Helpmann, Sir Robert (1909-1986) by John Mcfarland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

www.fusion-journal.com Fusion Journal is an international, online scholarly journal for the communication, creative industries and media arts disciplines. Co-founded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University (Australia) and the College of Arts, University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), Fusion Journal publishes refereed articles, creative works and other practice-led forms of output. Issue 17 AusAct: The Australian Actor Training Conference 2019 Editors Robert Lewis (Charles Sturt University) Dominique Sweeney (Charles Sturt University) Soseh Yekanians (Charles Sturt University) Contents Editorial: AusAct 2019 – Being Relevant .......................................................................... 1 Robert Lewis, Dominique Sweeney and Soseh Yekanians Vulnerability in a crisis: Pedagogy, critical reflection and positionality in actor training ................................................................................................................ 6 Jessica Hartley Brisbane Junior Theatre’s Abridged Method Acting System ......................................... 20 Jack Bradford Haunted by irrelevance? ................................................................................................. 39 Kim Durban Encouraging actors to see themselves as agents of change: The role of dramaturgs, critics, commentators, academics and activists in actor training in Australia .............. 49 Bree Hadley and Kathryn Kelly ISSN 2201-7208 | Published under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) From ‘methods’ to ‘approaches’: -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Publications

Michelle Potter: Publications Michelle Potter: Publications Books and articles (peer reviewed works are marked with an asterisk *) ‘Robert Helpmann: Behind the scenes with the Australian Ballet, 1963–1965.’ Dance Research (Edinburgh), 34:1 (Summer 2016), forthcoming* ‘Elektra: Helpmann uninhibited.’ In Richard Cave and Anna Meadmore (eds),The many faces of Robert Helpmann (Alton: Dance Books, 2016), forthcoming Dame Maggie Scott: A Life in Dance (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2014), 368 pp, colour and b & w illustrations, ISBN 9781922182388 (also published as a e-book ISBN 9781925095364) Meryl Tankard: an original voice (Canberra: Dance writing and research, 2012), 210 pp, unillustrated, ISBN 9780646591445 ‘Merce Cunningham’, ‘Rudolf Nureyev’. America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures (Washington, DC: Dance Heritage Coalition, 2012)* http://www.danceheritage.org/cunningham.html; http://www.danceheritage.org/nureyev.html ‘The Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet 1934–1935: Australia and beyond.’ Dance Research (Edinburgh), 29:1 (Summer 2011), pp. 61–96* ‘People, patronage and promotion: the Ballets Russes tours to Australia, 1936–1940.’ Ballets Russes: the art of costume (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2010), pp. 182–193* ‘Tributes: Impressions—Irina Baronova; The fire and the rose—Valrene Tweedie.’ Brolga (Canberra), 29 (December 2008), pp. 6–16 ‘Archive bündeln: Das Beispiel Australien.’ trans. Franz Anton Cramer. Tanz und ArchivePerspectiven für ein kulturelles Erbe, ed. Madeline Ritter, series Jahresmitteilungen von Tanzplan Deutschland (Berlin: Tanzplan Deutschland, 2008), pp. 50–53* ‘Arnold Haskell in Australia: did connoisseurship or politics determine his role?’ Dance Research (Edinburgh), 24:1(Summer 2006), pp. 37–53* ‘Chapter 7: In the air: extracts from an interview with Chrissie Parrott.’ Thinking in Four Dimensions: Creativity and Cognition in Contemporary Dance, eds. -

Remembering Edouard Borovansky and His Company 1939–1959

REMEMBERING EDOUARD BOROVANSKY AND HIS COMPANY 1939–1959 Marie Ada Couper Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne 1 ABSTRACT This project sets out to establish that Edouard Borovansky, an ex-Ballets Russes danseur/ teacher/choreographer/producer, was ‘the father of Australian ballet’. With the backing of J. C. Williamson’s Theatres Limited, he created and maintained a professional ballet company which performed in commercial theatre for almost twenty years. This was a business arrangement, and he received no revenue from either government or private sources. The longevity of the Borovansky Australian Ballet company, under the direction of one person, was a remarkable achievement that has never been officially recognised. The principal intention of this undertaking is to define Borovansky’s proper place in the theatrical history of Australia. Although technically not the first Australian professional ballet company, the Borovansky Australian Ballet outlasted all its rivals until its transformation into the Australian Ballet in the early 1960s, with Borovansky remaining the sole person in charge until his death in 1959. In Australian theatre the 1930s was dominated by variety shows and musical comedies, which had replaced the pantomimes of the 19th century although the annual Christmas pantomime remained on the calendar for many years. Cinemas (referred to as ‘picture theatres’) had all but replaced live theatre as mass entertainment. The extremely rare event of a ballet performance was considered an exotic art reserved for the upper classes. ‘Culture’ was a word dismissed by many Australians as undefinable and generally unattainable because of our colonial heritage, which had long been the focus of English attitudes. -

