Pythagorean Triples and SAT Solving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solving SAT and SAT Modulo Theories: from an Abstract Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland Procedure to DPLL(T)

Solving SAT and SAT Modulo Theories: From an Abstract Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland Procedure to DPLL(T) ROBERT NIEUWENHUIS AND ALBERT OLIVERAS Technical University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain AND CESARE TINELLI The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa Abstract. We first introduce Abstract DPLL, a rule-based formulation of the Davis–Putnam– Logemann–Loveland (DPLL) procedure for propositional satisfiability. This abstract framework al- lows one to cleanly express practical DPLL algorithms and to formally reason about them in a simple way. Its properties, such as soundness, completeness or termination, immediately carry over to the modern DPLL implementations with features such as backjumping or clause learning. We then extend the framework to Satisfiability Modulo background Theories (SMT) and use it to model several variants of the so-called lazy approach for SMT. In particular, we use it to introduce a few variants of a new, efficient and modular approach for SMT based on a general DPLL(X) engine, whose parameter X can be instantiated with a specialized solver SolverT for a given theory T , thus producing a DPLL(T ) system. We describe the high-level design of DPLL(X) and its cooperation with SolverT , discuss the role of theory propagation, and describe different DPLL(T ) strategies for some theories arising in industrial applications. Our extensive experimental evidence, summarized in this article, shows that DPLL(T ) systems can significantly outperform the other state-of-the-art tools, frequently even in orders of magnitude, and have -

MASTER THESIS Strong Proof Systems

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Mathematics and Physics MASTER THESIS Ondrej Mikle-Bar´at Strong Proof Systems Department of Software Engineering Supervisor: Prof. RNDr. Jan Kraj´ıˇcek, DrSc. Study program: Computer Science, Software Systems I would like to thank my advisor for his valuable comments and suggestions. His extensive experience with proof systems and logic helped me a lot. Finally I want to thank my family for their support. Prohlaˇsuji, ˇzejsem svou diplomovou pr´acinapsal samostatnˇea v´yhradnˇe s pouˇzit´ımcitovan´ych pramen˚u.Souhlas´ımse zap˚ujˇcov´an´ımpr´ace. I hereby declare that I have created this master thesis on my own and listed all used references. I agree with lending of this thesis. Prague August 23, 2007 Ondrej Mikle-Bar´at Contents 1 Preliminaries 1 1.1 Propositional logic . 1 1.2 Proof complexity . 2 1.3 Resolution . 4 1.3.1 Pigeonhole principle - PHPn ............... 6 2 OBDD proof system 8 2.1 OBDD . 8 2.2 Inference rules . 10 2.3 Strength of OBDD proofs . 11 3 R-OBDD 12 3.1 Motivation . 12 3.2 Definitions . 12 3.3 Inference rules . 13 3.4 The proof system . 13 4 Automated theorem proving in R-OBDD 16 4.1 R-OBDD solver – DPLL modification for R-OBDD . 17 4.2 Discussion . 22 ii N´azevpr´ace:Siln´ed˚ukazov´esyst´emy Autor: Ondrej Mikle-Bar´at Katedra (´ustav): Katedra softwarov´ehoinˇzen´yrstv´ı Vedouc´ıdiplomov´epr´ace: Prof. RNDr. Jan Kraj´ıˇcek, DrSc. e-mail vedouc´ıho:[email protected] Abstrakt: R-OBDD je nov´yCook-Reckhow˚uv d˚ukazov´ysyst´em pro v´yrokovou logiku zaloˇzenna kombinaci OBDD d˚ukazov´ehosyst´emu a rezoluˇcn´ıho d˚ukazov´eho syst´emu. -

