Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

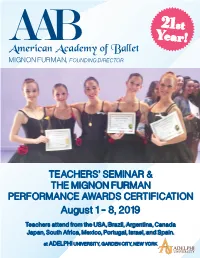

The Mignon Furman Performance Awards 1000S of Dancers!

21st AAB Year! American Academy of Ballet MIGNON FURMAN, FOUNDING DIRECTOR TEACHERS’ SEMINAR & THE MIGNON FUR MAN PERFORMANCE AWARDS CERTIFICATION August 1 – 8, 2019 Teachers attend from the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Canada Japan, South Africa, Mexico, Portugal, Israel, and Spain. at ADELPHI UNIVERSITY, GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK REASONS TO ATTEND THE SEMINAR Mignon Furman 10 AND THE PERFORMANCE AWARDS Founder of the AAB, Teacher, Choreographer, Educationist. CERTIFICATION EVERYTHING MOVES FORWARD. “ THEREFORE, I RECOMMEND: ith her talents, courage, and determination KEEP IN TOUCH WITH YOUR ART. to give definition to her vision for ballet PERFORMANCE AWARDS — AGRIPPINA VAGANOVA, ” Weducation, Mignon Furman founded the American and “Steps” programs. Most wonderful programs for “BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET” (1934) Academy of Ballet: It soon became the premier teachers and their dancers. (View the brochures on Summer School in the United States. our website.) he composed the Performance Awards S which are taught all over the USA, and are an CERTIFICATION : international phenomenon, praised by teachers Become a certified Performance Awards teacher. in the USA and in many other countries. The Hang your diploma in your studio. success of the Performance Awards is due to Mignon’s choreography: She was a superb choreographer. Her many compositions are FOUR DANCES : free of cliché. They have logic, harmony, style, To teach in your school. (See page 5.) and intrinsic beauty. OBSERVE : Our distinguished argot Fonteyn, a friend of Mignon, gave faculty teaching our Summer School dancers. her invaluable advice, during several You have the option of taking the classes. Mdiscussions about the technical, and artistic aspects of classical ballet. -

Technique: Battement Tendu Once Upon a Ballet™

Technique: Battement Tendu Once Upon A Ballet™ Tendus are done during “circle barre” or “centre barre” up through Pre-Ballet II. In Ballet 1, students begin performing tendus at the barre. RECOMMENDED PROGRESSION OF BATTEMENT TENDU: ● 2 year olds should be able to “tendu” with the help of a prop (such as a bean bag, mat or tape for them to point to with their toes). They may also need the help of a parent/caregiver. ● 3 year olds should be able to tendu to the front in parallel with correct posture. ● 4 years olds should be able to tendu to the front from a "slight V" 1st position with correct posture. ● 5 and 6 year olds should tendu front and side from a "natural" 1st position with correct posture. Students should be introduced to completing tendus at varying speeds. When done slowly, there should be emphasis placed on rolling through the demi pointe to close. ● 7 through 9 year olds should tendu to the front, side and back from 1st position. Tendus should be introduced in a slow tempo with emphasis placed on rolling through the demi pointe. Later in the year, students should also be introduced to tendu front, side and back from 5th position. AGE-APPROPRIATE IMAGES AND WORDS TO USE: ● To help students work through their feet correctly, use the word “slide” out and “slide” in for tendus. ● If telling your students to “straighten” their knees does not obtain results, try telling them to “stretch their legs long” or to “keep their knees stiff”. Sometimes using different language will click better with certain students. -

Ballet Terms Definition

Fundamentals of Ballet, Dance 10AB, Professor Sheree King BALLET TERMS DEFINITION A la seconde One of eight directions of the body, in which the foot is placed in second position and the arms are outstretched to second position. (ah la suh-GAWND) A Terre Literally the Earth. The leg is in contact with the floor. Arabesque One of the basic poses in ballet. It is a position of the body, in profile, supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind and at right angles to it, and the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line along the body. Attitude A pose on one leg with the other lifted in back, the knee bent at an angle of ninety degrees and well turned out so that the knee is higher than the foot. The arm on the side of the raised leg is held over the held in a curved position while the other arm is extended to the side (ah-tee-TEWD) Adagio A French word meaning at ease or leisure. In dancing, its main meaning is series of exercises following the center practice, consisting of a succession of slow and graceful movements. (ah-DAHZ-EO) Allegro Fast or quick. Center floor allegro variations incorporate small and large jumps. Allonge´ Extended, outstretched. As for example, in arabesque allongé. Assemble´ Assembled or joined together. A step in which the working foot slides well along the ground before being swept into the air. As the foot goes into the air the dancer pushes off the floor with the supporting leg, extending the toes. -

Academic Ballet: a National and Transnational Perspective

Dr. Svebor Sečak Assistant Professor, AMEU ACADEMIC BALLET: A NATIONAL AND TRANSNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE ABSTRACT Drawing on historical perspectives, the paper follows the main diachronic line of world ballet history, and from a broad perspective focuses on Slovenia and the concept of national ensembles that were dominant in 20th-century Europe. A real challenge for national companies emerges at the turn of the century, when national companies increasingly become transnational. The repertoire becomes eclectic, and the new readings of canonical works are susceptible to the concept of intertextuality, hybridisation of genres and co-mixing of cultural influences. The academic, scientific approach has a significant role in following this vivid and vibrant process in ballet art. It studies dance art from numerous analytical perspectives that sur- pass the acquiring of technical dancing skills and the factual history of dance but rather involve semiotics, anthropological, philosophical, psychoanalytical, socio-political and feminist and gender perspectives, as well as kinesiology, anatomy and physiology in the context of safe practice. In the previous academic year, Slovenia acquired its dance academy which offers studying and teaching of ballet on an entirely new lev- el. It produces not only future professionals, but indirectly facilitates the education of a wider population relating to the significance of dance for the culture of the 21st century. It will potentially secure a double result: the preservation of the autochthonic culture and tradition and the opening up to new tendencies and philosophies as an integrative factor within Europe and worldwide. Key words: ballet, dance academy, dance education, transnationality INTRODUCTION This text recognises the dichotomy between the concept of the so-called national ballet styles, scho- ols and companies and their international character that traverses into a fully transnational mode. -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by -

Miami City Ballet 37

Miami City Ballet 37 MIAMI CITY BALLET Charleston Gaillard Center May 26, 2:00pm and 8:00pm; Martha and John M. Rivers May 27, 2:00pm Performance Hall Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez Conductor Gary Sheldon Piano Ciro Fodere and Francisco Rennó Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra 2 hours | Performed with two intermissions Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1980) Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Music Charles Gounod Staging Ben Huys Costume Design Karinska Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Katia Carranza, Renato Penteado, Nathalia Arja Emily Bromberg, Ashley Knox Maya Collins, Samantha Hope Galler, Jordan-Elizabeth Long, Nicole Stalker Alaina Andersen, Julia Cinquemani, Mayumi Enokibara, Ellen Grocki, Petra Love, Suzette Logue, Grace Mullins, Lexie Overholt, Leanna Rinaldi, Helen Ruiz, Alyssa Schroeder, Christie Sciturro, Raechel Sparreo, Christina Spigner, Ella Titus, Ao Wang Pause Carousel Pas de Deux (1994) Choreography Sir Kenneth MacMillan Music Richard Rodgers, Arranged and Orchestrated by Martin Yates Staging Stacy Caddell Costume Design Bob Crowley Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Jennifer Lauren, Chase Swatosh Intermission Program continues on next page 38 Miami City Ballet Concerto DSCH (2008) Choreography Alexei Ratmansky Music Dmitri Shostakovich Staging Tatiana and Alexei Ratmansky Costume Design Holly Hynes Lighting Design Mark Stanley Dancers Simone Messmer, Nathalia Arja, Renan Cerdeiro, Chase Swatosh, Kleber Rebello Emily Bromberg and Didier Bramaz Lauren Fadeley and Shimon Ito Ashley Knox and Ariel Rose Samantha -

