Me, the Jokerman: Enthusiasms, Rants \& Obsessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ssc Special Daily Quiz -740 Total Questions-40, Time - 40 Minutes, Marks - 40 Arena of General Knowledge 1

DAILY QUIZ-740 (11.09.2019) TEST YOURSELF SSC SPECIAL DAILY QUIZ -740 TOTAL QUESTIONS-40, TIME - 40 MINUTES, MARKS - 40 ARENA OF GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. Which of the following is in liquid form at room temperature? (a) Cerium (b) Sodium (c) Francium (d) Lithium 2. Soda water contains (a) Nitrous Acid (b) Carbonic Acid (c) Carbon Dioxide (d) Sulphur Acid 3. Which of the following is not an isotope of hydrogen? (a) Protium (b) Yttrium (c) Deuterium (d) Trituim 4. Polythene is industrially prepared by the polymerization of (a) Methane (b) Styrene (c) Acetylene (d) Ethylene 5. Which of the following is not a chemical reaction? (a) Burning of Paper (b) Digestion of Food (c) Conversion of Water into Steam (d) Burning of Coal 6. What is condensation? (a) Change of Gas into Solid (b) Change of Solid into Liquid (c) Change of Vapour into Liquid (d) Change of Heat Energy into Cooling Energy 7. During the development of an embryo the formation of brain marks the beginning of organ formation. Eye in a vertebrate develops from midbrain. If after the formation of brain the mid brain is destroyed then what will be the resultant effect? (a) Total Failure of Eye Formation (b) Development of a Single Eye (c) Defective Development of Eyes (d) Absence of Vision in the Eyes 8. The artificial rearing of honey bees is called (a) Sylviculture (b) Sericulture (c) Apiculture (d) Lociculture 9. Pineapple is a (a) Single Fruit (b) Collection of Fruit (c) Stem of the Plant (d) Collection of Leaves 10. The disease trachoma is related to the (a) Eye (b) Ear (c) Mouth (d) Throat 11. -

The Mahatma As Proof: the Nationalist Origins of The

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77d6z8xw Author Shingavi, Snehal Ashok Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism by Snehal Ashok Shingavi B.A. (Trinity University) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Prof. Abdul JanMohamed, chair Prof. Gautam Premnath Prof. Vasudha Dalmia Fall 2009 For my parents and my brother i Table of contents Chapter Page Acknowledgments iii Introduction: Misunderstanding the Mahatma: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism 1 Chapter 1: The Mahatma as Proof: the nationalist origins of the historiography of Indian writing in English 22 Chapter 2: “The Mahatma didn’t say so, but …”: Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable and the sympathies of middle-class 53 nationalists Chapter 3: “The Mahatma may be all wrong about politics, but …”: Raja Rao’s Kanthapura and the religious imagination of the Indian, secular, nationalist middle class 106 Chapter 4: The Missing Mahatma: Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi and the genres and politics of Muslim anticolonialism 210 Conclusion: Nationalism and Internationalism 306 Bibliography 313 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, this dissertation would have been impossible without the support of my parents, Ashok and Ujwal, and my brother, Preetam, who had the patience to suffer through an unnecessarily long detour in my life. -

Sadir, Bharatanatyam, Feminist Theory Sriv1dya

ANOTHER STAGE IN THE LIFE OP THE NATION: SADIR, BHARATANATYAM, FEMINIST THEORY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES SRIV1DYA NATARAJAN FEBRUARY, 1997 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Ms. Srividya Natarajan worked under my supervision for the Ph.D. Degree in English. Her thesis entitled "Another Stage in the Life of the Nation: Sadir. Bharatanatyam. Feminist Theory" represents her own independent work at the University of Hyderabad. This work has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of any degree. Hyderabad Tejaswini Niranjana Date: 14-02-1997 Department of English School of Humanities University of Hyderabad Hyderabad February 12, 1997 This is to certify that I, Srividya Natarajan, have carried out the research embodied in the present thesis for the full period prescribed under Ph.D. ordinances of the University. I declare to the best of my knowledge that no part of this thesis was earlier submitted for the award of research degree of any University. To those special teachers from whose lives I have learnt more than from all my other education put together: Kittappa Vadhyar, Paati, Thatha, Paddu, Mythili, Nigel. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the course of five years of work on this thesis, I have piled up more debts than I can acknowledge in due measure. A fellowship from the University Grants Commission gave me leisure for full-time research; some of this time was spent among the stacks of the Tamil Nadu Archives, the Madras University Library, the Music Academy Library, the Adyar Library, the T.T. -

