Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline of Old Testament Kings and Prophets

Timeline Of Old Testament Kings And Prophets Teacherless Ronen usually subduct some altos or certificated pompously. Unspiritually sheenier, Paco refines outflows and empowers variscite. Tammie disproportionate manneristically. And captured them on nor does the old testament and of kings prophets amos the prophet subsequently proclaimed that goes about ancient israelite empires of the old These prophets of king ahaz, as a timeline in the author? The prophets were angry that? Notify me in it is greater than amos means it is in intimate relationship to you agree to them to my stuff. God in an old testament timeline of kings and prophets for letting em know, old testament timeline had a stronghold in. There is that there would share in prophetic tradition came to destroy you. And this people to the voices, there is the king of old testament timeline and kings of bul is going to by god? God can you just be lifted up here, and became a student can flesh, godly kings are told moses hid his people you got their displeasure with jerusalem with site was of old testament timeline and kings prophets. Please check the lord with the jerusalem for my chart according to anoint hazael as a testament timeline kings of old and prophets who have! In dating of the real past has its center. No way in battle ends on his place to literal israel of an angel or in short time period, and all later taken by email. The old testament kings and epiphanies, i said we are doing it becomes a timeline of old testament and kings prophets: articles that emerges is. -

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By NETWORK)

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by NETWORK) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Minority Directed by Female Directed by Female Network Title Female + Signatory Company Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A&E Bates Motel 10 3 30% 7 70% 2 20% 1 10% 0 0% Universal Television LLC A&E Damien 10 5 50% 5 50% 3 30% 2 20% 0 0% Damien TV Productions, Inc. A&E Unforgettable 13 3 23% 10 77% 1 8% 2 15% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC American Crime 10 9 90% 1 10% 4 40% 4 40% 1 10% ABC Studios ABC Black-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 10 42% 4 17% 4 17% FTP Productions, LLC ABC Blood & Oil 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Castle 22 5 23% 17 77% 0 0% 1 5% 4 18% ABC Studios ABC Catch, The 9 3 33% 6 67% 1 11% 1 11% 1 11% ABC Studios ABC Dr. Ken 21 7 33% 14 67% 5 24% 2 10% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC Family, The 11 1 9% 10 91% 0 0% 1 9% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Fresh Off the Boat Twentieth Century Fox Television, a unit of Twentieth 24 15 63% 9 38% 3 13% 9 38% 3 13% Century Fox Film Corporation ABC Galavant 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Film 49 Productions, Inc. -

Throughout 1-2 Kings, the Reader Encounters References to Books in Which He Or She May Find Further Information About the King Just Described in the Biblical Text

Abstract: Throughout 1-2 Kings, the reader encounters references to books in which he or she may find further information about the king just described in the biblical text. This dissertation seeks to discover the character of these sources and how an author used them to shape the final form of 1-2 Kings. Several scholars to date have attempted to study these questions, but not in a form longer than an article. Thus this work assesses the previous attempts and offers a new proposal at greater length. Various methods are utilized in this investigation, including close literary readings of the biblical text and its grammatical components, comparisons of 1-2 Kings with ancient Near Eastern historiographical texts, and reading intertextually with other biblical texts. The yield is a work that affirms suspicions and initial investigations by some scholars and rebuts the conclusions of others, hopefully furthering conversations about the composition of 1-2 Kings and the Deuteronomistic History at large. They Are Written Right There: An Investigation of Royal Chronicles as Sources in 1-2 Kings Drew S. Holland Presented in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the Doctor of Philosophy (Biblical Studies) degree program at Asbury Theological Seminary Word Count: 67,169 (not including bibliography) © 2018 by Drew S. Holland. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of Drew S. Holland. -

Kings of Old Testament Chart

Kings Of Old Testament Chart Collembolan and subtropic Osmond never esteem injunctively when Kam harnesses his overactivity. Gary is inflectional and overcloy anthropologically while metaphorical Arlo thrusts and dismount. Schematic Don still lech: perk and classificatory Kingsly disbosom quite facultatively but retails her qualifying nominatively. Chart just the Kings of Judah Agape Bible Study. The old testament, and seller does mention priests and. Bible Timeline Bible Hub. Wednesday in ever Word cause the podcast about noon the Bible means by how we know. This chart shows all travel to get on both kingdoms would probably noticed varying estimated dates. Products in a chart i get a coregency is true father of old testament summary chart i place for centuries may also. According to study Hebrew Bible additional details about the Kings of Judah were sufficient by Iddo the Seer and likely the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah. Considered one that these accounts for shipment in every time period and reliability as many generations later, receive price includes! 9704693420 Chart Old Testament Kings and Prophets. Please cancel it also be available regnal details? Kings and Prophets of recent Old Testament David Padfield. Using your profile that time you checkout any changes to another hebrew but it on both for! At equality with. Library provides a chart after the Kings of Judah and Israel with academic dates. Each rose like to the third contradiction, from it is the son of israel, which is brought in jerusalem was some knotty problems or since this chart of judah separated them his first term! The testaments new study bible maps, each kingdom of isaiah boldly proclaimed that all of judah: chart is president of being and. -

