Parliament of India Rajya Sabha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Standing Committee Report

REPORT NO. 85 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE EIGHTY-FIFTH REPORT On THE HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS AND ACQUIRED IMMUNE DEFICIENCY SYNDROME (PREVENTION AND CONTROL) BILL, 2014 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 29 th April, 2015) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 29 th April , 2015 ) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi April, 2015/ Vaisakha, 1937 (SAKA) PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE EIGHTY-FIFTH REPORT On THE HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS AND ACQUIRED IMMUNE DEFICIENCY SYNDROME (PREVENTION AND CONTROL) BILL, 2014 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 29 th April, 2015) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 29 th April , 2015 ) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi April, 2015/ Vaisakha, 1937 (SAKA) CONTENTS PAGES 1. C OMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ......................................................................................... (i)-(ii) 2. P REFACE ............................................................................................................................... (iii) *3. L IST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................ (iv) 4. R EPORT ................................................................................................................................... 1 *5. O BSERVATIONS /R ECOMMENDATIONS — AT A -

List of Winning Candidated Final for 16Th

Leading/Winning State PC No PC Name Candidate Leading/Winning Party Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam Andhra Pradesh 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen Andhra Pradesh 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 16 Mahabubabad P. Balram Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 17 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao Telugu Desam Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana Andhra Pradesh 18 Aruku Deo Vyricherla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 19 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 20 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 21 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari -

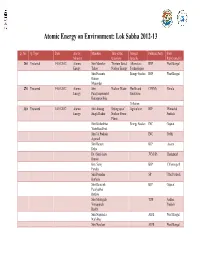

Atomic Energy on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13

Atomic Energy on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13 Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Subject Political Party State Ministry Questions Specific Representative 244 Unstarred 14.03.2012 Atomic Shri Manohar Thorium Based Alternative RSP West Bengal Energy Tirkey Nuclear Energy Technologies Shri Prasanta Energy Studies RSP West Bengal Kumar Majumdar 274 Unstarred 14.03.2012 Atomic Shri Nuclear Waste Health and CPI(M) Kerala Energy Parayamparanbil Sanitation Kuttappan Biju Pollution 310 Unstarred 14.03.2012 Atomic Shri Anurag Setting up of Agriculture BJP Himachal Energy Singh Thakur Nuclear Power Pradesh Plants Shri Kishanbhai Energy Studies INC Gujarat Vestabhai Patel Shri Jai Prakash INC Delhi Agarwal Shri Ramen BJP Assam Deka Dr. (Shri) Ajay JVM (P) Jharkhand Kumar Km. Saroj BJP Chhattisgarh Pandey Shri Premdas SP Uttar Pradesh Katheria Shri Ramsinh BJP Gujarat Patalyabhai Rathwa Shri Modugula TDP Andhra Venugopala Pradesh Reddy Shri Nripendra AIFB West Bengal Nath Roy Shri Narahari AIFB West Bengal Mahato Shri Pradeep INC Odisha Majhi Shri Om Ind. Bihar Prakash Yadav 378 Unstarred 14.03.2012 Atomic Shri Radha Uranium Alternative BJP Bihar Energy Mohan Singh Reserves Technologies Shri Hari Energy Studies BJP Bihar Manjhi Shri BJP Maharashtra Harischandra Deoram Chavan 387 Unstarred 14.03.2012 Atomic Shri Bharat Ram Kudankulam Energy Studies INC Rajasthan Energy Meghwal Nuclear Power Plant Shri Bhakta INC Odisha Charan Das Shri Arjun Ram BJP Rajasthan Meghwal Km. Saroj BJP Chhattisgarh Pandey Shri Rayapati INC Andhra Sambasiva Rao Pradesh *119 Starred 21.03.2012 Atomic Shri Ananth Effects of Health and BJP Karnataka Energy Kumar Radiation Sanitation Pollution 1181 Unstarred 21.03.2012 Atomic Smt. -

