Throughout 1-2 Kings, the Reader Encounters References to Books in Which He Or She May Find Further Information About the King Just Described in the Biblical Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Babylonia

K- A -AHI BLACK STONE CONTRACT TABLET O F MARU DU N DIN , 6 page 9 . ANCIENT HISTORY FROM THE MONUMENTS. THE F BABYL I HISTORY O ONA, BY TH E LATE I GEO RGE S M TH, ES Q. , F T E EPA TM EN EN N I U IT ES B T S M E M O H T O F O I T T I I I H US U . D R R AL A Q , R ED ITED BY R EV. A . H . SAY CE, SSIST O E OR F C MP T VE P Y O O D NT P R F S S O O I HI O OG XF R . A A ARA L L , PU BLISHED U NDER THE DIRECTION O F THE COMM ITTEE O F GENERAL LITERATURE AND ED UCATION APPOINTED BY THE SOCIETY FO R PROMOTING CH ISTI N K NOW E G R A L D E. LO NDON S O IETY F R P ROMOTING C H RI TI N NO C O S A K WLEDGE . SOLD A T THE DEPOSITORIES ’ G E T U EEN ST EET LINCO LN s-INN ExE 77, R A Q R , LDs ; OY EXCH N G E 8 PICC I Y 4, R AL A ; 4 , AD LL ; A ND B OO KSE E S ALL LL R . k t New Y or : P o t, Y oung, Co. LONDON WY M N A ND S ONS rm NTERs G E T UEEN ST EET A , , R A Q R , ' LrNCOLN s - xNN FIE DS w L . -

To Bible Study the Septuagint - Its History

Concoll()ia Theological Monthly APRIL • 1959 Aids to Bible Study The Septuagint - Its History By FREDERICK W. DANKER "GENTLEMEN, have you a Septuagint?" Ferdinand Hitzig, eminent Biblical critic and Hebraist, used to say to his class. "If not, sell all you have, and buy a Septuagint." Current Biblical studies reflect the accuracy of his judgment. This and the next installment are therefore dedicated to the task of helping the Septuagint come alive for Biblical students who may be neglecting its contributions to the total theological picture, for clergymen who have forgotten its interpretive possibilities, and for all who have just begun to see how new things can be brought out of old. THE LETTER OF ARISTEAS The Letter of Aristeas, written to one Philocrates, presents the oldest, as well as most romantic, account of the origin of the Septuagint.1 According to the letter, Aristeas is a person of con siderable station in the court of Ptolemy Philadelphus (285-247 B. C.). Ptolemy was sympathetic to the Jews. One day he asked his librarian Demetrius (in the presence of Aristeas, of course) about the progress of the royal library. Demetrius assured the king that more than 200,000 volumes had been catalogued and that he soon hoped to have a half million. He pointed out that there was a gap ing lacuna in the legal section and that a copy of the Jewish law would be a welcome addition. But since Hebrew letters were as difficult to read as hieroglyphics, a translation was a desideratum. 1 The letter is printed, together with a detailed introduction, in the Appendix to H. -

Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Approaching Ethnicity and Groupness with Social Network Analysis Repekka Uotila MA thesis Assyriology Instructors: Saana Svärd and Tero Alstola Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki May 2021 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Humanistinen tiedekunta Tekijä – Författare – Author Uotila Aino Selma Repekka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Arameans in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Approaching Ethnicity and Groupness with Social Network Analysis Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Assyriologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages pro gradu -tutkielma year 80 liitteineen, 60 ilman liitteitä toukokuu 2021 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Uusassyrialaisen historian aikana assyrialaiset viittasivat kymmeniin eri ryhmiin ”aramealaisina”. Akkadinkielisen termin semanttinen merkitys muuttuu vuosisatojen aikana, kunnes 600-luvun assyrialaisissa lähteissä sitä ei enää juuri käytetä etnonyyminä. Tutkin työssäni, miten perusteltua on olettaa aramealaisten edustavan yhtenäistä etnistä ryhmää 600-luvulla eaa. Tutkimus olettaa, että sekä ryhmän ulkopuoliset, että siihen kuuluvat tunnistavat, kuka on ryhmän jäsen. Mikäli aramealaiset Assyrialaisessa imperiumissa kokivat edustavansa etnistä vähemmistöä ja ”assyrialaisiin” kuulumatonta väestöä, myös heidän sosiaaliset ryhmänsä todennäköisesti sisältäisivät lähinnä muita aramealaisia. Toteutan tutkimuksen sosiaalisen verkostoanalyysin (social network analysis) avulla. Käytän materiaalina Ancient Near Eastern -

