The Case for Reparations: the Social Gospel of Walter Rauschenbusch and a Program to Understand and Close the Racial Wealth Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Garveyism: a ’90S Perspective Francis E

New Directions Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 7 4-1-1991 Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective Francis E. Dorsey Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections Recommended Citation Dorsey, Francis E. (1991) "Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective," New Directions: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol18/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Directions by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GARVEYISM A ’90s Perspective By Francis E. Dorsey Pan African Congress in Manchester, orn on August 17, 1887 in England in 1945 in which the delegates Jamaica, Marcus Mosiah sought the right of all peoples to govern Garvey is universally recog themselves and freedom from imperialist nized as the father of Pan control whether political or economic. African Nationalism. After Garveyism has taught that political power observing first-hand the in without economic power is worthless. Bhumane suffering of his fellow Jamaicans at home and abroad, he embarked on a mis The UNIA sion of racial redemption. One of his The corner-stone of Garvey’s philosophical greatest assets was his ability to transcend values was the establishment of the Univer myopic nationalism. His “ Back to Africa” sal Negro Improvement Association, vision and his ‘ ‘Africa for the Africans at UNIA, in 1914, not only for the promulga home and abroad” geo-political perspec tion of economic independence of African tives, although well before their time, are peoples but also as an institution and all accepted and implemented today. -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

Black Capitalism’

Opinion The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism’ Nixon’s solution for racial ghettos was tax breaks and incentives, not economic justice. By Mehrsa Baradaran March 31, 2019 The tax bill President Trump signed into law in 2017 created an “opportunity zones” program, the details of which will soon be finalized. The program will provide tax cuts to investors to spur development in “economically distressed” areas. Republicans and Democrats stretching back to the Nixon administration have tried ideas like this and failed. These failures are well known, but few know the cynical and racist origins of these programs. The neighborhoods labeled “opportunity zones” are “distressed” because of forced racial segregation backed by federal law — redlining, racial covenants, racist zoning policies and when necessary, bombs and mob violence. These areas were black ghettos. So how did they come to be called “opportunity zones?” The answer lies in “black capitalism,” a forgotten aspect of Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Mr. Nixon's solution for racial ghettos was not economic justice, but tax breaks and incentives. This deft political move allowed him to secure the support of 2 white Southerners and to oppose meaningful economic reforms proposed by black activists. You can see how clever that political diversion was by looking at the reforms that were not carried out. After the Civil Rights Act, black activists and their allies pushed the federal government for race-specific economic redress. The “whites only” signs were gone, but joblessness, dilapidated housing and intractable poverty remained. In 1967, blacks had one-fifth the wealth of white families. ADVERTISEMENT Yet a white majority opposed demands for reparations, integration and even equal resources for schools. -

2020 Tournament Distributed Packet

Loomis Chaffee Debate Tournament – Resolution & Information packet Jan. 2020 Resolved, that the United States should adopt a program of reparations to redress the harms caused by historic, systemic racist policies, including slavery. Redress = to remedy or compensate for a wrong or grievence From the International Center for Transitional Justice Website “Overview of Reparations” Reparations serve to acknowledge the legal obligation of a state, or individual(s) or group, to repair the consequences of violations — either because it directly committed them or it failed to prevent them. They also express to victims and society more generally that the state is committed to addressing the root causes of past violations and ensuring they do not happen again. With their material and symbolic benefits, reparations are important to victims because they are often seen as the most direct and meaningful way of receiving justice. Yet, they are often the last-implemented and least-funded measure of transitional justice. It is important to remember that financial compensation — or the payment money — is only one of many different types of material reparations that can be provided to victims. Other types include restoring civil and political rights, erasing unfair criminal convictions, physical rehabilitation, and granting access to land, health care, or education. Sometimes, these measures are provided to victims’ family members, often children, in recognition that providing them with a better future is an important way to overcome the enduring consequences of the violations. Reparations can be implemented through administrative programs or enforced as the outcome of litigation. Oftentimes, they overlap and compete for state resources with programs against poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to resources, like land. -

The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates - the Atlantic

3/22/2016 The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates - The Atlantic The Case for Reparations Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole. Carlos Javier Ortiz T A - N E H I S I C O A T E S TEXT SIZE J U N E 2 0 1 4 I S S U E | B U S I N E S S And if thy brother, a Hebrew man, or a Hebrew woman, be sold unto thee, and serve thee six years; then in the seventh year thou shalt let him go free from thee. And when thou sendest him out free from thee, thou shalt not let him go away empty: thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the LORD thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him. And thou shalt remember that thou wast a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the LORD thy God redeemed thee: therefore I command thee http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/ 1/63 3/22/2016 The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates - The Atlantic this thing today. — DEUTERONOMY 15: 12–15 Besides the crime which consists in violating the law, and varying from the right rule of reason, whereby a man so far becomes degenerate, and declares himself to quit the principles of human nature, and to be a noxious creature, there is commonly injury done to some person or other, and some other man receives damage by his transgression: in which case he who hath received any damage, has, besides the right of punishment common to him with other men, a particular right to seek reparation. -

American Catholics Radical Response to the Social Gospel Movement and Progressives

Journal of Catholic Education Volume 24 Issue 1 Article 5 7-2021 Social Reconstruction: American Catholics Radical Response to the Social Gospel Movement and Progressives. Paul Lubienecki, PhD Boland Center for the Study of Labor and Religion Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ce Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Labor History Commons, Other Education Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lubienecki, PhD, P. (2021). Social Reconstruction: American Catholics Radical Response to the Social Gospel Movement and Progressives.. Journal of Catholic Education, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.15365/ joce.2401052021 This Article is brought to you for free with open access by the School of Education at Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for publication in Journal of Catholic Education by the journal's editorial board and has been published on the web by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information about Digital Commons, please contact [email protected]. To contact the editorial board of Journal of Catholic Education, please email [email protected]. Social Reconstruction 83 Journal of Catholic Education Spring 2021, Volume 24, Issue 1, 83-106 This work is licensed under CCBY 4.0. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.2401052021 Social Reconstruction: American Catholics’ Radical Response to the Social Gospel Movement and Progressives Paul Lubienecki1 Abstract: At the fin de siècle the Industrial Revolution created egregious physical, emotional and spiritual conditions for American society and especially for the worker but who would come forward to alleviate those conditions? Protestants implemented their Social Gospel Movement as a pro- posed cure to these problems. -

Mainline Church Renewal and the Union Corporate Campaign

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by St. John's University School of Law Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 50 Number 1 Volume 50, 2011, Numbers 1&2 Article 9 March 2017 Steeple Solidarity: Mainline Church Renewal and the Union Corporate Campaign Michael M. Oswalt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Michael M. Oswalt (2011) "Steeple Solidarity: Mainline Church Renewal and the Union Corporate Campaign," Journal of Catholic Legal Studies: Vol. 50 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls/vol50/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STEEPLE SOLIDARITY: MAINLINE CHURCH RENEWAL AND THE UNION CORPORATE CAMPAIGN MICHAEL M. OSWALTt INTRODUCTION Having finished his afternoon coffee, Reverend Dick Gillett arose from his table to speak.' Others who were scattered throughout the Century Plaza hotel's dining room quietly rose with him, many similarly dressed in unmistakably religious attire.2 "We know this is a bit unusual," Gillett began, "but we want you to know that the people who have prepared your meals and who wait on you so efficiently and courteously want your help today. And you could help them, just by asking for the manager and telling him you'd like this hotel to sign the contract."3 What might have been unusual for the diners was not unusual for this group of sixty activists, driven by faith to support Los Angeles hotel workers. -

TPHFM-Spring-Edition

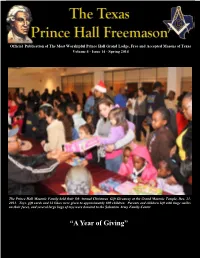

Official Publication of The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons of Texas Volume 4 - Issue 14 - Spring 2014 The Prince Hall Masonic Family held their 5th Annual Christmas Gift Giveaway at the Grand Masonic Temple, Dec. 21, 2013. Toys, gift cards and 32 bikes were given to approximately 800 children. Parents and children left with huge smiles on their faces, and several large bags of toys were donated to the Salvation Army Family Center. “A Year of Giving” Table of Contents Grand Master’s Message………………... 3 The Texas Prince Hall Freemason Grand Master’s Calendar..………….…... 5 MLK March Photos…………………….. 7 Publisher 5th Annual Christmas Gift Giveaway…... 8 M.W. Wilbert M. Curtis Mid-Winter Session…………………….. 11 K.O.P……………………………………. 14 Editor District Activities……………………….. 18 W.M. Burrell D. Parmer Spotlight………………………………… 47 Adopted, Appendant and Concordant Publications Committee 48 Bodies………………………………….... Chairman/Layout & Design, W.M. Burrell D. Parmer Lodge of Research ……………………... 68 Layout & Design, P.M. Edward S. Jones Forum…………………………………… 73 Sons of Solomon Motorcycle Club……... 74 Copy Editor, P.M. Frederic Milliken Copy Editor, P.M. Burnell White Jr. Copy Editor, W.M. Broderick James From the Editor Photography, P.M. Bryan Thompson Greetings, Webmaster, P.M. Clary Glover Jr. Another year has passed. Did you accomplish your goals? Grand Lodge Officers Did you improve upon your- 2013 - 2014 self, family, community, and Lodge. What is going to be Grand Master different in your life this M.W. Wilbert M. Curtis 2014? How are you planning to use your Working Tools Past Grand Master this year? Again it is an honor and pleasure to bring to you the 14th edition of The Texas Hon. -

PEGODA-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (3.234Mb)

© Copyright by Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS ____________________________ Andrew Joseph Pegoda APPROVED: ____________________________ Linda Reed, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. ____________________________ Richard Mizelle, Ph.D. ____________________________ Barbara Hales, Ph.D. University of Houston-Clear Lake ____________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics ii “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ An Abstract of A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 ABSTRACT Historians have continued to expand the available literature on the Civil Rights Revolution, an unprecedented social movement during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s that aimed to codify basic human and civil rights for individuals racialized as Black, by further developing its cast of characters, challenging its geographical and temporal boundaries, and by comparing it to other social movements both inside and outside of the United States. -

The Case for Reparations MENU

FEATURES: The Case for Reparations MENU Carlos Javier Ortiz The Case for Reparations Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole. By Ta-Nehisi Coates MAY 21, 2014 nd if thy brother, a Hebrew man, or a Hebrew woman, be sold unto thee, and serve thee six years; then in the seventh year thou shalt let him go A free from thee. And when thou sendest him out free from thee, thou shalt Chapters not let him go away empty: thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and I. “So That’s Just One Of My out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the LORD thy God Losses” hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him. And thou shalt remember that thou II. “A Difference of Kind, Not wast a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the LORD thy God redeemed thee: Degree” therefore I command thee this thing today. III. “We Inherit Our Ample Patrimony” — DEUTERONOMY 15: 12–15 IV. “The Ills That Slavery Frees Us From” Besides the crime which consists in violating the law, and varying from the right V. The Quiet Plunder rule of reason, whereby a man so far becomes degenerate, and declares himself to quit the principles of human nature, and to be a noxious creature, there is VI. Making The Second Ghetto commonly injury done to some person or other, and some other man receives VII.