Redalyc.Bromeliad Ornamental Species: Conservation Issues And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing Alcantarea

Bromeliaceae VOLUME XLII - No. 3 - MAY/JUNE 2008 The Bromeliad Society of Queensland Inc. P. O. Box 565, Fortitude Valley Queensland, Australia 4006, Home Page www.bromsqueensland.com OFFICERS PRESIDENT Olive Trevor (07) 3351 1203 VICE PRESIDENT Anne McBurnie PAST PRESIDENT Bob Reilly (07) 3870 8029 SECRETARY Chris Coulthard TREASURER Glenn Bernoth (07) 4661 3 634 BROMELIACEAE EDITOR Ross Stenhouse SHOW ORGANISER Bob Cross COMMITTEE Greg Aizlewood, Bruce Dunstan, Barry Kable, Arnold James,Viv Duncan, David Rees MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Roy Pugh (07) 3263 5057 SEED BANK CO-ORDINATOR Doug Parkinson (07) 5497 5220 AUDITOR Anna Harris Accounting Services SALES AREA CASHIER Norma Poole FIELD DAY CO-ORDINATOR Ruth Kimber & Bev Mulcahy LIBRARIAN Evelyn Rees ASSISTANT SHOW ORGANISER Phil Beard SUPPER STEWARDS Nev Ryan, Barry Genn PLANT SALES Pat Barlow Phil James COMPETITION STEWARDS Dorothy Cutcliffe, Arnold James CHIEF COMPETITION STEWARD HOSTESS Gwen Parkinson BSQ WEBMASTER Ross Stenhouse LIFE MEMBERS Grace Goode OAM Peter Paroz, Michael O’Dea Editors Email Address: [email protected] The Bromeliad Society of Queensland Inc. gives permission to all Bromeliad Societies to re- print articles in their journals provided proper acknowledgement is given to the original author and the Bromeliaceae, and no contrary direction is published in Bromeliaceae. This permission does not apply to any other person or organisation without the prior permission of the author. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the individual contributor and may not neces- sarily reflect the opinions of the Bromeliad Society of Queensland or of the Editor Authors are responsible for the accuracy of the information in their articles. -

Biodiversidade Brasileira Número Temático Manejo Do Fogo Em Áreas Protegidas Editorial

Editorial 1 Biodiversidade Brasileira Número Temático Manejo do Fogo em Áreas Protegidas Editorial Katia Torres Ribeiro1, Helena França2, Heloísa Sinatora Miranda3 & Christian Niel Berlinck4 Neste segundo número de Biodiversidade Brasileira trazemos ampla e variada discussão sobre o manejo do fogo em áreas protegidas. Abrimos assim a segunda linha editorial da revista, que visa à publicação dos resultados técnico-científicos do processo de avaliação do estado de conservação das espécies bem como, na forma de números temáticos, a discussão, entre pesquisadores de diversas áreas e gestores, de temas críticos relacionados à conservação e ao manejo. A dimensão alcançada pelos incêndios em áreas naturais, rurais e urbanas do Brasil no ano de 2010 explicitou à sociedade, mais uma vez, a situação dramática e quase cotidiana em grande parte do país, no que diz respeito ao fogo. É claro que a situação pregressa e a atual não são admissíveis. No entanto, tem-se cada vez maior clareza de que a resposta ao emprego do fogo no Brasil, com sua tamanha complexidade, não pode se pautar apenas na proibição do seu uso e no combate aos focos que ocorrerem. A situação é mais complexa – o fogo é ainda ferramenta importante em muitas áreas rurais, do ponto de vista sócio-econômico, mesmo considerando o investimento em novas tecnologias, além de ser uma expressão de conflitos diversos. Seu uso pode ser, em alguns contextos, eventualmente preferível em comparação com outras opções acessíveis de trato da terra, e há ainda situações em que seu emprego intencional pode ser recomendável como ferramenta de manejo de áreas protegidas. É preciso investir na consolidação da informação, disseminação do conhecimento e discussão para que possamos, como sociedade e governo, ter uma visão mais completa do fenômeno ‘fogo’ no país, considerando a complexidade de ecossistemas, paisagens, e contextos sócio-econômicos, de modo a construir boas estratégias de manejo. -

BROMELIACEAE (Bromeliad Family)

