Chapter Eleven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: the Very English Ambience of It All

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Hillstrom Museum of Art SEE PAGE 14 Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Opening Reception Monday, September 12, 2016, 7–9 p.m. Nobel Conference Reception Tuesday, September 27, 2016, 6–8 p.m. This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Katie Penkhus, who was an art history major at Gustavus Adolphus College, was an accomplished rider and a lover of horses who served as co-president of the Minnesota Youth Quarter Horse Association, and was a dedicated Anglophile. Hillstrom Museum of Art HILLSTROM MUSEUM OF ART 3 DIRECTOR’S NOTES he Hillstrom Museum of Art welcomes this opportunity to present fine artworks from the remarkable and impressive collection of Dr. Stephen and Mrs. Martha (Steve and Marty) T Penkhus. Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All includes sixty-one works that provide detailed glimpses into the English countryside, its occupants, and their activities, from around 1800 to the present. Thirty-six different artists, mostly British, are represented, among them key sporting and animal artists such as John Frederick Herring, Sr. (1795–1865) and Harry Hall (1814–1882), and Royal Academicians James Ward (1769–1859) and Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959), the latter who served as President of the Royal Academy. Works in the exhibit feature images of racing, pets, hunting, and prized livestock including cattle and, especially, horses. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape

CONSTABLE, GAINSBOROUGH, TURNER AND THE MAKING OF LANDSCAPE THE JOHN MADEJSKI FINE ROOMS 8 December 2012 – 17 February 2013 This December an exhibition of works by the three towering figures of English landscape painting, John Constable RA, Thomas Gainsborough RA and JMW Turner RA and their contemporaries, will open in the John Madejski Fine Rooms and the Weston Rooms. Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape will explore the development of the British School of Landscape Painting through the display of 120 works of art, comprising paintings, prints, books and archival material. Since the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, its Members included artists who were committed to landscape painting. The exhibition draws on the Royal Academy’s Collection to underpin the shift in landscape painting during the 18 th and 19 th centuries. From Founder Member Thomas Gainsborough and his contemporaries Richard Wilson and Paul Sandby, to JMW Turner and John Constable, these landscape painters addressed the changing meaning of ‘truth to nature’ and the discourses surrounding the Beautiful, the Sublime and the Picturesque. The changing style is represented by the generalised view of Gainsborough’s works and the emotionally charged and sublime landscapes by JMW Turner to Constable’s romantic scenes infused with sentiment. Highlights include Gainsborough’s Romantic Landscape (c.1783), and a recently acquired drawing that was last seen in public in 1950. Constable’s two great landscapes of the 1820s, The Leaping Horse (1825) and Boat Passing a Lock (1826) will be hung alongside Turner’s brooding diploma work, Dolbadern Castle (1800). -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and Name/Date/Relationship to Wilson)

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and name/date/relationship to Wilson) Alken: Samuel Alken, 1756-1815, Engraver Anderdon: James Hughes Anderdon, 1790-1879, Patron Archer: Robert Archer, 1811, Publisher Ayscough: Dr Francis Ayscough, 1701-1763, Sitter Bacon: Sir Hickman Bacon, Baronet, 1855-1945, Collector Barnard: John Barnard, 1709-1784, Collector. Bathe: General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe, 1823-1907, Collector Beaumont: Sir George Beaumont, 1753-1827, Collector Beckingham: Stephen Beckingham, c.1730-1813, Collector Birch: William Birch, 1755-1834, Printmaker Blundell: Henry Blundell, 1724-1810, Patron Booth R.S.: The Revd. Richard Sawley Booth, 1762-1807, Collector Booth, E.: Elizabeth Booth, 1763-1819, Collector Booth, M: Marianne Booth, Lady Ford, 1767-1849, Collector Booth: Benjamin Booth, 1732-1807, Collector Boydell: John Boydell, 1720-1804, Publisher Brettingham: M. Matthew Brettingham, 1725-1803, Patron Bridgewater: Lord Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater, 1736-1803, Patron Brocklebank: Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hugh Royds Brocklebank, 1881-1911, Collector Browne: John Browne, 1742-1801, Engraver Byrne: William Byrne, 1743-1805, Engraver Canot: Pierre-Charles Canot, c.1710-1777, Engraver Carpenter: William Hookham Carpenter, 1792-1866, Collector Cavan: Frederick Rudolph Lambart, 1865-1947, Collector Chambers: Sir William Chambers, 1722-1796, Friend Champernowne: Arthur Melville Champernowne, 1871-1946, Collector Clarke: Frederick Seymour Clarke, 1855-1933, Collector Colebrook: Sir George Colebrook, 1729-1809, Collector Constable: John Constable, 1776-1837, Successor Cook: Sir Francis Cook, 1817-1901, Collector Cooper: Douglas Cooper, 1911-1984, Writer Cotman: John Sell Cotman, 1782-1842, Artist Courtenay: William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount, 1742-1788, Patron Coventry: George William, 6th Earl of Coventry, 1722-1809, Patron Dartmouth: William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, 1731-1801, Patron Daulby: Daniel Daulby, d. -

George Stubbs (London 1724 - 1806)

George Stubbs (London 1724 - 1806) A lion and a lioness Circa: 1778 1778 45.4 x 61 cm Signed and dated Geo: Stubbs Pinx. / 1778 lower centre George Stubbs was not only an immensely talented painter of sporting subjects but also a man imbued with the vigorous spirit of scientific enquiry that characterised the age of the Enlightenment. Like so many of his contemporaries he visited Italy (1754-5) where his study of Antique sculpture was to provide him with lasting inspiration. However, on his return to England he devoted himself to two years of the most painstaking and detailed dissection of horses that led to his acclaimed Anatomy of the Horse series of engravings, eventually published by J. Purser in 1766. This marriage of art and science was very much a feature of the lives of educated men in the second half of the eighteenth century, common not only to fellow artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby but also to members of the influential Whig aristocracy (among which Lord Rockingham and the Duke of Richmond were patrons of Stubbs) and men of industry such as the ceramics manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood. This recently discovered work, signed and dated 1778, must be among the first fruits of Stubbs’ collaboration with Wedgwood. Stubbs had been experimenting with enamel on copper since 1769 and first exhibited an example in 1770 with the Society of Artists, Lion Devouring a Horse (enamel on copper, Tate Gallery, London). However, he soon tired of using copper as a support due to the restriction its use imposed on the size of works it was possible to produce. -

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A. -

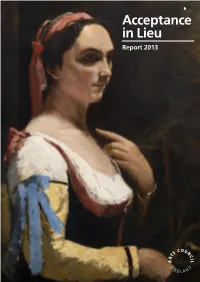

Acceptance in Lieu Report 2013 Contents Preface Appendix 1 Sir Peter Bazalgette, Chair, Arts Council England 4 Cases Completed 2012/13 68

Back to contents Acceptance in Lieu Report 2013 Contents Preface Appendix 1 Sir Peter Bazalgette, Chair, Arts Council England 4 Cases completed 2012/13 68 Introduction Appendix 2 Edward Harley, Chairman of the Acceptance in 5 Members of the Acceptance in Lieu 69 Lieu Panel Panel during 2012/13 Government support for acquisitions 6 Appendix 3 Allocations 6 Expert advisers 2012/13 70 Archives 7 Additional funding 7 Appendix 4 Conditional Exemption 7 Permanent allocation of items reported in earlier 72 years but only decided in 2012/13 Acceptance in Lieu Panel membership 8 Cases 2012/13 1 Hepworth: two sculptures 11 2 Chattels from Knole 13 3 Raphael drawing 17 4 Objects relating to Captain Robert Falcon Scott RN 18 5 Chattels from Mount Stewart 19 6 The Hamilton-Rothschild tazza 23 7 The Westmorland of Apethorpe archive 25 8 George Stubbs: Equestrian Portrait of John Musters 26 9 Sir Peter Lely: Portrait of John and Sarah Earle 28 10 Sir Henry Raeburn: two portraits 30 11 Archive of the 4th Earl of Clarendon 32 12 Archive of the Acton family of Aldenham 33 13 Papers of Charles Darwin 34 14 Papers of Margaret Gatty and Juliana Ewing 35 15 Furniture from Chicheley Hall 36 16 Mark Rothko: watercolour 38 17 Alfred de Dreux: Portrait of Baron Lionel de Rothschild 41 18 Arts & Crafts collection 42 19 Nicolas Poussin: Extreme Unction 45 20 The Sir Denis Mahon collection of Guercino drawings 47 21 Two Qing dynasty Chinese ceramics 48 22 Two paintings by Johann Zoffany 51 23 Raphael Montañez Ortiz: two works from the 53 Destruction in Art Symposium 24 20th century studio pottery 54 25 Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: L'Italienne 55 Front cover: L‘Italienne by Jean-Baptiste 26 Edgar Degas: three sculptures 56 Camille Corot. -

The Art of Unknown Animals Visitor Activities Evaluation Report

Strange Creatures: The art of unknown animals visitor activities evaluation report Contents 1. Overview and context ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Strange Creatures: The art of unknown animals exhibition ............................................................... 4 2.1 Aims............................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 What happened ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Facts and figures ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Exhibition audience evaluation themes ........................................................................................ 7 2.5 Exhibition participant evaluation themes ................................................................................... 10 3. Strange Creatures: The art of unknown animals events programme ............................................... 11 3.1 Aims and objectives .................................................................................................................... 11 3.2 What happened .......................................................................................................................... 12 3.3 Facts and figures ........................................................................................................................ -

2003/1 (6) 1 Art on the Line

Art on the line EXHIBITION REVIEW: Thomas Jones 1742-1803 Jonathan Blackwood School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Glamorgan, Pontypridd, CF37 1DL, Wales [email protected] This magnificent monographic show, curated roots in rural mid Wales as well as his train- by Ann Sumner, will do much to introduce ing under Wilson and the dramatic impact gallery visitors to the work of Thomas Jones that Italy, and Naples in particular, was to and restore him to his rightful place as an have on his work. The culmination of his important figure in UK landscape painting, in years in London and his membership of the the second half of the eighteenth century. Society of Artists was The Bard of 1774. Jones was born in Radnorshire in 1742 Based on Thomas Gray’s poem, published in and initially seemed destined for a career as 1757, the painting fuses Wilsonian land- a clergyman. However, a change of heart scape ideas with a dramatic staging of saw him train as an artist under Richard Edward I’s massacre of the Welsh bards Wilson (1761-63), and then exhibit as a under an apocalyptic sky. The painting is a member of the Society of Artists from 1766 striking and arresting summary of the rapid onwards. A decade later, Jones left the and capable development of Jones’ talent in United Kingdom for some years in Italy, the first years of his career. spent mainly in Rome and Naples. He came Just over half the exhibits are devoted to back in 1783 on the death of his father and Jones’ years in Italy from 1776-83. -

The Guennol Lioness

London | Mitzi Mina | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 6000 Marie-Béatrice Morin | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 5522 New York | Ali Malizia | [email protected] | +1 212 606 7176 Sotheby’s to sell ONE OF GEORGE STUBBS’ MOST CELEBRATED WORKS Testament to the Artist’s Masterful Depiction of Animal Anatomy, This Composition with two Leopard Cubs ranks among his Most Popular Subjects One of the rare examples of Stubbs’ big cat paintings to appear on the market in recent years, The work will be exhibited around the globe before its sale in London in July George Stubbs (1724-1806), Tygers at Play, oil on canvas, 101.5 by 127cm; 40 by 50 in. (est. £4-6 million) London, 27 March 2014 – Tygers at Play, one of George Stubbs’ most celebrated works is to lead Sotheby’s London Evening Sale of Old Master and British Paintings on 9 July 2014. Painted circa 1770-75, this masterful depiction of two leopard cubs ranks among Stubbs’ most popular subjects, reproduced in numerous prints. The painting itself, however, has rarely been seen in public, having been exhibited only four times since its original appearance at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Testament to the artist’s exceptional eye for capturing the animal form, this admirably preserved work boasts impeccable provenance, having been sold only once since it was commissioned from the English painter. It remained in the possession of a single family until 1962, when it was acquired by the present owners. Coming from a distinguished British aristocratic collection, Tygers at Play will be offered with an estimate of £4-6 million.