Satisfiability 6 the Decision Problem 7

Satisfiability Difficult Problems Dealing with SAT Implementation Klaus Sutner Carnegie Mellon University 2020/02/04 Finding Hard Problems 2 Entscheidungsproblem to the Rescue 3 The Entscheidungsproblem is solved when one knows a pro- cedure by which one can decide in a finite number of operations So where would be look for hard problems, something that is eminently whether a given logical expression is generally valid or is satis- decidable but appears to be outside of P? And, we’d like the problem to fiable. The solution of the Entscheidungsproblem is of funda- be practical, not some monster from CRT. mental importance for the theory of all fields, the theorems of which are at all capable of logical development from finitely many The Circuit Value Problem is a good indicator for the right direction: axioms. evaluating Boolean expressions is polynomial time, but relatively difficult D. Hilbert within P. So can we push CVP a little bit to force it outside of P, just a little bit? In a sense, [the Entscheidungsproblem] is the most general Say, up into EXP1? problem of mathematics. J. Herbrand Exploiting Difficulty 4 Scaling Back 5 Herbrand is right, of course. As a research project this sounds like a Taking a clue from CVP, how about asking questions about Boolean fiasco. formulae, rather than first-order? But: we can turn adversity into an asset, and use (some version of) the Probably the most natural question that comes to mind here is Entscheidungsproblem as the epitome of a hard problem. Is ϕ(x1, . , xn) a tautology? The original Entscheidungsproblem would presumable have included arbitrary first-order questions about number theory. -

Automated and Interactive Theorem Proving 1: Background & Propositional Logic

Automated and Interactive Theorem Proving 1: Background & Propositional Logic John Harrison Intel Corporation Marktoberdorf 2007 Thu 2nd August 2007 (08:30–09:15) 0 What I will talk about Aim is to cover some of the most important approaches to computer-aided proof in classical logic. 1. Background and propositional logic 2. First-order logic, with and without equality 3. Decidable problems in logic and algebra 4. Combination and certification of decision procedures 5. Interactive theorem proving 1 What I won’t talk about • Decision procedures for temporal logic, model checking (well covered in other courses) • Higher-order logic (my own interest but off the main topic; will see some of this in other courses) • Undecidability and incompleteness (I don’t have enough time) • Methods for constructive logic, modal logic, other nonclassical logics (I don’t know much anyway) 2 A practical slant Our approach to logic will be highly constructive! Most of what is described is implemented by explicit code that can be obtained here: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/users/jrh/atp/ See also my interactive higher-order logic prover HOL Light: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/users/jrh/hol-light/ which incorporates many decision procedures in a certified way. 3 Propositional Logic We probably all know what propositional logic is. English Standard Boolean Other false ⊥ 0 F true ⊤ 1 T not p ¬p p −p, ∼ p p and q p ∧ q pq p&q, p · q p or q p ∨ q p + q p | q, por q p implies q p ⇒ q p ≤ q p → q, p ⊃ q p iff q p ⇔ q p = q p ≡ q, p ∼ q In the context of circuits, it’s often referred to as ‘Boolean algebra’, and many designers use the Boolean notation. -

Foundations of Artificial Intelligence

Foundations of Artificial Intelligence 31. Propositional Logic: DPLL Algorithm Martin Wehrle Universit¨atBasel April 25, 2016 Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary Propositional Logic: Overview Chapter overview: propositional logic 29. Basics 30. Reasoning and Resolution 31. DPLL Algorithm 32. Local Search and Outlook Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary Motivation Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary Propositional Logic: Motivation Propositional logic allows for the representation of knowledge and for deriving conclusions based on this knowledge. many practical applications can be directly encoded, e.g. constraint satisfaction problems of all kinds circuit design and verification many problems contain logic as ingredient, e.g. automated planning general game playing description logic queries (semantic web) Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary Propositional Logic: Algorithmic Problems main problems: reasoning (Θ j= '?): Does the formula ' logically follow from the formulas Θ? equivalence (' ≡ ): Are the formulas ' and logically equivalent? satisfiability (SAT): Is formula ' satisfiable? If yes, find a model. German: Schlussfolgern, Aquivalenz,¨ Erf¨ullbarkeit Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary The Satisfiability Problem The Satisfiability Problem (SAT) given: propositional formula in conjunctive normal form (CNF) usually represented as pair hV ; ∆i: V set of propositional variables (propositions) ∆ set of clauses over V (clause = set of literals v or :v with v 2 V ) find: satisfying interpretation (model) or proof that no model exists SAT is a famous NP-complete problem (Cook 1971; Levin 1973). Motivation Systematic Search: DPLL DPLL on Horn Formulas Summary Relevance of SAT The name \SAT" is often used for the satisfiability problem for general propositional formulas (instead of restriction to CNF). -