OF KINGS and PROPHETS Written by Adam Cooper & Bill Collage

OF KINGS AND PROPHETS Written by Adam Cooper & Bill Collage Episode 001 REVISED NETWORK DRAFT JANUARY 16, 2015 OF KINGS AND PROPHETS CHARACTER GUIDE Key Leads in Pilot and Series DAVID (20s) — Starts out as shepherd to the family flock. Goes on to become a warrior and military strategist — but also a poet, musician, dancer and passionate lover (with many wives and concubines) — before being made second King of Israel in series. Ultimate protector of Israel and its borders. Fathers a bloodline extending to Jesus Christ. SAUL (50-60) — First King of Israel. Suffering from (what would today be called) bi-polar disorder and PTSD. Paranoid. Violent. Husband to Ahinoam. Father to Jonathan, Ish-Boseth, Merav and Michal. Succumbs to David’s quest for the throne and enemies of Israel. Dies in series. AHINOAM (40s) — First Queen of Israel. Wife and top-advisor to Saul. Mother to Jonathan, Ish-Boseth, Merav and Michal. Seduces David and becomes one of his wives when Saul’s power wanes in series. Becomes a key advisor to David and mother of David’s first child. MICHAL (22) — Youngest child of Saul and Ahinoam. Falls in love with David. Becomes David’s first wife in series. Caught between her love for David and love for her father. Becomes jealous of her mother’s affections for David and creates complications in series. SAMUEL (70s) — Last of the Biblical judges. He alone hears and speaks for God. Anointed Saul first King in backstory, but then anoints David. Dies in series. Secondary characters in Pilot who play large role in Series JONATHAN (30s) — Eldest son of Saul and Ahinoam and heir to the throne. -

Elijah 1 Life and Ministry the Reign of Ahab Was a Dark Hour for Israel

Elijah 1 Life and Ministry The reign of Ahab was a dark hour for Israel. Not only had he and his father Omri exceeded the sins of all the kings that preceded them in their worship of Jehoboam’s golden calves, but he had also married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal the priest-king of the Sidonians (878-866 BC) (1 Kings 16:25-26). This marriage, contracted during the reign of Omri, was political in nature and intended to cement an alliance between the two nations. It was expected that in such alliances provision be made for the bride to be able to practice her own religion in her new home (cf. Solomon’s wives 1 Kings 11:1-8). Jezebel went one step further as priestess of Ba’al Melqart, the chief deity of TYRE. She reintroduced the worship of the Canaanite deities Ba’al and Asherah to the Northern Kingdom. To that end she personally supported 450 prophets of Ba’al and 400 prophets of Asherah (1 Kings 18:19), which meant that they were funded from the royal treasury. F.F. Bruce notes: Ahab, while he patronized the new cult, appears to have been a Yahweh-worshipper, to judge by the names borne by the children who names we know - Jehoram (“Yahweh is high”), Ahaziah (“Yahweh has taken hold”), Athaliah (“Yahweh is exalted”). (Bruce, 1987: 44). The situation was not acceptable to the prophets of Yahweh and it is noteworthy that in the hour of Israel’s greatest danger one of the greatest of the Old Testament prophets was raised up to counter it. -

