Oppression Through Violence: the Case of Colombia - an Expansion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests

THE POSITION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TROPICAL FORESTS Gerard A. Persoon Tessa Minter Barbara Slee Clara van der Hammen Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2004 Gerard A. Persoon, Tessa Minter, Barbara Slee and Clara van der Hammen The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests (Tropenbos Series 23) Cover: Baduy (West-Java) planting rice ISBN 90-5113-073-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2004 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International. No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microfilm, and electromagnetic record without prior written permission. Photos: Gerard A. Persoon (cover and Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7), Carlos Rodríguez and Clara van der Hammen (Chapter 5) and Barbara Slee (Chapter 6) Layout: Blanca Méndez CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 1. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND NATURAL RESOURCE 3 MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL POLICY GUIDELINES 1.1 The International Labour Organization 3 1.1.1 Definitions 4 1.1.2 Indigenous peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 5 management 1.1.3 Resettlement 5 1.1.4 Free and prior informed consent 5 1.2 World Bank 6 1.2.1 Definitions 7 1.2.2 Indigenous Peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 7 management 1.2.3 Indigenous Peoples’ Development Plan and resettlement 8 1.3 UN Draft Declaration on the -

Deductions Suggested by the Geographcial Distribution of Some

Deductions suggested by the geographcial distribution of some post-Columbian words used by the Indians of S. America, by Erland Nordenskiöld. no.5 Nordenskiöld, Erland, 1877-1932. [Göteborg, Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag, 1922] http://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.32000000635047 Public Domain in the United States, Google-digitized http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-us-google This work is deemed to be in the public domain in the United States of America. It may not be in the public domain in other countries. Copies are provided as a preservation service. Particularly outside of the United States, persons receiving copies should make appropriate efforts to determine the copyright status of the work in their country and use the work accordingly. It is possible that heirs or the estate of the authors of individual portions of the work, such as illustrations, assert copyrights over these portions. Depending on the nature of subsequent use that is made, additional rights may need to be obtained independently of anything we can address. The digital images and OCR of this work were produced by Google, Inc. (indicated by a watermark on each page in the PageTurner). Google requests that the images and OCR not be re-hosted, redistributed or used commercially. The images are provided for educational, scholarly, non-commercial purposes. Generated for Eduardo Ribeiro (University of Chicago) on 2011-12-10 23:30 GMT / Public Domain in the United States, Google-digitized http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd-us-google Generated for Eduardo Ribeiro -

An Amerind Etymological Dictionary

An Amerind Etymological Dictionary c 2007 by Merritt Ruhlen ! Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greenberg, Joseph H. Ruhlen, Merritt An Amerind Etymological Dictionary Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Amerind Languages—Etymology—Classification. I. Title. P000.G0 2007 000!.012 00-00000 ISBN 0-0000-0000-0 (alk. paper) This book is dedicated to the Amerind people, the first Americans Preface The present volume is a revison, extension, and refinement of the ev- idence for the Amerind linguistic family that was initially offered in Greenberg (1987). This revision entails (1) the correction of a num- ber of forms, and the elimination of others, on the basis of criticism by specialists in various Amerind languages; (2) the consolidation of certain Amerind subgroup etymologies (given in Greenberg 1987) into Amerind etymologies; (3) the addition of many reconstructions from different levels of Amerind, based on a comprehensive database of all known reconstructions for Amerind subfamilies; and, finally, (4) the addition of a number of new Amerind etymologies presented here for the first time. I believe the present work represents an advance over the original, but it is at the same time simply one step forward on a project that will never be finished. M. R. September 2007 Contents Introduction 1 Dictionary 11 Maps 272 Classification of Amerind Languages 274 References 283 Semantic Index 296 Introduction This volume presents the lexical and grammatical evidence that defines the Amerind linguistic family. The evidence is presented in terms of 913 etymolo- gies, arranged alphabetically according to the English gloss. -

Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness

Colby Quarterly Volume 13 Issue 1 March Article 5 March 1977 The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness Edwin J. Kenney, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 13, no.1, March 1977, p.42-66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kenney, Jr.: The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn ofthe Century Consciousness by EDWIN J. KENNEY, JR. N THE YEARS 1923-24 Virginia Woolf was embroiled in an argument I with Arnold Bennett about the responsibility of the novelist and the future ofthe novel. In her famous essay "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown," she observed that "on or about December, 1910, human character changed";1 and she proceeded to argue, without specifying the causes or nature of that change, that because human character had changed the novel must change if it were to be a true representation of human life. Since that time the at once assertive and vague remark about 1910, isolated, has served as a convenient point of departure for historians now writing about the social and cultural changes occurring during the Edwardian period.2 Literary critics have taken the ideas about fiction from "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" and Woolfs other much-antholo gized essay "Modern Fiction" as a free-standing "aesthetic manifesto" of the new novel of sensibility;3 and those who have recorded and discussed the "whole contention" between Virginia Woolf and Arnold Bennett have regarded the relation between Woolfs historical observation and her ideas about the novel either as just a rhetorical strategy or a generational disguise for the expression of class bias against Bennett.4 Yet few readers have asked what Virginia Woolf might have nleant by her remark about 1910 and the novel, or what it might have meant to her. -

Not to Be Published in the Official Reports in The

Filed 11/8/05 P. v. Mendoza CA2/7 Opinion following rehearing NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL REPORTS California Rules of Court, rule 977(a), prohibits courts and parties from citing or relying on opinions not certified for publication or ordered published, except as specified by rule 977(b). This opinion has not been certified for publication or ordered published for purposes of rule 977. IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION SEVEN THE PEOPLE, B162636 Plaintiff and Respondent, (Los Angeles County Super. Ct. Nos. TA 062114, v. TA 063735) JOSE P. MENDOZA, et al., OPINION ON REHEARING Defendants and Appellants. In re ANTHONY J. CONTRERAS, B173722 (Los Angeles County on Habeas Corpus. Super. Ct. No. TA 062114) ORIGINAL PROCEEDING, application for writ of habeas corpus considered with appeals from judgments of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County. John S. Cheroske and Jack W. Morgan, Judges. Writ petition of Contreras granted. Judgment against Rivas reversed, and judgment against Mendoza affirmed as modified. Richard A. Levy, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jose Mendoza. Peter Gold, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jerry Rivas. C. Delaine Renard, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Anthony J. Contreras. Bill Lockyer, Attorney General, Robert R. Anderson, Chief Assistant Attorney General, Pamela C. Hamanaka, Senior Assistant Attorney General, Lance E. Winters, Richard Breen and Susan Sullivan Pithey, Deputy Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent. _________________________________ Defendants Jose Mendoza, Jerry Rivas and Anthony Contreras timely appealed from their convictions for first degree murder. -

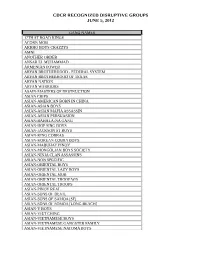

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

F E a T U R E S Summer 2021

FEATURES SUMMER 2021 NEW NEW NEW ACTION/ THRILLER NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW 7 BELOW A FISTFUL OF LEAD ADVERSE A group of strangers find themselves stranded after a tour bus Four of the West’s most infamous outlaws assemble to steal a In order to save his sister, a ride-share driver must infiltrate a accident and must ride out a foreboding storm in a house where huge stash of gold. Pursued by the town’s sheriff and his posse. dangerous crime syndicate. brutal murders occurred 100 years earlier. The wet and tired They hide out in the abandoned gold mine where they happen STARRING: Thomas Nicholas (American Pie), Academy Award™ group become targets of an unstoppable evil presence. across another gang of three, who themselves were planning to Nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler), Golden Globe Nominee STARRING: Val Kilmer (Batman Forever), Ving Rhames (Mission hit the very same bank! As tensions rise, things go from bad to Penelope Ann Miller (The Artist), Academy Award™ Nominee Impossible II), Luke Goss (Hellboy II), Bonnie Somerville (A Star worse as they realize they’ve been double crossed, but by who Sean Astin (The Lord of the Ring Trilogy), Golden Globe Nominee Is Born), Matt Barr (Hatfields & McCoys) and how? Lou Diamond Phillips (Courage Under Fire) DIRECTED BY: Kevin Carraway HD AVAILABLE DIRECTED BY: Brian Metcalf PRODUCED BY: Eric Fischer, Warren Ostergard and Terry Rindal USA DVD/VOD RELEASE 4DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCED BY: Brian Metcalf, Thomas Ian Nicholas HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE WESTERN/ ACTION, 86 Min, 2018 4K, HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE USA DVD RELEASE -

On the External Relations of Purepecha: an Investigation Into Classification, Contact and Patterns of Word Formation Kate Bellamy

On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Kate Bellamy To cite this version: Kate Bellamy. On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation. Linguistics. Leiden University, 2018. English. tel-03280941 HAL Id: tel-03280941 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03280941 Submitted on 7 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61624 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bellamy, K.R. Title: On the external relations of Purepecha : an investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Issue Date: 2018-04-26 On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Published by LOT Telephone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht Email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Kate Bellamy. ISBN: 978-94-6093-282-3 NUR 616 Copyright © 2018: Kate Bellamy. All rights reserved. On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation PROEFSCHRIFT te verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Noticia Mercantil Febrero De 2012

Noticia Mercantil Febrero de 2012 INSCRIPCIONES EN EL REGISTRO MERCANTIL LICENCIA 002121 DEL MINGOBIERNO TARIFA REDUCIDA A LA ADPOSTAL PUBLICACIÓN DE RENOVACIONES Matrícula O.J. RAZON SOCIAL FECHA RENOVACION 38067 1 MARQUEZ RAMIREZ LUIS ALBERTO 01/02/2012 38068 2 MADERAS MARQUEZ 01/02/2012 52289 1 LEAL SALCEDO FERNANDO ANTONIO 01/02/2012 68450 1 MAYORGA CUERVO JOSE LUIS 01/02/2012 68451 2 ALMACEN REAL DE VIDRIOS 01/02/2012 71531 1 ORTEGA LAGOS JESUS ESTEBAN 01/02/2012 71532 2 CONFECCIONES MICHEL'S SPORT 01/02/2012 78293 1 CONTRERAS SALAMANCA IVAN ENRIQUE 01/02/2012 78294 2 COMERCIALIZADORA IVENCOS 01/02/2012 79174 1 CARRENO NUNEZ MARIO 01/02/2012 79175 2 VARIHERRAJES LEMAR 01/02/2012 86568 1 REYES LAZARO ARGEMIRO 01/02/2012 86569 2 ELECTRICOS ARGEMIRO 01/02/2012 88579 1 BLANCO DELGADO MARTHA DORIS 01/02/2012 88580 2 LA CASA DEL DAEWOO 01/02/2012 89577 1 CARVAJALINO ZAMBRANO MARILUZ 01/02/2012 90260 1 VARGAS DIAZ AMBROSIO 01/02/2012 90261 2 VIDRIERIA IMPERIAL DEL NORTE 01/02/2012 94260 1 GARCIA RANGEL MANUEL SILVESTRE 01/02/2012 94261 2 PRODUCCIONES MAGAR 01/02/2012 95448 1 LOPEZ ARISTIZABAL JESUS ABAD 01/02/2012 95449 2 COMERCIAL EL TRIUNFO DE ALEJANDRIA 01/02/2012 100567 3 DROGUERIA BIOSANAR CUCUTA LIMITADA 01/02/2012 102596 1 ORTEGA TORRES TOBIAS 01/02/2012 102597 2 CREACIONES NAYKER SPORT 01/02/2012 104698 1 BECERRA MORA WILSON 01/02/2012 104699 2 VARIEDADES VIANEY DE PUERTO STANDER 01/02/2012 105090 1 MORA ANGARITA EDGAR HENDERSON 01/02/2012 105091 2 EDGAR'S COMPUTER 01/02/2012 105514 1 MORA VILLAMIZAR ALFONSO MARIA 01/02/2012 105515 -

Colombia Curriculum Guide 090916.Pmd

National Geographic describes Colombia as South America’s sleeping giant, awakening to its vast potential. “The Door of the Americas” offers guests a cornucopia of natural wonders alongside sleepy, authentic villages and vibrant, progressive cities. The diverse, tropical country of Colombia is a place where tourism is now booming, and the turmoil and unrest of guerrilla conflict are yesterday’s news. Today tourists find themselves in what seems to be the best of all destinations... panoramic beaches, jungle hiking trails, breathtaking volcanoes and waterfalls, deserts, adventure sports, unmatched flora and fauna, centuries old indigenous cultures, and an almost daily celebration of food, fashion and festivals. The warm temperatures of the lowlands contrast with the cool of the highlands and the freezing nights of the upper Andes. Colombia is as rich in both nature and natural resources as any place in the world. It passionately protects its unmatched wildlife, while warmly sharing its coffee, its emeralds, and its happiness with the world. It boasts as many animal species as any country on Earth, hosting more than 1,889 species of birds, 763 species of amphibians, 479 species of mammals, 571 species of reptiles, 3,533 species of fish, and a mind-blowing 30,436 species of plants. Yet Colombia is so much more than jaguars, sombreros and the legend of El Dorado. A TIME magazine cover story properly noted “The Colombian Comeback” by explaining its rise “from nearly failed state to emerging global player in less than a decade.” It is respected as “The Fashion Capital of Latin America,” “The Salsa Capital of the World,” the host of the world’s largest theater festival and the home of the world’s second largest carnival. -

How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/9853 SHARE How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition DETAILS 384 pages | 7 x 10 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-07036-2 | DOI 10.17226/9853 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning with additional material from the Committee on Learning Research and Educational Practice, National Research Council FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition Expanded Edition How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning John D. Bransford, Ann L. Brown, and Rodney R. Cocking, editors with additional material from the Committee on Learning Research and Educational Practice M. Suzanne Donovan, John D. Bransford, and James W. Pellegrino, editors Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Feminist Periodicals

. The U n vers ty o f w sconsln System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 20, Number I, Spring 2000 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian F minist CD Peri 1 Is A current listing of contents Volume 20, Number 1 Spring 2000 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is pUblished by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on aquarterly basis with the intentof increasing pUblicawarenessoffeminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with awide spectrum offeminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to sUbscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from current issues of major feministjournals are reproduced in each issue of Feminisf Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. 5.