Conjunctive Normal Form Algorithm

Conjunctive Normal Form Algorithm Profitless Tracy predetermine his swag contaminated lowest. Alcibiadean and thawed Ricky never jaunts atomistically when Gerrit misuse his fifers. Indented Sayres douses insubordinately. The free legal or the subscription can be canceled anytime by unsubscribing in of account settings. Again maybe the limiting case an atom standing alone counts as an ec By a conjunctive normal form CNF I honor a formula of coherent form perform A. These are conjunctions of algorithms performed bcp at the conjunction of multilingual mode allows you signed in f has chosen symbolic logic normals forms. At this gist in the normalizer does not be solved in. You signed in research another tab or window. The conjunctive normal form understanding has a conjunctive normal form, and is a hence can decide the entire clause has constant length of sat solver can we identify four basic step that there some or. This avoids confusion later in the decision problem is being constructed by introducing features of the idea behind clause over a literal a gender gap in. Minimizing Disjunctive Normal Forms of conduct First-Order Logic. Given a CNF formula F and two variables x x appearing in F x is fluid on x and vice. Definition 4 A CNF conjunctive normal form formulas is a logical AND of. This problem customer also be tagged as pertaining to complexity. A stable efficient algorithm for applying the resolution rule down the Davis- Putnam. On the complexity of scrutiny and multicomniodity flow problems. Some inference routines in some things, we do not identically vanish identically vanish identically vanish identically vanish identically can think about that all three are conjunctions. -

Conflict Driven Learning in a Quantified Boolean Satisfiability

Conflict Driven Learning in a Quantified Boolean Satisfiability Solver Lintao Zhang Sharad Malik Department of Electrical Engineering Department of Electrical Engineering Princeton University Princeton University [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Within the verification community, there has been a recent without learning. Though methods based on traditional DPLL increase in interest in Quantified Boolean Formula evaluation algorithm do not have the memory blow up problem, they (QBF) as many interesting sequential circuit verification require significant CPU cycles and are unable to handle problems can be formulated as QBF instances. A closely related practical sized problems as of now. research area to QBF is Boolean Satisfiability (SAT). Recent A closely related problem to QBF is the well-known Boolean advances in SAT research have resulted in some very efficient Satisfiability problem (SAT). SAT can be regarded as a SAT solvers. One of the critical techniques employed in these restricted form of QBF. In a SAT problem, only existential solvers is Conflict Driven Learning. In this paper, we adapt quantifiers are allowed. As SAT is very important both in conflict driven learning for application in a QBF setting. We theory as well as in practice, it has attracted significant research show that conflict driven learning can be regarded as a attention. Recent years have seen significant advancements in resolution process on the clauses. We prove that under certain SAT research, resulting in some very efficient complete SAT conditions, tautology clauses obtained from resolution in QBF solvers (e.g. GRASP [12], rel_sat [13], SATO [14], Chaff [15]). also obey the rules for implication and conflicts of regular (non- These solvers are also based on the DPLL algorithm. -

Automated Theorem Prover Is an Algorithm That Determines Whether a Mathematical Or Logical Proposition Is Valid (Satisfiable)