Name: ___________________________________ Due: Wednesday, July 11th BROMELIACEAE (Bromeliad family) • 51 genera; 1520 species • Herbs, often epiphytic • Hairs as water-absorbing peltate scales, or occasionally stellate • Leaves alternate, often forming water ‘tanks’ at leaf base, simple, entire to sharply serrate, with parallel venation, water storage tissue, sheathing leaf bases; stipules absent • Flowers bisexual, actinomorphic; sepals 3, free or connate; petals 3, free or connate, often with paired appendages at base; stamens 6; filaments free or connate, sometimes epipetalous; carpels 3, connate; ovary superior to inferior, with axile placentation; stigmas 3, usually spirally twisted; ovules numerous • Fruit a capsule or berry; seeds often winged or with tuft of hair • Examples: Ananas comosus (pineapple), Guzmania, Tillandsia (spanish moss), Vriesia Greenhouse If you have time there’s lots of cool orchids in Room 2, but if you’re here only for the Bromeliads head down to Room 5. Room 5 As you walk in the wall on the right holds many epiphytic bromeliads, mostly Tillandsia (spanish moss). Does it look familiar? Note the orchid blooming on the table in front of you, hanging above the sign 5-1. Follow along the wall of Tillandsia to the back of the room. Note the bromeliads on your left as you walk. You should see Neoregelia, with some red leaves amidst the mainly green ones. Note how the infloresence is in the shallow depression holding water at the center of the plant. There may be a few flowers actually opening. Be sure to stop and look at the pineapple (Ananas comosus), it’s in fruit now, we’ve missed the flowers. -

C:\Users\HERB\MY FILES\BROMELIANA RECENT

BROMELI ANA PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK BROMELIAD SOCIETY (visit our website www.nybromeliadsociety.org) November, 2012 Volume 49, No. 8 THE 2012 WORLD BROMELIAD CONFERENCE IN ORLANDO by Herb Plever “Kaleidoscope of Peter Bak who runs the giant Bak Bromeliads”, the 20th World nursery in Amsterdam gently chided Bromeliad Conference was held at me for my article lamenting the the Caribe Royale Hotel from disappearance of Vriesea splendens. He September 24th to October 1st in said there were many growers selling Orlando, FL. It was the third time V. splendens in Europe. the world conference was held there; One great surprise gave me this time the official host was the special joy when I was able to greet Florida Council of Bromeliad and hug Don Beadle, a good friend Societies, but the local Bromeliad who has quietly returned to working Society of Central Florida did most with bromeliads in Michael Kiehl’s of the hard work in putting on a nursery in Venice, FL. Don had conference and did it well (except for owned that facility and sold it to the too large venue of the auction Michael for personal reasons. Don and the frigid conditions at the Don Beadle and Joann in Orlando left the fold to live with his true love banquet). The conference was on a river boat; those of us who attended by about 300 people, mostly from the United knew him wished him well. When the suppressed brom States, but many registrants were from abroad. bug emerged, Joann made it possible for him to be both Although this WBC was held in late September, personally and billbergia happy. -

Aesthetics of Bromeliads

Design and layout © Photo-syn-thesis 2015 Applicable text © Lloyd Godman Photographs © Lloyd Godman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or means, whether electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Please email for permission. Published by Photo-syn-thesis - 2015 www.lloydgodman.net [email protected] mob. Australia - 0448188899 some thoughts on the Aesthetics of Bromeliads Lloyd Godman http://www2.estrellamountain.edu/faculty/farabee/BIOBK/ BioBookPS.html 30/5/2015 Introduction Responding to colour, and form, humans are créatures visuelles. It is no surprise then that the wildly diverse variations of leaf colour, shape and structural form in plants from the family Bromeliaceae (Bromeliads) for many admirers prove irre- sistibly intriguing and captivating. A little research reveals that this amazing family of plants are indeed credited with offering the widest range of variation of colour and shape within any plant family. This is not only witnessed this in the leaf, but also in the colours and shapes of the appendages associated with flowering. Beyond the seductive visuals, an understanding of the fascinating biology Brome- liads have evolved, reveals complex systems far advanced from the first plants that emerged on land during the Ordovician period, around 450 million years ago. In fact, even the earliest examples within the family are very recent arrivals to the 1 kingdom plantea appearing but 70-50 million years ago with many of the 3,000 species evolving just 15 million years ago; about the same time as primates began to populate the planet. -

