Seedling Ecology and Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Seed Ecology Iii

SEED ECOLOGY III The Third International Society for Seed Science Meeting on Seeds and the Environment “Seeds and Change” Conference Proceedings June 20 to June 24, 2010 Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Editors: R. Pendleton, S. Meyer, B. Schultz Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Preface Extended abstracts included in this proceedings will be made available online. Enquiries and requests for hardcopies of this volume should be sent to: Dr. Rosemary Pendleton USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque Forestry Sciences Laboratory 333 Broadway SE Suite 115 Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA 87102-3497 The extended abstracts in this proceedings were edited for clarity. Seed Ecology III logo designed by Bitsy Schultz. i June 2010, Salt Lake City, Utah Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Table of Contents Germination Ecology of Dry Sandy Grassland Species along a pH-Gradient Simulated by Different Aluminium Concentrations.....................................................................................................................1 M Abedi, M Bartelheimer, Ralph Krall and Peter Poschlod Induction and Release of Secondary Dormancy under Field Conditions in Bromus tectorum.......................2 PS Allen, SE Meyer, and K Foote Seedling Production for Purposes of Biodiversity Restoration in the Brazilian Cerrado Region Can Be Greatly Enhanced by Seed Pretreatments Derived from Seed Technology......................................................4 S Anese, GCM Soares, ACB Matos, DAB Pinto, EAA da Silva, and HWM Hilhorst -

Ascarina Lucida Var. Lanceolata

Ascarina lucida var. lanceolata COMMON NAME Kermadec Islands Hutu SYNONYMS Ascarina lanceolata Hook.f. FAMILY Chloranthaceae AUTHORITY Ascarina lucida var. lanceolata (Hook.f.) Allan FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No Hutu. Photographer: Bec Stanley ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE ASCLVL CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 26 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS Hutu. Photographer: Bec Stanley 2012 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: IE, OL PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: IE, OL 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Small bushy tree of upland Kermadec Islands. Leaves narrow and tapering to a narrow tip and with coarse black- tipped teeth on margins. Flowers in clusters of spikes. Fruit small, white. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. Kermadec Islands, Raoul Island only. HABITAT One of the characteristic trees of the wet forests of Raoul Island which are mostly found above 245m. However, in the ravines this tree may extend down to almost sea level. In the wet forest it is mostly a subcanopy tree which co- associates with Coprosma acutifolia, Pseudopanax kermadecensis, Melicytus aff. ramiflorus and on occasion Boehmeria australis subsp. dealbata. Occasionally, such as on the ridge lines and crater rim it may form part of the forest canopy. FEATURES Glabrous gynodioecious tree up to 15 m tall. Trunk up to 500 mm diameter. Bark greyish-white. Branchlets slender, striate, initially pale green maturing dark green to emerald green. Interpetiolar stipules conspicuous, comprising 3 1.2-2.6 mm long pale pink to red, filaments; these connate near base, behind which are 3-6 smaller hyaline filaments. Petioles up to 15-20 mm long, lamina subcoriacous, somewhat fleshy, 50-100 × 10-30 mm, green, emerald green to dark green above, paler beneath, serrations weakly pigmented, pink to pale maroon often fading into pale pink spotting, narrowly lanceolate, lanceolate, lanceolate- oblong to narrowly elliptic, acuminate to acute. -

On the Fringe Journal of the Native Plant Society of Northeastern Ohio

On The Fringe Journal of the Native Plant Society of Northeastern Ohio ANNUAL DINNER Friday, October 22 2004 At the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Socializing and dinner: 5:30 Lecture by Dr. Kathryn Kennedy at 7:30 “Twenty Years of Recovering America’s Vanishing Flora” This speaker is co-sponsored by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Explorer Series. Tickets: Dinner and lecture: $20.00. Send checks to Ann Malmquist, 6 Louise Drive., Chagrin Falls, OH 44022; 440-338-6622 Tickets for the lecture only: $8.00, purchased through the Museum TICKETS ARE LIMITED, SO MAKE YOUR RESERVATIONS EARLY Annual Dinner Speaker Mark your calendars now! Come and enjoy hearing Dr. Kathryn Kennedy, President of the Center for about the detective work that goes into finding and Plant Conservation, will speak at the Annual Dinner on identifying rare plants and the exciting experimentation Twenty Years of Recovering America’s Vanishing of reproducing them for posterity. Remember: Flora. Extinction is forever. The CPC was begun because our native plants are declining at an alarming rate. Among them are some of Ohio Botanical Garden the most beautiful and useful species on earth. The On July 12th Jane Rogers and I were privileged to be implications of this trend are stunning. The importance guests of Ohio’s First Lady, Hope Taft, at the of plants to life on Earth is immeasurable. The Governor’s Residence in Columbus. Mrs. Taft, an landscapes we cherish, the food we eat, even the very NPSNEO member, was giving us a guided tour of the air we breathe is connected to plant life. -

Willi Orchids

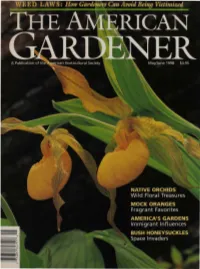

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Acacia Fimbriata Dwarf Crimson Blush 8 Eye on It During the Conference, Please Let Me Know

