THE CONCEPT of RIGHTS Law and Philosophy Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester Coro Gulbenkian Jonathan Nott Elena Zhidkova

Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester Coro Gulbenkian Jonathan Nott Elena Zhidkova 05 mar 2019 jonathan nott © guillaume megevand 05 MARÇO Ciclo Grandes TERÇA Intérpretes 20:00 — Grande Auditório Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester Coro Gulbenkian Coro Infanto-Juvenil da Universidade de Lisboa Jonathan Nott Maestro Elena Zhidkova Meio-Soprano Jorge Matta Maestro do Coro Gulbenkian Erica Mandillo Maestrina do Coro Infanto-Juvenil da UL Gustav Mahler Sinfonia n.º 3, em Ré menor Kräftig. Entschieden (Forte. Decisivo) Tempo di Menuetto Comodo. Scherzando Sehr langsam (Muito lento). Misterioso Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck (Alegre no tempo e atrevido na expressão) Langsam, Ruhevoll. Empfunden (Lento, tranquilo. Profundo) mecenas mecenas mecenas mecenas mecenas mecenas principal música e natureza estágios gulbenkian para orquestra concertos de domingo ciclo piano coro gulbenkian gulbenkian música Duração total prevista: c. 1h 45 min. Concerto sem intervalo 03 Kaliste, 7 de julho de 1860 Gustav Mahler Viena, 18 de maio de 1911 Sinfonia n.º 3, em Ré menor composição: 1896 estreia: Krefeld, 9 de junho de 1902 duração: c. 1h 45 min. Poucos foram os compositores que, de modo tão Começou por escrever aquele que é hoje o evidente quanto sinuoso, impregnaram a música segundo andamento, Tempo di Minuetto, tendo de si mesmos, num exercício onírico habitado apenas escrito o primeiro, Kräftig. Entschieden, por fantasmas, numa luta subconsciente entre no verão de 1896, depois de ter completado os a realidade, sublimada, e a fantasia, idealizada. restantes seis andamentos. Perante a totalidade Talvez seja este o motivo pelo qual não é da obra, Mahler mergulhou em cinco revisões evidente discorrer sobre a produção musical da sinfonia, acabando por dispensar o sétimo de Gustav Mahler. -

The Practice of Practice

The Practice of Practice by Jonathan Harnum Published independently by Sol Ut Press Find musician-friendly resources at www.Sol-Ut.com Copyright © 2014 by Sol Ut Press and Jonathan Harnum. All rights re- served. No part of this book may be copied or reproduced by any means without prior written permission of the publisher. Sol Ut and the Sol Ut logo are trademarks of Sol Ut Press. Sol Ut Press is committed to music education. Sol Ut Press has given away well over a million eBooks to music students all over the world. Get your own free digital copies of books on how to read music, jazz theory, and playing trumpet at www.sol-ut.com. Find free supporting material for this book at: www.ThePracticeOfPractice.com ISBN-13: 978-1456407971 ISBN-10: 145640797X Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Harnum, Jonathan. The Practice of practice / by Jonathan Harnum. p. cm. ISBN 978-14564079-7-1 Includes bibliographical references. 1. Practicing (Music). 2. Music --Performance --Psychological aspects. 3. Musical instruments --Instruction and study. 4. Music -- Instruction and study. I. Title. MT170 .H37 2014 781.44 --dc23 2014909342 FOR MICHELLE WITH SINCERE THANKS TO THESE GENEROUS MUSICIANS NICHOLAS BARRON ETHAN BENSDORF BOBBY BROOM AVISHAI COHEN SIDIKI DEMBELE HANS JøRGEN JENSEN INGRID JENSEN SONA JOBARTEH OM JOHARI RUPESH KOTECHA REX MARTIN CHAD MCCULLOUGH ERIN MCKEOWN ALLISON MILLER PETER MULVEY COLIN OLDBERG NICK PHILLIPS MICHAEL TAYLOR PRASAD UPASANI SERGE VAN DER VOO STEPHANE WREMBEL CONTENTS PART 1: WHAT’S GOIN’ ON? 1: THE CHICKEN OR THE EMBRYO ............................................ 3 2: SPINNING WHEEL, GOT TO GO ROUND ............................. -