Media Kit the Australian Ballet 2016 Media Kit

MEDIA KIT THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2016 MEDIA KIT MEDIA RELEASE Symphony in C is a parade of bite-size classical and contemporary 2016 Season Packages are available from 9am Thursday 24 The Australian Ballet announces ballet delights. The mixed bill begins with the black and white September in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. an explosive new season, blending symmetry of a George Balanchine extravaganza. The gala line- up to follow is a suite of perfect ballet moments to show the art NOTES TO EDITORS timeless classics and contemporary form at its radiant best. Highlights include the world premiere of two new works by emerging choreographers and rising stars Founded in 1962, The Australian Ballet is one of the world’s leading of The Australian Ballet, Alice Topp and Richard House. This ballet companies delivering extraordinary performances for over works, including the Australian 50 years. A commitment to artistic excellence, a spirited style work is exclusive to Sydney and opens in April, as the classical counterpoint to Vitesse. and a willingness to take risks have defined the company from premiere of the Nijinsky masterpiece, its earliest days, both onstage and off. The company exists to the return of much-loved classics Romance moves centre stage, when Houston Ballet brings the inspire, delight and challenge audiences through the power and world’s most famous love story, Romeo and Juliet, to Melbourne. quality of its performances. Coppélia, Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, Artistic Director Stanton Welch, concurrently a Resident Choreographer with The Australian Ballet, is a master of story In addition to 70 acclaimed dancers, The Australian Ballet and world premiere works by rising and spectacle. -

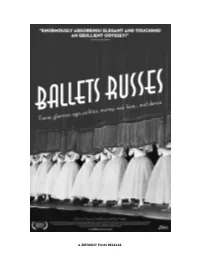

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

And We Danced Episode 3 Credits

AND WE DANCED WildBear Entertainment, ABC TV and The Australian Ballet acknowledge the Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present. EPISODE THREE Executive Producers Veronica Fury Alan Erson Michael Tear Development Producer Stephen Waller INTERVIEWEES Margot Anderson Dimity Azoury Peter F Bahen Lisa Bolte Adam Bull Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chengwu Guo David Hallberg Ella Havelka Steven Heathcote AM Marilyn Jones OBE Ako Kondoo David McAllister AC Graeme Murphy AO Stephen Page AO Lisa Pavane Colin Peasley OAM Marilyn Rowe AM OBE Amber Scott Hugh Sheridan Fiona Tonkin OAM Elizabeth Toohey Emma Watkins Michael Williams SPECIAL THANKS TO David McAllister AC David Hallberg Nicolette Fraillon AM 1 Artists of The Australian Ballet past and present Artists of Bangarra Dance Theatre past and present Orchestra Victoria Opera Australia Orchestra The Australian Ballet School Tony Iffland Janine Burdeu The Wiggles The Langham Hotel Melbourne Brett Ludeman, David Ward ARCHIVE SOURCES The Australian Ballet ABC Archives National Film and Sound Archive Associated Press Getty The Apiary The Wiggles International Arts Newspix Bolshoi Ballet American Ballet Theater FOOTAGE The Australian Ballet Year of Limitless Possibilities, 2020 Brand Film Artists of The Australian Ballet Valerie Tereshchenko, Robyn Hendricks, Dimity Azoury, Callum Linnane, Jake Mangakahia Choreography David McAllister AM Cinematography Brett Ludeman and Ryan Alexander Lloyd Produced by Robyn Fincham and Brett Ludeman Filmed on location at Mundi Mundi Station, via Silverton NSW The Living Desert Sculpture Park, Junction Mine, The Imperial Fine Accommodation, Broken Hill NSW. -

Diaghilev and London

Diaghilev and London, A Talk by Graham Bennett, Crouch End and District U3A member We are not exactly the best of friends with Russia these days - But just over a century ago, Russia exported something that actually transformed the cultural life of London. This talk is about a quite extraordinary Russian Impresario and two equally extraordinary women who were part of his project The project was a Russian Dance Company that created a revolution in the world of dance, and London was to play a big part in its success. This company is the Ballet Russes. The impresario is Serge Diaghilev, born in 1872 in Perm in deepest Russia, who would create the Ballet Russes. Lydia Lopokova from St Petersburg, born in 1892, one of Diaghilev's star ballerinas. And last but not least, our very own Hilda Munnings from Wanstead in East London, born in 1896. Also to become a vitally important member of the company The story starts in St Petersburg in 1901, the heart of the Russian Empire, at the famous Mariinsky Theatre. Their choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Tchaikovsky had already created masterpieces such as The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. These are such familiar names to us today but they were virtually unknown outside Russia at that time. Over in England we were still having a jolly knees up and sing-along at the Music Hall and even in France, ballet had degenerated to a pale shadow of its former glory. In 1901, Lydia Lopokova, just 9 years old, auditioned for a place at the prestigious Imperial Theatre School in St Petersburg. -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

1 Giselle the Australian Ballet

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET GISELLE 1 Lifting them higher Telstra is supporting the next generation of rising stars through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Award. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, partners since 1984. 2018 Telstra Ballet Dancer Award Winner, Jade Wood | Photographer: Lester Jones 2 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2019 SEASON Lifting them higher Telstra is supporting the next generation of rising stars through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Award. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, partners since 1984. 1 – 18 MAY 2019 | SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE Government Lead Principal 2018 Telstra Ballet Dancer Award Winner, Jade Wood | Photographer: Lester Jones Partners Partners Partner Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Ridler Above: Ako Kondo. Photography Lynette Wills Richard House, Valerie Tereshchenko and Amber Scott. Photography Lynette Wills 4 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2019 SEASON NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Giselle has a special place in The Australian Ballet’s history, and has been a constant in our repertoire since the company’s earliest years. The superstars Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev danced it with us in 1964, in a production based on the Borovansky Ballet’s. Our founding artistic director, Peggy van Praagh, created her production in 1965; it premiered in Birmingham on the company’s first international tour, and won a Grand Prix for the best production staged in Paris that year. It went on to become one of the most frequently performed ballets in our repertoire. Peggy’s production came to a tragic end when the scenery was consumed by fire on our 1985 regional tour. The artistic director at the time, Maina Gielgud, created her own production a year later. -

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Markova, Alicia #1064 6/30/95 Preliminary Listing Box 1 I. Correspondence. [F. 1] A. Markova, Alicia. ANS to unknown, 1 p., n.d. B. Invitation to the annual meeting of the Boston University Friends of the Libraries where AM will speak, May 8, 1995. II. Printed Material. A. Newspaper clippings. 1. AMarkova Rounding Out 33 Years on Her Toes,@ by Art Buchwald, New York Herald Tribune, Nov. 22, 1953. [F. 2] 2. AThe Ballet Theatre,@ by Walter Terry, New York Herald Tribune, Apr. 16, 1955. 3. Printed photo of AM, Waterbury American, Nov. 25, 1957. 4. ATotal Role Recall,@ by Jann Parry, The Observer Review, Jan. 29, 1995. 5. AThe Nightingale Dances Again,@ by Ismene Brown, The Daily Telegraph, Feb. 3, 1995. 6. AA Step in Time,@ by David Dougill, The Sunday Times, Feb. 5, 1995. 7. AFanfare for Stars With a Place in Our Hearts,@ by Michael Owen, Evening Standard, Mar. 21, 1995. B. Photocopied pages from an unidentified printed source; all images of AM; 13 p. total. C. Promotional brochure for Yorkshire Ballet Seminars, July 29 - Aug. 26, 1995. D. Booklets. [F. 3] 1. AEnglish National Ballet,@ for a ARoyal gala performance in celebration of the 80th birthday of the President and co-founder of the company, Dame Alicia Markova ...,@ Nov. 27, 1990. 2. AA Dance Spectacular, in tribute to Dame Alicia Markova DBE, on the occasion of her 80th birthday ... in aid of The Dance Teachers= Benevolent Fund,@ Dec. 2, 1990. III. Photographs.