Read the Full Volume Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

Performing Disability. Dance. Artistry

Performing Disability. Dance. Artistry. PAGE 2 ACCESSIBILITY This document has been designed with a number of features to optimize accessibility for low-vision scenarios and electronic screen readers: √ Digital Version: Alt text metadata has been added to describe all charts and images. √ Digital Version: Alt text has also been duplicated as actual text captions for screen readers that do not read metadata and instead read what is visually seen on the screen. (Note: This will result in redundancy for those using advanced screen readers, which read both.) √ Digital Version: The layout has been designed continuously and free of complex layouts in order to maintain a simple and consistent body flow for screen readers. √ Digital Version: Page numbers are tagged to be ignored by screen readers so as to not interrupt information flow (and at the top of the page for other screen readers). √ Headlines and body introductions are set at 18 points, which is considered large print by the American Printing House for the Blind (APH). √ Body text is set at 14 points, which is considered enlarged by the APH. √ Fine print and labels are set in heavier weights to increase readability. √ High contrast has been maintained by using black body text. √ Ample white space has been applied (to page margins and line spacing) to make pages more readable by providing contrast to the print and creating luminance around the text. PAGE 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Acknowledgments 6 Testimony 8 Introduction 11 Methodology 19 Key Learning 28 Recommendations 49 Appendices Profiles Conversation Series Videos & Field Notes by moderator Kevin Gotkin Application & Reporting Templates Interview Transcripts Cover: Cover: Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson, Kinetic Light. -

Arts and Special Education Exemplary Programs and Approaches Introduction

2013 VSA Intersections: Arts and Special Education A Jean Kennedy Smith Arts and Disability Program Exemplary Programs and Approaches Acknowledgments and Credits The John F. Kennedy Center Authors for the Performing Arts Sally Bailey, MFA David M. Rubenstein Chairman Jean B. Crockett, PhD Michael M. Kaiser Rhonda Vieth Fuelberth, PhD President Kim Gavin, MA Darrell M. Ayers Beverly Levett Gerber, EdD Vice President, Education and Jazz Donalyn Heise, EdD Betty R. Siegel Director, VSA and Accessibility Veronica Hicks, MA Lynne Horoschak, MA Editor Sophie Lucido Johnson Sharon M. Malley, EdD Karen T. Keifer-Boyd, PhD Editorial reviewers L. Michelle Kraft, PhD Beverly Levett Gerber, EdD Linda Krakaur, MSt Karen T. Keifer-Boyd, PhD Lynda Ewell Laird, MM Laurie MacGillivray, PhD Alice Hammel, PhD Tim McCarty, MA Barbara Pape, EdM Mark Tomasic, MFA You are welcome to copy and distribute this publication with the following credit: Produced by The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, © 2014. The content of this publication, developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not as- sume endorsement by the federal government. Contents Introduction 5 Sharon M. Malley, Editor Next Steps: New Research and Teaching Journals 10 at the Intersection of the Arts and Special Education Beverly Levett Gerber, Karen T. Keifer-Boyd, and Jean B. Crockett Exemplary Theatre Practices: Creating Barrier-Free Theatre 25 Sally Bailey Visual Theatre: Building -

Spotlight on Erie – 19 Flagship Multimedia, Inc, 1001 State St., Julian Is Referring to Voodoo Able, with Window Air Condition- Suite 901, Erie, Pa, 16501

CONTENTS: From the Editors The only local voice for Gainfully employing Erie’s strengths news, arts, and culture. September 28, 2016 Editors-in-Chief: live on the lower west This circumstance, as we all Brian Graham & Adam Welsh side of Erie, and I like my know, has a paralyzing ripple Managing Editor: Just a Thought – 4 Katie Chriest “I neighborhood a lot.” effect. Assignment Editor: Taking a cue from autumn That’s how Dan Schank be- “When the health of our Nick Warren gins his feature on concentrated schools relies on the value of Contributing Editors: poverty in this issue. Schank’s our properties, we incentivize Ben Speggen opening immediately under- flight and punish those who Jim Wertz A Day in the Life of an Erie City mines the generalization that stay put,” Schank writes. “When Contributors: Lisa Austin, Civitas Firefighter – 7 young professionals don’t want trust breaks down between our Ed Bernik to live here. The reality, as usu- police and our most vulnerable Mary Birdsong Running into a blazing building al, is far more nuanced than the neighborhoods, crime flourish- Tracy Geibel Lisa Gensheimer can be ‘terrifying,’ but some supposition. es and abuses occur. When fear Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp As Schank explains, “the prob- of that crime escalates, foot traf- Dan Schank choose to do it, anyway. Tommy Shannon lem isn’t that I wouldn’t be fic disappears, businesses fail, Ryan Smith happy in Frontier or Fairview. and basic needs can’t be met.” Ti Sumner Matt Swanseger The problem is that I’m already Schank’s approach is multifac- Bryan Toy happy where I am. -

