Ballets Russes Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season Brochure

Thirtieth Anniversary Season Pontecorvo ballet studios Barbara Pontecorvo Director Classes Start August 23, 2021! This is Where It Begins Our Covid-19 Plan Welcome back to Pontecorvo Ballet Studios for the 21-22 Season! We continue to follow all local, state and federal rules to keep your dancer and our staff safe. Happily, all teens and adults can easily get vaccinated now, and we hope you do. Vaccines are not available for our many sttudents under 12, so to keep them safe masks continue to be required in the building unless (1) you are in a studio where all dancers are 12 or older AND (2) you are fully vaccinated. Masks are still required for all in the lobby, restrooms and dressing areas regardless of vaccination status,and in the stu- dios for any dancer not vaccinated. In addition, we will continue our regimen of increased venti- lation and extra cleaning of touch services. We implemented mask requirements and other steps when we reopened in June 2020 and are happy to say that, as of July 2021, there has been, to our knowledge, NO in-studio transmis- sion of COVID-19 disease. We are so proud of our dancers and how they adapted,following all guidelines and keeping everyone safe and healthy. We urge everyone to get vaccinated as soon as they can. This is Where It Begins... - a chance to try -an opportunity to be your best -a life-long love of music -everlasting friendships -an understanding of your human body -toned muscles and good posture Pontecorvo Ballet Studios - enjoyment of regular exercise 20 Commercial Way -a well-rounded education Springboro OH 45066 -a love of performing -the end of stage fright For more information call -a career in ballet -the dream. -

Nutcracker December 1–4, 2016

ASHLEY WHEATER ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PREVIEW PERFORMANCES CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON’S NUTCRACKER DECEMBER 1–4, 2016 OPENING SEASON 2016/2017 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ASHLEY WHEATER ARTISTIC DIRECTOR GREG CAMERON EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ROBERT JOFFREY FOUNDER GERALD ARPINO FOUNDER ARTISTS OF THE COMPANY MATTHEW ADAMCZYK DERRICK AGNOLETTI YOSHIHISA ARAI AMANDA ASSUCENA ARTUR BABAJANYAN EDSON BARBOSA MIGUEL ANGEL BLANCO ANAIS BUENO FABRICE CALMELS RAÚL CASASOLA VALERIIA CHAYKINA NICOLE CIAPPONI LUCIA CONNOLLY APRIL DALY FERNANDO DUARTE CARA MARIE GARY STEFAN GONCALVEZ LUIS EDUARDO GONZALEZ DYLAN GUTIERREZ RORY HOHENSTEIN ANASTACIA HOLDEN DARA HOLMES RILEY HORTON VICTORIA JAIANI HANSOL JEONG GAYEON JUNG YUMI KANAZAWA BROOKE LINFORD GRAHAM MAVERICK JERALDINE MENDOZA JACQUELINE MOSCICKE AARON RENTERIA CHRISTINE ROCAS PAULO RODRIGUES CHLOÉ SHERMAN TEMUR SULUASHVILI OLIVIA TANG-MIFSUD ALONSO TEPETZI ELIVELTON TOMAZI ALBERTO VELAZQUEZ MAHALLIA WARD JOANNA WOZNIAK JOAN SEBASTIÁN ZAMORA SCOTT SPECK MUSIC DIRECTOR GERARD CHARLES DIRECTOR OF ARTISTIC OPERATIONS NICOLAS BLANC BALLET MASTER/PRINCIPAL COACH ADAM BLYDE SUZANNE LOPEZ BALLET MASTERS PAUL JAMES LEWIS SENIOR PIANIST/MUSIC ADMINISTRATOR GRACE KIM MATTHEW LONG COMPANY PIANISTS Patrons are requested to turn off pagers, cellular phones, and signal watches during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording devices are not allowed. Artists subject to change. 3 4 HANCHER 2016/2017 SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC HANCHER SPONSORS OF THE NUTCRACKER SUE STRAUSS RICHARD -

