Registration Test Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland

REPORT TO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES REGIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT (RID), NORTH REGION ON An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland Volume 1 February 1999 Peter Wilson (Land Resource Officer, Land Information Management) Seonaid Philip (Senior GIS Technician) Department of Natural Resources Resource Management GIS Unit Centre for Tropical Agriculture 28 Peters Street, Mareeba Queensland 4880 DNRQ990076 Queensland Government Technical Report This report is intended to provide information only on the subject under review. There are limitations inherent in land resource studies, such as accuracy in relation to map scale and assumptions regarding socio-economic factors for land evaluation. Before acting on the information conveyed in this report, readers should ensure that they have received adequate professional information and advice specific to their enquiry. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report neither the Queensland Government nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result from any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. © State of Queensland 1999 For information about this report contact [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors thank the input of staff of the Department of Natural Resources GIS Unit Mareeba. Also that of DNR water resources staff, particularly Mr Jeff Benjamin. Mr Steve Ockerby, Queensland Department of Primary Industries provided invaluable expertise and advice for the development of the agricultural suitability assessment. Mr Phil Bierwirth of the Australian Geological Survey Organisation (AGSO) provided an introduction to and knowledge of Airborne Gamma Spectrometry. Assistance with the interpretation of AGS data was provided through the Department of Natural Resources Enhanced Resource Assessment project. -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

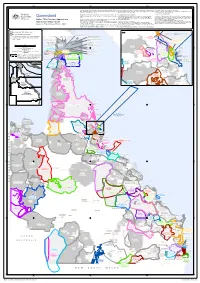

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

IR 519 Preliminary Analysis of Streamflow Characteristics of The

internal report 519 Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region DR Moliere February 2007 (Release status - unrestricted) Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region DR Moliere Hydrological and Geomorphic Processes Program Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist Supervising Scientist Division GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 February 2007 Registry File SG2006/0061 (Release status – unrestricted) How to cite this report: Moliere DR 2007. Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region. Internal Report 519, February, Supervising Scientist, Darwin. Unpublished paper. Location of final PDF file in SSD Explorer \Publications Work\Publications and other productions\Internal Reports (IRs)\Nos 500 to 599\IR519_TRR Hydrology (Moliere)\IR519_TRR hydrology (Moliere).pdf Contents Executive summary v Acknowledgements v Glossary vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Climate 2 2 Hydrology 5 2.1 Annual flow 5 2.2 Monthly flow 7 2.3 Focus catchments 11 2.3.1 Data 11 2.3.2 Data quality 18 3 Streamflow classification 19 3.1 Derivation of variables 19 3.2 Multivariate analysis 24 3.2.1 Effect of flow data quality on hydrology variables 31 3.3 Validation 33 4 Conclusions and recommendations 35 5 References 35 Appendix A – Rainfall and flow gauging stations within the focus catchments 38 Appendix B – Long-term flow stations throughout the tropical rivers region 43 Appendix C – Extension of flow record at G8140040 48 Appendix D – Annual runoff volume and annual peak discharge 52 Appendix E – Derivation of Colwell parameter values 81 iii iv Executive summary The Tropical Rivers Inventory and Assessment Project is aiming to categorise the ecological character of rivers throughout Australia’s wet-dry tropical rivers region. -

Aboriginal Men of High Degree Studiesin Sodetyand Culture

])U Md�r I W H1// <43 H1�hi Jew Jn• Terrace c; T LUCIA. .Id 4007 �MY.Ers- Drysdale R. 0-v Cape 1 <0 �11 King Edward R Eylandt J (P le { York Prin N.Kimb �0 cess Ch arlotte Bay JJ J J Peninsula Kalumbur,:u -{.__ Wal.cott • C ooktown Inlet 1r Dampier's Lan by Broome S.W.Kimberley E. Kimberley Hooker Ck. La Grange Great Sandy Desert NORTHERN TERRITORY Port Hedland • Yuendumu , Papanya 0ga Boulia ,r>- Haasts Bluff • ,_e':lo . Alice Springs IY, Woorabin Gibson Oesert Hermannsburg• da, �igalong pe ter I QU tn"' "'= EENSLAND 1v1"' nn ''� • Ayre's Rock nn " "' r ---- ----------------------------L- T omk i nson Ra. Musgrave Ra. Everard Ra Warburton Ra. WESTERN AUSTRALIA Fraser Is. Oodnadatta · Laverton SOUTH AUSTRALIA Victoria Desert New Norcia !) Perth N EW SOUT H WALES Great Australian Bight Port �ackson �f.jer l. W. llill (lr14), t:D, 1.\ Censultlf . nt 1\n·hlk.. l �st Tl·l: ( 117} .171-'l.lS Aboriginal Men of High Degree Studiesin Sodetyand Culture General Editors: Jeremy Beckett and Grant Harman Previous titles in series From Past4 to Pt�vlova: A Comp��rlltivt Study ofIlllli1111 Smlm m Sydney & Griffith by Rina Huber Aboriginal Men of High Degree SECOND EDITION A. P. Elkin THEUNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLANDLffiRARY SOCIALSCIENCES AND HUMANITIES LIBRARY University of Queensland Press First edition 1945 Second edition © University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1977 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no p�rt may be reproduced by any process without written permission. -

Western Queensland

Western Queensland - Gulf Plains, Northwest Highlands, Mitchell Grass Downs and Channel Country Bioregions Strategic Offset Investment Corridors Methodology Report April 2016 Prepared by: Strategic Environmental Programs/Conservation and Sustainability Services, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Letter of Transmittal

Queensland South Native Title Services ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion Minister for Indigenous Affairs Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 15 October 2015 Dear Minister, I am pleased to present the 2014 - 2015 Annual Report for Queensland South Native Title Services Limited (QSNTS). This report is provided in accordance with the Australian Government’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2013 - 2015 terms and conditions relating to the native title funding agreements under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), s203FE(1). The report includes independently audited financial statements for the financial year ending 30 June 2015. Thank you for your ongoing support of the work QSNTS strives to achieve. Yours sincerely, Board of Directors, Queensland South Native Title Services Diamantina Developmental Road, south of Herbert Downs Annual Report 2014 – 2015 | i TABLE OF CONTENTS Lettter of Transmittal ..................................................................................................................................................i Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................................01 Glossary ...................................................................................................................................................................02 Contact Details.......................................................................................................................................................03 -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the FLINDERS RIVER

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Flinders FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the FLINDERS RIVER This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Flinders River. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated January 2020) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Cloncurry River at Cloncurry Flood Risk The Flinders River catchment is located in north west Queensland and drains an area of approximately 109,000 square kilometres. The river rises in the Great Dividing Range, 110 kilometres northeast of Hughenden and flows initially in a westerly direction towards Julia Creek, before flowing north to the vast savannah country downstream of Canobie. It passes through its delta and finally into the Gulf of Carpentaria, 25 kilometres west of Karumba. The Cloncurry and Corella Rivers, its major tributaries, enter the river from the southwest above Canobie. There are several towns in the catchment including Hughenden, Richmond, Julia Creek and Cloncurry. Floods normally develop in the headwaters of the Flinders, Cloncurry and Corella Rivers. General heavy rainfall situations can develop from cyclonic influences in the Gulf of Carpentaria which cause widespread flooding, particularly in the lower reaches below Canobie. Previous Flooding Previous flood information for the Flinders Rivers is well documented. The towns of Hughenden, Richmond and Cloncurry have extensive peak height records dating back some 50 years. -

Surface Water Network Review Final Report

Surface Water Network Review Final Report 16 July 2018 This publication has been compiled by Operations Support - Water, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. © State of Queensland, 2018 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Interpreter statement: The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this document, you can contact us within Australia on 13QGOV (13 74 68) and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. Surface -

Three Rivers Irrigation Project Initial Advice Statement

Three Rivers Irrigation Project Initial Advice Statement June 2015 TRIP Initial Advice Statement: Stanbroke TRIP Initial Advice Statement: Stanbroke TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................................... I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. III 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1. Purpose and Scope of the Initial Advice Statement ................................................. 1 2. THE PROPONENT.................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Stanbroke Pty Ltd .............................................................................................................. 3 3. THE NATURE OF THE PROPOSAL ............................................................................................. 4 3.1. Scope of the Project .......................................................................................................... 4 3.1.1. Water Extraction ....................................................................................................... 4 3.1.2. Offstream Storages .................................................................................................. -

Agricultural Resource Assessment for the Flinders Catchment

Petheram C, Watson I and Stone P (eds) (2013) Agricultural resource assessment for the Flinders catchment. A report to the Australian Government from the CSIRO Flinders and Gilbert Agricultural Resource Assessment, part of the North Queensland Irrigated Agriculture Strategy. CSIRO Water for a Healthy Country and Sustainable Agriculture flagships, Australia. © CSIRO 2013 See <www.csiro.au/FGARA> for full report. Appendix C List of figures Figure 1.1 Major dams (greater than 500 GL capacity), large irrigation areas and selected drainage divisions across Australia .................................................................................................................................... 3 Figure 1.2 Schematic diagram of key components and concepts in the establishment of a greenfield irrigation development ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Figure 2.1 The Flinders and Gilbert catchments within the Gulf region of northern Australia ....................... 10 Figure 2.2 The Flinders catchment ................................................................................................................... 11 Figure 2.3 Soil sampling sites and airborne geophysical survey flight lines of the Flinders catchment .......... 14 Figure 2.4 Schematic representation of digital soil mapping method ............................................................. 15 Figure 2.5 Availability of rainfall data in the Flinders catchment .................................................................... -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1949

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly THURSDAY, 4 AUGUST 1949 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 36 Questions. [ASSEMBLY.] Questions. THURSDAY, 4 AUGUST, 1949. -to provide farms for 10 soldier settlers is approaching completion. Water will be pumped from the Burdekin River and sup The AC'l'I~G SPEAKER (The CHAIR plied by means of channels and pipelines MAN of COMMITTEES, Mr. Manu, Bris to the farms. The main crop will be bane) took the chair at 11 a.m. tobacco. The main Burdekin River Project of which the Clare scheme is a part, pro QUESTIONS. vides for the construction of a dam to a TULLY HYDRO-ELECTRIC SCHEME. height of 138 feet above the general level of the river bed for the provision of a llir. MAHER (West Moreton) asked the useful storage of 3,600,000 acre feet. Pre Secretary for Public Lands and Irrigation liminary designs for a mass concrete dam '' 1. Has any construction work yet been have been prepared. Preliminary contour commenced in connection with the Tully surveys for the Burdekin Project have been Falls scheme~ carried out for 100,000 acres of the 500,000 '' 2. What irrigation or hydro-electric acres of potentially irrigable lands esti schemes have reached the constructional mated to be available. Diamond drilling stage, indicating the locality, the estimated by the Mines Department is in hand at tot:;tl cost,_ the expenditure to date, and the the main storage dam site at the Burdekin mam obJects of each scheme, respec Falls. Surveys have been completed of tively~'' the ponded area, and aerial surveys of some 3,000,000 acres of the ponc1ed area and Hon. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court.