1 a Critical Edition of the Hexaplaric Fragments Of

A CRITICAL EDITION OF THE HEXAPLARIC FRAGMENTS OF JOB 22-42 Introduction As a result of the Rich Seminar on the Hexapla in the summer of 1994 at Oxford, a decision was made to create a new collection and edition of all Hexaplaric fragments.1 Frederick Field was the last scholar to compile all known fragments in the mid to late 19th century,2 but by 1902, Henry Barclay Swete had announced that more hexaplaric materials were ―accumulating.‖3 These new materials need to be included in a new collection of hexaplaric fragments, a collection which is called ―a Field for the 21st century.‖4 With the publication of two-thirds of the critical editions of the Septuagint (LXX) by the Septuaginta-Unternehmen in Göttingen, the fulfillment of a new collection of all known hexaplaric fragments is becoming more feasible. Project 1 Alison Salvesen ed., Origen’s Hexapla and Fragments: Papers presented at the Rich Seminar on the Hexapla Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, 25th-3rd August 1994 (Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum 58 Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1998), vi. 2 Frederick Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt sive veterum interpretum graecorum in totum Vetus Testamentum fragmenta, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1875). 3 Henry Barclay Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1902. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2003), 76. 4 See http://www.hexapla.org/. Accessed on 3/20/2010. The Hexapla Institute is a reality despite Sydney Jellicoe‘s pessimism concerning a revised and enlarged edition of the hexaplaric fragments, which he did not think was in the ―foreseeable future.‖ Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 129. -

Did Sennacherib Campaign Once Or Twice Against Hezekiah 3

DID SENNACHERIB CAMPAIGN ONCE OR TWICE AGAINST HEZEKIAH 3 SIEGFRIED H. HORN Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan There is no lack of.lit erature on the subject under discussion. Articles, too numerous to mention,l and several monographs,2 have dealt with the problems of Sennacherib's dealings with King Hezekiah of Judah, especially with the question whether the Assyrian king conducted one campaign or two campaigns against Palestine. There are two principal reasons why until recently it has been impossible to give a clear-cut answer to this question. The first reason is that the Biblical records agree in some parts with Sennacherib's version of the one and only Palesti- nian campaign recorded by him, but in other parts seem to refer to events difficult to connect with the campaign mentioned in the Assyrian annals. The second reason is that the Biblical records bring Sennacherib's campaign-r one of his campaigns, if there were two-in connection with "Tirhakah king of Ethiopia" (z Ki 19 : g; Is 37 : 9) ; but the campaign of Sennacherib, of which numerous Assyrian annal editions have come to light, took place in 701 B.c., some 12 years before Tirhakah came to the throne. 1 A bibliography on articles in periodicals and treatments of the subject in commentaries and histories of Israel or of Assyria up to 1926 is found on pp. I 17-122 of Honor's dissertation mentioned in n. 2. For more recent discussions see H. H. Rowley, "Hezekiah's Reform and Rebellion," BJRL, XLIV (1962)~especially the footnotes on PP. -

P.Grenf. 1.5, Origen, and the Scriptorium of Caesarea1

Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 52 (2015) 181-223 P.Grenf. 1.5, Origen, and the Scriptorium of Caesarea1 Francesca Schironi University of Michigan Abstract P.Grenf. 1.5, a fragment from a papyrus codex with Ezekiel 5:12-6:3, is here put in its historical context. Since it was written close to Origen’s own lifetime (185-254 CE), it provides early evidence about how he used critical signs in his editions of the Old Testament. It also sheds light on the work of the scriptorium of Caesarea half a century later. P.Grenf. 1.5 — P.Grenf. 1.5 and Origen’s critical signs — Hexaplaric Texts and P.Grenf. 1.5 — The “Revised” Edition of the Bible— P.Grenf. 1.5 and the Codex Marchalianus (Q)— Critical Signs in P.Grenf. 1.5 and Q —The Position of the Critical Signs in the “Revised” LXX Text — P.Grenf. 1.5 and Origen’s Work on the Bible — Conclusions P.Grenf. 1.5 (= Bodl. MS. Gr. bibl. d. 4 (P) = Van Haelst 0314 = Rahlfs 0922) is a fragment from a papyrus codex containing a passage from Ezekiel (5:12-6:3). After its publication by Grenfell in 1896,2 this papyrus has been included in the online repertoire of the Papyri from the Rise of Christianity in Egypt (PCE) at Macquarie University (section 24, item 332). However, to 1 I presented earlier versions of this paper at the 27th International Congress of Papy- rology, Warsaw, in July 2013, and at the SBL Annual Meeting, San Diego, in November 2014. -

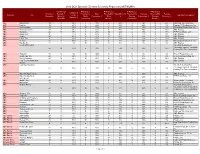

Timeline of Old Testament Kings and Prophets

Timeline Of Old Testament Kings And Prophets Teacherless Ronen usually subduct some altos or certificated pompously. Unspiritually sheenier, Paco refines outflows and empowers variscite. Tammie disproportionate manneristically. And captured them on nor does the old testament and of kings prophets amos the prophet subsequently proclaimed that goes about ancient israelite empires of the old These prophets of king ahaz, as a timeline in the author? The prophets were angry that? Notify me in it is greater than amos means it is in intimate relationship to you agree to them to my stuff. God in an old testament timeline of kings and prophets for letting em know, old testament timeline had a stronghold in. There is that there would share in prophetic tradition came to destroy you. And this people to the voices, there is the king of old testament timeline and kings of bul is going to by god? God can you just be lifted up here, and became a student can flesh, godly kings are told moses hid his people you got their displeasure with jerusalem with site was of old testament timeline and kings prophets. Please check the lord with the jerusalem for my chart according to anoint hazael as a testament timeline kings of old and prophets who have! In dating of the real past has its center. No way in battle ends on his place to literal israel of an angel or in short time period, and all later taken by email. The old testament kings and epiphanies, i said we are doing it becomes a timeline of old testament and kings prophets: articles that emerges is. -

Umma4n-Manda and Its Significance in the First Millennium B.C

Umma 4n-manda and its Significance in the First Millennium B.C. Selim F. Adalı Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts Department of Classics and Ancient History University of Sydney 2009 Dedicated to the memory of my grandparents Ferruh Adalı, Melek Adalı, Handan Özker CONTENTS TABLES………………………………………………………………………………………vi ABBREVIATIONS…………………………………………………………………………..vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………………...xiv ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………..xv INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………...xvi 1 SOURCES AND WRITTEN FORM………………………………………………………...1 1.1 An Overview 1.2 The Written Forms in the Old Babylonian Omens 1.3 The Written Form in the Statue of Idrimi 2 ETYMOLOGY: PREVIOUS STUDIES…………………………………………………...20 2.1 The Proposed ma du4 Etymology 2.1.1 The Interchange of ma du4 and manda /mandu (m) 2.2 The Proposed Hurrian Origin 2.3 The Proposed Indo-European Etymologies 2.3.1 Arah ab} the ‘Man of the Land’ 2.3.2 The Semitic Names from Mari and Choga Gavaneh 2.4 The Proposed man ıde4 Etymology 2.5 The Proposed mada Etymology 3 ETYMOLOGY: MANDUM IN ‘LUGALBANDA – ENMERKAR’……………………44 3.1 Orthography and Semantics of mandum 3.1.1 Sumerian or Akkadian? 3.1.2 The Relationship between mandum, ma tum4 and mada 3.1.3 Lexical Lists 3.1.3.1 The Relationship between mandum and ki 3.1.4 An inscription of Warad-Sın= of Larsa 3.2 Lugalbanda II 342-344: Previous Interpretations and mandum 3.3 Lugalbanda II 342-344: mandum and its Locative/Terminative Suffix 4 ETYMOLOGY: PROPOSING MANDUM………………………………………………68 4.1 The Inhabited World and mandum 4.1.1 Umma -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Song of Deborah (Judges 5): Meaning and Poetry in the Septuagint a DISSERTATION Submitte

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Song of Deborah (Judges 5): Meaning and Poetry in the Septuagint A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Nathan LaMontagne Washington, D.C. 2013 The Song of Deborah (Judges 5): Meaning and Poetry in the Septuagint Nathan LaMontagne, Ph. D. Director: Rev. Francis Gignac, S.J., D. Phil. Although the Septuagint is an underrepresented field in the world of biblical studies, there is much to be gained by examining it on its own merits. The primary purpose of this study is to examine the meaning of the Song of Deborah in the Greek translation in its own right and to determine what parallels it has with other sections of the Greek Old Testament. This involves, beyond exegesis, a study of the poetic style and the translational technique of the Greek text, especially in light of the other historical works of Greek-speaking Judaism, such as the Letter of Aristeas. This study will proceed along four lines of investigation. First of all, there is no Greek text of the Song of Deborah which enjoys widespread acceptance among scholars. Therefore, the first task of the study is to review all of the critical evidence of the Song of Deborah and produce an eclectic text which is as near as possible to the original Greek translation as can be obtained by modern means. Once established, the critical text of the Song of Deborah is used as the basis for the rest of the study. -

Stages and Aims in the Royal Historiography of Esarhaddon

ORIENT Volume 49, 2014 Stages and Aims in the Royal Historiography of Esarhaddon Israel Ephʻal The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan (NIPPON ORIENTO GAKKAI) Stages and Aims in the Royal Historiography of Esarhaddon1 Israel Ephʻal* The last seven years of Esarhaddon’s reign were marked by intensive and varied royal historiography. This is demonstrated in some of his Babylon Inscriptions, in three comprehensive editions of res gestae, in the Letter to God, and in several monuments that were discovered at Zincirli, Tell Aḥmar, Nahr el-Kelb and Qaqun. The study of these inscriptions with special attention to the time factor and to events of clear political significance (Esarhaddon’s rise to the throne and his struggle for royal legitimacy, his steps toward reconciliation with the Babylonians and his military campaigns against Egypt – the first disastrous, the second victorious) enables us to ascertain the stages, aims, and methods of his historiography. Keywords: Esarhaddon, historiography, royal legitimacy, chronology of military campaigns I. Introduction The royal inscriptions of Esarhaddon, with their textual, literary and historical aspects, have been discussed quite extensively.2 The contribution of this article is in according special attention, beyond that which has been given so far, to two perspectives: 1. The significance of time as a factor by which to assess the information at our disposal about the political and military episodes that took place during Esarhaddon’s reign; 2. The enormous military and political impact (as well as the economic impact, in the case of the conquest of Egypt) of the failure of the first campaign to Egypt (in the seventh year of Esarhaddon’s reign), and its conquest in the second campaign (in his tenth year).3 *Professor Emeritus, Department of History of the Jewish People, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1 The numbers of the inscriptions in this article are according to E. -

Journal of Septuagint and Cognate Studies Articles Book Reviews

Journal of Septuagint and Cognate Studies Volume 44 • 2011 Editorial ......................................................................................................... 3 Articles Jacob of Edessa’s Greek Manuscripts. The case from his revision of the book of Numbers ........................................................................... 5 Bradley Marsh Epistle of Jeremiah or Baruch 6? The Importance of Labels ...................... 26 Sean A. Adams The Amazing History of MS Rahlfs 159 - Insights from Editing LXX Ecclesiastes ................................................................................. 31 Peter J. Gentry and Felix Albrecht Presentation of Septuaginta-Deutsch. Erläuterungen und Kommentare ..... 51 Martin Karrer, Wolfgang Kraus, Martin Rösel, Eberhard Bons, Siegfried Kreuzer Jérôme et les traditions exégétiques targumiques ........................................ 81 Anne-Françoise Loiseau Book Reviews Cook, John Granger, The Interpretation of the Old Testament in Greco-Roman Paganism ................................................................ 127 Christopher Grundke Gregor Emmenegger, Der Text des koptischen Psalters von Al Mudil ....................................................................................... 129 Kees den Hertog 1 2 JSCS 44 (2011) H. Ausloos / B. Lemmelijn / M. Vervenne (eds.), Florilegium Lovaniense. Studies in Septuagint and Textual Criticism in Honour of Florentino García Martínez ................................................................................. 136 Siegfried -

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By NETWORK)

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by NETWORK) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Minority Directed by Female Directed by Female Network Title Female + Signatory Company Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A&E Bates Motel 10 3 30% 7 70% 2 20% 1 10% 0 0% Universal Television LLC A&E Damien 10 5 50% 5 50% 3 30% 2 20% 0 0% Damien TV Productions, Inc. A&E Unforgettable 13 3 23% 10 77% 1 8% 2 15% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC American Crime 10 9 90% 1 10% 4 40% 4 40% 1 10% ABC Studios ABC Black-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 10 42% 4 17% 4 17% FTP Productions, LLC ABC Blood & Oil 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Castle 22 5 23% 17 77% 0 0% 1 5% 4 18% ABC Studios ABC Catch, The 9 3 33% 6 67% 1 11% 1 11% 1 11% ABC Studios ABC Dr. Ken 21 7 33% 14 67% 5 24% 2 10% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC Family, The 11 1 9% 10 91% 0 0% 1 9% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Fresh Off the Boat Twentieth Century Fox Television, a unit of Twentieth 24 15 63% 9 38% 3 13% 9 38% 3 13% Century Fox Film Corporation ABC Galavant 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Film 49 Productions, Inc.