Judicial Supremacy and the Modest Constitution

Judicial Supremacy and the Modest Constitution Frederick Schauert INTRODUCTION Judicial supremacy is under attack. From various points on the politi- cal spectrum, political actors as well as academics have challenged the idea that the courts in general, and the Supreme Court in particular, have a spe- cial and preeminent responsibility in interpreting and enforcing the Constitution. Reminding us that treating Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution as supreme and authoritative has no grounding in constitu- tional text and not much more in constitutional history, these critics seek to relocate the prime source of interpretive guidance. The courts have an important role to play, these critics acknowledge, but it is a role neither greater than that played by other branches, nor greater than the role to be played by "the people themselves."' The critics' understanding of a more limited function for the judiciary in constitutional interpretation appears to rest, however, primarily on a highly contestable conception of the point of having a written constitution in the first place. According to this conception, a constitution, and espe- cially the Constitution of the United States, is the vehicle by which a de- mocratic polity develops its own fundamental values. A constitution, therefore, becomes both a statement of our most important values and the vehicle through which these values are created and crystallized. Under this conception of the role of a written constitution, it would indeed be a mis- take to believe that the courts should have the preeminent responsibility for interpreting that constitution. For this task of value generation to devolve Copyright © 2004 California Law Review, Inc. -

Potential of Three Microbial Bio-Effectors to Promote Maize Growth and Nutrient Acquisition from Alternative Phosphorous Fertilizers in Contrasting Soils

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Copenhagen University Research Information System Potential of three microbial bio-effectors to promote maize growth and nutrient acquisition from alternative phosphorous fertilizers in contrasting soils Thonar, Cécile; Lekfeldt, Jonas Duus Stevens; Cozzolino, Vincenza; Kundel, Dominika; Kulhánek, Martin; Mosimann, Carla; Neumann, Günter; Piccolo, Alessandro; Rex, Martin; Symanczik, Sarah; Walder, Florian; Weinmann, Markus; de Neergaard, Andreas; Mäder, Paul Published in: Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture DOI: 10.1186/s40538-017-0088-6 Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Thonar, C., Lekfeldt, J. D. S., Cozzolino, V., Kundel, D., Kulhánek, M., Mosimann, C., ... Mäder, P. (2017). Potential of three microbial bio-effectors to promote maize growth and nutrient acquisition from alternative phosphorous fertilizers in contrasting soils. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 4(1), [7]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-017-0088-6 Download date: 08. apr.. 2020 Thonar et al. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. (2017) 4:7 DOI 10.1186/s40538-017-0088-6 RESEARCH Open Access Potential of three microbial bio‑effectors to promote maize growth and nutrient acquisition from alternative phosphorous fertilizers in contrasting soils Cécile Thonar1* , Jonas Duus Stevens Lekfeldt2, Vincenza Cozzolino3, Dominika Kundel1, Martin Kulhánek4, Carla Mosimann1,5, Günter Neumann6, Alessandro Piccolo3, Martin Rex7, Sarah Symanczik1, Florian Walder1,8, Markus Weinmann6, Andreas de Neergaard2 and Paul Mäder1 Abstract Background: Agricultural production is challenged by the limitation of non-renewable resources. Alternative fertiliz- ers are promoted but they often have a lower availability of key macronutrients, especially phosphorus (P). -

River Weekly News Read Online: LORKEN Publications, Inc

Weather and Tides FREE page 29 Take Me Home VOL. 20, NO. 2 From the Beaches to the River District downtown Fort Myers JANUARY 8. 2021 Learn about life in space photos provided Explore stars and nebulas Out Of This World it is about the creativity and excitement of air travel and spaceflight reimagined at the IMAG. Experience At The IMAG is planning several Inspiration Hubble Space Telescope over planet Earth Takes Flight programs, exhibits and additional planned specials also include the robots move and what they can do, and Science Center events, displays and hands-on activities introduction of the IMAG Junior Astronaut find out about life support in outer space. he IMAG History & Science Center for guests, families and members as well Training Program and the IMAG Frequent Guests can try out their skills for is featuring Inspiration Takes Flight, as homeschool students and scouts that Flyer Plan. Visit wwwtheimag.org for more liftoff, flying and landing a space craft on Tcelebrating the history and science feature Science on a Sphere shows, details and launch dates. the moon, Mars or Jupiter in astronaut of flight while honoring the achievements IMAG LIVE science shows, IMAG Science Visitors can explore stars and nebulas, training simulators. Also, test your talents of aviators, astronauts and aerospace Saturdays, workshops and mini-workshops exoplanets and galaxies, and other cosmic to maneuver a rover on the rocky crater engineers as well the successes of pioneers, and a special Member Night. As part of wonders. Learn about rockets and robots, surface of a planet. pilots and people inspired to take flight and Inspiration Takes Flight, the IMAG is also planets and planes. -

