New Testament Textual Criticism in America: Requiem for a Discipline*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl Lachmann Und Die Schriften Der Römischen Landvermesser

Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig Karl Lachmann und die Schriften der römischen Landvermesser Schindel, Ulrich Veröffentlicht in: Abhandlungen der Braunschweigischen Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft Band 57, 2006, S.35-53 J. Cramer Verlag, Braunschweig http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00048799 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig AbhandlungenKarl der Lachmann BWG und · die Schriften 57 : 35–53 der römischen · Landvermesser Braunschweig, Mai 2007 35 Karl Lachmann und die Schriften der römischen Landvermesser* ULRICH SCHINDEL Albert-Schweitzer-Straße 3 D-37075 Göttingen Wer das Braunschweigische Landesmuseum besucht, erblickt in dessen Foyer eine Reihe von Porträtphotographien der großen Söhne Braunschweigs. Darun- ter sind zwei berühmte Professoren, Karl Friedrich Gauss, Mathematiker, Physi- ker, Astronom in Göttingen, und Karl Lachmann, Klassischer Philologe, Germa- nist, Theologe in Berlin. Der Erstgenannte ist im Jahr 2005 vielfach gefeiert worden, von dem Zweiten und einem seiner ungewöhnlichsten Werke soll jetzt die Rede sein: nicht nur Braunschweig als seine Heimatstadt sondern auch der technisch-mathematische Inhalt dieses Werks laden dazu ein. In einem Drei- schritt will ich das Thema Ihnen nahe bringen: am Anfang soll eine Skizze von Leben und Wesen Lachmanns stehen; dann will ich mich dem wichtigsten Hilfs- mittel zuwenden, welches der Edition Lachmanns zugrunde liegt, der berühm- ten spätantiken Agrimensoren-Handschrift, die seit alters ein Glanzstück der nahen Herzog-August-Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel darstellt, und schließlich will ich der Frage nachgehen, wieso sich Lachmann diesem für ihn so untypischen Thema zugewandt hat. I. Karl Konrad Friedrich Wilhelm Lachmann wurde am 4. März 1793 geboren als Sohn des Pfarrers an der Braunschweiger St. Andreas-Kirche1 . Der Vater war vorher Feldprediger in Preußen gewesen; die Mutter, Tochter eines preußischen Majors, starb schon, als Karl Lachmann erst zwei Jahre alt war. -

The Textual Reliability of the New Testament: a Dialogue

1 x The Textual Reliability of the New Testament: A Dialogue Bart D. Ehrman and Daniel B. Wallace OPENING REMARKS Bart D. Ehrman Thank you very much; it’s a privilege to be with you. I teach at the University of North Carolina. I’m teaching a large undergraduate class this semester on the New Testament, and of course, most of my students are from the South; most of them have been raised in good Christian families. I’ve found over the years that they have a far greater commitment to the Bible than knowledge about it. So this last semester, I did something I don’t normally do. I started off my class of 300 students by saying the first day, “How many of you in here would agree with the proposition that the Bible is the inspired word of God?” Voom! The entire room raises its hand. “Okay, that’s great. Now how many of you have read The Da Vinci Code?” Voom! The entire room raises its hand. “How many of you have read the entire Bible?” Scattered hands. “Now, I’m not telling you that I think God wrote the Bible. You’re telling me that you think God wrote the Bible. I can see 13 14 THE RELIABILITY OF THE NEW TESTAMENT why you’d want to read a book by Dan Brown. But if God wrote a book, wouldn’t you want to see what he had to say?” So this is one of the mysteries of the universe. The Bible is the most widely purchased, most thoroughly read, most broadly misunderstood book in the history of human civilization. -

Chapter One Inventing the Linguistic Monuments of Europe1

Chapter One Inventing the Linguistic Monuments of Europe1 No one, professional historian or member of the interested public, comes to the Middle Ages without preconceptions, assumptions, and expectations about this long period of European history. These preconceptions derive not only from popular media including film, fiction, and the internet, but also from centuries of debate and fashioning and refashioning of this long period by scholars who sought not only to understand the past but to mobilize it for debates about their own presents. The Middle Ages have never been merely academic—the continuing fascination with the medieval world has always had implications for the understanding of the present, a search for those models, paradigms, and structures, both social and mental, that define the present. Essential to this process has always been the search for those objects and especially those texts generated during this period, and concomitantly the search for how to understand these documents. The two are intimately interconnected: the selection and privileging of specific documents has always been in relationship to the questions historians have asked, and documents, as they are discovered or rediscovered are made to fit into patterns of meaning by the scholars who have discovered them. While the search for medieval texts has been carried on since the sixteenth century for a spectrum of religious, political, and ideological reasons, the Middle Ages that we study is for better or worse largely a construct of the nineteenth century. Our corpus of sources owe their preservation and publication to the passion of long-forgotten scholars who sought them out because they hoped that they would answer specific questions about the past and the present, questions and interpretations that subsequent generations of scholars and the general public have largely accepted without question. -

The Spirit of Lachmann, the Spirit of Bédier: Old Norse Textual Editing in the Electronic Age by Odd Einar Haugen

The spirit of Lachmann, the spirit of Bédier: Old Norse textual editing in the electronic age by Odd Einar Haugen Paper read at the annual meeting of The Viking Society, University College London, 8 November 2002 Electronic version, 20 January 2003 Introduction In this paper I would like to discuss some central aspects of textual editing, as it has been practised in Old Norse studies for the past century, and since we now are at the beginning of a new century, I shall venture some opinions on the direction of textual editing in the digital age. I shall do so by beginning with two key figures of modern textual history, the German scholar Karl Lachmann (1793–1851) and the French scholar and author Joseph Bédier (1864–1938). Their approaches to the art and science of editing are still highly relevant. Lachmann The scientific foundation of textual editing has been credited to Karl Lachmann and other classical scholars such as Karl Gottlob Zumpt (1792–1849), Johan Nicolai Madvig (1804–1886) and Friedrich Ritschel (1806–1876). Lachmann himself was active in the fields of Medieval editing, with Nibelungen lied (1826), in Biblical studies, with his new edition of the Greek New testament (1831), and in Classical scholarship, with his edition of Lucrets’ De rerum natura (1850). This made Lachmann’s name known throughout all fields of textual editing, and with some reservations it is probably fair to attach his name to the great changes of editorial techniques made in the begin- ning of the 19th century. However, as Sebastiano Timpanaro (1923–2000) points out in his important study of Lachmann’s contribution, Die Entstehung der Lachmannschen Methode (1971), the method was basically a method of genealogical analysis. -

The Rule of Christian Faith, Practice, and Hope: John

Meth od ist Re view, Vol. 3 (2011): 1–35 The Rule of Chris tian Faith, Prac tice, and Hope: John Wesley on the Bi ble Randy L. Mad dox Ab stract JOHN WESLEY in sisted that a good theo lo gian must be a good textuary (student of bibli cal texts). This es say sur veys his model as a textuary, highlight - ing in sights from re cent sec ond ary stud ies and pro vid ing some new ev i dence from just-re leased sources. The first sec tion fo cuses on what Bi ble Wes ley read, probing his assump tions about canon and his empha sis on study ing Scrip ture in the orig i nal lan guages. The sec ond sec tion de tails sev eral di men sions of how Wes ley read the Bi ble, with par tic u lar at ten tion to his “theo log i cal” read ing of Scrip ture and the iden ti fi ca tion of his dis tinc tive “work ing canon.” The fi nal sec tion turns to why Wes ley read the Bi ble, stress ing that he val ued Scrip ture for more than just a guide to Chris tian faith. His stron gest em pha sis was on Scrip ture as a “means of grace” for nur tur ing Chris tian life, and his life-long prac tice of im mer sion in Scrip ture served to sus tain and broaden his sense of the Christian hope. A IT HAS BECOME TRADI TIONAL —in deed, al most oblig a tory—to be gin presentations on John Wes ley’s ap pre ci a tion for and ap proach to in ter pret ing the Bi ble with the fol low ing ex cerpt from his pref ace to the first vol ume of his Ser mons on Sev eral Oc ca sions: Published in Methodist Review: A Journal of Wesleyan and Methodist Studies ISSN: 1946-5254 (online) s URL: www.methodistreview.org 2 Methodist Review, Vol. -

Future Philology! by Ulrich Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff - Rt Anslated by G

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections 2000 Future Philology! by Ulrich von Wilamowitz- Moellendorff - rT anslated by G. Postl, B. Babich, and H. Schmid Babette babich Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Continental Philosophy Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation babich, Babette, "Future Philology! by Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff - rT anslated by G. Postl, B. Babich, and H. Schmid" (2000). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 3. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE PHILOLOGY!i a reply to FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE’S Ordinarius Professor of Classical Philology at Basel „birth of tragedy“ by Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Möllendorff Dr. Phil. zÏîùô óéëöéùô âáë&Òò ôåýôëéïí ßðüôñéììá hñÃïí ¦ãêÝöáëïí Ïñßãáíïí êáôáðõãïóýíç ôáØôz ¦óô ðñÎò êñåáò ìÝãá. — Aristophanes, Age 17ii i Zukunftsphilologie is a play upon the 1861 German publication of Wagner’s ironically titled “Zukunftsmusik” [“Music of the Future” — the quotation marks are Wagner’s own], an open letter to Frederic Villot, Conservator of the Picture Museums at the Louvre, first translated into and published in French in 1860. See L. J. Rather, Reading Wagner: A Study in the History of Ideas (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998), p. -

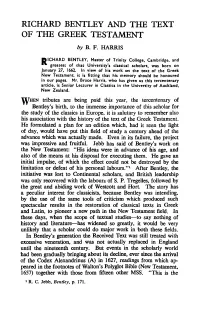

Richard Bentley and the Text of the Greek Testament

RICHARD BENTLEY AND THE TEXT OF THE GREEK TESTAMENT by B. F. HARRIS RICHARD BENTLEY, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and greatest of that University's classical scholars, was born on January 27, 1662. In view of his work on the text of the Greek New Testament, it is fitting that his memory should be honoured in our pages. Mr. Bruce Harris, who has given us this tercentenary article, 'is Senior Lecturer in Classics in the University of Auckland, New Zealand. WHEN tributes are being paid this year, the tercentenary of Bentley's birth, to the immense importance of this scholar for the study of the classics in Europe, it is salutary to remember also his association with the history of the text of the Greek Testament. He formulated a plan for an edition which, had it seen the light of day, would have put this field of study a century ahead of the advance which was actually made. Even in its failure, the project was impressive and fruitful. Jebb has said of Bentley's work on the New Testament: "His ideas were in advance of his age, and also of the means at his disposal for executing them. He gave an initial impulse, of which the effect could not be destroyed by the limitation or defeat of his personal labours."l After Bentley, the initiative was lost to Continental scholars, and British leadership was only recovered with the labours of S. P. Tregelles, followed by the great and abiding work of Westcott and Hort. The story has a peculiar interest for classicists, because Bentley was intending, by the use of the same tools of criticism which produced such spectacular results in the restoration of classical texts in Greek and Latin, to pioneer a new path in the New Testament field. -

The Freedom to Change the Text of the New Testament? Wettstein’S Treatment of Mark

Chapter 7 The Freedom to Change the Text of the New Testament? Wettstein’s Treatment of Mark Jan Krans and Silvia Castelli * 1 Introduction In order to understand the nature of Wettstein’s edition,1 it is important to locate it within the larger history of New Testament Textual Criticism.2 Periods for the history of the printed text of the Greek New Testament can roughly be discerned as follows. (1) The beginnings, with Erasmus’s 1516 edition and the 1520 Complutensian Polyglot, up to the firm establishment of the Textus Receptus (TR), including its name, with the Elzevier editions of 1624 and 1633. (2) The collection of variant readings, and various efforts of revision of the TR, up to Lachmann. (3) The overthrow of the TR and the establishment of a mod- ern critical text, from Lachmann’s 1830 edition to Nestle’s first edition in 1898. (4) The confirmation, extension and refinement of the modern critical text, and the historical turn in Textual Criticism. Perhaps we are now on the brink of a completely new era, marked by the digital revolution. These periods also correspond to development of text-critical rules and theory. In the first period text-critical reasoning was there, sometimes even in sophisticated ways, but not systematically and without a good grasp of the relative value of manuscripts. In the second period canons of text-critical rules * A first draft of this article was first presented at the SBL international meeting in Amsterdam, July 2012, and in a modified form at the Wettstein conference organised by NOSTER in Amsterdam, November 2012. -

J. A. Bengel," Lives of the Leaders of Our Church Universal, Ed

J. ¡. BENGEL — "Full of Light" ANDREW HELMBOLD, Ph.D. Among the luminaries of the Lutheran Church, none should shine brighter than Johann Albrecht Bengel, who has met the underserved fate of being known only in academic circles. Yet he certainly was the greatest Biblical scholar of his century, and made more lasting contributions to Biblical studies than many more famous men. The purpose of this article is to point out those contributions. To do so one must look at Bengel's life and character, for his studies were the direct re- sult of his own spiritual experience. Bengel as a Christian Bengel was born to a Lutheran parsonage family at Winnenden, Germany, on June 24, 1678. He lost his father at the age of six. As a child he read Arndt's True Christianity and Francke's Introduction to the Reading of the Scriptures.1 Thus early was he influenced by the pietistic movement, although the never became a pietist. In later life he used Arndt's work and Francke's Sermons and Muller's Hours of Refreshing in family devotions. He completed his theological education at Tubingen in 1706. Then followed a curacy at City Church, Tubingen, a period as theological répètent at his alma mater, another curacy at Stuttgart, and a pro- fessorship at Denkendorf (1713-1741) which he left only to serve as prelate of the church. His home was blessed with twelve children, but six died in infancy. His comfort in his hours of sorrow was that "if a vacancy has been made in his family circle, another vacancy had been filled up in heaven."2 At his death, on Nov. -

The Textual History of the Greek New Testament Society of Biblical Literature

The Textual History of the Greek New Testament Society of Biblical Literature Text-Critical Studies Editor Sidnie White Crawford Number 8 The Textual History of the Greek New Testament The Textual History of the Greek New Testament Changing Views in Contemporary Research Edited by Klaus Wachtel and Michael W. Holmes Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta The Textual History of the Greek New Testament Copyright © 2011 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The textual history of the Greek New Testament / edited by Klaus Wachtel and Michael W. Holmes. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature text-critical studies ; no. 8) Proceedings of a colloquium held in 2008 in M?nster, Germany. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-58983-624-2 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-625-9 (electronic format) 1. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, Textual—Congresses. I. Wachtel, Klaus. II. Holmes, Michael W. (Michael William), 1950- BS2325.T49 2011 225.4'86—dc23 2011042791 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI /NISO Z39.48–1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

A New Descriptive Inventory of Bentley's Unfinished New Testament Project

TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 25 (2020): 111–128 A New Descriptive Inventory of Bentley’s Unfinished New Testament Project* An-Ting Yi, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Jan Krans, Protestantse Theologische Universiteit, Amsterdam Bert Jan Lietaert Peerbolte, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam One of Eldon J. Epp’s areas of expertise is the scholarly history of New Testament textual criticism. He offers an excellent overview of its different stages, including Bentley’s un- finished New Testament project. Yet, many aspects can be refined by studying the -ma terials left by Bentley, preserved at Wren Library of Trinity College (TCL), Cambridge. This contribution offers an up-to-date descriptive inventory of all the remaining archive entries, containing bibliographical information, precise descriptions, relevant second- ary literature, and parts of the reception history. 1. Introduction1 One of Eldon J. Epp’s lifelong interests is the history of New Testament textual scholarship. No- tably his two articles in The New Cambridge History of the Bible not only distinguish periods for the history of the printed Greek New Testament text, but they also become a standard reference for those who want to delve into this issue.2 In these contributions he draws an encompassing picture of the historical developments of text-critical methods of the New Testament, begin- ning from Erasmus until the present day. A key figure contributing to these developments is the renowned eighteenth-century Cambridge classical scholar Richard Bentley (1662–1742). In fact, Epp already mentioned Bentley’s name and his famous Proposals for Printing of 1720 in a 1976 article when tracing the history of the “critical canons” of the New Testament text.3 Since * Our thanks first go to the staff of Wren Library of Trinity College, who generously helped us during our stay in Cambridge, November 2018. -

Und Seminararbeiten in Der Germanistischen Mediävistik

Ergänzende Hinweise zu Proseminar- und Seminararbeiten in der Germanistischen Mediävistik Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. PROSEMINARARBEITEN UND SEMINARARBEITEN (BACHELOR-ARBEITEN) ................................. 2 1.1 GRUNDSÄTZLICHES ................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 FORMALES, HANDWERKSZEUG .............................................................................................. 3 1.3 BESONDERHEITEN BEIM ARBEITEN MIT UND ZITIEREN VON MITTELALTERLICHEN TEXTEN 3 1.4 LITERATURANGABEN ............................................................................................................. 4 1.5 ZITATE ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1. PROSEMINARARBEITEN UND SEMINARARBEITEN (BACHELOR-ARBEITEN) 1.1 GRUNDSÄTZLICHES (1) Ausgangspunkt für die Erarbeitung der Fragestellung der Arbeit ist das Proseminar bzw. das Seminar. Von der Arbeit im Proseminar/Seminar ausgehend sollte man zu einer spezifischen, enger gefassten Fragestellung kommen. (2) Proseminararbeiten und Seminararbeiten müssen eine solche – in der Einleitung knapp und präzise formulierte – Fragestellung (ein zu lösendes Problem) aufweisen. (3) Wenn Sie über eine mögliche Fragestellung nachgedacht haben und diese formuliert haben, Forschungsliteratur recherchiert und begonnen haben, diese zu lesen und zu exzerpieren, dann nehmen Sie bitte Kontakt mit dem_der Dozierenden auf. (4) Proseminararbeiten