Talk Derby to Me: Emergent Intellectual Property Norms Governing Roller Derby Pseudonyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2010

TUMBLEWEED CENTER FOR YOUTH DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2010 shared their collective knowledge of the community to select or- WELCOME ganizations that could make a difference immediately and without Dear Friends of Tumbleweed, any time-consuming application processes. Fundraising remained As Tumbleweed Center for Youth Development completes our 35th down only slightly, and was supported by many corporate grants year of providing a safety net for the at-risk, runaway, and home- such as Scottsdale Insurance’s parent company Nationwide Insur- less youth in our Community, we celebrate one of our most inspi- ance Co providing a significant grant for the first time. Certainly rational years amidst a host of challenges presented by a daunting many other gifts and grants were received from caregivers like you, financial climate. to make this turnaround possible. Like everyone else in Arizona we have watched as the economy Through all these challenges our employees continued to serve continued to spin into a state of emergency. We had made all the 47% more than last year, and still assisted youth in accomplish- adjustments to programs that could be made and finally more seri- ing wonderful outcomes. If you visit with a former Tumbleweed ous measures were required. Benefits were reduced, positions were Client, like the five (5) featured on the video during our Annual eliminated and we reduced an already thin management support Dinner Auction this year, you quickly understand the value of structure to historical low levels of 6% of our operating budget for Tumbleweed to the Community. Youth will tell you they were on a “general and administrative” and 4% for fundraising, down from path to self-destruction and became healthy productive members 10% & 5% respectively the previous year. -

Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’S Global Sport Institute

Devoney Looser, Foundation Professor of English Department of English, Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-1401 [email protected] Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’s Global Sport Institute SUMMARY Is roller derby a sport? Okay, sure, but, “Is it a legitimate sport?” No matter how you’re disposed to answer these questions, chances are that you’re asking without a firm grasp of roller derby’s past or present. Knowledge of both is crucial to understanding, or predicting, what derby’s future might look like in Sport 2036. From its official origins in Chicago in 1935, to its rebirth in Austin, TX in 2001, roller derby has been an outlier sport in ways admirable and not. It has long been ahead of the curve on diversity and inclusivity, a little-known fact. Even players and fans who are diehard devotees—who live and breathe by derby—have little knowledge of how the sport began, how it was different, or why knowing all of that might matter. In this paper, which is part of a book-in-progress, I offer a sense of the following: 1) why roller derby’s past and present, especially its unusual origins, its envelope-pushing play and players, and its waxing and waning popularity, matters to its future; 2) how roller derby’s cultural reputation (which grew out of roller skating’s reputation) has had an impact on its status as an American sport; 3) how roller derby’s economic history, from family business to skater-owned-and- operated non-profits, has shaped opportunity and growth; and 4) why the sport’s past, present, and future inclusivity, diversity, and counter-cultural aspects resonate so deeply with those who play and watch. -

The Unladylike Ladies of Roller Derby?: How Spectators, Players and Derby Wives Do and Redo Gender and Heteronormativity in All-Female Roller Derby

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online The Unladylike Ladies of Roller Derby?: How Spectators, Players and Derby Wives Do and Redo Gender and Heteronormativity in All-Female Roller Derby Megan Geneva Murray PhD The University of York Women’s Studies January 2012 Abstract All-female roller derby is a rapidly growing full-contact sport played on quad roller skates, with a highly popularized punk, feminine, sexual and tough aesthetic. Utilising theories on the institution of heterosexuality, I conducted a qualitative study on all-female roller derby which evaluated the way in which derby aligns with or challenges heteronormativity. In order to approach this question, I analysed, firstly, thirty-eight interviews with spectators, and twelve with players about their interactions with spectators. Secondly, I interviewed twenty-six players about the phenomenon of “derby wives,” a term used to describe particular female friendships in roller derby. My findings relate the complex relationship between players and spectators by focusing on: (i) spectators’ interpretations of the dress, pseudonyms, and identities of players, as well as the ways in which they were actively involved in doing gender through their discussions of all-female, coed, and all-male roller derby; (ii) players’ descriptions of their interactions with spectators, family members, romantic partners, friends and strangers, regarding roller derby. Additionally, I address the reformulation of the role “wife” to meet the needs of female players within the community, and “derby wives” as an example of Adrienne Rich’s (1980) “lesbian continuum.” “Derby girls” are described as “super heroes” and “rock stars.” Their pseudonyms are believed to help them “transform” once they take to the track. -

Degenderettes Protest Artwork Exhibiton Label Text

Degenderettes Antifa Art Exhibition Label Text Degenderettes Protest Artwork “Tolerance is not a moral absolute; it is a peace treaty.” Yonatan Zunger wrote these words in the weeks leading up to the first Women’s March in 2017. In the same article he suggested that the limits of tolerance could best be illustrated by a Degenderette standing defiantly and without aggression, pride bat in hand. Throughout this exhibit you will see artifacts of that defiance, some more visceral or confrontational than others, but all with the same message. Transgender people exist and we are a part of society’s peace treaty—but we are also counting the bodies (at least seven transgender people have been killed in the United States since the beginning of 2018). We Degenderettes are present at shows of solidarity such as the Trans March, Dyke March, Women’s March, and Pride. We endeavor to provide protection for transgender people at rallies and marches in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. We show up in opposition to people who seek to harm the transgender community—people like Milo Yiannopoulos, whose track record of outing transgender students and doxing immigrants inspired a contingent of Degenderettes to protest his fateful visit to U.C. Berkeley in February 2017. It was in the wake of the confrontation at U.C. Berkeley that shields were identified as weapons by the Berkeley Police Department and banned from all subsequent protests in the city. These guidelines have been adopted throughout the rest of the Bay Area. To us, the shields and everything else in this exhibit are still a type of armor. -

Welcom Packet CC18

WISHING YOU LUCK! WELCOME TEAMS We are very excited to have you in The Lone Star State and are looking forward to a highly competitive 9th annual Clover Cup Tournament. In this packet, please find included tournament information, hotel accommodations, transportation, local restaurant guide, and other information to help make your stay here in the DFW Metroplex a fun one! #WishingYouLuck #CloverCup2018 PARTICIPATING TEAMS: Mad Rollin Dolls Rocky Mountain RollerGirls Dallas Derby Devils @madrollindolls @RockyMountainRG @DDDevils Madison, WI Denver, CO Dallas, TX Houston Roller Derby OK Victory Dolls CharmCityRollerGirls @HouRollerDerby @okvictorydolls @ccrg Houston, TX Oklahoma City, OK Baltimore, MD Calgary Roller Derby SacramentoRollerDerby @CGYROLLERDERBY @SacRollerDerby Calgary, Alberta, CA Sacramento, CA CloverCup.com | derbydevils.com | facebook.com/derbydevils | instagram.com/dallasderbydevils Travel The Dallas Metro area has two major airports: Dallas Love Field Airport DFW International Airport 8008 Herb Kelleher Way, Dallas, TX 75235 2400 Aviation Drive, DFW Airport, TX 75261 www.dallas-lovefield.com www.dfwairport.com (214) 670-LOVE (972) 973-3112 Distance: ~22 Miles from Host Hotel Distance: ~13.5 Miles from Host Hotel Hotels Both hotels are about 2 1⁄2 miles from the tournament venue. We have secured a block of rooms and suites at two adjacent, affiliated hotels: Hampton Inn & Suites and Holiday Inn Express. Both standard rooms and suites are furnished with two queen beds. The rate for standard room is $109/night and for suite -

2019 International WFTDA Playoffs: Winston-Salem Bracket

ELIMINATION BRACKET 2x4 Roller Derby SEED #4 204 Paris Rollergirls GAME 5 2x4 Roller Derby SEED #12 145 FRIDAY 6:30 PM 58 GAME 1 64 FRIDAY 10 AM Paris Rollergirls SEED #5 142 GAME 11 SATURDAY 6:30 PM Santa Cruz Derby Girls Texas Rollergirls SEED #1 167 Texas Rollergirls Atlanta Roller Derby GAME 6 143 73 SEED #9 188 FRIDAY 8:30 PM Texas Rollergirls GAME 2 96 FRIDAY 12 PM Atlanta Roller Derby Angel City Derby 1ST PLACE SEED #8 89 GAME 16 SUNDAY 5:30 PM Bay Area Derby Texas Rollergirls Rainy City Roller Derby 2ND PLACE SEED #3 145 Helsinki Roller Derby GAME 7 Rainy City Roller Derby SATURDAY 10 AM SEED #6 217 106 120 2x4 Roller Derby 3RD PLACE GAME 3 126 Angel City Derby FRIDAY 2 PM Helsinki Roller Derby 2x4 Roller Derby Rainy City Roller Derby SEED #11 66 GAME 12 LOSER GAME 11 172 4TH PLACE SATURDAY 8:30 PM Lomme Roller Girls GAME 15 Angel City Derby SUNDAY 3 PM LOSER GAME 12 109 SEED #2 268 Rainy City Roller Derby Windy City Rollers GAME 8 162 SEED #7 126 SATURDAY 12 PM Angel City Derby Bay Area Derby LOSER GAME 2 222 76 GAME 4 Bay Area Derby FRIDAY 4 PM GAME 9 Bear City Roller Derby Lomme Roller Girls SATURDAY 2 PM SEED #10 168 LOSER GAME 3 79 Bear City Roller Derby Santa Cruz Derby Girls LOSER GAME 1 134 GAME 10 Santa Cruz Derby Girls Windy City Rollers SATURDAY 4 PM LOSER GAME 4 118 Atlanta Roller Derby LOSER GAME 6 155 CONSOLATION GAME 13 Helsinki Roller Derby 2019 International Helsinki Roller Derby SUNDAY 11 AM WFTDA PLAYOFFS GAMES LOSER GAME 7 179 Paris Rollergirls FRIDAY•SATURDAY•SUNDAY LOSER GAME 5 118 September 6-8 GAME 14 Bear City Roller Derby Bear City Roller Derby SUNDAY 1 PM hosted by Greensboro Roller Derby LOSER GAME 8 123 WFTDA.com/Winston-Salem All game times in Eastern Daylight Time.. -