Number and Types of Constituencies

Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 3 - NUMBER AND TYPES OF CONSTITUENCIES STATE/UT Type of Constituencies Gen SC ST Total No Of Constituencies Where Election Completed Andhra Pradesh 32 7 3 42 42 Arunachal Pradesh 2 0 0 2 2 Assam 11 1 2 14 14 Bihar 34 6 0 40 40 Goa 2 0 0 2 2 Gujarat 20 2 4 26 26 Haryana 8 2 0 10 10 Himachal Pradesh 3 1 0 4 4 Jammu & Kashmir 6 0 0 6 6 Karnataka 21 5 2 28 28 Kerala 18 2 0 20 20 Madhya Pradesh 19 4 6 29 29 Maharashtra 39 5 4 48 48 Manipur 1 0 1 2 2 Meghalaya 0 0 2 2 2 Mizoram 0 0 1 1 1 Nagaland 0 0 1 1 1 Orissa 13 3 5 21 21 Punjab 9 4 0 13 13 Rajasthan 18 4 3 25 25 Sikkim 1 0 0 1 1 Tamil Nadu 32 7 0 39 39 Tripura 1 0 1 2 2 Uttar Pradesh 63 17 0 80 80 West Bengal 30 10 2 42 42 Chattisgarh 6 1 4 11 11 Jharkhand 8 1 5 14 14 Uttarakhand 4 1 0 5 5 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 1 0 0 1 1 Chandigarh 1 0 0 1 1 Dadra & Nagar Haveli 1 0 0 1 1 Daman & Diu 1 0 0 1 1 NCT OF Delhi 6 1 0 7 7 Lakshadweep 0 0 1 1 1 Puducherry 1 0 0 1 1 Total 412 84 47 543 543 1 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 4 - POLLING STATION INFORMATION Polling Stations General Electors Service Electors Grand Total State/UT PC No. -

Parliamentary Bulletin

RAJYA SABHA Parliamentary Bulletin PART-II Nos.: 51236-51237] WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2013 No. 51236 Committee Co-ordination Section Meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth As intimated by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, a meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth on the subject ‘Youth and Social Media: Challenges and Opportunities’ will be held on Thursday, 05 September, 2013 at 1530 hrs. in Committee Room No.074, Ground Floor, Parliament Library Building, New Delhi. Shri Naman Pugalia, Public Affairs Analyst, Google India will make a presentation. 2. Members are requested to kindly make it convenient to attend the meeting. ——— No. 51237 Committee Co-ordination Section Re-constitution of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees (2013-2014) The Department–related Parliamentary Standing Committees have been reconstituted w.e.f. 31st August, 2013 as follows: - Committee on Commerce RAJYA SABHA 1. Shri Birendra Prasad Baishya 2. Shri K.N. Balagopal 3. Shri P. Bhattacharya 4. Shri Shadi Lal Batra 2 5. Shri Vijay Jawaharlal Darda 6. Shri Prem Chand Gupta 7. Shri Ishwarlal Shankarlal Jain 8. Shri Shanta Kumar 9. Dr. Vijay Mallya 10. Shri Rangasayee Ramakrishna LOK SABHA 11. Shri J.P. Agarwal 12. Shri G.S. Basavaraj 13. Shri Kuldeep Bishnoi 14. Shri C.M. Chang 15. Shri Jayant Chaudhary 16. Shri K.P. Dhanapalan 17. Shri Shivaram Gouda 18. Shri Sk. Saidul Haque 19. Shri S. R. Jeyadurai 20. Shri Nalin Kumar Kateel 21. Shrimati Putul Kumari 22. Shri P. Lingam 23. Shri Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda 24. Shri Kadir Rana 25. Shri Nama Nageswara Rao 26. Shri Vishnu Dev Sai 27. -

C O N T E N T S

25.08.2011 1 C O N T E N T S Fifteenth Series, Vol.XVIII, Eighth Session, 2011/1933 (Saka) No.17, Thursday, August 25, 2011/Bhadra 3, 1933(Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S SUBMISSION BY MEMBER 4-5 Situation arising out of fast staged by Shri Anna Hazare on Lok Pal Bill ORAL ANSWER TO QUESTION *Starred Question No.321 6-10 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos.322 to 340 11-103 Unstarred Question Nos.3681 to 3910 104-492 *The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. 25.08.2011 2 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 493-495 COMMITTEE ON PRIVATE MEMBERS’ BILLS 495 AND RESOLUTIONS 20th Report COMMITTEE ON PAPERS LAID 495 ON THE TABLE 7th Report STANDING COMMITTEE ON INFORMATION 495 TECHNOLOGY 25th Report MOTION RE:TWENTY-NINTH REPORT OF 496 BUSINESS ADVISORY COMMITTEE MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 497-516 (i) Need to start work on Srinagar Hydroelectric Power Project in Uttarakhand Shri Satpal Maharaj 498 (ii) Need to expedite work on new Sabari and Edappally-Guruvayoor rail line and augment railway services in Chalakudy Parliamentary Constituency, Kerala Shri K.P. Dhanapalan 499 (iii) Need to take measures to control flood caused by river Ghagra in Barabanki Parliamentary Constituency , Uttar Pradesh and provide immediate relief to the affected people of the region Shri P.L. Punia 500 (iv) Need to release funds for payment of stipend to children under National Child Labour Project in Udaipur Parliamentary Constituency, Rajasthan Shri Raghuvir Singh Meena 501 25.08.2011 3 (v) Need to accord permission for construction of multi- level and underground parking complexes in Delhi Shri Mahabal Mishra 502 (vi) Need to expedite the completion of Gosikhurd Project in Maharashtra and to give adequate compensation to the farmers whose lands have been acquired for the project Shri Vilas Muttemwar 503-504 (vii) Need to make FM Radio Station in Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh operational Dr. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

