When Leisure Becomes Work in Modern Roller Derby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatre Reviews

REVIEWERS Imke Lichterfeld, Erica Sheen INITIATING EDITOR Mateusz Grabowski TECHNICAL EDITOR Zdzisław Gralka PROOF-READER Nicole Fayard COVER Alicja Habisiak Task: Increasing the participation of foreign reviewers in assessing articles approved for publication in the semi-annual journal Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance financed through contract no. 605/P-DUN/2019 from the funds of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education devoted to the promotion of scholarship Printed directly from camera-ready materials provided to the Łódź University Press © Copyright by Authors, Łódź 2019 © Copyright for this edition by University of Łódź, Łódź 2019 Published by Łódź University Press First Edition W.09355.19.0.C Printing sheets 12.0 ISSN 2083-8530 Łódź University Press 90-131 Łódź, Lindleya 8 www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] phone (42) 665 58 63 Contents Contributors ................................................................................................... 5 Nicole Fayard, Introduction: Shakespeare and/in Europe: Connecting Voices ................................................................................................ 9 Articles Nicole Fayard, Je suis Shakespeare: The Making of Shared Identities in France and Europe in Crisis .......................................................... 31 Jami Rogers, Cross-Cultural Casting in Britain: The Path to Inclusion, 1972-2012 .......................................................................................... 55 Robert -

Ford Guilty of Murder, Arson

1A SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Championships Girl Scouts launch SUNDAY EDITION at stake in hoops ‘MEdia’ column in for Tigers, Indians. 1B Lake City Reporter. 1D Ford guilty of murder, arson shared with Kristy L. Whatley. A Columbia verdict shortly after 7 p.m. man who admitted to law enforcement Faces possible life term County jury convicted Ford of first-degree The trial lasted five days. he poured gasoline on the couch and lit for starting house fire that arson, as well. The jury heard from 20 it. Prosecutors say he escaped south on Ford faces a maximum penalty of life witnesses, including tool- Interstate 75 through a hole he cut in a killed girlfriend in 2009. in prison for second-degree murder, with mark experts, the state fence on the property. The mobile home a minimum sentence of 25 years. Second- fire marshal and Whatley’s Whatley and Ford shared for about one By DEREK GILLIAM degree arson carries a maximum sentence family members, includ- and a half years was off Lake Jeffery Road [email protected] of 30 years in prison. Ford, 46, will be Ford ing Whatley’s mother and and bordered I-75. sentenced on Feb. 27 at 1:30 p.m. in the sister. Getzan argued cutting the hole in the Kenneth Allen Ford was found guilty Columbia County Courthouse. Roberta Getzan, assistant state attor- fence proved premeditation, and the jury Friday of second-degree murder for start- The jury deliberated for about seven ney, began closing statements at 9 a.m. -

Lasvegasadvisor Issue 3

$5 ANTHONY CURTIS’ March 2018 Vol. 35 LasVegasAdvisor Issue 3 INFERNO AT PARIS It’s on fire … pg. 8 WYNN (LESS) RESORTS What’s next? … pg. 1 THE NEW TAX LAW How does it affect gamblers? … pg. 3 EATING LAS VEGAS ON THE CHEAP 25 top restaurants with bargain pricing … pg. 4 TWO INSTA- COMPS Play … Eat … pgs. 8, 11 CASINOS Local (702) Toll Free • 2018 LVA MEMBER REWARDS • Numbers (800) († 855) (††866) (* 877) (**888) Local Toll Free ALL-PURPOSE COMP DRINKS Aliante Casino+Hotel+Spa ........692-7777 ............477-7627* †† 50% off up to $50 (Palms) Free Drink Brewers, Kixx, or Havana Bar (Boulder Station); 3 Free Aria ............................................590-7111 ............359-7757 Rounds (Ellis Island); Free Margarita or Beer (Fiesta Rancho); Free Mar- Arizona Charlie’s Boulder ..........951-5800 ............362-4040 ACCOMMODATIONS Arizona Charlie’s Decatur ..........258-5200 ............342-2695 garita (Sunset Station) Bally’s ........................................739-4111 ............603-4390* 2-For-1 Room (El Cortez) Bellagio ......................................693-7111 ............987-7111** SHOWS Binion’s ......................................382-1600 ............937-6537 BUFFETS 2-For-1 Hypnosis Unleashed (Binion’s), Show in the Cabaret (Westgate Boulder Station ..........................432-7777 ............683-7777 2-For-1 Buffet (Aliante Casino+Hotel, Arizona Charlie’s Boulder, Arizona Las Vegas); 2-For-1 or 50% off Beatleshow (Saxe Theater), Nathan Bur- Caesars Palace..........................731-7110 ............227-5938†† -

Recognised English and UK Ngbs

MASTER LIST – updated August 2014 Sporting Activities and Governing Bodies Recognised by the Sports Councils Notes: 1. Sporting activities with integrated disability in red 2. Sporting activities with no governing body in blue ACTIVITY DISCIPLINES NORTHERN IRELAND SCOTLAND ENGLAND WALES UK/GB AIKIDO Northern Ireland Aikido Association British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board AIR SPORTS Flying Ulster Flying Club Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Aerobatic flying British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association Royal Aero Club of UK Aero model Flying NI Association of Aeromodellers Scottish Aeromodelling Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association Ballooning British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club Gliding Ulster Gliding Club British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association Hang/ Ulster Hang Gliding and Paragliding Club British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association Paragliding Microlight British Microlight Aircraft Association British Microlight Aircraft Association -

Annual Report 2010

TUMBLEWEED CENTER FOR YOUTH DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2010 shared their collective knowledge of the community to select or- WELCOME ganizations that could make a difference immediately and without Dear Friends of Tumbleweed, any time-consuming application processes. Fundraising remained As Tumbleweed Center for Youth Development completes our 35th down only slightly, and was supported by many corporate grants year of providing a safety net for the at-risk, runaway, and home- such as Scottsdale Insurance’s parent company Nationwide Insur- less youth in our Community, we celebrate one of our most inspi- ance Co providing a significant grant for the first time. Certainly rational years amidst a host of challenges presented by a daunting many other gifts and grants were received from caregivers like you, financial climate. to make this turnaround possible. Like everyone else in Arizona we have watched as the economy Through all these challenges our employees continued to serve continued to spin into a state of emergency. We had made all the 47% more than last year, and still assisted youth in accomplish- adjustments to programs that could be made and finally more seri- ing wonderful outcomes. If you visit with a former Tumbleweed ous measures were required. Benefits were reduced, positions were Client, like the five (5) featured on the video during our Annual eliminated and we reduced an already thin management support Dinner Auction this year, you quickly understand the value of structure to historical low levels of 6% of our operating budget for Tumbleweed to the Community. Youth will tell you they were on a “general and administrative” and 4% for fundraising, down from path to self-destruction and became healthy productive members 10% & 5% respectively the previous year. -

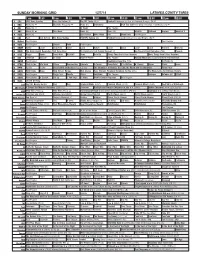

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’S Global Sport Institute

Devoney Looser, Foundation Professor of English Department of English, Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-1401 [email protected] Roller Derby: Past, Present, Future RESEARCH PAPER for ASU’s Global Sport Institute SUMMARY Is roller derby a sport? Okay, sure, but, “Is it a legitimate sport?” No matter how you’re disposed to answer these questions, chances are that you’re asking without a firm grasp of roller derby’s past or present. Knowledge of both is crucial to understanding, or predicting, what derby’s future might look like in Sport 2036. From its official origins in Chicago in 1935, to its rebirth in Austin, TX in 2001, roller derby has been an outlier sport in ways admirable and not. It has long been ahead of the curve on diversity and inclusivity, a little-known fact. Even players and fans who are diehard devotees—who live and breathe by derby—have little knowledge of how the sport began, how it was different, or why knowing all of that might matter. In this paper, which is part of a book-in-progress, I offer a sense of the following: 1) why roller derby’s past and present, especially its unusual origins, its envelope-pushing play and players, and its waxing and waning popularity, matters to its future; 2) how roller derby’s cultural reputation (which grew out of roller skating’s reputation) has had an impact on its status as an American sport; 3) how roller derby’s economic history, from family business to skater-owned-and- operated non-profits, has shaped opportunity and growth; and 4) why the sport’s past, present, and future inclusivity, diversity, and counter-cultural aspects resonate so deeply with those who play and watch. -

MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS and HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 Sportbusiness Group All Rights Reserved

THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 SportBusiness Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. The information contained in this publication is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. While care has been taken to ensure that the information is accurate, the publishers can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions or for changes to the details given. Readers are cautioned that forward-looking statements including forecasts are not guarantees of future performance or results and involve risks and uncertainties that cannot be predicted or quantified and, consequently, the actual performance of companies mentioned in this report and the industry as a whole may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Author: David Walmsley Publisher: Philip Savage Cover design: Character Design Images: Getty Images Typesetting: Character Design Production: Craig Young Published by SportBusiness Group SportBusiness Group is a trading name of SBG Companies Ltd a wholly- owned subsidiary of Electric Word plc Registered office: 33-41 Dallington Street, London EC1V 0BB Tel. +44 (0)207 954 3515 Fax. +44 (0)207 954 3511 Registered number: 3934419 THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Author: David Walmsley THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS -

MARCH for PARKS Festival? on March of Possessing Firearms 15, 16, and 17

The Nashville News THURSDAY • March 14, 2013 • Issue 21 • 1 Section • 14 Pages • In Howard County, Arkansas since 1878 • USPS 371-540 • 75 cents IN BRIEFt Local rap artists to give back to Jonquil the community with concert Fest is this TERRICA HENDRIX tween two Howard County weekend Editor organizations. “Fifty percent of the proceeds go to Howard Jonquils NASHVILLE – Local rap artists County Single Parent Scholar- are in bloom Makwan Scroggins, Charles Vaughn ship Fund and 50 percent goes at Historic II, Maverick Canady and Urian to [the] New Addition Neighbor- Washington “Swang” Henry will be some of the hood Development Corporation State Park. The featured acts for the “Giving Back (NANDC).” arrival of those to the Community” concert set for eye-catching The Rev. Willie Benson Jr., flowers signi- Saturday. founder of NANDC, will be open- fies that it’s Gynder Benson, an organizer of ing the event up with a prayer. time to pull out the concert, said proceeds from the The concert will be held at all the stops fund raiser concert will be split be- See CONCERT / Page 4 and celebrate the arrival of Spring, and what better way to do that than to visit the 45th Howard Co. man accused Annual Jonquil MARCH FOR PARKS Festival? On March of possessing firearms 15, 16, and 17. Historic Washington will after being diagnosed welcome craft vendors from with a mental illness the surround- ing regions as TEXARKANA - A Howard Craven ordered Leslie they bring their goods to one County man is facing fed- detained, citing a need to central loca- eral firearms charges for protect the community and tion and make allegedly possessing guns Leslie himself, court docu- it easy to shop after being diagnosed with ments state. -

Prince Saud Is Mourned

VOL XXXVIII No. 112 (GGDN 024) FRIDAY, 10th JULY 2015 200 Fils/2 Riyals ABC Ad new QRcode 6cm x 4col.pdf 1 2/19/15 3:48 PM Visit us at www.gdnonline.com WhatsApp us on 39451177 Millions hit Basma Ad.indd4m 1 have7/8/15 4:13 PM by London ed Syria Tube strike says UN 14 15 King hails spirit of unity MANAMA: Difficult times can always be over- the royal directives, support of the government come by reinforcing cohesion and social unity, led by His Royal Highness Prime Minister His Majesty King Hamad said last night. Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa and fol- He was speaking as he received, at the low-up of His Royal Highness Prince Salman Muharraq Sports Club, Ramadan well-wishers. bin Hamad Al Khalifa, Crown Prince, Deputy The visit was part of the King’s meetings with Supreme Commander and First Deputy Premier. citizens of Bahrain. Dr Al Mudhahka welcomed the royal reforms He ordered that a multi-purpose hall be built and decisions made aimed at protecting the for the benefit of Muharraq citizens. homeland and citizens. His Majesty exchanged Ramadan greetings The King was presented with commemorative with the well-wishers. gifts by Muharraq Governor Salman Bin Hindi Dr Jawahir Shaheen Al Mudhahka, after recit- and Muharraq Sports Club chairman Shaikh ing verses from the Quran, hailed the develop- Ahmed bin Ali Al Khalifa. ment projects witnessed by Muharraq, thanks to More pictures – Page 2 n The King visits the Muharraq Sports Club Prince Saud is mourned RIYADH: Former Saudi Even before the 2011 MANAMA:RENTS Bahrain’s business- “This -

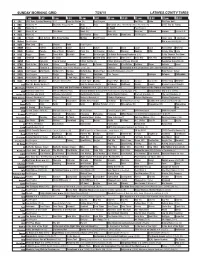

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse.