UNIVERSITY of FOGGIA Management Accounting Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food and Drink War and Peace

NATIONAL MUSEUM Of ThE AMERICAN INDIANSUMMER 2018 FooD AND DrINk Healthy Eating ANd SOvEREIgNTy ThE Persistence Of ChIChA + WAr AND PeAce hUMbLE Hero Of d-Day NAvAjO Treaty Of 1868 JOIN TODAY FOR ONLY $25 – DON’T MISS ANOTHER ISSUE! NATIONAL MUSEUM of the AMERICAN INDIANFALL 2010 DARK WATERS THE FORMIDABLE ART OF MICHAEL BELMORE EXPLAINING ANDEAN DESIGN THE REMARKABLE LARANCE SPECIAL ISSUE ............................... FAMILY DECEMBER INDIANS ON THE POST ART OFFICE MARKETS WALLS + A NEW VANTAGE POINT ON CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS JOIN TODAY AND LET THE MUSEUM COME TO YOU! BECOME A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL • 20% discount on all books purchased MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN from the NMAI web site FOR JUST $25 AND YOU’LL RECEIVE: • 10% discount on all purchases from • FREE 1 year subscription to our exclusive, the Mitsitam Café and all NMAI and full-color quarterly publication, American Smithsonian Museum Stores Indian magazine • Permanent Listing on NMAI’s electronic • Preferred Entry to the NMAI Mall Member and Donor Scroll Museum at peak visitor times Join online at www.AmericanIndian.si.edu or call toll free at 800-242-NMAI (6624) or simply mail your check for $25 to NMAI, Member Services PO Box 23473, Washington DC 20026-3473 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION 17 NMAI_FALL15.indd 16 2015-07-17 1:00 PM Contents SUMMER 2018 VOL. 19 NO. 2 18 10 ON THE COVER NATIONAL MUSEUM O F THE AMERICAN Traditional food and drink continue to sustain Indigenous identity and cultural (and political) survival. This richly carved Inka qero (wooden drinking cup) shows a mule team hauling house SUMMER 2018 beams to the highlands as a Native woman offers a INDIAN drink of chicha to the mule drivers. -

Prezentacja Programu Powerpoint

Discover new opportunities „Grana” Sp. z o.o. company and product offer presentation Company | About Grana company • One of the world’s largest producers of instant beverages made from cereals and chicory • We have been making cereal and chicory-based beverages for 100 years • We offer primarily top quality products developed thanks to our wealth of experience and state-of-the-art technologies. • We are a unit of the German Group Cafea - it is Grana in numbers one of the biggest companies in the world specialized in the production of instant coffees for the private label market. - 26 000 sq. m plot area - 25 000 sq. m production area • We cooperate with clients from all over the - 6 100 sq. m. warehouse area world and our products are available in stores across Europe as well as the US, Canada, Japan - 290 employees and Malaysia. Production process | Production process Producing an instant beverage is a technologically demanding task but it can be simply described as follows. The best quality ingredients undergo the following processes: roasting and water extraction (which enables obtaining the liquid essence of the ingredients). Next, the extract is dried. After drying we obtain a quick and easy-to-prepare powder/granules with a delicate taste and aroma and amber-coffee colour. Selection & delivery Roasting Extraction Drying Packaging Raw materials, mainly One of the most Roasted semi- Liquid essence is Finished products cereals and chicory – important production products undergo dried by hot air in can be packed in used for production processes during water extraction one of the two jars, cans, bags, come from selected which raw materials process during which drying towers. -

Final Report Specialty Coffee and Cocoa

Value Chain Analysis CBI Integrated Country Programme Final Report Specialty coffee and cocoa Contact: Udo Censkowsky +49-89-82075902 [email protected] www.organic-services.com 1 Organic Services - committed to creating value www.organic-services.com Content 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 3 2. Market demand in the European Union ............................................................ 4 2.1. Global situation and European imports ....................................................... 4 2.2. Domestic market trends in Peru ................................................................ 10 2.3. EU import requirements ............................................................................ 11 3. Coffee & cacao value chain analysis .............................................................. 14 3.1. Governance of the coffee and cocoa sector ............................................. 14 3.2. Status-Quo production and trends ............................................................ 15 3.3. Value Chain Analysis ................................................................................ 19 4. Number of Peruvian companies ...................................................................... 25 5. Risk assessment and opportunities ................................................................ 26 6. Role of stakeholders in a CBI country programme.......................................... 33 7. Corporate Social Responsibility -