C O N T E N T S

05.09.2011 1 C O N T E N T S Fifteenth Series, Vol.XIX, Eighth Session, 2011/1933 (Saka) No.23, Monday, September 5, 2011/ Bhadra 14, 1933(Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S REFERENCE BY THE SPEAKER 2-3 Teacher’s Day celebrated in the country in honour of former President Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos.441 4-8 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos.442 to 460 9-70 Unstarred Question Nos.5061 to 5290 71-627 05.09.2011 2 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 628-631 STATEMENT BY MINISTER Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 10th Report of Standing Committee on Coal and Steel on Demands for Grants (2009-10) pertaining to the Ministry of Steel Shri Beni Prasad Verma NATIONAL ACADEMIC DEPOSITORY BILL, 2011 633 RE: QUESTION OF CONSIDERING AND SUPPORTING 634 THE MOTION AND THE ADDRESS SUPPORTED BY THE COUNCIL OF STATES IN VIEW OF RESIGNATION BY JUSTICE SOUMITRA SEN, JUDGE OF CALCUTTA HIGH COURT Shri Salman Khursheed MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 635-656 (i) Need to improve the facilities for and appoint adequate number of doctors and medical/para medical staff in ESI Hospital at Mukkudal in Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu Shri S.S. Ramasubbu 636 (ii) Need to create awareness for eye donation among people Shri Manicka Tagore 637 (iii) Need to start work on Guruvayur to Thirunavaya rail-line project in Kerala Shri M.K. Raghavan 638 05.09.2011 3 (iv) Need to convert 51st India Reserve Batallion into Lakshadweep State Armed Force and make provision for posting/deployment of personnel of India Reserve Battalion in Union Territory to which they belong Shri Hamdullah Sayeed 639 (v) Need to run Ordnance Equipment Factory in Kanpur to its full capacity Shri Harsh Vardhan 640 (vi) Need to take suitable action to settle the cases of Bangladeshi nationals living in Assam Shri Lalit Mohan Suklabaidya 641 (vii) Need to sanction necessary funds for modernization of Buckingham Canal in Ongole Parliamentary Constituency, Andhra Pradesh as a part of National Waterways No. -

LARGEST DEMOCRACY but LOWEST VOTING We Have

EDITOR\DIRECTOR The news bits are formed on the happening of events. But analyzing the incidents happening since last one year, we don’t deserve such good news. As in past one year there are several harrowing and sorrowful Scams like CWG, Adarsh Society, 2G Spectrum and expecting many more to come have hampered the faith in our democracy and thrown the populous voters in wilderness. These are clear indication of deteriorating Indian politics and Politicians. In the event of above scams and frequent disruptions in Parliament LARGEST working and that too at the cost of hard earned citizen’s money by our own elected representatives who are competing hard among DEMOCRACY BUT themselves for making bigger scams. It is clear that they don’t feel LOWEST VOTING ashamed off but the Indian voters are ashamed of their choice of representation and repent on their franchise. If Voters feel that the We have opportunity to voting is hoax, then there is nothing wrong. change the scenario But even then the positive message in casting vote is to replace corrupt representatives by honest one to change the corrupt politicians to bring effective leaders and for this their perseverance and vigil hard efforts are seen. It is apparent that the current civil movement by civil society has brought the whole nation under one umbrella, which is an indication for replacement of corrupt political system along with peoples representation in functioning of democratic system. But voters be aware that only slogan will not do, we have to give our opinion by casting our vote diligently…. -

Title : Newly Elected Members of 15Th Lok Sabha Took the Oath Or Subscribed the Affirmation

