Who Shot J.R.? the Assassination of Philip II of Macedonia. a Source Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Ancient History

2003 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION Ancient History Total marks – 100 Section I Pages 2–5 Personalities in Their Times – 25 marks • Attempt ONE question from Questions 1–12 •Allow about 45 minutes for this section Section II Pages 9–22 Ancient Societies – 25 marks • Attempt ONE question from Questions 13–25 General Instructions •Allow about 45 minutes for this section • Reading time – 5 minutes Section III Pages 25–31 •Working time – 3 hours •Write using black or blue pen Historical Periods – 25 marks • Attempt ONE question from Questions 26–44 •Allow about 45 minutes for this section Section IV Pages 33–45 Additional Historical Period OR Additional Ancient Society – 25 marks • Attempt ONE question from Questions 45–63 OR ONE question from Question 64–76 • Choose a different Ancient Society from the one you chose in Section II, or a different Historical Period from the one you chose in Section III •Allow about 45 minutes for this section 104 Section I — Personalities in Their Times 25 marks Attempt ONE question from Questions 1–12 Allow about 45 minutes for this section Answer the question in a writing booklet. Extra writing booklets are available. Page Question 1 — Option A – Egypt: Hatshepsut ................................................................. 3 Question 2 — Option B – Egypt: Akhenaten .................................................................. 3 Question 3 — Option C – Egypt: Ramesses II ................................................................ 3 Question 4 — Option D – Near East: Sennacherib .............................................................. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Kings & Events of the Babylonian, Persian and Greek Dynasties

KINGS AND EVENTS OF THE BABYLONIAN, PERSIAN, AND GREEK DYNASTIES 612 B.C. Nineveh falls to neo-Babylonian army (Nebuchadnezzar) 608 Pharaoh Necho II marched to Carchemesh to halt expansion of neo-Babylonian power Josiah, King of Judah, tries to stop him Death of Josiah and assumption of throne by his son, Jehoahaz Jehoiakim, another son of Josiah, replaced Jehoahaz on the authority of Pharaoh Necho II within 3 months Palestine and Syria under Egyptian rule Josiah’s reforms dissipate 605 Nabopolassar sends troops to fight remaining Assyrian army and the Egyptians at Carchemesh Nebuchadnezzar chased them all the way to the plains of Palestine Nebuchadnezzar got word of the death of his father (Nabopolassar) so he returned to Babylon to receive the crown On the way back he takes Daniel and other members of the royal family into exile 605 - 538 Babylon in control of Palestine, 597; 10,000 exiled to Babylon 586 Jerusalem and the temple destroyed and large deportation 582 Because Jewish guerilla fighters killed Gedaliah another last large deportation occurred SUCCESSORS OF NEBUCHADNEZZAR 562 - 560 Evil-Merodach released Jehoiakim (true Messianic line) from custody 560 - 556 Neriglissar 556 Labaski-Marduk reigned 556 - 539 Nabonidus: Spent most of the time building a temple to the mood god, Sin. This earned enmity of the priests of Marduk. Spent the rest of his time trying to put down revolts and stabilize the kingdom. He moved to Tema and left the affairs of state to his son, Belshazzar Belshazzar: Spent most of his time trying to restore order. Babylonia’s great threat was Media. -

All About Indian History

Toprankers - Paramount SSC CGL Mock Test Get Test Series Put code - "EXAMPUNDIT" to avail discount Now Indian History - In Details INDIAN HISTORY PRE-HISTORIC as a part of a larger area called Pleistocene to the end of the PERIOD Jambu-dvipa (The continent of third Riss, glaciation. Jambu tree) The Palaeolithic culture had a The pre-historic period in the The stages in mans progress from duration of about 3,00,000 yrs. history of mankind can roughly Nomadic to settled life are The art of hunting and stalking be dated from 2,00,000 BC to 1. Primitive Food collecting wild animals individually and about 3500 – 2500 BC, when the stage or early and middle stone later in groups led to these first civilization began to take ages or Palaeolithic people making stone weapons shape. 2 . Advanced Food collecting and tools. The first modern human beings stage or late stone age or The principal tools are hand or Homo Sapiens set foot on the Mesolithic axes, cleavers and chopping Indian Subcontinent some- tools. The majority of tools where between 2,00,000 BC and 3. Transition to incipient food- found were made of quartzite. 40,000 BC and they soon spread production or early Neolithic They are found in all parts of through a large part of the sub- 4. settled village communities or India except the Central and continent including peninsular advanced neolithic/Chalco eastern mountain and the allu- India. lithic and vial plain of the ganges. They continuously flooded the 5. Urbanisation or Bronze age. People began to make ‘special- Indian subcontinent in waves of Paleolithic Age ized tools’ by flaking stones, migration from what is present which were pointed on one end. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

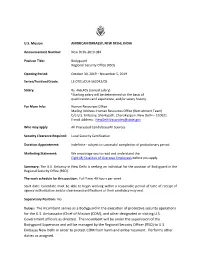

Duties: the Incumbent Serves As a Bodyguard in the Execution of Protective Security Operations for the U.S

U.S. Mission AMERICAN EMBASSY, NEW DELHI, INDIA Announcement Number: New Delhi-2019-084 Position Title: Bodyguard Regional Security Office (RSO) Opening Period: October 30, 2019 – November 5, 2019 Series/Position/Grade: LE-0701 /DLA-562042/05 Salary: Rs. 466,405 (annual salary) *Starting salary will be determined on the basis of qualifications and experience, and/or salary history. For More Info: Human Resources Office Mailing Address: Human Resources Office (Recruitment Team) C/o U.S. Embassy, Shantipath, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. E-mail Address: [email protected] Who may apply: All Interested Candidates/All Sources Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification Duration Appointment: Indefinite - subject to successful completion of probationary period Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi is seeking an individual for the position of Bodyguard in the Regional Security Office (RSO). The work schedule for this position: Full Time; 40 hours per week Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent serves as a Bodyguard in the execution of protective security operations for the U.S. Ambassador/Chief of Mission (COM), and other designated or visiting U.S. Government officials as directed. The incumbent will be under the supervision of the Bodyguard Supervisor and will be managed by the Regional Security Officer (RSO) to U.S. Embassy New Delhi in order to protect COM from harm and embarrassment. -

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great 356 – 323 B.C. 1. Macedonia, Greece 2. Father – Philip II, King of Macedonia Alexander died at the age of 33 3. Macedonia was very wealthy during the time of King Philip and Alexander. 4. In 357 B.C. Philip at the age of 26 married Olympias of Epirus, not a Macedonian, and in 356 B.C. she gave birth to Alexander. 5. Philip saw her in bed with a snake and wondered as to who was the father of this child, Philip or Zeus. Many times Zeus presented himself in Greek mythology as a snake. 6. Pella, the town where Alexander was born and raised. 7. Aigai, the historic capital of Macedonia. 8. Homer, Alexander’s favorite author. 9. Aristotle, Alexander’s teacher. 10. Hephaestion, Alexander’s closest friend. 11. Pike, a Greek lance 15‐18 feet long. 12. Alexander, at the age of 18, showed his military abilities in 338 B.C. in the Battle of Chaeronea which was between the armies of Macedonia and Athens/Thebes. Alexander was in charge of the cavalry which destroyed the Thebans. 13. In 338 B.C. Philip married 20 year old Cleopatra, a Macedonian. A son by Cleopatra would replace Alexander as the next King of Macedonia. Later Cleopatra gave birth to a son. 14. At the wedding feast in 338 B.C. Philip tried to kill Alexander but failed. Alexander and Olympias then went into exile. Alexander returned to Macedonia but a rift continued to exist between Alexander and Philip. 15. Philip’s vision at this time was to go to war against Darius, King of Persia. -

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period.