Greener Products; Earth Week Information

A PUBLICATION OF WILLY STREET CO-OP, MADISON, WI VOLUME 45 • ISSUE 4 •APRIL 2018 IN THIS ISSUE: Run for the Board; Greener Products; Earth Week Information; West Expansion Update; and More! PAID PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. MADISON, WI MADISON, PERMIT NO. 1723 NO. PERMIT 1457 E. Washington Ave • Madison, WI 53703 Ave 1457 E. Washington POSTMASTER: DATED MATERIAL POSTMASTER: DATED CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED CHANGE SERVICE WILLY STREET CO-OP MISSION STATEMENT The Williamson Street Grocery Co-op is an economically and environmentally sustainable, coop- READER eratively owned grocery business that serves the needs of its Owners Published monthly by Willy Street Co-op and employees. We are a cor- East: 1221 Williamson Street, Madison, WI 53703, 608-251-6776 nerstone of a vibrant community West: 6825 University Ave, Middleton, WI 53562, 608-284-7800 in south-central Wisconsin that North: 2817 N. Sherman Ave, Madison, WI 53704, 608-471-4422 provides fairly priced goods and Central Office: 1457 E. Washington Ave, Madison, WI 53703, 608-251-0884 services while supporting local EDITOR & LAYOUT: Liz Wermcrantz and organic suppliers. ADVERTISING: Liz Wermcrantz COVER DESIGN: Hallie Zillman-Bouche SALE FLYER DESIGN: Hallie Zillman-Bouche GRAPHICS: Hallie Zillman-Bouche SALE FLYER LAYOUT: Liz Wermcrantz WILLY STREET CO-OP PRINTING: Wingra Printing Group BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Willy Street Co-op Reader is the monthly communications link among the Co-op Board, staff and Owners. It provides information about the Co-op’s services Holly Fearing, President and business as well as about cooking, nutrition, health, sustainable agriculture and Patricia Butler more. -

FIC-Prop-65-Notice-Reporter.Pdf

FIC Proposition 65 Food Notice Reporter (Current as of 9/25/2021) A B C D E F G H Date Attorney Alleged Notice General Manufacturer Product of Amended/ Additional Chemical(s) 60 day Notice Link was Case /Company Concern Withdrawn Notice Detected 1 Filed Number Sprouts VeggIe RotInI; Sprouts FruIt & GraIn https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers Cereal Bars; Sprouts 9/24/21 2021-02369 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. SpInach FettucIne; 02369.pdf Sprouts StraIght Cut 2 Sweet Potato FrIes Sprouts Pasta & VeggIe https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers 9/24/21 2021-02370 Sauce; Sprouts VeggIe Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. 3 Power Bowl 02370.pdf Dawn Anderson, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02371 Sprouts Farmers OhI Wholesome Bars Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 4 Market, Inc. 02371.pdf Brad's Raw ChIps, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02372 Sprouts Farmers Brad's Raw ChIps Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 5 Market, Inc. 02372.pdf Plant Snacks, LLC; Plant Snacks Vegan https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02373 Sprouts Farmers Cheddar Cassava Root Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 6 Market, Inc. ChIps 02373.pdf Nature's Earthly https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl ChoIce; Global JuIces Nature's Earthly ChoIce 9/24/21 2021-02374 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- and FruIts, LLC; Great Day Beet Powder 02374.pdf 7 Walmart, Inc. Freeland Foods, LLC; Go Raw OrganIc https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02375 Ralphs Grocery Sprouted Sea Salt Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 8 Company Sunflower Seeds 02375.pdf The CarrIngton Tea https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl CarrIngton Farms Beet 9/24/21 2021-02376 Company, LLC; Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Root Powder 9 Walmart, Inc. -

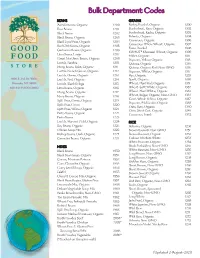

Bulk Numerical Codes

BBulkulk DepartmentDepartment CCodesodes BBEANSEANS GGRAINSRAINS Adzuki Beans, Organic 1200 Barley, Pearled, Organic 1300 Fava Beans 1201 Buckwheat, Raw, Organic 1302 Black Beans 1202 Buckwheat, Kasha, Organic 1303 Black Beans, Organic 1203 Polenta, Organic 1304 Black Eyed Peas, Organic 1204 Couscous, Organic 1306 Red Chili Beans, Organic 1205 Couscous, Whole Wheat, Organic 1307 Farro, Pearled 1308 Garbanzo Beans, Organic 1206 KAMUT ® Khorasan Wheat, Organic 1309 Lima Beans, Large 1207 Millet, Organic 1311 Great Northern Beans, Organic 1208 Popcorn, Yellow, Organic 1313 Lentils, Pardina 1210 Quinoa, Organic 1314 Mung Beans, Split, Organic 1211 Quinoa, Organic Red, Non-GMO 1315 Lentils, French Green, Organic 1212 Popcorn, White, Organic 1317 Lentils, Green, Organic 1213 Rye, Organic 1329 Lentils, Red, Organic 1214 Spelt, Organic 1330 Lentils, Black Beluga 1215 Wheat, Hard Red, Organic 1331 Lima Beans, Organic 1216 Wheat, Soft White, Organic 1332 Mung Beans, Organic 1217 Wheat, Hard White, Organic 1333 Navy Beans, Organic 1218 Wheat, Bulgar, Organic, Non-GMO 1334 Split Peas, Green, Organic 1219 Corn, Whole Yellow, Organic 1337 Popcorn, Multicolor, Organic 1338 Split Peas, Green 1220 Oats, Raw, Organic 1340 Split Peas, Yellow, Organic 1221 Oats, Steel Cut, Organic 1341 Pinto Beans, Organic 1222 Couscous, Israeli 1342 Pinto Beans 1223 Lentils, Harvest Gold, Organic 1224 RRICEICE Soy Beans, Organic 1225 Arborio, Organic 1250 13 Bean Soup Mix 1226 Brown Basmati, Non-GMO 1251 Kidney Beans, Dark, Organic 1227 Brown Basmati, Organic 1252 Cannelini -

Cafea, Pâine Și Mic Dejun

CAFEA, PÂINE ȘI MIC DEJUN Pan Blanco Paine Bun de ToT Dulceata Maple Joe Sirop de Albina carpatina alba fara gluten 250 afine fara zahar 360 artar bio 250g Miere tei 360 g g g Pret: 37.99 RON Pret: 14.79 RON Pret: 7.99 RON Pret: 19.99 RON Apimelia Miere Nutella crema de Vreau din Romania Vreau din Romania poliflora 400 g alune 400 g Toast clasic 600 g Toast integral 600 g Pret: 12.79 RON Pret: 11.49 RON Pret: 2.99 RON Pret: 2.99 RON Jacobs Kronung Doncafe Selected Jacobs Kronung Doncafe Selected Cafea macinata 500 Cafea macinata 600 Cafea macinata 250 Cafea macinata 300g g g g Pret: 9.99 RON Pret: 19.99 RON Pret: 17.49 RON Pret: 11.99 RON Jacobs Cafea 3 in 1 NESCAFE GOLD NESCAFE GOLD NESCAFE GOLD instant 15,2 g DOUBLE CHOCA CAPPUCINO 8 X 14 G VANILLA LATTE 8 X Pret: 0.59 RON MOCHA 8X18,5 G Pret: 0.89 RON 18,5 G Pret: 0.89 RON Pret: 0.89 RON NESCAFE 3 IN 1 NESCAFE 3 IN 1 NESCAFE 3 IN 1 MILD NESCAFE 3 IN 1 ZAHAR BRUN 16,5 G FRAPPE 16 G PLIC 15 G ORIGINAL 16,5 G Pret: 0.59 RON Pret: 0.59 RON Pret: 0.59 RON Pret: 0.59 RON Tchibo Exclusive Tassimo Jacobs Caffe Amigo Cafea instant Tchibo Espresso Cafea macinata 500 Crema XL 132,8 g 300 g Cafea boabe 1 kg g Pret: 21.09 RON Pret: 29.99 RON Pret: 55.69 RON Pret: 19.99 RON Davidoff Rich Aroma Nescafe Brasero Tchibo Exclusive Nescafe Espresso Cafea macinata 250 Cafea instant Cafea macinata 250 intenso capsule 16X8 g Original 200 g g g Pret: 25.19 RON Pret: 20.99 RON Pret: 9.99 RON Pret: 23.99 RON Jacobs Kronung Nesquik Cacao Cafissimo Cafea Rich Lavazza Crema Cafea decofeinizata instant 400 g Aroma 80 g Gusto Cafea 250 g Pret: 10.19 RON Pret: 11.99 RON macinata 250 g Pret: 15.39 RON Pret: 18.29 RON Nescafe Lungo Inka inlocuitor cafea La Festa Bautura Lavazza Q. -