Ready2go Arts In-Person 2020-2021

CLEVELAND EDUCATION RTCONSORTIUM IN RESIDENCE AT SCLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY Ready To Go Arts Programs In-person and On-site 2020-2021 As the coronavirus has forced Cleveland Arts Education Consortium members to move arts learning online, we invite you to browse this list of in-person programs and activities for future options. In the meanwhile, check our Spring 2021 ONLINE book for new arts adventures for every age. Questions? Call or email the person listed with the program or Judith Ryder, CAEC Manager 216-802-3378. [email protected] Ready to Go Arts Programs 2020-2021 In these pages you’ll find a range of in-person arts programs for all ages from the Cleveland Arts Education Consortium member organizations listed below. Follow the numbers to find programs. While a few members are safely presenting some of their in-person programs, we suggest you check our ONLINE Spring 2021 book for the greatest range of options. Organization # and Name # of Programs included Arts Discipline 1 - Apollo’s Fire 2 programs MUSIC 2 - Art House, Inc. 2 programs VISUAL ART 3 - Beck Center for the Arts 2 Programs MULTIPLE ARTS 4 - Bluewater Chamber Orchestra 3 Programs MUSIC 5 - Boys and Girls Clubs of Cleveland/Open Tone Music 1 Programs MUSIC 6 - Broadway School of Music & the Arts 3 Programs MUSIC 7 - Center for Arts-Inspired Learning 3 Programs MULTIPLE ARTS 8 - Chris Siebert via CAL 1 Program THEATER/CREATIVE WRITING 9 - City Music Cleveland 2 Programs MUSIC & OTHER ARTS 10 - Cleveland Association of Black Storytellers, Inc. 2 Programs STORYTELLING/CULTURE -

2017-Festival-Brochure

www.ohiodance.org 2 www.ohiodance.org Dance Matters: Inscribing The OhioDance Festival and Conference is an annual statewide celebration of dance through classes, workshops, discussions and performances. Nationally recognized Alexis Willson, will serve as a guest artist. As a professional dancer she has performed classically and commercially all over the world. Alexis earned her B.F.A. in drama from the prestigious Carnegie-Mellon University. After retiring from dancing, she acted in com- mercials and later became a casting associate. Alexis has written and published poetry, a full length musical, made contributions to a variety of published works, and self-published her recent memoir, Not So Black and White. Friday, April 28 Young Artists’ Concert, 10:30-11:30am Master classes begin at 2:30pm. 8:00pm: BalletMet’s Romeo and Juliet at the Ohio Theatre 7:00pm Reception Saturday, April 29 Full day of master classes 12:30-1:30pm Alexis Wilson guest speaker after the Luncheon 2-3:30pm Virtual Dance Collection unveiling Panel Discussion 3:45 Alexis Wilson Composition Master Class 6:30pm Evening Performance and Award Ceremony. Awards will be presented to Dr. Melanye White Dixon for outstanding contributions to the advancement of dance education, Sheri Williams for outstanding contributions to the advancement of the dance artform and Pamela Young for outstanding contributions to the advancement of dance arts administration. The Maggie Patton dance scholarship and OhioDance outstanding dance student will be awarded to a graduating high school student. Sunday, April 30, 10:00am-3:00pm- Wellness day and Master classes Registration and Classes Festival Guide Index held at BalletMet Columbus Festival Schedule........................pg. -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•... -

Fiscal Year 2017 Appropriations Request

National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations Request For Fiscal Year 2017 Submitted to the Congress February 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations Request for Fiscal Year 2017 Submitted to the Congress February 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Overview ......................................................................... 1 II. Creation of Art .............................................................. 21 III. Engaging the Public with Art ........................................ 33 IV. Promoting Public Knowledge and Understanding ........ 83 V. Program Support ......................................................... 107 VI. Salaries and Expenses ................................................. 115 www.arts.gov BLANK PAGE National Endowment for the Arts – Appropriations Request for FY 2017 OVERVIEW The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is America’s chief funder and supporter of the arts. As an independent Federal agency, the NEA celebrates the arts as a national priority, critical to America’s future. More than anything, the arts provide a space for us to create and express. Through grants given to thousands of non-profits each year, the NEA helps people in communities across America experience the arts and exercise their creativity. From visual arts to digital arts, opera to jazz, film to literature, theater to dance, to folk and traditional arts, healing arts to arts education, the NEA supports a broad range of America’s artistic expression. Throughout the last 50 years, the NEA has made a significant contribution to art and culture in America. The NEA has made over 147,000 grants totaling more than $5 billion dollars, leveraging up to ten times that amount through private philanthropies and local municipalities. The NEA further extends its work through partnerships with state arts agencies, regional arts organizations, local leaders, and other Federal agencies, reaching rural, suburban, and metropolitan areas in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, special jurisdictions, and military installations. -

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

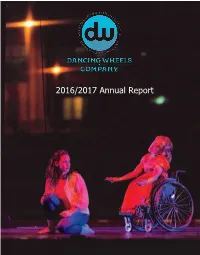

2016/2017 Annual Report

2016/2017 Annual Report STAFF MEMBERS Mary Verdi-Fletcher, President/Founding Artistic Director Dana Kuhn, Manager of Development and Communications Kallie Beck, Manager of Marketing and Operations Catherine Meredith, Rehearsal Director Jessica Hodges, Manager of Education and Outreach Emma Parker, School Coordinator Sara Lawrence-Sucato, Tour Manager Matt Bowman, Social Media Manager Singer, Berger, Press & Co., Accountant COMPANY MEMBERS Matt Bowman, McKenzie Beaverson, Kelly Clymer, Tanya Ewell, Rilley Jacob, Kevin D. Marr II, Emily Schwarting, Demarco Sleeper, Sara Lawrence-Sucato, Mary Verdi-Fletcher, Ja’Vaughn White, Lianne Zydowicz BOARD MEMBERS Suzanne M. Joseph, Chair Karen Lazar Thomas P. Gilligan, Vice-Chair David S. Lockman Stephen H. Spaeth, Treasurer Bob Marx Wendy Campbell, Secretary Catherine McCain Kerry M. Agins, Esq. Janice McCullough Ridgeway Francois Bethoux, MD Kathleen J. Pantano, PT, Ph.D Donna L. Flynt Brian Pritchard William Dorsky Mary Verdi-Fletcher Stacy Gay President/Founding Artistic Director Maria Jukic John Voso, Jr. Brian J. Jungeberg John Wright Kevin Kuhn THE ORGANIZATION THE ORGANIZATION Advisory Council: Michael Belkin, Kevin Rhodes, Mickie McGraw ATR-BC Emeritus: Rabbi Michael A. Oppenheimer TEACHERS FROM THE SCHOOL OF DANCING WHEELS Mary Verdi-Fletcher, Emma Parker, Kelly Clymer, Brittany Kaplan, Gabriella Martinez, Sara Lawrence-Sucato, Catherine Meredith, Demarco Sleeper, Shannon Sterne, Lianne Zydowicz. Dear Friends, This season marked the 36th year of the Dancing Wheels Com- pany and School, -

The Lived Experience of University Students with Visual Impairments and Their Sighted Partners’ Participation in Inclusive Social Ballroom Dance

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS AND THEIR SIGHTED PARTNERS’ PARTICIPATION IN INCLUSIVE SOCIAL BALLROOM DANCE. Faine Bisset Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Psychology) at Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Dr J R Bantjes Co-supervisor: Prof E S Bressan March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: ................................................ Date: ................................................ Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Ballroom and Latin American dance appear to be gaining popularity among people with disabilities, as a form of exercise and leisure activity. However, the majority of research conducted in this field seems to have focused on the physicality of dancers’ movements, while overlooking their unique interpretations of such an experience. Furthermore, there appears to be a dearth of literature on the experience of dance for visually impaired individuals. The aim of this study was to give a voice to the lived experience of visually impaired dancers and their sighted partners who participate in inclusive social ballroom and Latin American dance. The participants were members of the Differently-abled Dance Class that was held by the dance society of a university situated in the Western Cape, South Africa. This qualitative study was conducted within the theoretical framework of the social theory of disability. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries.