Fishery Management Plan for the Upper Sacramento River 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2230 Pine St. Redding

We know why high quality care means so very much. Since 1944, Mercy Medical Center Redding has been privileged to serve area physicians and their patients. We dedicate our work to continuing the healing ministry of Jesus in far Northern California by offering services that meet the needs of the community. We do this while adhering to the highest standards of patient safety, clinical quality and gracious service. Together with our more than 1700 employees and almost 500 volunteers, we offer advanced care and technology in a beautiful setting overlooking the City. Mercy Medical Center Redding is recognized for offering high quality patient care, locally. Designation as Blue Distinction Centers means these facilities’ overall experience and aggregate data met objective criteria established in collaboration with expert clinicians’ and leading professional organizations’ recommendations. Individual outcomes may vary. To find out which services are covered under your policy at any facilities, please contact your health plan. Mercy Heart Center | Mercy Regional Cancer Center | Center for Hip & Knee Replacement Mercy Wound Healing & Hyperbaric Medicine Center | Area’s designated Trauma Center | Family Health Center | Maternity Services/Center Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | Shasta Senior Nutrition Programs | Golden Umbrella | Home Health and Hospice | Patient Services Centers (Lab Draw Stations) 2175 Rosaline Ave. Redding, CA 96001 | 530.225.6000 | www.mercy.org Mercy is part of the Catholic Healthcare West North State ministry. Sister facilities in the North State are St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Red Bluff and Mercy Medical Center Mt. Shasta in Mt. Shasta Welcome to the www.packersbay.com Shasta Lake area Clear, crisp air, superb fi shing, friendly people, beautiful scenery – these are just a few of the words used to describe the Shasta Lake area. -

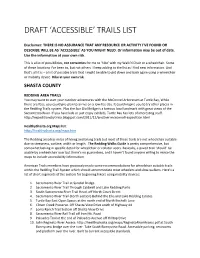

Draft 'Accessible' Trails List

DRAFT ‘ACCESSIBLE’ TRAILS LIST Disclaimer: THERE IS NO ASSURANCE THAT ANY RESOURCE OR ACTIVITY I'VE FOUND OR DESCRIBE WILL BE AS 'ACCESSIBLE' AS YOU MIGHT NEED. Or information may be out of date. Use the information at your own risk. This is a list of possibilities, not certainties for me to ‘hike’ with my Walk’n’Chair or a wheelchair. Some of these locations I’ve been to, but not others. I keep adding to the list as I find new information. And that’s all it is – a list of possible trails that I might be able to get down and back again using a wheelchair or mobility device. Hike at your own risk. SHASTA COUNTY REDDING AREA TRAILS You may want to start your outdoor adventures with the McConnel Arboretum at Turtle Bay, While there are fees, you could pre-plan to arrive on a low-fee day. It could inspire you to try other places in the Redding Trails system. Plus the Sun Dial Bridge is a famous local landmark with great views of the Sacramento River. If you have kids or just enjoy exhibits, Turtle Bay has lots of interesting stuff. http://expeditionsbytricia.blogspot.com/2011/12/another-mcconnell-expedition.html HealthyShasta.org Maps list: http://healthyshasta.org/maps.htm The Redding area has miles of hiking and biking trails but most of these trails are not wheelchair suitable due to steepness, surface, width or length. The Redding Walks Guide is pretty comprehensive, but somewhat lacking in specific detail for wheelchair or rollator users. Basically, a paved trail ‘should’ be usable by a wheelchair user but there’s no guarantees, and I haven’t found anyone willing to revise the maps to include accessibility information. -

Headwaters Sacramento River Ecosystem Analysis - I Table of Contents

Headwaters Sacramento United States River Ecosystem Analysis Department of Agriculture Mt. Shasta Ranger District Forest Service Shasta-Trinity National Forest Pacific Southwest Region January 2001, Version 2 (updated from version 1, dated August 29, 1995) For Further Information, Contact: Mount Shasta Ranger Station 204 West Alma Mt. Shasta, CA 96067 (530)926-4511 (530)926-4512 (TTY-TDD) (530)926-5120 (FAX) The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer Preface The Record of Decision for Amendment to Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Planning Documents within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl including Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late-Successional and Old Growth Related Species (herein called The President’s Plan), describes four components including riparian reserves, key watersheds, watershed analysis and watershed restoration. This report addresses those components with the exception of key watersheds, of which there are none in the Upper Sacramento River sub-basin. -