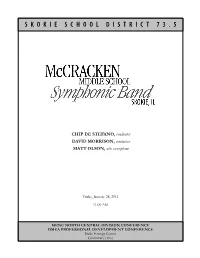

Concert Program

SKOKIE SCHOOL DISTRICT 73.5 CHIP DE STEFANO, conductor DAVID MORRISON, conductor MATT OLSON, alto saxophone Friday, January 28, 2011 11:00 AM MENC NORTH CENTRAL DIVISION CONFERENCE OMEA PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE Duke Energy Center Cincinnati, Ohio CHIP DE STEFANO, CONDUCTOR CONCERT PROGRAM FRIDAY, JANUARY 28, 2011 • 11:00 AM DUKE ENERGY CENTER • JUNIOR BALLROOM UNRAVELING ANDREW BOYSEN, JR. A SIMPLE SONG LEONARD BERNSTEIN ARRANGED BY MICHAEL SWEENEY FANTASY ON AMERICAN SAILING SONGS CLARE GRUNDMAN David Morrison, conductor MASS FROM “LA FIESTA MEXICANA” H. OWEN REED Matt Olson, saxophone DIVERSION FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND BAND BERNHARD HEIDEN FOUNDRY JOHN MACKEY MEN OF OHIO HENRY FILLMORE MCCRACKEN MIDDLE SCHOOL SYMPHONIC BAND FLUTE BASS CLARINET TROMBONE Silvia Burian 8 Darrien Min 8 David Fernandez-Wang 6 Samantha dela Cruz 8 Tenzin Wangdak 7 Aaron Humphries-Dolnick 8 Karli Goldenberg 8 Aaron Niederman 7* Matthew Harris-Ridker 8 ALTO SAXOPHONE Mark Wilson 8 Anna Hill 7 Oscar Benbow 6 Martin Wiviott 7 Myhanh Lu 7 Amanda Ly 8 Erin Martin 7 Sean Riordan 8 EUPHONIUM Natalie Niederman 7 Conor Toledo 7 Luc Walkington 8* Alexis Schlau 7 Brendan Ward 6 Milan Woody 8 TENOR SAXOPHONE Carissa Yau 8 Lyka Ando 8 TUBA Rose Zubeck 7 Yuji Tsukamoto 7 Elizabeth Akinboboye 7 Matthew Ginsburg 8 OBOE BARITONE SAXOPHONE Lucy Chavez 7 Josh Bynum 8 PERCUSSION Jennifer Goodfriend 7 Aaliyah Williams 8 Vanessa Elias 6* Andrew Goldberg 8 CLARINET CORNET Courtney Goldenberg 6 Daniel Aisenberg 7* Ari Bearman 7 Jordan Greenfield 6 Ben Barov 7 Amy Burke 7 Alexis Moy 5* Neil Ducklow 7 Brian DeVilla 8 Daniel Sahyouni 8 Cree Glanz 8 Carolyn Dwyer 7* Juliana Tichota 6 Amanda Green 8 Chris Scheithauer 7 Sarah Ly 7* Daniel Vargas 6 Angela Martin 6 Adam Yusen 8 Nina Yonan 7 Isabelle Zubeck 6 FRENCH HORN * additional percussion on Foundry Alyssa Moy 7 Sophie Steger 7 MCCRACKEN MIDDLE SCHOOL BAND PROGRAM SKOKIE, ILLINOIS The Village of Skokie is located just 16 miles northwest of downtown Chicago. -

Guest Artist Recital: Rex Martin Rex Martin, Tuba

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-16-2012 Guest Artist Recital: Rex Martin Rex Martin, Tuba Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Martin,, Rex Tuba, "Guest Artist Recital: Rex Martin" (2012). School of Music Programs. 635. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/635 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Upcoming Events College of Fine Arts School of Music Tuesday - 17, April 2012 Convocation Hour 11:00 AM CPA * Faculty String Quartet 7:30 PM KRH * Wednesday - 18, April 2012 Andrew François, viola 6:00 PM KRH * Piano Project 8:00 PM KRH * Guest Artist Recital Series Thursday - 19, April 2012 Music Factory Concert 8:00 PM KRH * Friday - 20, April 2012 Matt Brusca, percussion 6:00 PM KRH * Rex Martin, Tuba Jazz Ensemble I & II 8:00 PM CPA Sunday - 22, April 2012 Yoko Yamada, Piano Guest Artist Master Class, Noon KRH * Kenneth Tse, saxophone Symphonic Winds Concert 3:00 PM CPA Guest Artist Recital Kenneth Tse, saxophone 5:00 PM KRH * Brooke Davis, collaborative piano 8:00 PM KRH * Monday - 23, April 2012 Nick DiSalvio, saxophone 6:00 PM KRH * Chamber Winds 8:00 PM KRH * Tuesday - 24, April 2012 Student String Chamber Concert 7:30 PM KRH * Wednesday - 25, April 2012 Gillian Borth, viola 6:00 PM KRH * Guitar Studio 7:30 PM KRH * Symphonic Band and University Band 8:00 PM CPA Kemp Recital Hall April 16, 2012 Monday Evening 8:00 p.m. -

The Problematic Legacy of Cardozo

Oregon Law Review Winter 2000 - Volume 79, Number 4 (Cite as: 79 Or. L. Rev. 1033) DAN SIMON* The Double-Consciousness of Judging: The Problematic Legacy of Cardozo Copyright © 2000, University of Oregon; Dan Simon INTRODUCTION There is a growing awareness in legal scholarship that a crisis of sorts pervades the legal field. In the now famous The Lost Lawyer, Dean Anthony Kronman has identified an adverse transformation of the character of the legal profession. n1 Professor Mary Anne Glendon has put forth a critique of the rights-based rhetoric that predominates legal discourse. n2 Professor Steven Smith has both broadened and deepened these discouraging observations by suggesting that the legal community is suffering from a crisis of faith. As Smith astutely points out, there is a fundamental problem with the integrity of legal discourse in that legal actors operate in a state of discordance between their beliefs and practices. Participants in this discourse have come to take for granted that the reasons they present in support of their positions are quite distinct from the "real reasons" that underlie [*1034] them. n3 Smith coined this duplicity a "schizophrenic condition," suggesting that it is a "sign of something deeply wrong in modern legal thought." n4 This paper explores the possibility that judicial reasoning might be one of the causes of this state of duplicity. This proposition is explored through an analysis of the work of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, an exemplary and distinguished inhabitant of the American judicial pantheon. I will briefly review recent scholarship that champions his legacy as the product of renaissance-like qualities: encompassing brilliant judicial performance and insightful writing about judging. -

Viewpoint Discrimination Marjorie Heins

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 24 Article 3 Number 1 Fall 1996 1-1-1996 Viewpoint Discrimination Marjorie Heins Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Marjorie Heins, Viewpoint Discrimination, 24 Hastings Const. L.Q. 99 (1996). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol24/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Viewpoint Discrimination By MARJORIE HEINS* Table of Contents I. The Semantics of Suppression .......................... 105 A. Viewpoint Neutrality ................................ 105 B. Rules About Content ............................... 110 C. Political, Controversial, and Religious Speech ...... 115 II. Sex, Vulgarity, and Offensiveness ....................... 122 m. Government Benefits and Property ..................... 136 IV. Government Speech .................................... 150 V. Public Education: The Pico Paradox .................... 159 Conclusion ..................................................... 168 Introduction "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in poli- tics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein."1 With these words, Jus- * Director, American Civil Liberties Union Arts Censorship Project; Senior Staff Counsel, ACLU Legal Department; J.D., Harvard University, 1978; author, SEx, SIN, AND BLASPHEMY: A GuIDE TO AMERICA'S CENSORSHIP WARS (1993). The author participated in several of the cases or controversies mentioned in this Article. -