Contesting and Constructing Gender, Sexuality, and Identity in Women's Roller Derby

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2018 Contesting and Constructing Gender, Sexuality, and Identity in Women's Roller Derby Suzanne Becker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Repository Citation Becker, Suzanne, "Contesting and Constructing Gender, Sexuality, and Identity in Women's Roller Derby" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3215. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/13568377 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTESTING AND CONSTRUCTING GENDER, SEXUALITY, AND IDENTITY IN WOMEN’S ROLLER DERBY By Suzanne R. Becker Bachelor of Arts – Journalism University of Wisconsin, Madison 1992 Master of Arts – Sociology University of Colorado, Colorado Springs 2004 Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2009 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy – Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2018 Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas April 25, 2017 This dissertation prepared by Suzanne R. -

Here Type Or Print Name and Title MARK D

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2018 ▶ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2018, and ending , 20 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization UNITED WAY WORLDWIDE D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 13-1635294 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 701 NORTH FAIRFAX STREET (703) 836-7100 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return ALEXANDRIA, VA 22314 G Gross receipts $ 268,002,921 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: BRIAN A. GALLAGHER H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: ✔ 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ◀ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: ▶ WWW.UNITEDWAY.ORG H(c) Group exemption number ▶ K Form of organization: ✔ Corporation Trust Association Other ▶ L Year of formation: 1932 M State of legal domicile: NY Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: TO IMPROVE LIVES BY MOBILIZING THE CARING POWER OF COMMUNITIES AROUND THE WORLD TO ADVANCE THE COMMON GOOD. -

2018 International WFTDA Championships Program

FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 9:00 AM DOORS OPEN 9:00 AM RDWS Outreach Event 10:00 AM SCRIMMAGE 10:00 AM GAME 1 12:00 PM GAME 7 2:00 PM GAME 12 | 3RD PLACE Crime City Rollers v Loser Game 1 v Loser Game 10 v Montréal Roller Derby Loser Game 2 Loser Game 11 12:00 PM GAME 2 2:00 PM GAME 8 4:00 PM GAME 13 | CHAMPS Jacksonville Roller Derby v Loser Game 3 v Winner Game 10 v Angel City Derby Loser Game 4 Winner Game 11 2:00 PM GAME 3 4:00 PM GAME 9 6:00 PM AWARDS CEREMONY Gotham Girls Roller Derby v Loser Game 5 v Texas Rollergirls Loser Game 6 4:00 PM GAME 4 6:00 PM GAME 10 Denver Roller Derby v Winner Game 3 v Arch Rival Roller Derby Winner Game 5 6:00 PM GAME 5 8:00 PM GAME 11 Rose City Rollers v Winner Game 4 v Winner Game 1 Winner Game 6 8:00 PM GAME 6 Victorian Roller Derby League v Winner Game 2 Charging blocker Cut Illegal procedure Low Block Out of Play (Block Lobster) (Juana Teaze) (Winters) (Boo Gogi) (Red Raven) 1352 2 20 215 255 Insubordination Cut Track Misconduct (Death Down Under) Alkali Mettle Soledad (Crackher Jack) (Rachel Rotten) 28 281 3 39 507 Back Block Darby Dagger procedimiento ilegal Polly Punchkin High Block (Pearl Jam) 5150 (Fischer) 612 (Volcanic Smash) 512 521 65 Pack Destruction Gross Misconduct Octane Jane Multiplayer Block West (Psycho) (Tui Lyon) 94 (Mallie Webster) 664 88 98 99 Ms. -

2018 International WFTDA Playoffs: Atlanta Program

FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 9:00 AM DOORS OPEN 9:00 AM DOORS OPEN 10:00 AM DOORS OPEN 10:00 AM GAME 1 10:00 AM GAME 7 11:00 AM GAME 13 Bear City Roller Derby (#12) v Jacksonville Roller Derby (#3) v Loser Game 5 v London Rollergirls (#5) Winner Game 4 Loser Game 7 12:00 PM GAME 2 12:00 PM GAME 8 1:00 PM GAME 14 Windy City Rollers (#9) v Montréal Roller Derby (#2) v Loser Game 6 v Rat City Roller Derby (#8) Winner Game 3 Loser Game 8 2:00 PM GAME 3 2:00 PM GAME 9 3:00 PM GAME 15 | 3RD PLACE Bay Area Derby (#7) v Loser Game 2 v Loser Game 11 v Queen City Roller Girls (#10) Loser Game 4 Loser Game 12 4:00 PM GAME 4 4:00 PM GAME 10 5:20 PM GAME 16 | CHAMPION Sun State Roller Derby (#6) v Loser Game 1 v Winner Game 11 v Ann Arbor Derby Dimes (#11) Loser Game 3 Winner Game 12 6:00 PM GAME 5 6:00 PM GAME 11 7:00 PM AWARDS CEREMONY Texas Rollergirls (#1) v Winner Game 5 v Winner Game 2 Winner Game 6 8:20 PM GAME 6 8:20 PM GAME 12 Atlanta Rollergirls (#4) v Winner Game 7 v Winner Game 1 Winner Game 8 BENCH COACH BENCH STAFF BENCH STAFF lethal emma pistol kandy C 811 - terror misu 62 - Fracture Mechanics 31 - the Hammer 14 - sonnet boom 1111 - Lezzie Arnaz C 84 - dr. -

When Leisure Becomes Work in Modern Roller Derby

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 Turning Passion Into Profit: When Leisure Becomes Work In Modern Roller Derby Amanda Nicole Draft Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Draft, Amanda Nicole, "Turning Passion Into Profit: When Leisure Becomes Work In Modern Roller Derby" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2202. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2202 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. TURNING PASSION INTO PROFIT: WHEN LEISURE BECOMES WORK IN MODERN ROLLER DERBY by AMANDA DRAFT DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 SOCIOLOGY Approved By: ________________________________________ Advisor Date ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ DEDICATION For past, present, and future roller derby enthusiasts. This work is for us, about us, by us. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest thanks first go to my advisor, Heather Dillaway, and the members of my dissertation committee: Krista Brumley, Sara Flory, and Heidi Gottfried. Thank you for bearing with me as I struggled to keep myself on track to complete this mountain of work and for reminding me that a dissertation does not have to be perfect, it just has to be done! Thank you for believing in my work and for pushing me to think of how my findings mattered to the world outside of derby, because sometimes I forget that there is such a world. -

Digital Program

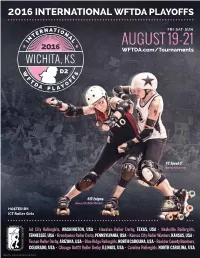

2016 INTERNATIONAL WFTDA PLAYOFFS N AT I FRI•SAT•SUN E R O N T A N L I AUGUST 19-21 WFTDA.com/Tournaments WICHITA, KS W S F F T F D O A P L A Y #3 Speed O' Houston Roller Derby #10 Enigma Kansas City Roller Warriors HOSTED BY: ICT Roller Girls Jet City Rollergirls, WASHINGTON, USA • Houston Roller Derby, TEXAS, USA • Nashville Rollergirls, TENNESSEE, USA • Brandywine Roller Derby, PENNSYLVANIA, USA • Kansas City Roller Warriors, KANSAS, USA • Tucson Roller Derby, ARIZONA, USA • Blue Ridge Rollergirls, NORTH CAROLINA, USA • Boulder County Bombers, COLORADO, USA • Chicago Outfit Roller Derby, ILLINOIS, USA • Carolina Rollergirls, NORTH CAROLINA, USA PHOTO: DANFORTH JOHNSON ADS/COPY N AT I O E R N T A N L I nothing TO BEING THERE W S F compares T T N D E A M TO U R N A WELCOME 2016 WFTDA DIVISION 2 PLAYOFFS On behalf of the WFTDA Board of Directors, Officers, and staff, I am excited to welcome you to the 2016 International WFTDA Division 2 Playoffs. Nothing compares to being here. Plain and simple. The fantastic feats of athleticism on the track, the excitement and emotion in the stands, the concentration and attention to detail on the dais, and the enticing goods in the vendor village. This is roller derby. We are roller derby. So who will you be today? Will you be persistent and powerful, strong and swift, a leader on the track? Will you be fierce and fast and forceful, a goal setter…a record breaker? Will you be focused and creative? Will you capture that amazing shot? Will you paint your face and put on your colors? Will you chant and sing and cry and scream? One thing is clear—whether you’re a Skater, Official, photographer, announcer, or fan (or any combination thereof), TODAY YOU WILL BE ROLLER DERBY! This weekend wouldn’t be possible without the tremendous amount of support and time our hosts, ICT Roller Girls, and all of their volunteers have put in.