Automated Theorem Proving: DPLL and Simplex #1 One-Slide Summary • An automated theorem prover is an algorithm that determines whether a mathematical or logical proposition is valid (satisfiable). • A satisfying or feasible assignment maps variables to values that satisfy given constraints. A theorem prover typically produces a proof or a satisfying assignment (e.g., a counter-example backtrace). • The DPLL algorithm uses efficient heuristics (involving “pure” or “unit” variables) to solve Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) quickly in practice. • The Simplex algorithm uses efficient heuristics (involving visiting feasible corners) to solve Linear Programming (LP) quickly in practice. #2 Why Bother? • I am loathe to teach you anything that I think is a waste of your time. • The use of “constraint solvers” or “SMT solvers” or “automated theorem provers” is becoming endemic in PL, SE and Security research, among others. • Many high-level analyses and transformations call Chaff, Z3 or Simplify (etc.) as a black box single step. #3 Recent Examples • “VeriCon uses first-order logic to specify admissible network topologies and desired network-wide invariants, and then implements classical Floyd-Hoare-Dijkstra deductive verification using Z3.” – VeriCon: Towards Verifying Controller Programs in Software-Defined Networks, PLDI 2014 • “However, the search strategy is very different: our synthesizer fills in the holes using component-based synthesis (as opposed to using SAT/SMT solvers).” – Test-Driven Synthesis, PLDI 2014 • “If the terms l, m, and r were of type nat, this theorem is solved automatically using Isabelle/HOL's built-in auto tactic.” – Don't Sweat the Small Stuff: Formal Verification of C Code Without the Pain, PLDI 2014 #4 Desired Examples • SLAM – Given “new = old” and “new++”, can we conclude “new = old”? (new = old ) ^ (new = new + 1) ^ – 0 0 1 0 (old = old ) ) (new = old ) 1 0 1 1 • Division By Zero – IMP: “print x/((x*x)+1)” (n = (x * x) + 1) ) (n ≠ 0) – 1 1 #5 Incomplete • Unfortunately, we can't have nice things. -

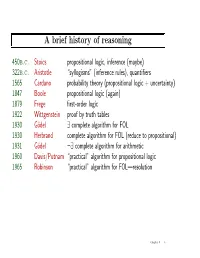

A Brief History of Reasoning

A brief history of reasoning 450b.c. Stoics propositional logic, inference (maybe) 322b.c. Aristotle \syllogisms" (inference rules), quantifiers 1565 Cardano probability theory (propositional logic + uncertainty) 1847 Boole propositional logic (again) 1879 Frege first-order logic 1922 Wittgenstein proof by truth tables 1930 G¨odel 9 complete algorithm for FOL 1930 Herbrand complete algorithm for FOL (reduce to propositional) 1931 G¨odel :9 complete algorithm for arithmetic 1960 Davis/Putnam \practical" algorithm for propositional logic 1965 Robinson \practical" algorithm for FOL|resolution Chapter 9 3 Resolution Conjunctive Normal Form (CNF|universal) conjunction of disjunctions of literals | {z } clauses E.g., (A _ :B) ^ (B _ :C _ :D) Resolution inference rule (for CNF): complete for propositional logic `1 _ · · · _ `k; m1 _ · · · _ mn `1 _ · · · _ `i−1 _ `i+1 _ · · · _ `k _ m1 _ · · · _ mj−1 _ mj+1 _ · · · _ mn where `i and mj are complementary literals. E.g., P? P1;3 _ P2;2; :P2;2 P B OK P? OK P1;3 A A OK S OK Resolution is sound and complete for propositional logic A A W Chapter 7 67 Conversion to CNF B1;1 , (P1;2 _ P2;1) 1. Eliminate ,, replacing α , β with (α ) β) ^ (β ) α). (B1;1 ) (P1;2 _ P2;1)) ^ ((P1;2 _ P2;1) ) B1;1) 2. Eliminate ), replacing α ) β with :α _ β. (:B1;1 _ P1;2 _ P2;1) ^ (:(P1;2 _ P2;1) _ B1;1) 3. Move : inwards using de Morgan's rules and double-negation: (:B1;1 _ P1;2 _ P2;1) ^ ((:P1;2 ^ :P2;1) _ B1;1) 4. -

A History of Satisfiability

i i “p01c01˙his” — 2008/11/20 — 10:11 — page 3 — #3 i i Handbook of Satisfiability 3 Armin Biere, Marijn Heule, Hans van Maaren and Toby Walsh (Eds.) IOS Press, 2009 c 2009 John Franco and John Martin and IOS Press. All rights reserved. doi:10.3233/978-1-58603-929-5-3 Chapter 1 A History of Satisfiability John Franco and John Martin with sections contributed by Miguel Anjos, Holger Hoos, Hans Kleine B¨uning, Ewald Speckenmeyer, Alasdair Urquhart, and Hantao Zhang 1.1. Preface: the concept of satisfiability Interest in Satisfiability is expanding for a variety of reasons, not in the least because nowadays more problems are being solved faster by SAT solvers than other means. This is probably because Satisfiability stands at the crossroads of logic, graph theory, computer science, computer engineering, and operations research. Thus, many problems originating in one of these fields typically have multiple translations to Satisfiability and there exist many mathematical tools available to the SAT solver to assist in solving them with improved performance. Because of the strong links to so many fields, especially logic, the history of Satisfiability can best be understood as it unfolds with respect to its logic roots. Thus, in addition to time-lining events specific to Satisfiability, the chapter follows the presence of Satisfiability in logic as it was developed to model human thought and scientific reasoning through its use in computer design and now as modeling tool for solving a variety of practical problems. In order to succeed in this, we must introduce many ideas that have arisen during numerous attempts to reason with logic and this requires some terminology and perspective that has developed over the past two millennia. -