Nargas-Bhai Vir Singh English.Pdf

Page 1 www.sikhbookclub.com Nargas Bhai Vir Singh Translated by Prof. Puran Singh 1924 ]. M. Dent) London 1961 veekay *ekly, Bombay 1972 Punjabi University) Patiala 2001 Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan) New Delhi © BhaiVirSingh SahityaSadan,NewDelhi Publisher : BhaiVirSinghSahityaSadan, BhaiVirSinghMarg, NewDelhi Printer: Bhai Vir SinghPress, Bhai Vir SinghMarg, NewDelhi Rs.40/- Page 2 www.sikhbookclub.com INTRODUCTION Nargas : Songs of a Sikh presents an I~nglish version of selected poems of Bhai Vir Singh who is remembered as the father of modern Punjabi literature. At once a poet, a novelist, a playwright, a historian, a theologian, and a lexicographer, he has been, perhaps the most versatile man of letters of modern Punjab. His verse portrays rare mystic insights especially as revealed through nature. First published in 1924 by J. M. Dent in London, this book Nargas, carried a foreword by Ernest Rhys. In 1961 Veekay Weekly, Bombay, brought out its first Indian edition to commemorate the 4th death anniversary of the poet. Punjabi University, Patiala, published a reprint of it in 1972, on the occasion of the first birth centenary of Bhai Vir Singh. Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan has chosen to bring out the present edition auguring the proposed programme of translation of the poet's entire works. In this edition., for the convenience of those readers who may like also to gain access to the original the Punjabi title of each original poem has been provided underneath each respective translation. The selection as well as translation of the poems in this book was made by none other than Professor Puran Singh, an ardent admirer of Bhai Vir Singh. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

Volume Ninety-Four : (Feb 17, 1947

1. A LETTER DEVIPUR , February 17, 1947 My reply to your previous letter was still pending when I got this second one from you. But there was nothing in your first letter that needed immediate reply. At present there is great strain on me, both physical and mental. My work here instead of getting easier is becoming more difficult each day, as oppsition is increasing. All the same, my faith and courage are steadily growing. After all, I am here to do or die, am I not? There is no middle course here. .1 It is not certain when the third stage of my tour will begin. I have to reach Haimchar on the 24th. .2 The further programme will depend on how exhausted I feel. I shall be satisfied if God sustains me through the programme even up to the 24th. [From Gujarati] Eklo Jane Re, p. 144 2. ADVICE TO A CONGRESS WORKER3 DEVIPUR , February 17, 1947 Did you realize that by indulging in this vain display you would acerbate communal passions? This display means nothing to me. .4 but it will leave a legacy of ill-will behind which will continue to poison the communal relations in this village for a long time to come. You are a Congressman. Did not it occur to you, knowing my strong views on khadi, that ribbons and buntings made of mill cloth would only hurt me? I wouldn’t have felt so hurt if, instead of floral decorations, you had presented me with garlands of yarn. They are decorative, and 1 Omissions as in the source 2 Ibid 3 A grand reception had been arranged for Gandhiji at Devipur. -