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

Festivals and Occasions People Premieres

Dutch National Ballet - Daniel Camargo and Igone de Jongh in John Neumeier's La Dame aux Camélias. © Emma Kauldhar Contents In 2018 we are celebrating People 74 Crystal Palace th our 40 Anniversary! CATHERINE PAWLICK takes in a spectacular 10 Mathias Dingman production at the Kremlin Palace Theatre 40 YEARS VIKI WESTALL meets Birmingham Royal Ballet's in Moscow nurturing students towards American principal dancer professional careers Festivals and 40 YEARS 26 Mark Morris Occasions inspiring dancers and audiences AMANDA JENNINGS interviews the inimitable alike with exciting repertoire choreographer in New York 44 Le Temps d'Aimer FRANÇOIS FARGUE on the diverse programme offered by the unique festival in Biarritz 40 YEARS 48 Katja Khaniukova gracing the stage of Munich’s EMMA KAULDHAR catches up with ENB's legendary National Theatre 64 Carlos Acosta - A Celebration Ukrainian soloist in Kiev ROBERT PENMAN weighs up the Cuban's programme to celebrate 30 years on stage 66 Lorenzo Trossello MIKE DIXON meets Northern Ballet's 70 Umbrella 2018 Today the Foundation manages young Italian dancer GERARD DAVIS picks some of the Germany’s largest junior compa- contemporary dance festival's highlights ny: the Bayerisches Junior Ballett Premieres München. We look forward to 78 Joaquin De Luz Farewell welcoming you at a performance Remembrance LUCY VAN CLEEF watches the NYCB in the near future. 22 principal step down in style AMANDA JENNINGS considers Wayne Eagling's new wartime ballet for New English Ballet Theatre 6 ENTRE NOUS Front cover: Birmingham Royal 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS Ballet - Mathias Dingman and Delia 52 The Hamlet Complex Mathews in Juanjo Arqués' Ignite GERARD DAVIS unravels Alan Lucien Øyen's 97 WHAT’S ON latest piece for the Norwegian National Ballet 106 PEOPLE PAGE >>> Photo:ChristinLosta | heinz-bosl-stiftung.de | bayerischesjuniorballett.de Photo:ChristinLosta | heinz-bosl-stiftung.de Dance Europe - November 2018 3 ROYAL SWEDISH BALLET DANCE EUROPE Performances FOUNDED IN 1995 P.O. -

2. Ipostases of the Choreographic Dialogue 1

DOI: 10.2478/RAE-2019-0018 Review of Artistic Education no. 17 2019 171-182 2. IPOSTASES OF THE CHOREOGRAPHIC DIALOGUE 153 Cristina Todi Abstract: The analysis of the aesthetic face of dance brings to our forefront the fascination for the movement on many artists who experienced the movement and, above all, explored the possibilities of kinetic art or movement movement. In its most elevated form, dance contains not only this element but also the infinite richness of human personality. It is the perfect synthesis of the abstract and the human, of mind and intellect with emotion, discipline with spontaneity, spirituality with erotic attraction to which dance aspires; and in dance as a form of communication, it is the most vivid presentation of this fusion act that is the ideal show. Key words: Arts, ballet, dance, dialogue, aesthetic 1. Introduction The Evolution of the Syncretic Dialogue between Choreography, Theatre, Music, Literature and Visual Arts We shall initiate an approach of the discourse regarding the historical evolution of choregraphic dialogue, even from the age when this artistic genre started to assume clear contours, rather from the 17th century. Without excluding the importance of the previous periods in history, the 17th and the 18th centuries are considered to be the starting points of dance for amusement. This was often dedicated to ceremonies or entertainment. In approaching these moments, the increased attention towards the aesthetic expression and the manner in which beauty was intensified, sometimes even at the expense of the real, is notable. Moreover, the technicality under which theatrical ballet was formulated in its demonstrative forms, full of technical charge, although arid in ideas or expression that reach the sensitive cords of the viewer. -