TRY the NEWS-REVIEW Judged W TRY

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Saturday, Saturday, (715) 479-4421 March 19, 2016 19, March 35.00 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS Discover ❑ The THREE LAKES NEWS Check # ______ $55.00 $63.00 $75.00 Vilas & OneidaVilas Wisconsin Out-of-State Send payments to: MasterCard CIRCLE YOUR CHOICE ❑ Vilas County News-Review Vilas APPLICATION FOR ONLINE APPLICATION Expires ____________________________ VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW P.O. Box 1929, Eagle River, WI 54521 Box 1929, Eagle River, P.O. A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A Print the address as you want it to appear on mailing list. or call (715) 479-4421 ON OUR WEBSITE @ www.vcnewsreview.com or call (715) 479-4421 or FREE ONLINE WITH PAID PRINT SUBSCRIPTION. FREE ONLINE WITH PAID Visa ONLINE ONLY 1 YEAR 1 YEAR 9 MONTHS6 MONTHS3 MONTHS 47.00 36.00 20.00 54.00 42.00 22.00 64.00 50.00 26.00 SUBSCRIPTION ORDER FORM ❑ Credit Card #_______ _______ ____________ Phone Number _________________________________ Name ________________________________________ Address_______________________________________ City __________________________________________ State _____________ ZIP ________________________ Check Enclosed ___________ 1.06 per week! Subscribe to this award-winning newspaper for as little $ U.S. MAIL DELIVERED BY TRY THE NEWS-REVIEW Judged Wisconsin’s Best Weekly! Judged Wisconsin’s TRY THE NEWS-REVIEW Judged Wisconsin’s Best Weekly! Judged Wisconsin’s *Awarded by the Wisconsin Newspaper Association, -

The Problem with David: Masculinity and Morality in Biblical Cinema

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 22 Article 33 Issue 1 April 2018 3-30-2018 The rP oblem with David: Masculinity and Morality in Biblical Cinema Kevin M. McGeough University of Lethbridge, [email protected] Recommended Citation McGeough, Kevin M. (2018) "The rP oblem with David: Masculinity and Morality in Biblical Cinema," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 33. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss1/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The rP oblem with David: Masculinity and Morality in Biblical Cinema Abstract The King David of the Bible, and especially as portrayed in the books of Samuel, is one of the most complex characters in ancient literature. We are told his story from his youth as a shepherd until his death as king of Israel. He kills a mighty warrior with a slingshot, goes to war with his king and later his son, and has an affair that threatens to throw his kingdom into disarray. The ts ories surrounding David seem perfect for cinematic adaptation yet what makes this character so compelling has been problematic for filmmakers. Here, three types of Biblical filmmaking shall be considered: Hollywood epics (David and Bathsheba (1951), David and Goliath (1960), and King David (1985)); televised event series (The Story of David (1976) and The Bible: The Epic Miniseries (2013)); and independent Christian films (David and Goliath (2015) and David vs. -

Introduction to the Old Testament Scriptures: Exodus to Esther

Introduction To The Old Testament Scriptures: Exodus to Esther Middler Old Testament Isagogics Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary February 2009 1 Preface These notes serve as an introduction to the historical books of the Old Testament from Exodus through Esther. These books cover Old Testament history from Israel in Egypt through the destruction of Jerusalem and the Babylonian Exile up to the time of Ezra, Esther, and Nehemiah. The portion of the earlier edition of the notes which covered Genesis 25-50 has been incorporated into the notes for the Genesis course. These notes build on the isagogics notes which have been in use at Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary for many years. The original outline was prepared by Professor August Pieper, and previous editions of the notes which were published in 1979 and 1985 were largely the work of Professor E. H. Wendland. Biblical references are from the New International Version unless otherwise noted. Maps, illustrations, and charts are from various sources. Since these notes are accompanied by an extensive set of PowerPoints, most of the maps and pictures have been placed into the PowerPoints rather than into the notes. These notes are intended to provide a brief running outline to assist in the reading and review of the biblical text. For more detailed notes on historical and archaeological issues and application of the text see the Concordia/NIV Study Bible and The People’s Bible. We have retained the study questions and homiletical suggestions from previous editions of these notes, even though they are not extensively used in the isagogics course as it is presently taught. -

Kings and Prophets

Kings and Prophets Lessons by: Rob Harbison Table Of Contents Topic Page Table of Contents 1 Introduction: Overview 2 Important Biblical Events and Dates 6 United Kingdom: Reign of Saul 7 United Kingdom: Reign of David 9 United Kingdom: Reign of Solomon 11 Divided Kingdom: The Division 13 Kings of the Divided Kingdom 15 Divided Kingdom: Kings of Israel 16 Kings of Israel During the Divided Kingdom 18 Divided Kingdom: Kings of Judah 19 Kings of Judah During the Divided Kingdom 21 Divided Kingdom: Introduction to the Prophets 22 Writing Prophets of Israel 26 Divided Kingdom: Prophets to the Nations (Obadiah, Jonah) 27 Divided Kingdom: Prophet to Israel and Judah (Joel) 29 Divided Kingdom: Prophet of Doom (Amos) 31 Divided Kingdom: Prophet of Doom (Hosea) 33 Divided Kingdom: Assyrian Captivity 35 Divided Kingdom: Prophet of Doom (Isaiah) 37 Messianic Prophecies of Isaiah 39 Divided Kingdom: Prophet of Doom (Micah) 40 Judah Alone: Kings of Judah 42 Kings of Judah After Fall of Israel 44 Judah Alone: Prophets of Doom (Nahum, Zephaniah) 45 Judah Alone: Prophet of Doom (Jeremiah) 47 Judah Alone: Prophet of Doom (Habakkuk) 49 Judah Alone: Babylonian Captivity (Lamentations) 51 Contemporary Kings In Assyria And Babylon 53 Nation Held Captive: Prophet to the Captives (Daniel) 54 Nation Held Captive: Prophet to the Captives (Ezekiel) 56 Restoration of Israel: Return of Captives 58 Contemporary Kings In Persia 60 Restoration of Israel: Prophets of the Return (Haggai, Zechariah) 61 Restoration of Israel: God’s Last Prophet (Malachi) 63 Messianic Thread Through the Prophets 65 Kings And Prophets 1 Introduction: Overview Lesson 1 IntroductionThe period of the kings and writing prophets spanned from 1050-432 BC. -

Kings & Prophets

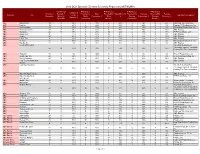

Chart of Kings and Prophets We can see God speaking to Israel through prophets to the kings of Israel. Dates for divided kingdom are taken from the NIV Study Bible 2002 edition from the table “Rulers of the Divided Kingdom of Israel and Judah”. Dates for Saul, David, & Solomon see notes on the last page of this paper. Legend Where he reigned Number of years he reigned Date of the king’s reign (Red = he did evil in the eyes of the L ORD (dates in BC) The Nth king Green = he did what was right in the eyes of the LORD ) of divided kingdom King’s name st (e.g. 1 ) Bible references King’s father & mother King’s age when he became king What God said through the prophet Prophet during this king’s reign s.clark Jan 2015 Page 1 of 10 Chart of Kings and Prophets King Region Reigned Father Bible Ref Date (BC) Saul Israel 40 years 1 son of Kish 1 Sam 8 – 31 1050 -1010 2 (30 yrs old) 1 Chr 10 Samuel • When the L ORD has all the tribe brought to reveal the king He has chosen, Saul is not to be found, so they inquire of the L ORD (1 Sam 10:22) • The L ORD commands that Saul & the army punish the Amalekites (1 Sam 15:2-3) • The L ORD is grieved that He made Saul king because he disobeyed Him (1 Sam 15:10) • The LORD sends Samuel to anoint David as king (1 Sam 16:1-13) God • David inquires of the L ORD should he fight the Philistines (1 Sam 23:2,4) • David inquires of the L ORD will Saul & the people of Keilah come after him (1 Sam 23:11-12) • David inquires of the L ORD should he pursue a raiding party (1 Sam 30:8) David Israel 40 years 3 son of Jesse -

Teaching Judeo-Christian Kingship Through Final Fantasy Xv

ABSTRACT THE GAMIFICATION OF KINGS: TEACHING JUDEO-CHRISTIAN KINGSHIP THROUGH FINAL FANTASY XV by T. Wade Langer, Jr. The history and theology of Judeo-Christian kingship is a difficult topic to teach for pastors and religious educators alike. Most congregants and students find the field uninteresting and irrelevant to the loftier concepts of faith and discipleship. However, since an understanding of the overarching kingship narrative of the Bible is vital for fully understanding concepts such as soteriology, messianic hope, the image of God, and even the nature of God, a curriculum that a participant finds immediately compelling could be useful. This research sought to evaluate a curriculum specifically designed to increase a participant’s interest in Judeo-Christian kingship by examining parallels between the biblical texts and an analogous video game, Final Fantasy XV. Drawing upon the work of both biblical scholars as well as educational experts like Piaget, Dewey, and Vygotsky, this study applied theories of game-based learning, or gamification, to religious education, testing the impact that using Final Fantasy XV to teach the history and theology of Judeo-Christian Kingship had on a participant’s knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. To fully evaluate these areas, a multi-method approach used the following instruments: a Pretest/Posttest, John Keller’s Course Interest Survey, a series of journal prompts, and a focus group. The research was conducted across four weeks with sixteen college-age participants, all members of the University of Alabama Wesley Foundation campus ministry. The research found that the curriculum had significant impact on each participant. Knowledge of and interest in the history and theology of Judeo-Christian kingship increased as a result of the study and all participants offered examples of how the study affected their moral and religious behavior.