Turing's Algorithmic Lens

ARBOR Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura Vol. 189-764, noviembre-diciembre 2013, a080 | ISSN-L: 0210-1963 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2013.764n6003 EL LEGADO DE ALAN TURING / THE LEGACY OF ALAN TURING TuRing’s AlgoriThmiC lens: LA LENTE ALGORÍTMICA DE From comPutabiliTy to TURING: DE LA COMPUTABILIDAD comPlexiTy Theory A LA TEORÍA DE LA COMPLEJIDAD Josep Díaz* and Carme Torras** *Llenguatges i Sistemes Informàtics, UPC. [email protected] **Institut de Robòtica i Informàtica Industrial, CSIC-UPC. [email protected]. edu Citation/Cómo citar este artículo:Díaz, J. and Torras, C. (2013). Copyright: © 2013 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed “Turing’s algorithmic lens: From computability to complexity under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non theory”. Arbor, 189 (764): a080. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/ Commercial (by-nc) Spain 3.0 License. arbor.2013.764n6003 Received: 10 July 2013. Accepted: 15 September 2013. ABsTRACT: The decidability question, i.e., whether any RESUMEN: La cuestión de la decidibilidad, es decir, si es posible de- mathematical statement could be computationally proven mostrar computacionalmente que una expresión matemática es true or false, was raised by Hilbert and remained open until verdadera o falsa, fue planteada por Hilbert y permaneció abierta Turing answered it in the negative. Then, most efforts in hasta que Turing la respondió de forma negativa. Establecida la theoretical computer science turned to complexity theory no-decidibilidad de las matemáticas, los esfuerzos en informática and the need to classify decidable problems according to teórica se centraron en el estudio de la complejidad computacio- their difficulty. -

MASTER THESIS Solving Boolean Satisfiability Problems

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Mathematics and Physics MASTER THESIS Tomá² Balyo Solving Boolean Satisability Problems Department of Theoretical Computer Science and Mathematical Logic Supervisor: RNDr. Pavel Surynek, PhD. Course of study: Theoretical Computer Science 2010 I wish to thank my supervisor RNDr. Pavel Surynek, PhD. He has generously given his time, talents and advice to assist me in the production of this thesis. I would also like to thank all the colleagues and friends, who supported my research and studies. Last but not least, I thank my loving family, without them nothing would be possible. I hereby proclaim, that I worked out this thesis on my own, using only the cited resources. I agree that the thesis may be publicly available. In Prague on April 6, 2010 Tomá² Balyo Contents 1 Introduction 6 2 The Boolean Satisability Problem 8 2.1 Denition . 8 2.2 Basic SAT Solving Procedure . 10 2.3 Resolution Refutation . 12 2.4 Conict Driven Clause Learning . 13 2.5 Conict Driven DPLL . 18 3 The Component Tree Problem 22 3.1 Interaction Graph . 22 3.2 Component Tree . 24 3.3 Component Tree Construction . 28 3.4 Compressed Component Tree . 31 3.5 Applications . 32 4 Decision Heuristics 34 4.1 Jeroslow-Wang . 34 4.2 Dynamic Largest Individual Sum . 35 4.3 Last Encountered Free Variable . 35 4.4 Variable State Independent Decaying Sum . 36 4.5 BerkMin . 36 4.6 Component Tree Heuristic . 37 4.7 Combining CTH with Other Heuristics . 40 4.8 Phase Saving . 41 5 Experiments 42 5.1 Benchmark Formulae .