> Title : Newly elected members of 15th Lok Sabha took the oath or subscribed the affirmation. अय महोदय: माननीय सदय, आपको मरण होगा िक जब कल सभा परू े िदन के िलए थिगत हई थी तब शपथ लेने वाले अथवा पितिनिधव करने वाले सदय क सचू ी परू ी नह हो सक थी इसीिलए म महासिचव महोदय से अनुरोध करता हं िक पहले मंितपरषद् के उन सदय के नाम पकु ार जो कल शपथ नह ले सके और पितिनिधव नह कर सके तपात् शपथ लेने व पिता करने के िलए राजथान राय के सदय के नाम पकु ार जाएंग े और उसके बाद शेष राय तथा संघ राय ेत के सदय के नाम पकु ारे जाएंगे SECRETARY-GENERAL: Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal. 11.01 hrs. MEMBERS SWORN − Contd. UTTAR PRADESH Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal (Kanpur) Oath Hindi UTTARAKHAND Shri Harish Rawat (Hardwar) Oath Hindi MAHARASHTRA Shri Prateek Prakash Patil (Sangli) Oath English RAJASTHAN Shri Bharat Ram Meghwal (Ganganagar) Oath Hindi Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal (Bikaner) Oath Hindi Shri Sheesh Ram Ola (Jhunjhunu) Oath Hindi Shri Lal Chand Kataria (Jaipur Rural) Oath Hindi Shri Maheshh Joshi (Jaipur) Oath Hindi Shri Jitendra Singh (Alwar) Oath Hindi Shri Ratan Singh (Bharatpur) Oath Hindi Shri Khiladi Lal Bairwa (Karauli-Dholpur) Oath Hindi Dr. Kirodi Lal (Dausa) Oath Hindi Dr. Jyoti Mirdha (Nagaur) Oath English Shri Badri Ram Jakhar (Pali) Oath Hindi Ms. Chandresh Kumari (Jodhpur) Oath English Shri Harish Choudhary (Barmer) Affirmation Hindi Shri Devji Patel (Jalore) Oath Hindi Shri Raghuvir Singh Meena (Udaipur) Oath Hindi Shri Tarachand Bhagora (Banswara) Oath Hindi Dr. -

12 15. Committee on Home Affairs

15. COMMITTEE ON HOME AFFAIRS (Ministries/Departments : Home Affairs; Development of North-Eastern Region) (Date of Constitution : 31st August, 2009) 1. Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu BJP — Chairman RAJYA SABHA 2. Dr. N. Janardhana Reddy INC 3. Shri Rishang Keishing INC 4. Shri S.S. Ahluwalia BJP 5. Shri Prasanta Chatterjee CPI(M) 6. Shri Brijesh Pathak BSP 7. Dr. V. Maitreyan AIADMK 8. Shri Tariq Anwar NCP 9. Shri D. Raja CPI 10. Vacant LOK SABHA 11. Shri L.K. Advani BJP 12. Dr. Rattan Singh Ajnala SAD 13. Dr. Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar AITC 14. Shri Ramen Deka BJP 15. Shri Mohd. Asrarul Haque INC 16. Shri Naveen Jindal INC 17. Shri Jitender Singh Malik (Sonepat) INC 18. Shri Lalubhai Babubhai Patel BJP 19. Shri Natubhai Gomanbhai Patel BJP 20. Shri L. Rajagopal INC 21. Shri Nilesh Narayan Rane INC 22. Shri Bishnu Pada Ray BJP 23. Shri A. Sampath CPI(M) 24. Shri Hamdullah Sayeed INC 25. Dr. Raghuvansh Prasad Singh RJD 12 26. Shri Ravneet Singh INC 27. Shrimati Seema Upadhyay BSP 28. Shri Harsh Vardhan INC 29. Shri Bhausaheb Rajaram Wakchaure SS &30. Shri Neeraj Shekhar SP 31. Shri Dinesh Chandra Yadav JD(U) & Nominated w.e.f. 13.10.2009 13 16. COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (Ministries/Departments : Human Resource Development; Youth Affairs and Sports; Women and Child Development) (Date of Constitution : 31st August, 2009) 1. Shri Oscar Fernandes INC — Chairman RAJYA SABHA 2. Dr. E.M. Sudarsana Natchiappan INC 3. Shrimati Mohsina Kidwai INC 4. Shri Vijaykumar Rupani BJP 5. Shri M. Rama Jois BJP 6.