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) Inc. ACACIA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER Group Leader and Newsletter Editor Seed Bank Curator Bill Aitchison Victoria Tanner 13 Conos Court, Donvale, Vic 3111 Phone (03) 98723583 Email: [email protected] No. 129 June 2015 ISSN 1035-4638 Contents Page From The Leader Dear Members From the Leader 1 It is now only a few months until the ANPSA Biennial Welcome 2 Conference being held in Canberra from 15-20 November. From Members and Readers 2 This is a great opportunity to catch up with some other Some Notes From Yallaroo 3 members of our Study Group, and of course to take part in Wattles With Minni Ritchi Bark 5 the great program put together by the organisers. Introduction of Australian Acacias Information relating to the Conference and details regarding to South America 6 registration are available on the Conference website Max’s Interesting Wattles 7 http://anpsa.org.au/conference2015. Our Study Group will An Acacia dealbata question from have a display at the Conference. If any Study Group Sweden 7 member who will be at the Conference could help with the Pre-treatment of Acacia Seeds 8 display, either in setting it up, or just in helping to keep an Acacia fimbriata dwarf Crimson Blush 8 eye on it during the Conference, please let me know. Books 9 Seed Bank 9 I am sure that many of our members will be aware of the Study Group Membership 10 Wattle Day Association, and the great work that it does in promoting National Wattle Day each year on 1 September. -

Native Plants Sixth Edition Sixth Edition AUSTRALIAN Native Plants Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SIXTH EDITION SIXTH EDITION AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation John W. Wrigley Murray Fagg Sixth Edition published in Australia in 2013 by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Reed New Holland an imprint of New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Sydney • Auckland • London • Cape Town Many people have helped us since 1977 when we began writing the first edition of Garfield House 86–88 Edgware Road London W2 2EA United Kingdom Australian Native Plants. Some of these folk have regrettably passed on, others have moved 1/66 Gibbes Street Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia to different areas. We endeavour here to acknowledge their assistance, without which the 218 Lake Road Northcote Auckland New Zealand Wembley Square First Floor Solan Road Gardens Cape Town 8001 South Africa various editions of this book would not have been as useful to so many gardeners and lovers of Australian plants. www.newhollandpublishers.com To the following people, our sincere thanks: Steve Adams, Ralph Bailey, Natalie Barnett, www.newholland.com.au Tony Bean, Lloyd Bird, John Birks, Mr and Mrs Blacklock, Don Blaxell, Jim Bourner, John Copyright © 2013 in text: John Wrigley Briggs, Colin Broadfoot, Dot Brown, the late George Brown, Ray Brown, Leslie Conway, Copyright © 2013 in map: Ian Faulkner Copyright © 2013 in photographs and illustrations: Murray Fagg Russell and Sharon Costin, Kirsten Cowley, Lyn Craven (Petraeomyrtus punicea photograph) Copyright © 2013 New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Richard Cummings, Bert -

Plant Charts for Native to the West Booklet

26 Pohutukawa • Oi exposed coastal ecosystem KEY ♥ Nurse plant ■ Main component ✤ rare ✖ toxic to toddlers coastal sites For restoration, in this habitat: ••• plant liberally •• plant generally • plant sparingly Recommended planting sites Back Boggy Escarp- Sharp Steep Valley Broad Gentle Alluvial Dunes Area ment Ridge Slope Bottom Ridge Slope Flat/Tce Medium trees Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire ✤ ■ •• Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka ✖■ •••• Kunzea ericoides kanuka ♥■ •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Metrosideros excelsa pohutukawa ♥■ ••••• • •• •• Small trees, large shrubs Coprosma lucida shining karamu ♥ ■ •• ••• ••• •• •• Coprosma macrocarpa coastal karamu ♥ ■ •• •• •• •••• Coprosma robusta karamu ♥ ■ •••••• Cordyline australis ti kouka, cabbage tree ♥ ■ • •• •• • •• •••• Dodonaea viscosa akeake ■ •••• Entelea arborescens whau ♥ ■ ••••• Geniostoma rupestre hangehange ♥■ •• • •• •• •• •• •• Leptospermum scoparium manuka ♥■ •• •• • ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Leucopogon fasciculatus mingimingi • •• ••• ••• • •• •• • Macropiper excelsum kawakawa ♥■ •••• •••• ••• Melicope ternata wharangi ■ •••••• Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe • ••• •• • •• ••• Myoporum laetum ngaio ✖ ■ •••••• Olearia furfuracea akepiro • ••• ••• •• •• Pittosporum crassifolium karo ■ •• •••• ••• Pittosporum ellipticum •• •• Pseudopanax lessonii houpara ■ ecosystem one •••••• Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ■ • •• • •• Sophora fulvida west coast kowhai ✖■ •• •• Shrubs and flax-like plants Coprosma crassifolia stiff-stemmed coprosma ♥■ •• ••••• Coprosma repens taupata ♥ ■ •• •••• •• -

The General Status of Alberta Wild Species 2000 | I Preface

Pub No. I/023 ISBN No. 0-7785-1794-2 (Printed Edition) ISBN No. 0-7785-1821-3 (On-line Edition) For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our website at www.gov.ab.ca/env/fw/status/index.html (available on-line Fall 2001) Front Cover Photo Credits: OSTRICH FERN - Carroll Perkins | NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG - Wayne Lynch | NORTHERN SAW-WHET OWL - Gordon Court | YELLOW LADY’S-SLIPPER - Wayne Lynch | BRONZE COPPER - Carroll Perkins | AMERICAN BISON - Gordon Court | WESTERN PAINTED TURTLE - Gordon Court | NORTHERN PIKE - Wayne Lynch ASPEN | gordon court prefacepreface Alberta has long enjoyed the legacy of abundant wild species. These same species are important environmental indicators. Their populations reflect the health and diversity of the environment. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development The preparation and distribution of this report is has designated as one of its core business designed to achieve four objectives: goals the promotion of fish and wildlife conservation. The status of wild species is 1. To provide information on, and raise one of the performance measures against awareness of, the current status of wild which the department determines the species in Alberta; effectiveness of its policies and service 2. To stimulate broad public input in more delivery. clearly defining the status of individual Central to achieving this goal is the accurate species; determination of the general status of wild 3. -

Tocopherols and Fatty Acid Profile in Baru Nuts (Dipteryx Alata Vog.), Raw and Roasted: Important Sources in Nature That Can Prevent Diseases

Food Science and Nutrition Technology ISSN: 2574-2701 Tocopherols and Fatty Acid Profile in Baru Nuts (Dipteryx Alata Vog.), Raw and Roasted: Important Sources in Nature that Can Prevent Diseases 1,3* 2 3 3 Lemos MRB , Zambiazi RC , de Almeida EMS and de Alencar ER Research Article Volume 1 Issue 2 1University of Brasilia, UnB, Brazil Received Date: July 11, 2016 2Federal University of Pelotas, UFPel, Brazil Published Date: July 25, 2016 3University of Brasilia, UnB-Brazil *Corresponding author: Miriam Rejane Bonilla Lemos (First author), Health Sciences Post graduation Program, Health Sciences Faculty, University of Brasília, Brasília, DF, PO Box 70910900, Brazil– PGCS-FS, University Campus Darcy Ribeiro- North wing, Zip code: 70.910.900 – Brasília-DF/Brazil, E-mail: [email protected] . Abstract Brazil has extensive biodiversity in their biomes, where the Cerrado, vegetation of the Brazilian interior, contributes a nutritional and medicinal potential still unexplored. The reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and secondary complications, which stand out with a higher incidence rate and prevalence on the world stage, have been positively associated with the consumption of fruits, vegetables and rich oil seeds of antioxidants. This protective potential is attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds that exert antioxidant activity, preventing risks to biological systems. Studies have shown that the constituents of plant foods have recognized ability to chelate divalent metals involved in the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which can prevent damage to the organism and the onset of diseases. Recent studies have shown that daily supplementation with Baru nuts [Dipteryx alata Vog.] reduced oxidative stress induced by iron in rats protecting biological systems from the harmful effects of free radicals. -

Conventional and Genetic Measures of Seed Dispersal for Dipteryx Panamensis (Fabaceae) in Continuous and Fragmented Costa Rican Rain Forest

Journal of Tropical Ecology (2007) 23:635–642. Copyright © 2007 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0266467407004488 Printed in the United Kingdom Conventional and genetic measures of seed dispersal for Dipteryx panamensis (Fabaceae) in continuous and fragmented Costa Rican rain forest Thor Hanson∗1, Steven Brunsfeld∗, Bryan Finegan† and Lisette Waits∗ ∗ Department of Forest Resources, University of Idaho, P.O. Box 441133, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1133, USA † Departamento Recursos Naturales y Ambiente, Centro Agronomico´ Tropical de Investigacion´ y Ensenanza˜ (CATIE), 7170 Turrialba, Costa Rica (Accepted 13 August 2007) Abstract: The effects of habitat fragmentation on seed dispersal can strongly influence the evolutionary potential of tropical forest plant communities. Few studies have combined traditional methods and molecular tools for the analysis of dispersal in fragmented landscapes. Here seed dispersal distances were documented for the tree Dipteryx panamensis in continuous forest and two forest fragments in Costa Rica, Central America. Distance matrices were calculated between adult trees (n = 283) and the locations of seeds (n = 3016) encountered along 100 × 4-m transects (n = 77). There was no significant difference in the density of seeds dispersed > 25 m from the nearest adult (n = 253) among sites. There was a strong correlation between the locations of dispersed seeds and the locations of overstorey palms favoured as bat feeding roosts in continuous forest and both fragments. Exact dispersal distances were determined for a subset of seeds (n = 14) from which maternal endocarp DNA could be extracted and matched to maternal trees using microsatellite analysis. Dispersal within fragments and from pasture trees into adjacent fragments was documented, at a maximum distance of 853 m.