PLD-PLD DIET MENUS Plant Based Alkaline Diet Low Salt Or 1200 Mg Sodium - Neutral Protein 0.6 Grams Protein/KG Body Weight Water Or Twice Your Urinary Output

PLD-PLD DIET MENUS Plant Based Alkaline Diet Low salt or 1200 mg sodium - Neutral Protein 0.6 Grams Protein/KG Body Weight Water or twice your Urinary Output Upon Arising One teaspoon of solé in a glass of water To help balance your stomach, after eating raw fruit or drinking citrus, wait twenty minutes before eating again. Freshly squeezed juice from one lemon. Add enough water to make ¼ cup or– Orange juice freshly squeezed (wait 20 minutes after citrus before eating) or– Grapefruit juice freshly squeezed (Caution can interfere with certain medications). Throughout the day, if permitted, drink water equal to twice your output to turn off vasopressin, a hormone that stimulates cyst growth. Breakfast Menu To help balance your stomach, after eating raw fruit or drinking citrus, wait 20 minutes before eating again. Fruit: Raw fresh fruit in season locally grown (AVOID starfruit, rhubarb, strawberry, whole blueberry, whole cranberries, plum, prunes, noni, tamarind) Fruit: Freshly sliced grapefruit (caution interferes with certain medications) Fruit: Bananas, apples or stewed fruit. Cereal: Spelt, rye, kamut, barley, grits, corn meal, steel cut oats, oatmeal cereal (soak grains overnight). Cereal: Corn meal with chopped dates (soak corn meal overnight). Cereal: Cold cereal with almond, coconut milk. Spelt, rye, kamut, barley or corn cereal. Cereal: Prepare ½ cup of spelt kernels that have been soaked overnight to diminish phytic acid. Whole spelt kernels chopped have been likened to ground nuts. The following morning heat and top with banana or cinnamon apples. Toasted non-yeasted English Muffin with all fruit spread. Bread made with spelt, rye, kamut, or corn. -

Enter Your Title Here in All Capital Letters

DEVELOPMENT AND EVALUATION OF A SORGHUM TISANE by ANGELA LYNN DODD B.S., Kansas State University, 2008 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Food Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Fadi Aramouni Dept. of Animal Science & Industry Abstract Known for its antioxidant activity and other health benefits, tea is the second most consumed beverage in the world, following water. With up to 6% (w/w) of phenolic compounds, sorghum has the highest content compared to other cereals. The objective of this research was to develop and analyze a sorghum tisane using two different red sorghum hybrids. Tisanes are herbal infusions composed of anything other than the leaves from the Camellia sinensis plant. The sorghum kernel was cracked using an Allis experimental roll stand equipped with a Le Page cut mill. Samples were sifted at 180 RMP- 4” diameter throw for 2 min. The two hybrids were roasted in a Whirlpool convection oven at 212°C for 13 or 15 min. Three fruit and herbal combinations were tested to increase consumer acceptability. Samples was brewed for 4 min in 8fl.oz at 100°C. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity(ORAC) and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) were used to analyze the beverage along with chemical, physical and sensory tests. TPC results showed sorghum tisane to have 38.5±6.91 mg gallic acid equivalence/ 8fl oz. and 433.7 ±7.11 μM Trolox equivalence/ 236.6 mL (8 fl.oz, 1 cup) for an ORAC value. Fruit and herbal combinations were also added to the sorghum to increase overall consumer acceptability. -

Clean up Your

Clean Up Your Act Phase 1: Preparation During the week prior to starting your detox support ReSet program, you’ll want to start getting yourself ready by reducing your intake of certain substances that can be problematic if you go “cold turkey”. Titrate yourself down in doses (meaning reduce a little at a time) until you are at zero intake for the start of Phase 2. What we are intending here is to give your elimination systems a break and let them catch up. We aren’t going to overload them during a period when they are already exhausted. When we do that we risk pushing the body into both metabolic and immunologic danger zones. We will talk about each of these during class. Not all of these are problematic for regular consumption, but it’s good to take a short break from regular habits. Slowly reduce your consumption of these items so that you start Phase 2 without them. Substances Sources Substitutes caffeine (tip: either teas (green, black, Teeccino, chicory root gradually substitute decaf matcha, chai, etc), coffee, (Inka, Cafix, Pero, Kaffree or gradually swap in one of sodas, energy drinks, Roma) kombucha, maca, the listed substitutes; don’t appetite suppressants, yerba mate, any herbal tea go “cold turkey” or you some medications (like may end up with a nasty Motrin) headache; stay hydrated) alcohol (tip: drink one of beer, wine, liquor, herbal mineral water, naturally the substitutes from a tinctures, cough syrups, bubbly water, herbal tea beautiful wine glass) etc sugar (tip: if you crave table sugar, fructose whole stevia leaf (not sweet, reach for fruit. -

Alchemy of Being

ALCHEMY OF BEING MODULE 1 STUDY NOTES ENERGETICS Copyright © 2021 Nicky Clinch Ltd. All Rights Reserved Copyright © 2021 Nicky Clinch Ltd. All Rights Reserved 1 THE HISTORY & PHILOSOPHY OF MACROBIOTICS Why Look at the History of Macrobiotics? The origins of any teaching reveals a lot about the character and content of that teaching. We can learn much about the character of macrobiotics by seeing where it has come from. This allows us to put macrobiotics in context of other teachings and practices around the world, and especially at this time with modern western understandings. LAO TZU (around 604-531 BC) Lao Tzu is said to have written the Tao Te Ching, describing the creation of the universe and its workings of the relative world. Here is a translation of the first two chapters, from the book ‘The Complete Works of Lao Tzu’ by Ni Hua-Ching that is beautiful and worth a read. To give you a context to the depth of the work of field and flow In which we work in in the realm of maturation. Copyright © 2021 Nicky Clinch Ltd. All Rights Reserved 2 Macrobiotics in the West ANCIENT GREECE The word ‘macrobios’ was used to describe a natural way of living and eating to create Big Long Life – Health and Longevity “Let food be thy medicine, and medicine be thy food”. Hippocrates ( 5th C BC) And there are many types of ‘food’. The environment we are in, the energy field we are living in and living from. All that we take in and absorb is some form of food. -

Highland Wholefoods Workers Co-Operative Ltd

Pricelist facebook.com/highlandwholefoods @highlandwholefd Highland Wholefoods Workers Co-operative Ltd. Unit 6, 13 Harbour Road, Inverness IV1 1SY Tel: 01463 712393 Fax: 01463 715586 Email: [email protected] Website: www.highlandwholefoods.co.uk WELCOME to Highland Wholefoods Spring pricelist. We hope you enjoy trading with us, whether you visit our showroom in Inverness or place orders via phone, email or fax. Orders can be delivered to your door or collected from our Inverness warehouse. Delivery is currently free to mainland and Skye destinations for ex-VAT invoice values over £200; if your order value is under £200 there is a £7.50 charge to- wards the cost of carriage. Delivery to most areas is within 1–2 days. Please call the sales office for delivery information for areas out with the mainland and Skye. Thank you for trading with Highland Wholefoods—your local workers co-operative, serving the area since 1989! The Highland Wholefoods Team Contents Highland Wholefoods Terms of Trade 3 Pricing Notes 3 Muesli and Mix Products Contents 4 Note re Allergens and Commodities 4 MAIN PRICELIST 5 BABYFOOD ............................................................ 5 BABYCARE PRODUCTS ........................................ 5 NANS PITTAS POPADOMS ................................. 53 BEANS & PULSES DRIED ..................................... 5 NATURAL REMIDIES .......................................... 53 SUPERFOODS ........................................................ 7 NUTS ...................................................................