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

PRESS RELEASE Ballet

PRESS RELEASE Filip Barankiewicz The Artistic Director of The Czech National Ballet ballet ON-LINE WORLD PREMIERE OF THE CZECH NATIONAL BALLET CNB YOUTUBE CHANNEL PUPPET DOS SOLES SOLOS Two choreographies / double experience During 2020/2021 season The Czech National Ballet manages to stimualate creative energy and seeking new artistic impulses. The world online premiere of works by choreographers Douglas Lee and Alejandro Cerrudo ranks among them. We value every moment when we can freely create and thus contribute to the formation of a sensitive and supportive environment… Douglas Lee and Alejandro Cerrudo worked with The Czech National Ballet since August 2020. The dancers learned to exercise in face masks, disinfect their hands, split into small closed groups, take tests, protect themselves and others, watch their health and act as an evidence that the covid era shall not destroy the arts, the live theatre. In November 2020 these artists completed their new choreographies and the works were recorded. All choreographies are part of the Phoenix production which has entered the repertory of The Czech National Ballet (the third part of the premiere is Prelude und Liebestod by Cayetano Soto). We are ready to perform all three creations whenever audiences can return to our historical building. The live premiere is still to come and we hope to reconnect soon. On March 18, 2021 at 7pm we will be showing PUPPET (choreography by Douglas Lee) and on March 25, 2021 at 7pm DOS SOLES SOLOS (choreography by Alejandro Cerrudo); both works on YouTube channel of the Czech National Ballet. Douglas Lee: ‘My ballet is called Puppet. -

Vision / Dance Innovations

2020 FEBRUARY PROGRAMS 02 /03 CLASSICAL (RE)VISION / DANCE INNOVATIONS The people you trust, trust City National. Top Ranked in Client Referrals* “City National helps keep my financial life in tune.” Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor, Educator and Composer Find your way up.SM Visit cnb.com *Based on interviews conducted by Greenwich Associates in 2017 with more than 30,000 executives at businesses across the country with sales of $1 million to $500 million. City National Bank results are compared to leading competitors on the following question: How likely are you to recommend (bank) to a friend or colleague? City National Bank Member FDIC. City National Bank is a subsidiary of Royal Bank of Canada. ©2018 City National Bank. All Rights Reserved. cnb.com 7275.26 PROGRAM 02 | CLASSICAL (RE)VISION PROGRAM 03 | DANCE INNOVATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 Greetings from the Artistic Director & Principal Choreographer 05 06 Board of Trustees Endowment Foundation Board 07 SF Ballet Leadership 08 Season News 10 Off Stage 13 Pointe and Counterpoint: The Story of Programs 02 and 03 14 PROGRAM 02 Classical (Re)Vision Bespoke Director's Choice Sandpaper Ballet 22 PROGRAM 03 Dance Innovations The Infinite Ocean The Big Hunger World Premiere Etudes 30 Artists of the Company 14 39 SF Ballet Orchestra 40 SF Ballet Staff 42 Donor Events and News 46 SF Ballet Donors 61 Thank You to Our Volunteers 63 For Your Information 64 Designing Sandpaper Ballet FOLLOW US BEFORE AND AFTER THE PERFORMANCE! San Francisco Ballet SFBallet youtube.com/sfballet SFBallet 42 San Francisco Ballet | Program Book | Vol. -

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni Citation Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni. (2021). Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 04:39:03 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660266 ADAPTING PIANO MUSIC FOR BALLET: TCHAIKOVSKY’S CHILDREN’S ALBUM, OP. 39 by Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou ____________________________________ Copyright © Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou 2021 A DMA Critical Essay Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Creative Project and Lecture-Recital Committee, we certify that we have read the Critical Essay prepared by: titled: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ submission of the final copies of the essay to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this Critical Essay prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement. -

Choreography for the Camera AB

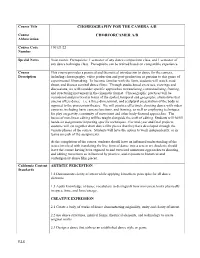

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Press Kit for Ballets Russes, Presented by Capri Releasing

PRESENTS BALLETS RUSSES A film by Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine. A fifty-year journey through the lives of the revolutionary artists who transformed dance. Running Time: 120 Minutes Media Contact: Anna Maria Muccilli AM Public Relations 1200 Bay St., Suite 900 Toronto, Ontario, M5R 2A5 416.969.9930 x 231 [email protected] For photography, please visit: http://www.caprifilms.com/capri_pressmaterial.html Geller/Goldfine P R O D U C T I O N S Ballets Russes Synopsis Ego, politics, war, money, fame, glamour, love, betrayal, grace… and dance. Ballets Russes is a feature-length documentary covering more than fifty years in the lives of a group of revolutionary artists. It tells the story of the extraordinary blend of Russian, American, European and Latin American dancers who, in collaboration with the greatest choreographers, composers and designers of the first half of the 20th century, transformed ballet from mere music hall divertissement to a true art form. From 1909, when Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev premiered his legendary Ballet Russe company in Paris, to 1962 when Serge Denham’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo performed for the last time in Brooklyn, Ballets Russes companies brought their popular, groundbreaking and often controversial choreographies to big cities and small towns around the world. Along the way, these artistic visionaries left their mark on virtually every other area of art and culture – from stage design, painting and music to Hollywood and Broadway. Through their inclusive cosmopolitanism, they also put the first African-American and Native American ballerinas on the stage. Using intimate interviews with surviving members of the Ballets Russes companies (now in their 70s, 80s and 90s) as well as rare archival materials and motion picture footage, Ballets Russes is both an ensemble character film and an historical portrait of the birth of an art form. -

Nicolle Greenhood Major Paper FINAL.Pdf (4.901Mb)

DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Major paper submitted to the faculty of Goucher College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration 2016 Abstract Title of Thesis: DIVERSITY EN POINTE: MINIMIZING DISCRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES TO INCREASE BALLET’S CULTURAL RELEVANCE IN AMERICA Degree Candidate: Nicolle Mitchell Greenhood Degree and Year: Master of Arts in Arts Administration, 2016 Major Paper Directed by: Michael Crowley, M.A. Welsh Center for Graduate and Professional Studies Goucher College Ballet was established as a performing art form in fifteenth century French and Italian courts. Current American ballet stems from the vision of choreographer George Balanchine, who set ballet standards through his educational institution, School of American Ballet, and dance company, New York City Ballet. These organizations are currently the largest-budget performing company and training facility in the United States, and, along with other major US ballet companies, have adopted Balanchine’s preference for ultra thin, light skinned, young, heteronormative dancers. Due to their financial stability and power, these dance companies set the standard for ballet in America, making it difficult for dancers who do not fit these narrow characteristics to succeed and thrive in the field. The ballet field must adapt to an increasingly diverse society while upholding artistic integrity to the art form’s values. Those who live in America make up a heterogeneous community with a blend of worldwide cultures, but ballet has been slow to focus on diversity in company rosters. -

The Exemplary Daughterhood of Irina Nijinska

ven before her birth in 1913, Irina Nijinska w.as Choreographer making history. Her uncle, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska in Revival: E was choreographing Le Sacre du Printemps, with her mother, Bronislava Nijinska, as the Chosen Maiden. But Irina was on the way, and Bronislava had The Exemplary to withdraw. If Sacre lost a great performance, Bronis lava gained an heir. Thanks to Irina, Nijinska's long neglected career has finally received the critical and Daughterhood public recognition it deserves. From the start Irina was that ballet anomaly-a of Irina Nijinska chosen daughter. Under her mother's tutelage, she did her first plies. At six, she stayed up late for lectures at the Ecole de Mouv.ement, Nijinska's revolutionary stu by Lynn Garafola dio in Kiev. In Paris, where the family settled in the 1920s, Irina studied with her mother's student Eugene Lipitzki, graduating at fifteen to her mother's own cla~s The DTH revival of , for the Ida Rubinstein company, where she also sat in Rondo Capriccioso, Nijinska's on rehearsals. Irina made her professional debut in London in last ballet, is ·her daugther 1930. The company was headed by Olga Spessivtzeva, Irina's latest project. and Irina danced under the name Istomina, the bal lerina beloved by Pushkin. That year, too, she toured with the Opera Russe a Paris, one of many ensembles · associated with her mother in which she performed. These included the Rubinstein company, as well as Theatre de la Danse Nijinska, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and the Polish Ballet.