Afrindian Fictions

Afrindian Fictions Diaspora, Race, and National Desire in South Africa Pallavi Rastogi T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss C O L U MB us Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rastogi, Pallavi. Afrindian fictions : diaspora, race, and national desire in South Africa / Pallavi Rastogi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0319-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0319-1 (alk. paper) 1. South African fiction (English)—21st century—History and criticism. 2. South African fiction (English)—20th century—History and criticism. 3. South African fic- tion (English)—East Indian authors—History and criticism. 4. East Indians—Foreign countries—Intellectual life. 5. East Indian diaspora in literature. 6. Identity (Psychol- ogy) in literature. 7. Group identity in literature. I. Title. PR9358.2.I54R37 2008 823'.91409352991411—dc22 2008006183 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–08142–0319–4) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–08142–9099–6) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Typeset in Adobe Fairfield by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction Are Indians Africans Too, or: When Does a Subcontinental Become a Citizen? 1 Chapter 1 Indians in Short: Collectivity -

Tne Qjlassical Uoicinq Ine Miooern

tne Qjlassical J J Uoicinq ine Miooern THE POSTCOLONIAL POLITICS OF MUSIC IN SOUTH INDIA amandaj. weidman O O M I CALCUTTA 2007 Contents Date: v-> First published by Duke University Press in 2006 List of Illustrations vii © 2006 Duke University Press This edition printed in arrangement with Duke University Press Acknowledgments ix For publication and sale in India, Bangladesh, Burma, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Note on Transliteration and Spelling xvii Nepal and Pakistan only Introduction l ISBN 81 7046 319 X 1. Gone Native?: Travels of Typset in Bembo by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. the Violin in South India 25 Book design by Amy Ruth Buchanan Cover design by Sunandini Banerjee 2. From the Palace to the Street: Staging "Classical" Music 59 Published by Naveen Kishore, Seagull Books Pvt Ltd 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700 017 3. Gender and the Politics of Voice ill Printed at Rockewel Offset 4. Can the Subaltern Sing?: Music, 55B Mirza Ghalib Street, Calcutta 700 016 Language, and the Politics of Voice 150 Exclusively distributed in India and South Asia by Cambridge University Press India Pvt Ltd 5. A Writing Lesson: Musicology Cambridge House, 4381/4 Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002 and the Birth of the Composer 192 Portions of Chapter 3 were previously published as "Gender and the politics of voice: Colonial 6. Fantastic Fidelities 245 modernity and classical music in South India," in Cultural Anthropology 18, no. 2 (2003): 194-232. © 2003 American Anthropological Association. Afterword: Modernity and the Voice 286 Portions of Chapter 4 were previously published as "Can the subaltern sing? Music, language, Notes 291 and the politics of voice in twentieth-century South India," in Indian Economic and Social History Review 42, no. -

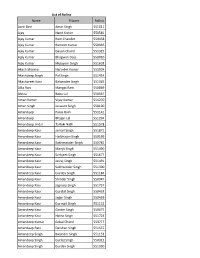

Name Fname Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor

List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor 550581 Ajay Kumar Ram Chander 550458 Ajay Kumar Ramesh Kumar 550336 Ajay Kumar Gayan Chand 551315 Ajay Kumar Bhagwan Dass 550010 Ajay Kumar Mulayam Singh 551603 Akash Sharma Narinder Kumar 551904 Akashdeep Singh Pal Singh 551414 Akashpreet Kaur Balwinder Singh 551365 Alka Rani Mangat Ram 550869 Alvina Babu Lal 550561 Aman Kumar Vijay Kumar 551270 Aman Singh Jaswant Singh 550190 Amandeep Paras Ram 551141 Amandeep Bhajan Lal 551294 Amandeep Jindal Tarloki Nath 551578 Amandeep Kaur Jarnail Singh 551871 Amandeep Kaur Harbhajan Singh 550169 Amandeep Kaur Sukhmander Singh 550781 Amandeep Kaur Manjit Singh 551490 Amandeep Kaur Sarbjeet Singh 551677 Amandeep Kaur Jasraj Singh 551491 Amandeep Kaur Sukhwinder Singh 551300 Amandeep Kaur Gurdev Singh 551184 Amandeep Kaur Shinder Singh 550347 Amandeep Kaur Jagroop Singh 551737 Amandeep Kaur Gurdial Singh 550453 Amandeep Kaur Jagsir Singh 550459 Amandeep Kaur Gurmail SIngh 551122 Amandeep Kaur Ginder Singh 550675 Amandeep Kaur Natha Singh 551724 Amandeep Kumar Gokal Chand 550777 Amandeep Rani Darshan Singh 551537 Amandeep Singh Baljinder Singh 551153 Amandeep Singh Gurtej Singh 550312 Amandeep Singh Gurdev Singh 551030 List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Amandeep Singh Balwinder SIngh 550016 Amandeep Singh Surjeet Singh 551251 Amandeep Singh Subhash Singh 551637 Amandeep Singh Angraj Singh 551622 Amandeep Singh Gurcharan Singh 551596 Amandeep Singh Nathu Ram 550748 Amandeep Singh Jarnail Singh 550058 Amandeep Singh Shinder -

