Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

Henry Andrews Bumstead 1870-1920

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XIII SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF HENRY ANDREWS BUMSTEAD 1870-1920 BY LEIGH PAGE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1929 HENRY ANDREWS BUMSTEAD BY LIUGH PAGE Henry Andrews Bumstead was born in the small town of Pekin, Illinois, on March 12th, 1870, son of Samuel Josiah Bumstead and Sarah Ellen Seiwell. His father, who was a physician of considerable local prominence, had graduated from the medical school in Philadelphia and was one of the first American students of medicine to go to Vienna to complete his studies. While the family was in Vienna, Bumstead, then a child three years of age, learned to speak German as fluently as he spoke English, an accomplishment which was to prove valuable to him in his subsequent career. Bumstead was descended from an old New England family which traces its origin to Thomas Bumstead, a native of Eng- land, who settled in Boston, Massachusetts, about 1640. Many of his ancestors were engaged in the professions, his paternal grandfather, the Reverend Samuel Andrews Bumstead, being a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary and a minister in active service. From them he inherited a keen mind and an unusually retentive memory. It is related that long before he had learned to read, his Sunday school teacher surprised his mother by complimenting her on the ease with which her son had rendered the Sunday lesson. It turned out that his mother made a habit of reading the lesson to Bumstead before he left for school, and the child's remarkable performance there was due to his ability to hold in his memory every word of the lesson after hearing it read to him a single time. -

Josiah Willard Gibbs

GENERAL ARTICLE Josiah Willard Gibbs V Kumaran The foundations of classical thermodynamics, as taught in V Kumaran is a professor textbooks today, were laid down in nearly complete form by of chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Josiah Willard Gibbs more than a century ago. This article Science, Bangalore. His presentsaportraitofGibbs,aquietandmodestmanwhowas research interests include responsible for some of the most important advances in the statistical mechanics and history of science. fluid mechanics. Thermodynamics, the science of the interconversion of heat and work, originated from the necessity of designing efficient engines in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Engines are machines that convert heat energy obtained by combustion of coal, wood or other types of fuel into useful work for running trains, ships, etc. The efficiency of an engine is determined by the amount of useful work obtained for a given amount of heat input. There are two laws related to the efficiency of an engine. The first law of thermodynamics states that heat and work are inter-convertible, and it is not possible to obtain more work than the amount of heat input into the machine. The formulation of this law can be traced back to the work of Leibniz, Dalton, Joule, Clausius, and a host of other scientists in the late 17th and early 18th century. The more subtle second law of thermodynamics states that it is not possible to convert all heat into work; all engines have to ‘waste’ some of the heat input by transferring it to a heat sink. The second law also established the minimum amount of heat that has to be wasted based on the absolute temperatures of the heat source and the heat sink. -

A Conversation with Richard A. Olshen 3

Statistical Science 2015, Vol. 30, No. 1, 118–132 DOI: 10.1214/14-STS492 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2015 A Conversation with Richard A. Olshen John A. Rice Abstract. Richard Olshen was born in Portland, Oregon, on May 17, 1942. Richard spent his early years in Chevy Chase, Maryland, but has lived most of his life in California. He received an A.B. in Statistics at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1963, and a Ph.D. in Statistics from Yale University in 1966, writing his dissertation under the direction of Jimmie Savage and Frank Anscombe. He served as Research Staff Statistician and Lecturer at Yale in 1966–1967. Richard accepted a faculty appointment at Stanford University in 1967, and has held tenured faculty positions at the University of Michigan (1972–1975), the University of California, San Diego (1975–1989), and Stanford University (since 1989). At Stanford, he is Professor of Health Research and Policy (Biostatistics), Chief of the Division of Biostatistics (since 1998) and Professor (by courtesy) of Electrical Engineering and of Statistics. At various times, he has had visiting faculty positions at Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Stanford and the Hebrew University. Richard’s research interests are in statistics and mathematics and their applications to medicine and biology. Much of his work has concerned binary tree-structured algorithms for classification, regression, survival analysis and clustering. Those for classification and survival analysis have been used with success in computer-aided diagnosis and prognosis, especially in cardiology, oncology and toxicology. He coauthored the 1984 book Classi- fication and Regression Trees (with Leo Brieman, Jerome Friedman and Charles Stone) which gives motivation, algorithms, various examples and mathematical theory for what have come to be known as CART algorithms. -

Statement by Howard Bloch at the FAS Senate Meeting on October 15, 2020 Missed Opportunities

Statement by Howard Bloch at the FAS Senate meeting on October 15, 2020 Missed Opportunities So much of what goes into making a university great has to do with meeting and matching the moment. Science at Yale began with such a recognition. When a meteorite fell on the morning of December 14, 1807 in Weston, CT, an enterprising young Professor of Chemistry, Benjamin Silliman, and a colleague, James Kingsley, who taught Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, set off two days later to bring it back to New Haven. The paper which Silliman presented to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia in 1809 engendered a national debate and was probably the first scientific paper in America since those of Benjamin Franklin to attract notice in Europe. When it came to the natural sciences, Yale was unsurpassed by any American university in the nineteenth century, which began with Silliman and ended with Josiah Willard Gibbs whom Albert Einstein, leaving all relativity aside, pronounced “the greatest mind in American history.” But science lagged at Yale in the twentieth century, in part as a result of missed opportunities. Yale failed to hire Jewish scientists exiled from Germany and Hungary in the wake of the rise of Nazism in the 1930s and 40s. None of the exiled physicists who played major and supporting roles in the quantum revolution, Jewish or not, ended up in New Haven, but were welcomed at Princeton/IAS, Columbia, Harvard, MIT, Cornell, the University of Chicago, UC-Berkeley, and Caltech. When we missed the revolution in physics in the first half of the century, we were ill-suited to participate in the revolution in genetics in the second half. -

Slepian-UF-Q2-On the Nature of Time and Being-Gen Ed Syllabus

Quest 2: On the nature of time and being: an astrophysics-informed approach to the big questions Primary General Education Designation: Physical Sciences Secondary General Education Designation: International I. Course Information Quest 2 IDS2935/XXXX, Spring 2020 Meeting Day/Time: TBA Location: TBA General Education Designation: [Physical Sciences, International, WR 4000] * A minimum grade of C is required for general education credit * Instructor Zachary Slepian, PhD [email protected]; (352) 294–1851 Office Hours: Days TBD, Time TBD 302 Bryant Space Science Center Course Description What is the nature of time? What is the nature of space (and space-time)? And where do we fit in? These are hard questions, and this course will not offer final answers. Rather, in this course we will acquire the tools and language to think critically about these questions. We will thoroughly investigate some of the most interesting topics in contemporary physics— the arrow of time, irreversibility, quantum mechanics, cosmology—through the lens of these big questions. Throughout, we will attack these areas via many different channels. This class should be accessible to non-physics majors—indeed, to those with minimal technical background at all—so we will focus on the concepts, exploring the key ideas with almost no math. At the same time, we will mix in ideas from philosophy, history, and art that also bear on these questions. This will make the course relevant and exciting both for those who feel a strong affinity with the arts and humanities as well as for those for whom science resonates more. 1 Importantly, the course will also expose what the scientific method is and how science has been shaped by broader currents in history, culture, and philosophy, and in turn, how it has shaped them. -

Yale University Catalogue, 1860 Yale University

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale University Catalogue Yale University Publications 1860 Yale University Catalogue, 1860 Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue Recommended Citation Yale University, "Yale University Catalogue, 1860" (1860). Yale University Catalogue. 49. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Yale University Publications at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale University Catalogue by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATALOGUE OF THE OFFICERS AND STUDENTS IN YALE COLLEGE, WITH A STATEMENT OF THE COURSE OF INSTRUCTION IN THE VARIOUS DEPARTMENTS. 1860-61. P It IX TED BY E. H ~YES, 426 C II APEL T. 1860. 2 THE GOVERNOR, LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR, AND SIX SENIOR SENATORS OF THE STATE ARE, ex officio, )(EMBERS OF THE CORPORATION. PB.ESJ:DENT. REv. THEODORE D. WOOLSEY, D. D., LL. D. FELLOWS.• Hrs Exe. WILLIAM A. BUCKINGHAM, NoRWICH. His IloNoR JULIUS CATLIN, HARTFORD. REv. DAVID SMITH, D. D., DuanAl'tl. REV. NOAH PORTER, D. D., FARl\IINGTON. REV. JEREMIAH DAY, D. D., LL. D., NEW HAVEN. REV. JOEL HAWES, D. D., HARTFORD. REV. JOSEPH ELDRIDGE, D. D., NORFOLK. REV. GEORGE A. CALHOUN, D. D., COVENTRY. REv. GEORGE J. TILLOTSON, PuTNAl\l. REV. EDWIN R. GILBERT, WALLINGFORD. REV. JOEL H. LINSLEY, D. D., GREENWICH. HoN. ELISHA JOHNSON, HARTFORD. HoN. JOHN W. -

View This Volume's Front and Back Matter

Titles in This Series Volume 8 Kare n Hunger Parshall and David £. Rowe The emergenc e o f th e America n mathematica l researc h community , 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moore 1994 7 Hen k J. M. Bos Lectures in the history of mathematic s 1993 6 Smilk a Zdravkovska and Peter L. Duren, Editors Golden years of Moscow mathematic s 1993 5 Georg e W. Mackey The scop e an d histor y o f commutativ e an d noncommutativ e harmoni c analysis 1992 4 Charle s W. McArthur Operations analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War II 1990 3 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part III 1989 2 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part II 1989 1 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part I 1988 This page intentionally left blank https://doi.org/10.1090/hmath/008 History of Mathematics Volume 8 The Emergence o f the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moor e Karen Hunger Parshall David E. Rowe American Mathematical Societ y London Mathematical Societ y 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A55 , 01A72, 01A73; Secondary 01A60 , 01A74, 01A80. Photographs o n th e cove r ar e (clockwis e fro m right ) th e Gottinge n Mathematisch e Ges - selschafft, Feli x Klein, J. J. Sylvester, and E. H. Moore. -

The One Hundred and Fifth Presentation of the Willard Gibbs Medal (Founded by William A

Chicago Section http://chicagoacs.org MAY • 2016 THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTH PRESENTATION OF THE WILLARD GIBBS MEDAL (FOUNDED BY WILLIAM A. CONVERSE) TO PROFESSOR LAURA KIESSLING SPONSORED BY THE CHICAGO SECTION OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY FRIDAY, MAY 20, 2016 Meridian Banquets 1701 Algonquin Road Rolling Meadows, IL 60008 847-952-8181 DIRECTIONS TO THE MEETING From Chicago: Take I-90 west to Arlington Heights Road. Exit north to the first light, Algonquin Rd., Route 62, turn left/west and travel to Meridian Banquets on the left. From I-294 North/South Take I-294 north or south to the I-90 junction near O’Hare. Travel west on I-90 and follow the directions above. From I-290/I-355/Route 53: Travel north past I-90 as 355 turns into 53. Exit Algonquin Rd., Rt. 62 east and go to Meridian Banquets on the right. ON-SITE PARKING: Free Dr. Laura Kiessling, Steenbock IN THIS ISSUE Professor of Chemistry, Laurens Anderson Professor of Biochemistry, 2 Kiessling Biography 5 A Company You Should Know Director of the Keck Center for Chemical 2 Menu 6 ChemShorts Genomics, University of Wisconsin - 2 Calendar 6 Fran Kravitz Wins Boy Scout of Madison 3 Willard Gibbs Award America Silver Beaver Award 3 Micron Analytical Services 6 Report of the ACS Council Chemical Probes of Immunity and 4 Someone You Should Know 7 Mass-Vac Products Tolerance 4 Volunteers Needed For State Fair (continued on page 2) (continued from page 1) DINNER MENU The Chicago Section’s The Citation – For pioneering research • Cream of Tomato Basil with Bleu in chemical biology, including insights e-mail address Cheese into intercellular communication in is • Meridian Salad bacteria and eukaryotes and elucidation [email protected] • Wine of carbohydrate-mediated cell-surface • Choice of entree: interactions. -

NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES July 1, 1960 OFFICERS Term Expires President-Detlev W

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES July 1, 1960 OFFICERS Term expires President-Detlev W. Bronk June 30, 1962 Vice President-Farrington Daniels June 30, 1961 Home Secretary-Hugh L. Dryden June 30, 1963 Foreign Secretary-H. P. Robertson June 30, 1962 Treasurer-L. V. Berkner June 30, 1964 Executive Officer Business Manager S. D. Cornell G. D. Meid COUNCIL Adams, Roger (1962) *Houston, W. V. (1962) *Berkner, L. V. (1964) Hutchinson, G. Evelyn (1963) *Bronk, Detlev W. (1962) Mac Lane, Saunders (1961) *Daniels, Farrington (1961) *Robertson, H. P. (1962) *Dryden, Hugh L. (1963) Williams, Robley C. (1963) *Francis, Thomas, Jr. (1961) MEMBERS The number in parentheses, following year of election, indicates the Section to which the member belongs, as follows: (1) Mathematics (8) Zoology and Anatomy (2) Astronomy (9) Physiology (3) Physics (10) Pathology and Microbiology (4) Engineering (11) Anthropology (5) Chemistry (12) Psychology (6) Geology (13) Geophysics (7) Botany (14) Biochemistry Abbot, Charles Greeley, 1915 (2), Smithsonian Institution, Washington 25, D. C. Abelson, Philip Hauge, 1959 (6), Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 2801 Upton Street, N. W., Washington 8, D. C. Adams, Leason Heberling, 1943 (13), Institute of Geophysics, University of California, Los Angeles 24, California Adams, Roger, 1929 (5), Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois Ahlfors, Lars Valerian, 1953 (1), Department of Mathematics, Harvard University, 2 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge 38, Massachusetts Albert, Abraham Adrian, 1943 (1), Department of Mathematics, University of Chicago, Chicago 37, Illinois Albright, William Foxwell, 1955 (11), Oriental Seminary, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore 18, Maryland Alexander, James Waddell, 1930 (1), 29 Cleveland Lane, Princeton, New Jersey * Members of the Executive Committee of the Council of the Academy. -

Turbulent Flows on Complex Networks

2162-8 Advanced Workshop on Anderson Localization, Nonlinearity and Turbulence: a Cross-Fertilization 23 August - 3 September, 2010 Turbulent flows on complex networks Dima SHEPELYANSKY Univ. Paul Sabatier, Lab. Physique Theorique IRSAMC Toulouse France Turbulent flows on complex networks Dima Shepelyansky (CNRS, Toulouse) www.quantware.ups-tlse.fr/dima Collaboration: A.D.Chepelianskii, L.Ermann, B.Georgeot, O.Giraud (CNRS, France) A.O.Zhirov, O.V.Zhirov (NSU - BINP, Novosibirsk) “Through mechanisms still only partially understood, wind transfers energy and momentum to surface water waves.” A.C.Newell and V.E.Zakharov (PRL 1992) Through mechanisms still only partially understood, Google finds instantaneously the page you need. Story started in 1998 (now N ∼ 1011 nodes) S. Brin and L. Page, Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 30,107 (1998). (Quantware group, CNRS, Toulouse) ICTP, Trieste August 25, 2010 3 / 21 How Google works Directed networks Weighted adjacency matrix ⎛ ⎞ 2 0000000 ⎜ 1 ⎟ ⎜ 3 000000⎟ ⎜ 1 1 ⎟ 1 ⎜ 00 000⎟ 3 67 ⎜ 3 2 ⎟ S = ⎜ 1 000111⎟ ⎜ 3 ⎟ ⎜ 0001 000⎟ 5 4 ⎝ 2 ⎠ 0100000 0000000 For a directed network with N nodes the adjacency matrix A is defined as Aij = 1 if there is a link from node j to node i and Aij = 0 otherwise. The weighted adjacency matrix is Sij = Aij / Akj k In addition the elements of columns with only zeros elements are replaced by 1/N. (Quantware group, CNRS, Toulouse) ICTP, Trieste August 25, 2010 4 / 21 How Google works Google Matrix and Computation of PageRank p = Sp ⇒ p= stationary vector of S; can be computed by iteration of S. -

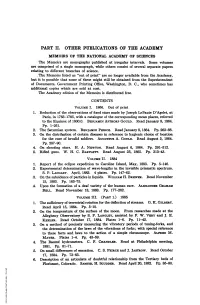

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2.