Catalogue of Bromeliad Literature March 2001

Catalogue of Bromeliad Literature march 2001 Contains titles of books, dissertations and a selection of recent articles from journals; also included are flora's in which the Bromeliaceae are described. Additions and corrections are welcomed by Leo Dijkgraaf E-mail [email protected] CATALOGUE - authors in alphabetical order Acevedo-Rodriguez, P. - Bromeliaceae, In: Flora of St.John, U.S. Virgin Islands. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden Vol.78, USA 1996 ISBN 0-89327-402-X ( page 467-472; total 581 pages, 27 cm ). Adams, C. D. : see Proctor, G. R. Adams, W. W. & Martin, C. E. - Heterophylly and its relevance to evolution within the Tillandsioideae. Selbyana 9:121-125 1986. Anderson, W. R. : see McVaugh, R. André, E. - Bromeliaceae Andreanae. Description et Histoire des Bromeliacées, récoltées dans la Colombie, l'Ecuador et la Venezuela. Librairie Agricole, Paris France 1889 ( 118 pages, 40 bw. plates). English translation with annotations by M. Rothenberg : Bromeliaceae Andreanae. Big Bridge / Twowindows Press, Berkeley USA 1983 ( 211 pages, 40 bw.plates, 24x31 cm ). More about André in Journal of the Bromeliad Society 33(2):56-65 1983 and in vol. 45(1):27-29 1995 for a list of species collected by André. Antoine, F. - Phyto-Iconographie der Bromeliaceen des kaiserlichen königlichen Hofburg-Gartens in Wien. Gerold & Comp., Vienna Austria 1884 ( 35 illustrations, 54 pages ). Arrais, M. - Aspectos anatômicos de espécies de Bromeliaceae da Serra do Cipó-MG, com especial referência à vascularizaçâo floral. Thesis, Sao Paulo Brazil 1989. Baensch, U. & U. - Blühende Bromelien. Tropic Beauty Publishers (Nassau, Bahamas) & Tetra Verlag (Melle, Germany) 1994 ISBN 1-56465-148-7. -

Seedling Ecology and Evolution

P1: SFK 9780521873053pre CUUK205/Leck et al. 978 0 521 87305 5 June 26,2008 16:55 Seedling Ecology and Evolution Editors Mary Allessio Leck Emeritus Professor of Biology,Rider University,USA V. Thomas Parker Professor of Biology,San Francisco State University,USA Robert L. Simpson Professor of Biology and Environmental Science,University of Michigan -- Dearborn,USA iii P1: SFK 9780521873053pre CUUK205/Leck et al. 978 0 521 87305 5 June 26,2008 16:55 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, S˜ao Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521873055 c Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2008 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-521-87305-5 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-69466-7 paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. iv P1: SFK 9780521873053c04 CUUK205/Leck et al. -

FAVORETO.FC.2013. Vfinal

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA MESTRADO EM ECOLOGIA APLICADA AO MANEJO E CONSERVAÇÃO DE RECURSOS NATURAIS Fernanda Campanharo Favoreto FLORÍSTICA, SIMILARIDADE E CONSERVAÇÃO DE BROMELIACEAE EM UM TRECHO DO CORREDOR CENTRAL DA MATA ATLÂNTICA NO ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO, BRASIL JUIZ DE FORA 2013 Fernanda Campanharo Favoreto FLORÍSTICA, SIMILARIDADE E CONSERVAÇÃO DE BROMELIACEAE EM UM TRECHO DO CORREDOR CENTRAL DA MATA ATLÂNTICA NO ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO, BRASIL Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação de Recursos Naturais da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Ecologia Aplicada ao Manejo e Conservação de Recursos Naturais Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Ana Paula Gelli de Faria. Juiz de Fora - MG Maio de 2013 II III IV AGRADECIMENTOS Em primeiro lugar gostaria de chamar a atenção a esta seção, pois é onde a verdadeira metodologia da pesquisa aparece, a metodologia das parcerias, amizades e colaborações que fazem a ciência acontecer. Não afirmo que as teorias, técnicas e referências não sejam importantes, mas o que permitiu, de verdade, a idealização, realização e a atual conclusão do presente trabalho, aparece aqui. Agradeço em primeiro lugar a Deus, que refrigera a alma nos momentos difíceis, que com certeza me segurou em algumas pirambeiras, que distraiu algumas cobras, que desviou meus olhos de muitos acúleos e permitiu que eu encontrasse todas essas outras pessoas. Agradeço aos meus pais e toda a minha família. Este MUITO OBRIGADA não é só pelo carinho, pela ajuda no cotidiano pessoal, apoio moral e à minha formação (o que não é pouca coisa), mas também pela contribuição significativa aos resultados alcançados. -

2018 Fcbs Officers

FLORIDA COUNCIL OF Volume 38 Issue 3 BROMELIAD SOCIETIES August 2018 Ananas ananassioides var nanas x Ananas Erectifolius Page FLORIDA COUNCIL OF BROMELIAD SOCIETIES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents..………………………………………………………………………………2 2018 FCBS Officers and Representatives, Committee Members, Florida BSI Officers……….3 I love Bromeliads by Carol Wolfe………………………………………………………………4 Mexican Bromeliad Weevil Report by Teresa Marie Cooper…………………………………..5 BSI Honorary Trustee by Tom Wolfe……….………………………………………………….7 B.L.B.E.R.J.R. by Don Beadle……..…..……………………………………………………… 8 Don Beadle, BSI Honorary Trustee by Lynn Wagner..……………………….………………..9 2018 BSI World Conference in San Diego, California by Jay Thurrott...…………………….11 Bromeliad Expedition in the Everglades by Mike Michalski………………………………….14 2018 WBC Pictures by Mike Michalski…………..…………………………………………...15 Edmundoa by Derek Butcher………………………...…...……………………………………16 Fitting 2000 + Bromeliads and a home into a Quarter acre city lot; Bromeliad Everywhere! By Terrie Bert …………………………………………………………………..18 BSI Archives by Stephen Provost...…………………………………………………………...27 Bromeliad Society of Central Florida Annual Show & Sale by Carol Wolfe………….……...29 Photographing Bromeliads by John Catlen……………….…………………………………...35 Calendar of Events……………………………… ……………………………………….…...38 Seminole Bromeliad & Tropical Plant Society…………..……………………………………39 PUBLICATION: This newsletter is published four times a year, February, May, August, and November, and is a publication of the Florida Council of Bromeliad Societies. Please submit your -

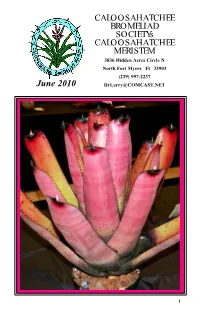

June 2010 [email protected]

CALOOSAHATCHEE BROMELIAD SOCIETYs CALOOSAHATCHEE MERISTEM 3836 Hidden Acres Circle N North Fort Myers Fl 33903 (239) 997-2237 June 2010 [email protected] 1 CALOOSAHATCHEE BROMELIAD SOCIETY OFFICERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE PRESIDENT Eleanor Kinzie ([email protected]) VICE-PRESIDENT John Cassani ([email protected]) SECRETARY Ross Griffith TREASURER Betty Ann Prevatt ([email protected]) PAST-PRESIDENT Donna Schneider ([email protected]) STANDING COMMITTEES CHAIRPERSONS NEWSLETTER EDITOR Larry Giroux ([email protected]) FALL SALES CHAIR Brian Weber FALL SALES Co-CHAIR PROGRAM CHAIRPERSON Bruce McAlpin WORKSHOP CHAIRPERSON Steve Hoppin ([email protected]) SPECIAL PROJECTS Gail Daneman ([email protected]) CBS FCBS Rep. Vicky Chirnside ([email protected]) CBS FCBS Rep. OTHER COMMITTEES AUDIO/VISUAL SETUP Bob Lura, Terri Lazar and Vicki Chirnside DOOR PRIZE Terri Lazar ([email protected]) HOSPITALITY Mary McKenzie; Sue Gordon SPECIAL HOSPITALITY Betsy Burdette ([email protected]) RAFFLE TICKETS Greeter/Membership table volunteers - Dolly Dalton, Luli Westra RAFFLE COMMENTARY Larry Giroux GREETERS/ATTENDENCE Betty Ann Prevatt, Dolly Dalton ([email protected]), Luli Westra SHOW & TELL Dale Kammerlohr ([email protected]) FM-LEE GARDEN COUNCIL Mary McKenzie LIBRARIAN Kay Janssen The opinions expressed in the Meristem are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or the official policy of CBS. Permission to reprint is granted with acknowledgement. Original art work remains the property of the artist and special permission may be needed for reproduction. Although the highly colorful and patterned neoregelias are very popular among bromeliad collectors, the “Neoregelia carcharadon Group” of plants are unique, easy to care for and sun tolerate, albeit more adaptable to the landscape, they also deserve a place in your collection. -

Tese 11486 90-Waldesse Storch Rosa.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO CENTRO UNIVERSITÁRIO NORTE DO ESPÍRITO SANTO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIODIVERSIDADE TROPICAL WALDESSE STORCH ROSA DESEMPENHO DO APARATO FOTOSSINTÉTICO EM FUNÇÃO DAS CITOCININAS EMPREGADAS DURANTE A FASE DE MULTIPLICAÇÃO in vitro DE Aechmea blanchetiana (BROMELIACEAE) SÃO MATEUS, ES 2017 WALDESSE STORCH ROSA DESEMPENHO DO APARATO FOTOSSINTÉTICO EM FUNÇÃO DAS CITOCININAS EMPREGADAS DURANTE A FASE DE MULTIPLICAÇÃO in vitro DE Aechmea blanchetiana (BROMELIACEAE) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós–Graduação em Biodiversidade tropical da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Biodiversidade, na área de concentração Ecofisiologia Vegetal. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Antelmo Ralph Falqueto. Coorientadores: Prof. Dra. Andréia Barcelos Passos Lima Gontijo; Dr. João Paulo Rodrigues Martins. SÃO MATEUS, ES 2017 WALDESSE STORCH ROSA DESEMPENHO DO APARATO FOTOSSINTÉTICO EM FUNÇÃO DAS CITOCININAS EMPREGADAS DURANTE A FASE DE MULTIPLICAÇÃO in vitro DE Aechmea blanchetiana (BROMELIACEAE) Dissertação apresentada ao programa de Pós- Graduação em Biodiversidade tropical da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biodiversidade Tropical. A minha digníssima esposa Suéli e aos meus amados filhos Kárlyon e Micaély, por ser a razão de minha vida. A minha querida e amada mãe Irene por ter me dado o dom da vida. Dedico. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Deus pelo carinho, cuidado e por me permitir viver até a concretização deste momento importante em minha vida. Foram muitas horas de dedicação, dificuldades e incertezas, mas, jamais poderei eu negar a Tua companhia comigo me dando a força necessária para alcançar o meu objetivo. -

Florida Council of Bromeliad Societies, Inc

Florida Council of Bromeliad Societies, Inc. In this issue: Harry Luther Don Beadle Maturity/Immaturity in Bromeliads Vol. 32 Issue 4 November 2012 FCBS Affiliated Societies and Representatives Bromeliad Guild of Tampa Bay Tom Wolfe (813) 961-1475 [email protected] Eileen Hart (813) 920-2987 [email protected] Bromeliad Society of Broward County Jose Donayre (954) 925-5112 [email protected] Sara Donayre (954) 925-5112 [email protected] Bromeliad Society of Central Florida Lisa Robinette (321) 303-7615 [email protected] Ben Klugh (407-833-9494) [email protected] Bromeliad Society of South Florida Michael Michalski (305) 279-2416 [email protected] Patty Gonzalez (305) 279-2416 [email protected] Caloosahatchee Bromeliad Society Vicky Chirnside (941) 493-5825 [email protected] Florida East Coast Bromeliad Society Calandra Thurrott (386) 761-4804 [email protected] Steven Provost (368) 428-9687 [email protected] Florida West Coast Bromeliad Society Ashley Graham (727) 501-2872 [email protected] Susan Sousa (727) 391-5455 [email protected] (continued on the inside back cover) 2013 Bromeliad Extravaganza! Sponsored by the Florida Council of Bromeliad Societies Hosted by Florida West Coast Bromeliad Society September 21 Holiday Inn Harborside 401 2nd Street, Indian Rocks Beach 33785 727-595-9484 Information contacts: Susan Sousa [email protected] Judy Lund [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Catching Up, Staying Even..………………………… …. 3 Affiliated Society News ...………………………...……. 5 Thank You, Gainesville …………………………………. 7 Harry Luther .….……………..………………………….. 8 Calendar ……………………………………………….. 11 Don Beadle ………………….…………….…………... 12 The Beadle Collection ………….……………………….16 Maturity/Immaturity in Bromeliads …………………… 17 Al Muzzell Memorial Garden ……………….………… 19 Brazil Journey……………………………….………….. 20 Mexican Bromeliad Weevil Report …………………….