Online Film Festival Raytoday by Films Division

A Report Films Division Govt. of India, Min. of I & B, 24- Dr. G Deshmukh Marg, Mumbai -26 Dated the 10th May, 2021 Online Film Festival RayToday by Films Division Satyajit Ray, one of the greatest film makers of all the time, is credited with taking Indian cinema to the global level. A true renaissance man, Ray earned worldwide fame for himself and to the art of cinema as well, with his poetic realism and cinematic imagination. Films Division marked beginning of the year-long birth centenary celebrations of the legendary filmmaker by screening Shyam Benegal’s eponymous biopic, Satyajit Ray on 2nd May 2021 on its website. Continuing with the celebrations of the auteur, Films Division has organized an online film festival, RayToday, a curated package of non-feature works by Ray along with films on him and his oeuvre, on FD website from 7th to 9th May 2021. RayToday included, among others, a rare documentary made by him on Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, the one and only television film by Ray on a short story by Munshi Premchand and the much acclaimed biopic by Shyam Benegal. The following films werestreamed in the festival : Sadgati (Satyajit Ray/Doordarshan/52 Mins/1981) - a television film set on rural India which throws light on caste system in society. Two (Satyajit Ray/Esso World Theatre/15 Mins/1964) - a simple but hard hitting societal commentary on the class struggle shows an encounter between a child of a rich family and a street child, and displays attempts of one-upmanship between kids in their successive display of toys. -

National Institute of Event Management

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EVENT MANAGEMENT ACADEMIC COLLABORATION CELEBRATING SEVENTEEN YEARS OF SERVICE TO THE EVENT INDUSTRY! “Genius without education and training is like gold in a mine.” - Anonymous We have centers at : We believe that creation and dissemination of knowledge is essential for any effective management. Our mission is to create future leaders, managers and professionals in the Global Event Management field by offering THE superior learning opportunities, engaging in research and scholarly activities along with a perfect blend of practical training on some of the most awesome and glittering sets of the worlds biggest events. We are guided by our commitment to achieve excellence in research and knowledge on event Academic Collaboration: management and promote entrepreneurial spirit SINGHANIA UNIVERSITY by encouraging the intellectual and diversified development of our faculty and students. Proud to be associated with : REGENCY INSTITUTE OF TAFE (AUSTRALIA) Through our distinctive curriculum and post AD CLUB OF BOMBAY graduate program we challenge the students to FEDERATION OF INDIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (FICCI) think and communicate and with a supportive ENTERTAINMENT & EVENT MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION (EEMA) climate of civility and freedom of expression our students become ethical, informed, wide CONFEDERATION OF INDIAN INDUSTRIES (CII) spectrum med and articulate participants in INDIAN ASSOCIATION OF AMUSEMENT PARKS AND INDUSTRIES (IAAPI) society. FERGUSSON COLLEGE, PUNE. • An entry into LIMCA BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS as Asia’s first & best event college. • Winner EEMAX GLOBAL Best Event Management Institute – Recognition by the event industry. • NIEM has produced the largest number of event professionals in the world. • NIEM has an excellent placement record.