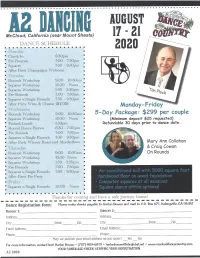

Lodging & RV Sites

McCloud Dance Country Lodging & RV Sites is located in the historic mill town, McCloud, McCloud Timber Inn Motel - King Beds, Kitchen Suites, California. Extend your stay before or after BBQ Area, Dancer Discount. Easy walking distance. 153 dancing with us and enjoy the many local Squaw Valley Road, McCloud, CA 96057; (530) 964-2893. attractions, a few of which are noted below. Cloud Nine - 3 BR, 2 bath, 225 California St. McCloud Nearby Recreation www.vrbo.com/893465 (707) 813-0964; Dancer Discount. In the Heart of McCloud-3 BR, 2 bath, 520 California St., Mount Shasta - Standing at 14,162 feet on www.vrbo.com/346855; (707) 813-0964; Dancer Discount. the summit of Mt. Shasta can be one of the The Guest House - A Secluded Country B&B Inn. 606 West most rewarding experiences of your life. With Colombero Drive (PO Box 1510), McCloud, CA 96057; Dancer 17 established routes, there is climbing Discount; (530) 964-3160; [email protected]; available for beginners as well as advanced www.guesthousemccloud.com mountaineers. www.climbingmtshasta.org/ The Old Mill House - 321 Broadway, McCloud, CA 96057, Golf - In McCloud, Fall River Mills, Lake (3 doors from Dance Country); 3 BR 1 Bath; Dancer rates; Shastina, Mount Shasta Resort, and Weed (530) 722-7310; www.vrbo.com/211623 McCloud River Mercantile Hotel - 241 Main Street (PO Fishing & Boating - McCloud River, Box 658), McCloud, CA 96057; Dancer Discount; (530) 964- Upper Sacramento River, Medicine Lake, 2602; [email protected], mccloudmercantile.com Castle Lake, McCloud Lake, Lake Siskiyou, and Lake Shasta McCloud Hotel & Sage Restaurant- Fully Air Conditioned, Lots of Extras; AAA 3 Diamond. -

2 Appendix C Cultural Tech Report

September 9, 2015 PACIFICORP Lassen Substation Project Cultural Resource Survey DRAFT REPORT Siskiyou County, California LEGAL DESCRIPTION: T40N, R4W, SECTIONS 9, 16, 17, AND 21 USGS QUADRANGLE: CITY OF MT. SHASTA, CA. PROJECT NUMBER: 136412 PROJECT CONTACT: Michael Dice EMAIL: [email protected] PHONE: 714-507-2700 POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey Cultural Resource Survey DRAFT REPORT PacifiCorp Lassen Substation Project Siskiyou County, California PREPARED FOR: PACIFICORP PREPARED BY: MICHAEL DICE 714-507-2700 [email protected] POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey CONFIDENTIAL This report contains information on the nature and location of prehistoric and historic cultural resources. Under California Office of Historic Preservation guidelines as well as several laws and regulations, the locations of cultural resource sites are considered confidential and cannot be released to the public. ANA 130-227 (PER 02) PACIFICORP (09/16/2015) 136412 YU PAGE i POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ANA 130-227 (PER 02) PACIFICORP (09/16/2015) 136412 YU PAGE ii POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS MANAGEMENT S UMMARY............................................................................................................ 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... -

Mount Shasta Collection Pamphlet File Topics

College of the Siskiyous Library Mount Shasta Collection PAMPHLET FILE TOPICS Updated April 2019 MS PAMPHLET TOPICS A Abrams Lake (Calif.) Achomawi Indians Adams, Mount (Wash.) Aetherius Society Ager Ah-Di-Na Campground Algomah Camp Art - Crafts, Jewelry, etc. Art – Engraving / Lithographs, etc. Art - Graphic Art, Logos, Drawing Art - Murals Art - Visionary Art & Artists Art & Artists - General Art & Artists - A Art & Artists - B Art & Artists - C Art & Artists - D Art & Artists - E Art & Artists - F Art & Artists - G Art & Artists - H Art & Artists - I Art & Artists - J Art & Artists - K Art & Artists - L Art & Artists - M Art & Artists - N Art & Artists - O Art & Artists - P Art & Artists - Q Art & Artists - R Art & Artists - S Art & Artists - T Art & Artists - U Art & Artists - V Art & Artists - W-X Art & Artists - Y-Z Art & Artists - Unidentified Ascended Master Teaching Foundation Ash Creek (Calif) Association of Sananda and Sanat Kumara (Sister Thedra) Ashtar Command Ashtara Foundation Athapascan Language Audio-Visual (Movies) Audubon Endeavor (Mt. Shasta Area Audubon) Authors - Local Avalanche Gulch Avalanches MS PAMPHLET TOPICS B Baird Station Hatchery – Livingston Stone Baker, Mount (Wash.) Baxter, J.H. Bear Springs (Mt. Shasta) Berry Family Estate Bicycling Big Canyon Big Ditch Big Springs (Mayten) Big Springs - Mount Shasta City Park Big Springs - Shasta Valley Biological Survey of Mount Shasta Biology Biology - Life Zones Bioregion - Mount Shasta Black Bart Black Butte Bohemiam Club (San Francisco) Bolam Glacier (Mount Shasta) -