The First Amendment As Ideology

William & Mary Law Review Volume 33 (1991-1992) Issue 3 Article 5 March 1992 The First Amendment as Ideology Frederick Shauer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Frederick Shauer, The First Amendment as Ideology, 33 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 853 (1992), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol33/iss3/5 Copyright c 1992 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE FIRST AMENDMENT AS IDEOLOGY FREDERICK SCHAUER* Not surprisingly, Learned Hand said it best. Writing for the Second Circuit in InternationalBrotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 501 v. NLRB, 1 he captured beautifully the paradox I wish to explore here: The interest, which [the First Amendment] guards, and which gives it its importance, presupposes- that there are no ortho- doxies-religious, political, economic, or scientific-which are immune from debate and dispute. Back of that is the assump- tion-itself an orthodoxy, and the one permissible exception- that truth will be most likely to emerge, if no limitations are imposed upon utterances that can with any plausibility be regarded as efforts to present grounds for accepting or reject- 2 ing propositions whose truth the utterer asserts, or denies. I want to focus not on Hand's restatement of the standard marketplace-of-ideas principle that the value of freedom of speech lies in its instrumental value in (probabilistically) increasing the likelihood of identifying truth and rejecting falsehood. -

REX MARTIN, Professor of Philosophy

REX MARTIN, Department of Philosophy The University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7590 USA dept. phone: (785) 864-3976 or (785) 864-2334 fax: (785) 864-4298, home phone: (913) 236-4084 INTERNET E-mail address: [email protected] or [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Education Ph.D. Columbia University, 1967, in philosophy M.A. Columbia University, 1960, in philosophy B.A. Rice University, 1957, "with honors in History" Post-Graduate study, University of Edinburgh (Scotland), 1965-66, in theology and philosophy Positions University of Kansas, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, 1968-70, Associate Professor, 1970-73, Professor, 1973-2009, Professor Emeritus, 2009- , Chair, 1972-78 Lycoming College (Pa.), Assistant Professor of Philosophy, 1966-68 Purdue University, Instructor in Political Science, 1962-65 Columbia University, Lecturer in Philosophy, 1961-62 Visiting (V) or Joint (J) Teaching Appointments University of Helsinki (Finland), Professor of Moral and Social Philosophy, 14 April - 13 May 2000 (V) University of Wales Swansea (U.K.), Professor of Political Theory and Government, Department of Politics, Spring Semesters 1995-2000 (J) University of Sydney (Australia), Professor of Jurisprudence, Faculty of Law, Second Semester 1992 (V) University of Auckland (New Zealand), Professor of Philosophy, middle term, July 1-August 15, 1981 (V) Mount Vernon College (D.C.), Washington Summer Program, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Summer 1965 (V) Honors and Awards Visiting Fellow, -

ARISTOTLE and the CONCEPT of LAW John T. Valauri

VALAURI_GALLEYS 5/10/2011 10:10:34 AM DIALECTICAL JURISPRUDENCE: ARISTOTLE AND THE CONCEPT OF LAW John T. Valauri* General theories of law struggle to do justice to the multiple dualities of the law.1 INTRODUCTION Western law, culture, and philosophy thought that they were say- ing goodbye to Aristotle as they entered into modernity, only now to find the ancient philosopher standing in wait as they leave mod- ernity and enter into post-modernity. But what use do we have for Aristotle at this time? He can perform a valuable service for us—he offers a therapy for the “bipolar disorder”2 in contemporary juris- prudence and philosophy.3 This disorder is manifested in the wide- spread tendency to approach and analyze philosophical topics as dueling dichotomies, incapable of resolution or reconciliation. It is all too often assumed at the outset that one is faced with a stark ei- ther/or sort of choice between alternatives, so participants in the philosophical debates arising out of this approach typically take one side of the dichotomy and see it as their task to marginalize and di- minish the other side of the dichotomy.4 H.L.A. Hart diagnosed one case of this disorder in his famous depiction of American jurispru- dence as torn between the noble dream that judges can always *- Professor of Law, Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University. B.A., 1972; J.D., 1975, Harvard. 1. JOSEPH RAZ, BETWEEN AUTHORITY AND INTERPRETATION 1 (2009). 2. In this Article, I will use the notion of a “bipolar disorder” in philosophy in a broader way to refer to a more general dichotomy problem common today in approaches to philoso- phical topics.