Download Download

R evi of International American Studies ew ONE WORLD The Americas Everywhere guest-edited by Gabriela Vargas-Cetina and Manpreet Kaur Kang ISSN 1991–2773 RIAS Vol. 13, Fall–Winter № 2/2020 Review of International American Studies Revue d’Études Américaines Internationales RIAS Vol. 13, Fall—Winter № 2/2020 ISSN 1991—2773 ONE WORLD The Americas Everywhere guest-edited by Gabriela Vargas-Cetina and Manpreet Kaur Kang EDITORS Editor-in-Chief: Giorgio Mariani Managing Editor: Paweł Jędrzejko Associate Editors: Nathaniel R. Racine, Lucie Kýrová, Justin Michael Battin Book Review Editor: Manlio Della Marca Senior Copyeditor: Mark Olival-Bartley Issue Editor: Nathaniel R. Racine ISSN 1991—2773 TYPOGRAPHIC DESIGN: Hanna Traczyk / M-Studio s. c. PUBLICATION REALIZED BY: S UNIVERSITYOF SILESIA PRESS IN KATOWICE University of Silesia Press in Katowice ul. Bankowa 12b 40—007 Katowice Poland EDITORIAL BOARD Marta Ancarani, Rogers Asempasah, Antonio Barrenechea, Claudia Ioana Doroholschi, Martin Halliwell, Patrick Imbert, Manju Jaidka, Djelal Kadir, Eui Young Kim, Rui Kohiyana, Kryštof Kozák, Elizabeth A. Kuebler-Wolf, Márcio Prado, Regina Schober, Lea Williams, Yanyu Zeng. ABOUT RIAS Review of International American Studies (RIAS) is the double-blind peer- reviewed, electronic / print-on-demand journal of the International American Studies Association, a worldwide, independent, non-governmental asso- ciation of American Studies. RIAS serves as agora for the global network of international scholars, teachers, and students of America as a hemispheric and global phenomenon. RIAS is published by IASA twice a year (Fall—Winter REVUE D’ÉTUDES AMÉRICAINES INTERNATIONALE and Spring—Summer). RIAS is available in the Open Access Gold formula and is financed from the Association’s annual dues as specified in the “Membership” section of the Association’s website. -

Diaghilev and London

Diaghilev and London, A Talk by Graham Bennett, Crouch End and District U3A member We are not exactly the best of friends with Russia these days - But just over a century ago, Russia exported something that actually transformed the cultural life of London. This talk is about a quite extraordinary Russian Impresario and two equally extraordinary women who were part of his project The project was a Russian Dance Company that created a revolution in the world of dance, and London was to play a big part in its success. This company is the Ballet Russes. The impresario is Serge Diaghilev, born in 1872 in Perm in deepest Russia, who would create the Ballet Russes. Lydia Lopokova from St Petersburg, born in 1892, one of Diaghilev's star ballerinas. And last but not least, our very own Hilda Munnings from Wanstead in East London, born in 1896. Also to become a vitally important member of the company The story starts in St Petersburg in 1901, the heart of the Russian Empire, at the famous Mariinsky Theatre. Their choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Tchaikovsky had already created masterpieces such as The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. These are such familiar names to us today but they were virtually unknown outside Russia at that time. Over in England we were still having a jolly knees up and sing-along at the Music Hall and even in France, ballet had degenerated to a pale shadow of its former glory. In 1901, Lydia Lopokova, just 9 years old, auditioned for a place at the prestigious Imperial Theatre School in St Petersburg.