Volume 7, 1954

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2019 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2019 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 12 December 2019 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 314 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2019 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (transits 149 and 167). -

Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle by C.R

ARCTIC VOL. 67, NO. 2 (JUNE 2014) InfoNorth Five Hundred Meetings of the Arctic Circle by C.R. Burn HE ARCTIC CIRCLE, AN OPEN CLUB FOUNDED to bring during the talks and the meetings should therefore be together friends interested in all aspects of the moved! The Circle seems to be happy in its present accom- TNorth, celebrated its 500th meeting on 8 April 2014. modation at the location of the first meeting, where admit- The Circle, conceived on 30 October 1947, was the brain- tance restrictions have relaxed with the passage of time. In child of Graham and Diana Rowley and Tom and Jackie the first 10 years, only four of the speakers were women, Manning, who recognized the need in Ottawa for an infor- but in the last decade more than 20 women have held the mal but regular gathering of people interested in the Arc- floor. There were 79 meetings in 1947 – 58, of which 16 tic. At the time, these people were almost all working for covered government operations, 12 the natural sciences, departments and agencies of the federal government, but in 9 issues of development, and 13 human society. In the last an institution notorious for its silos, many were unaware of decade, although only 69 meetings have been held, the cor- each other’s work, interests, plans, and ideas. The Canadian responding numbers were 11, 29, 3, and 20, respectively. As Arctic had played but a small part in the Second World War, Northerners have assumed control of development within but it became a focus of much greater strategic concern dur- the territories, Ottawa’s role has diminished, and the range ing the Cold War, leading at first to military exercises and of interests active here in the South has shifted. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2020 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2020 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 7 April 2021 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 starting in the Pacific Ocean to reach the Atlantic Oceam, but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 319 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2020 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (marked ‘cp’). -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère. -

Why the St. Roch? Why the Northwest Passage? Why 1940?

ARCTIC VOL. 46, NO. 1 (MARCH 1903) P. 82-87 Why the St. Ruch? Why the Northwest Passage? Why 1940? New Answers to Old Questions For almost half a century, the reasons behind orders sending of the St. Roch to a government plan to defend and occupy the the RCMP schooner St. Roch through the Northwest Passage island in the spring of 1940 (Caulkin, 1940; Fripps, 1940). during the Second World War have puzzled historians and otherSubsequent evidence from Larsen’s personal papers confirms scholars. True, there wererumours of a defence-related mission, that the captain was fully aware of the original purpose of his but there was no hard evidence,no tangible proof. Nor did the mission (Larsen, 1957a,b). captain, Sgt. Henry Larsen, provide many clues other than Although these memos might appear to contradict Larsen’s “Canada was at war and the government had realized the needown explanation, careful study of the documents and related todemonstrate the country’s sovereignty over the Arctic circumstances suggests that the reference to sovereigntyin the islands” (Larsen, 1967), a statement not verified in official autobiography published posthumously could also be defined documents. Then unexpectedly last year, during research on in very broad terms to include security considerations. Omission Canadian wartime relations with Greenland,two memos were of any reference to the initial motive behind the orders was found in RCMP archival files that directly linked the voyage entirely in keeping with his responsibility as a memberof the The Sr. Roch moored to ice in the Western Arctic in the mid-1930s. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2016 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2016 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland revised 14 November 2016 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 255 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2016 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, from or to the Pacific Ocean (Bering Sea) through the Bering Strait. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the west coast of Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (transits 154 and 171). These are shown on the map following, and proceed as follows: 1: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Viscount Melville Sound, McClure Strait, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. -

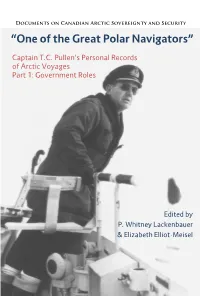

"One of the Great Polar Navigators": Captain T.C. Pullen's Personal

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security “One of the Great Polar Navigators” Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Part 1: Government Roles Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer & Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages, Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel DCASS Number 12, 2018 Cover: Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage, BIOG P: Pullen, Thomas Charles, file 2004/55, folder 1. Cover design: Whitney Lackenbauer Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2018 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. i Acronyms ............................................................................................................... xlv Part 1: H.M.C.S. -

The Photographic Archives of the Arctic Institute of North America

ARCTIC VOL. 57, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 2004) P. 317–324 InfoNorth The Photographic Archives of the Arctic Institute of North America by Constance Martin NE OF THE LEAST-KNOWN TANGIBLE ASSETS of the recognition that photographs are more than an accessory to Arctic Institute of North America (AINA) is its history’s written text. They are an essential element in the Ophotographic collection, which includes images very construction of that history, both written and oral. dating from the 1890s to the mid-twentieth century. These AINA’s collection of photographs is no exception. 4000 photographs—which reside, uncatalogued and rap- AINA proposes to make the collection widely available idly deteriorating, in two file cabinets—are a valuable by creating an electronic database. Each photograph will resource. The rich visual records contain important scien- be researched and scanned into the computer using the tific information on all aspects of the Arctic environment, University of Calgary’s InMagic database software. its geology, archaeology, geography, glaciology, and an- The potential for the collection is enormous. Made thropology, as well as information on Arctic exploration available to the indigenous peoples of the North, it will and the cultural life of the indigenous people. One example help them to recall their own history. It will present of the richness of AINA’s collection is the 142 photo- information of value to anthropologists, archaeologists, graphs donated by Walter Wood, scientist and explorer, professional historians, and scientists. Commercial and who was engaged in AINA’s Snow Cornice Project of academic publications needing visual material will also be 1948 and the Icefield Ranges Research Project in the St. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Following Section on Early History Was Written by Professor William (Bill) Barr, Arctic Historian, the Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary

The following section on early history was written by Professor William (Bill) Barr, Arctic Historian, The Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary. Prof. Barr has published numerous books and articles on the history of exploration of the Arctic. In 2006, William Barr received a Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to the recorded history of the Canadian North from the Canadian Historical Association. As well, Prof. Barr, a known admirer of Russian Arctic explorers, has been credited with making known to the wider public the exploits of Polar explorations by Russia and the Soviet Union. HISTORY OF ARCTIC SHIPPING UP UNTIL 1945 Northwest Passage The history of the search for a navigable Northwest Passage by ships of European nations is an extremely long one, starting as early as 1497. Initially the aim of the British and Dutch was to find a route to the Orient to grab their share of the lucrative trade with India, Southeast Asia and China, till then monopolized by Spain and Portugal which controlled the route via the Cape of Good Hope. In 1497 John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), sponsored by King Henry VII of England, sailed from Bristol in Mathew; he made a landfall variously identified as on the coast of Newfoundland or of Cape Breton, but came no closer to finding the Passage (Williamson 1962). Over the following decade or so, he was followed (unsuccessfully) by the Portuguese seafarers Gaspar Corte Real and his brother Miguel, and also by John Cabot’s brother Sebastian, who some theorize, penetrated Hudson Strait (Hoffman 1961). The first expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage that are definitely known to have reached the Arctic were those of the English captain, Martin Frobisher in 1576, 1577 and 1578 (Collinson 1867; Stefansson 1938). -

An Ill-Fated Journey by Lindsay Foss

Appendix : canadian geographic articles 4 ADAPTED FROM N An Ill-fated Journey by Lindsay Foss www.canadiangeographic.ca/specialfeatures/franklinexpedition/history4 n May 5, 1845, Sir John Franklin, an explorer and captain O of the Royal Navy, was given official instructions to go on a three-year expedition to locate the Northwest Passage, a route linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. On the morning of May 19, 1845, the from starvation and malnutrition. expedition consisting of two ships – the More recently, theories suggest the Terror and Erebus – sailed from Green- Franklin Expedition crew fell victim hithe, England, along with 129 men and to lead poisoning – nearly 8,000 tin enough provisions to last at least three cans, sealed with lead and filled with years. preserved meat, soup and vegetables, were aboard the ships. At the end of July 1845, the expedition met two whaling ships – the Prince of According to some, the rest of the crew Wales and the Enterprise – in Baffin Bay. abandoned the ships and trekked across It was the expedition’s last contact with the ice, towards King William Island. the outside world. None of the men survived the expedi- tion. Reports from the Inuit suggest During September 1846, the Terror and that crew died right there on the ice. Erebus became trapped in the Arctic ice in the Victoria Strait, forcing the end of Many questions surrounding the Frank- the expedition. lin Expedition remain unanswered. From this point, the details of the ex- Only a few facts remain: Franklin and pedition are scarce, leaving room for his two sea-faring vessels remain in myth and mystery. -

Canadian Icebreaking Capabilities Not up to Snuff, Experts

23 Policy Briefi ng Transportation shore of Quebec. The 600-person communi- ance multitask vessel, which is not capable require rescue by the Canadian Coast ty relies on a ferry service to provide them of handling the ice conditions in this area.” Guard’s icebreakers. According to Mr. Canadian with everything from groceries to propane. Of the four icebreakers delegated to Webb, Canada’s icebreaking capabilities “All our grocery stores rely on it for their the Atlantic region, only the Molly Kool are not entirely suffi cient for dealing with produce and product, all our restaurants. I was built in the 21st century. The ship was the current risks, let alone those future heat my business with propane, that has to initially launched in 2001, then purchased risks posed by a changing climate. Mr. icebreaking comes across on the ferry,” said L’Anse-au- by the federal government from Norway as Webb said that the six Arctic Offshore Pa- Loup Mayor Trent O’Brien. “During the win- part of the National Shipbuilding Strategy. trol vessels included in the National Ship- ter months, we have ice conditions. Usually It was one of three ships purchased from building Strategy are not equipped to serve capabilities by mid-February they’re very troublesome Norway for a total cost of $610-million. as icebreakers—their “ice-strengthened” for transportation. It prevents our ferry The ship was retrofi tted with icebreaking hulls can “barely deal with fi rst year ice,” he from crossing for days on end.” capabilities by the Davie shipyard, and fi rst said—and the single heavy icebreaker the As of Thursday, Feb.