Siskiyou County, California Mt

637± Acre Castle Lake Recreation Development Tract within Castle Crags 134 Wilderness, Near Mt. Shasta - Siskiyou County, California Mt. Shasta I-5 City of Mt. Shasta Lake Siskiyou Ney Springs Creek Little Castle Lake Castle Lake Castle Crags Wilderness Boundary N PUBLISHED RESERVE: $1,695,000 LAST ASKING: First Time Offered SIZE: 637± Acres ELEVATION: 5,400 to 6,200± Feet ZONING: RRB-40 (Rural Residential Agriculture -40) PROPERTY INSPECTION: At Any Time – Please Contact Auction Informa- tion Office [email protected] or 1-800-845-3524 for Road Condition to Ac- cess Property FINANCING: None – All Cash DESCRIPTION: This 637± acre block of land in the Mt. Shasta Trinity National Forest has a rare setting along the northeast shoreline of Castle Lake, the largest of 25 alpine lakes within the Upper Sacramento Watershed, and home to Castle Lake Environmental Research and Education Program at University of California, Davis, which is the longest running program of its kind in America. The Castle Lake Tract may have the most significant combination of conservation and recreation develop- ment opportunity for a large block of private land in Northwest California, with year-round access from I-5. The property includes frontage along Castle Lake, and has a spectacular landscape of granite outcrops, lush meadows with wildflowers, secluded Little Castle Lake, and an estimated 14 million board feet of primar- ily white and red fir, including old growth, some of which is over 200 years old. Please see Supplemental Information Package for Timber Inventory Report. Additionally, the entire property is zoned RRB-40 by Siskiyou County, which allows residential uses, and campground development. -

Sources of Existing Habitat-Related Data

Appendix D Sources of Existing Habitat-Related Data Table D-1. Content coverage and analysis for data and reports providing hydrologic information for the Sacramento and McCloud rivers. Document Period of Extent/ Author Year Title Data Content Collection Method Interval River Basin Sub-Basin Location(s) Comments Type Record Continuity PG&E 2013 PG&E MSS MeanDailyFlow pd of Data file River flow Stream gage Daily McCloud McCloud River at MSS 1993-2013 Complete Mean Daily MC-7 McCloud Dam Release with PG&E 2006 Data file River flow Stream gage Daily McCloud McCloud Dam MC-7 1973-2006 Complete Mean Daily est spill James B Black (MC11), McCloud PG&E 2009 Conduits - PHs Data file River flow Stream gage Daily Pit Tunnel (MC8), Pit No 5 PH, Pit No 1974-2006 Complete Mean Daily 6 PH, and Pit No 7 PH. PG&E 2009 Reservoirs Data file River flow Other Daily McCloud McCloud Reservoir (MC6) 1974-2006 Complete Mean Daily Pit 6 Reservoir (PH 58) and Pit 7 PG&E 2009 Reservoirs Data file River flow Other Daily Pit Reservoir (PH 59). Iron Canyon 1974-2006 Complete Mean Daily Reservoir (MC9) Duration Plots McCloud River PG&E 2009 Flow duration plots Data file Other Stream gage Other McCloud Complete streamflow gages PG&E MC7 Event Flow pd of PG&E 2013 Data file River flow Stream gage 15-min McCloud McCloud Dam MC-7 2011-2013 Complete record PG&E MCA Event Flow pd of PG&E 2013 Data file River flow Stream gage 15-min McCloud McCloud River MCA 2009-2013 Complete record PG&E; U.S. -

Modoc, Shasta, Siskiyou and Trinity CEDS 2013

COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY (CEDS) 2013 for the SUPERIOR CALIFORNIA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT Counties of MODOC, SHASTA, SISKIYOU, AND TRINITY Prepared by SUPERIOR CALIFORNIA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT 350 Hartnell Avenue, Suite A Redding, CA 96002 PHONE: (530) 225-2760 FAX: (530) 225-2769 [email protected] www.scedd.com EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Superior California Economic Development District (SCEDD) submits this Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) as a periodic comprehensive review and update as of January 24, 2012, as required by the United States Department of Commerce-Economic Development Administration (EDA). The CEDS provides historical data, outlines present economic situations, identifies opportunities for development and outlines broad plans for implementing defined strategies for improving and developing the local and District-wide economies. This document originated as an EDA sponsored “Overall Economic Development Program” report first completed in 1968 by Virgil Covington and Evangeline Manning, Shasta County Economic Development Corporation. This 2013 CEDS is a complete review and update of the CEDS previously reviewed and updated in 2002 and reviewed annually each year thereafter. The information contained in this CEDS is solicited from District board members, elected officials, administrators, public works officers, and the private sector business people throughout the four county area served by the District. Using the EDA CEDS guidelines, pertinent information and data was obtained and assembled by County and subject categories. This CEDS document was prepared by District staff on behalf of and under review of the Economic Development District CEDS Committee. This document, as submitted, is the final document as approved by the Superior California Economic Development District Board of Directors acting as the Economic Development District CEDS Committee. -

Pet Friendly Travel

PET FRIENDLY TRAVEL According to the Travel Industry Association of America, nearly 30 million people travel with pets each year. The Shasta Cascade offers travelers and their four legged friends an ideal destination for outdoor exploration, as well as pet friendly lodging and dining. Statistics show the majority of pet owners traveling with their critters by car are proud owners of pooches, so Redding provides all-access adventure for dogs and their human tagalongs. With over 200 miles of dog-friendly trails, sunny days year-round, lakes and rivers to paddle around in, your furry travel buddy would beg you to take a Redding trip if they could. Here’s a full list of pet-friendly places in Shasta Cascade by county: SHASTA COUNTY Pet-friendly Accommodations America’s Best Value Ponderosa Inn, 2220 Pine St., Redding, CA, (530)241-6300 Baymont Inn & Suites – Anderson, Arby Way & Factory Outlets Dr., Anderson, CA, (530)365-6100 Baymont Inn & Suites, 2600 Larkspur Lane, Redding, CA, (530)722-9100 Best Western Anderson Inn, 2688 Gateway Dr., Redding, CA, (530)365-2753 Best Western Plus Hilltop Inn, 2300 Hilltop Dr., Redding, CA (530)221-6100 Best Western Plus Twin View Inn, 1080 Twin View Blvd., Redding, CA, (530)241-5500 Burney Falls Lodging, 37371 Main St., Burney, CA, (530) 335-3300 Charm Motel, 37371 State Highway 299 E, Burney, CA, (530) 335-2254 Comfort Inn, 850 Mistletoe Lane, Redding, CA (530)221-4472 Deluxe Inn, 1135 Market St., Redding, CA, (530)243-5141 Fairfield Inn & Suites, 5164 Caterpillar Rd., Redding, CA, (530)243-3200 Fall River Lodge, 43288 Hwy 299E, Fall River Mills, CA, (530)336-5678 Gaia Shasta Hotel, 4125 Riverside Pl., Anderson, CA, (530)365-7077 HiMont Motel, Bridge St. -

Yreka Junction 127,148-Square-Foot Regional Shopping Center Located in Yreka, California Yreka Junction

OFFERING MEMORANDUM 127,148-SQUARE-FOOT REGIONAL SHOPPING CENTER LOCATED IN YREKA, CALIFORNIA YREKA JUNCTION 127,148-SQUARE-FOOT REGIONAL SHOPPING CENTER LOCATED IN YREKA, CALIFORNIA YREKA JUNCTION EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY Edward J. Nelson First Vice President Investments Director - National Retail Group Sacramento Phone: (916) 724-1326 [email protected] License: CA 01452610 OFFERING MEMORANDUM NON-ENDORSEMENT AND DISCLAIMER NOTICE CONFIDENTIALITY AND DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. -

The Code of the West... the Realities of Rural Living

The Code of the West... the Realities of Rural Living A Primer for Living in SISKIYOU COUNTY CALIFORNIA 2005 Edition Office of County Administrator P.O. Box 750 Yreka, California 96097 (530) 842-8005 www.co.siskiyou.ca.us TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENT ................................................... 1 EXPECTATIONS ........................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION TO PARADISE .......................................... 1 Locale ........................................................... 1 Terrain ........................................................... 1 The Four Corners of the County and Points Between . 2 Butte Valley/Tulelake/Medicine Lake Highlands . 2 Happy Camp/Klamath River . 2 Scott Valley and the Salmon River . 3 Dunsmuir ................................................... 3 Mt. Shasta .................................................. 3 McCloud ................................................... 4 Weed/Lake Shastina/Edgewood . 4 Yreka/Montague/Shasta Valley/Little Shasta . 4 Climate........................................................... 4 HIGH COUNTRY REALITIES ............................................. 5 The Right to be Rural . 5 Open Range Law . 5 Farm Life...Cows & Other Critters . 5 Right to Farm Ordinance . 5 Growth ........................................................... 6 Real Estate, Land & Just Plain Dirt . 6 Water, the Real Gold . 6 Sanitation ................................................... 6 Access ..................................................... 7 Property Boundaries