiero astrologico classico (Milan, 1995) and Précis d’historiographie de l’astrologie: Babylone, Égypte, Grèce (Turnhout, 2003). Joseph Crane studied philosophy at Brandeis and has professional training as a psychotherapist. He has practiced astrology and taught astrological and consulting skills since the late 1980s. He began learning traditional astrology in the early 1990s and since then has brought it into his teaching and consulting practice. He lectures on ancient and modern astrological techniques as well as connecting astrology with works of literature and philosophy. He is the author of Astrological Roots: The Hellenistic Tradition (Bournemouth, 2007), a presentation of Hellenistic astrology to modern astrologers, and A Practical Guide to Traditional Astrology (Reston, VA, 1997/2006). Website: www.astrologyinstitute.com. Susanne Denningmann studied Classics and Philosophy at the University of Münster. From 2000 to 2003 she was a research assistant at the collaborative research centre, Functions of Religion in Ancient Near Eastern Societies, supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), where she focussed on ancient astrology. She received her PhD in Classics and Philosophy in 2004 at the University of Münster. The subject of her thesis was the astrological doctrine of doryphory, published in 2005 as Die astrologische Lehre der Doryphorie. Eine soziomorphe Metapher in der antiken Planetenastrologie (Beiträge zur Altertumskunde, 214). -

Taoist Ways to Transorm You Life

Special Taoist Healing Arts Retreat December 16-22, 2012 Taoist Ways to Transform Your Life Grandmaster Mantak Chia & Dr. David Twicken Chinese Astrology Qi Gong Inner Alchemy Feng Shui Qi Men Dun Jia 30-CEUs approved by the California Acupuncture Board and accepted by NCCAOM Join Grandmaster Mantak Chia and Dr. David Twicken in the magnificent mountains of Thailand for a special Taoist healing retreat. At the foothill of the Himalayan mountains is an oasis called Tao Garden. Its purpose is to provide a place for people from all the world to learn and practice healing arts to enhance their physical, emotional and spiritual well being in a natural and supportive setting. Supported by clean mountain air, natural water, organic fruits and vegetables and like- minded people, this retreat is a unique opportunity to increase your vitality and health with the Taoist healing arts. The ancient Chinese understood the inseparable nature of heaven, humanity and earth and called this unity the Three Treasures. In this unique workshop Grandmaster Chia and Dr. Twicken will present how to use Taoist practices to enhance your three treasures: your physical, emotional and spiritual life. You will learn about a Chinese Astrology birth chart and natural healing methods to balance your body, mind and spirit. The Chinese astrology chart, which is called the four pillars, is a roadmap of your life. This workshop is for anybody that would like to learn how to use Taoist healing methods for self-healing and healing others. Chinese astrology reflects the heaven treasure. It is a blueprint of your life. -

ANCIENT ASTROLOGY in the Tradition of Enmeduranki Hermes

pάnta7pᾶsi ‘PLACIDUS RESEARCH CENTER’ www.babylonianastrology.com; [email protected] Nov 3-8, 2011, Varna, Bulgaria Arahsamna 6-11 (spring equinox in Addaru system) ANCIENT ASTROLOGY in the tradition of Enmeduranki Hermes. PLACIDUS version 7.0 with PORPHYRIUS MAGUS version 2.0- FIRST RECONSTRUCTION of THE ANCIENT ASTROLOGY as it existed in 5,500 BC to 300 BC 1 THE ELEMENTS OF ANCIENT ASTROLOGY in TWO DIMENSIONS In Placidus 7, with Porphyrius Magus version 2, are coming, for the first time, elements of the most Ancient Astrology, which was practiced in Mesopotamia from 5,500 BC to 70 AD and which, according to the tradition, is coming directly from the illumination of the first Hermes, the prophet Enoh, Lord Enmeduranki from pre-diluvial Sippar in 5,500 BC. Being behind the mist of 7,500 years, we can see but only the outlines of that Original Astral Revelation. However, drawing from Akkadian texts, we can completely recreate the last reconstruction made by the third Hermes in around 770 BC. To recreate ancient Astrology, the program projects the celestial sphere with the Ecliptical Pole in the center. In this way, the ecliptic is a perfect circle and we see the ascendant on the left (if we choose the South Pole as center). This is our well known astrological chart, but in 2 dimensions. The first element,the fixed Babylonian zodiac, as re-created and registered by the third Hermes, from around 770 BC, with its 12 images, stars and exact borders is shown below (the basis of the dating to 770 BC is coming from a work to be published, in my complete translation and comments of the , for the major part, untranslated until now Akkadian astral text LBAT 1499). -

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures Edited by Markus Asper Philip van der Eijk Markham J. Geller Heinrich von Staden Liba Taub Volume 3 In the Wake of the Compendia Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia Edited by J. Cale Johnson DE GRUYTER ISBN 978-1-5015-1076-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-5015-0250-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0252-1 ISSN 2194-976X Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Typesetting: Meta Systems Publishing & Printservices GmbH, Wustermark Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Notes on Contributors Florentina Badalanova Geller is Professor at the Topoi Excellence Cluster at the Freie Universität Berlin. She previously taught at the University of Sofia and University College London, and is currently on secondment from the Royal Anthropological Institute (London). She has published numerous papers and is also the author of ‘The Bible in the Making’ in Imagining Creation (2008), Qurʾān in Vernacular: Folk Islam in the Balkans (2008), and 2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch: Text and Context (2010). Siam Bhayro was appointed Senior Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies in the Department of Theology and Religion, University of Exeter, in 2012, having previously been Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies since 2007. -

The Zodiac: Comparison of the Ancient Greek Mythology and the Popular Romanian Beliefs

THE ZODIAC: COMPARISON OF THE ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND THE POPULAR ROMANIAN BELIEFS DOINA IONESCU *, FLORA ROVITHIS ** , ELENI ROVITHIS-LIVANIOU *** Abstract : This paper intends to draw a comparison between the ancient Greek Mythology and the Romanian folk beliefs for the Zodiac. So, after giving general information for the Zodiac, each one of the 12 zodiac signs is described. Besides, information is given for a few astronomical subjects of special interest, together with Romanian people believe and the description of Greek myths concerning them. Thus, after a thorough examination it is realized that: a) The Greek mythology offers an explanation for the consecration of each Zodiac sign, and even if this seems hyperbolic in almost most of the cases it was a solution for things not easily understood at that time; b) All these passed to the Romanians and influenced them a lot firstly by the ancient Greeks who had built colonies in the present Romania coasts as well as via commerce, and later via the Romans, and c) The Romanian beliefs for the Zodiac is also connected to their deep Orthodox religious character, with some references also to their history. Finally, a general discussion is made and some agricultural and navigator suggestions connected to Pleiades and Hyades are referred, too. Keywords : Zodiac, Greek, mythology, tradition, religion. PROLOGUE One of their first thoughts, or questions asked, by the primitive people had possibly to do with sky and stars because, when during the night it was very dark, all these lights above had certainly arose their interest. So, many ancient civilizations observed the stars as well as their movements in the sky. -

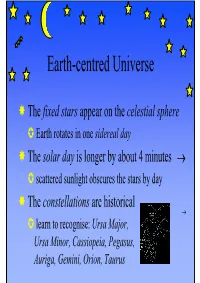

Earth-Centred Universe

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018

1 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Benjamin Franklin,Watson & Crick, Rosalind Franklin, Galileo Galilei, Dr. Linus Pauling, William Crawford Eddy, James Watt Maria Goeppert-Mayer, Charles Darwin, James Clerk Maxwell, Archimedes, Lise Meitner, Sigmund Freud, Irène Joliot-Curie Gregor Johann Mendel,Chien-Shiung Wu,Barbara McClintock, Neil DeGrasse Tyson. All Contents ©2017 Photo Researchers, Inc., 307 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY , 10016 212-758-3420 800-833- 9033 Science Source® is a registered trademark of Photo Researchers, Inc. / 2 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Course Data PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science >2 4.00 cr. Grading Options: Optional for all students Instructor: Prof. N. Zack, Office: 239 SCH Phone: (541) 346-1547 Office Hours: WTh -2-3 See CRN for CommentsPrereqs/Comments: Prereq: one philosophy course (waiver available) *Note: This is a 2-hr course twice a week and discussion is built in. There will breaks and variations in subject matter to keep it interesting. OVERVIEW/DESCRIPTION (See also APPENDICES A-D AFTER SYLLABUS) Philosophy of Science is unique to philosophy. It raises questions about facts, theories, reality, explanation, and truth not often addressed by scientists or other humanistic scholars. This course will provide the basics of Philosophy of Science with concrete examples as science now applies to contemporary subjects such as Climate Change, Feminism, and Race. Students will have an opportunity to choose their own branches of inquiry for end-of-term reports. Work will consist of reading, discussion, and 4 3-page papers. -

A History of Western Astrology: Ancient World V. 1 Free Download

A HISTORY OF WESTERN ASTROLOGY: ANCIENT WORLD V. 1 FREE DOWNLOAD Nicholas Campion | 400 pages | 16 Jun 2009 | Continuum Publishing Corporation | 9781441127372 | English | New York, United States A History of Western Astrology Volume I The earliest calendars were employed by peoples such as the Zapotecs and Olmecsand later by such peoples as the MayaMixtec and Aztecs. Unread book in perfect condition. Over the course of the year, each constellation rose just before sunrise for ten days. Skip to content — Astrologer Tsou Yen lived around BC, and wrote: "When some new dynasty is going to arise, heaven exhibits auspicious signs for the people". Satisfaction Guaranteed! Archived from the original on 5 May Campion challenges the idea that astrology was invented by the Greeks, and asks whether its origins lie in Near-Eastern religion, or whether it can be considered a decadent Eastern import to the west. Seller Inventory AAV Paperback or Softback. Canberra1. Keith Thomas writes that although heliocentrism is consistent with astrology theory, 16th and 17th century astronomical advances meant that "the world could no longer be envisaged as a compact inter-locking organism; it was now a mechanism of infinite dimensions, from which the hierarchical subordination of earth to heaven had irrefutably disappeared". Astrologers by nationality List of astrologers. Seller Inventory x Ancient World Paperback Books. Astrology in seventeenth century England was not a science. Lofthus, Myrna Astrologers noted these constellations and so attached a particular significance to them. Who are these people to tell Indians — the inheritors of the only surviving civilization of the ancient world — how they Brand new Book. -

Paranormal Beliefs: Using Survey Trends from the USA to Suggest a New Area of Research in Asia

Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 279 Vol. 2 No.4 August 2015: 279-306 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2015.2.4.279 Paranormal Beliefs: Using Survey Trends from the USA to Suggest a New Area of Research in Asia Jibum Kim1 Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea Cory Wang Nick Nuñez NORC at the University of Chicago, USA Sori Kim Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea Tom W. Smith NORC at the University of Chicago, USA Neha Sahgal Pew Research Center, USA Abstract Americans continue to have beliefs in the paranormal, for example in UFOs, ghosts, haunted houses, and clairvoyance. Yet, to date there has not been a systematic gathering of data on popular beliefs about the paranormal, and the question of whether or not there is a convincing trend in beliefs about the paranormal remains to be explored. Public opinion polling on paranormal beliefs shows that these beliefs have remained stable over time, and in some cases have in fact increased. Beliefs in ghosts (25% in 1990 to 32% in 2005) and haunted houses (29% in 1990, 37% in 2001) have all increased while beliefs in clairvoyance (26% in 1990 and 2005) and astrology as scientific (31% in 2006, 32% in 2014) have remained stable. Belief in UFOs (50%) is highest among all paranormal beliefs. Our findings show that people continue to hold beliefs about the paranormal despite their lack of grounding in science or religion. Key Words: Paranormal beliefs, ghosts, astrology, UFOs, clairvoyance 1 All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jibum Kim at Department of Sociology, Sungkyunkwan University, 25-2 Sungkyunkwan-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-745, Republic of Korea or by email at [email protected]. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas.