Common Interests, Competing Subjectivities: Us and Latin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stan Brakhage

DAVID E. JAMES Introduction Stan Brakhage The Activity of His Nature Milton produced Paradise Lost for the same reason that a silk worm produces silk. It was an activity of his nature.—KARL MARX ork on this collection of texts began some three years ago, when we hoped to publish it in 2003 to celebrate Stan Brakhage’s Wseventieth birthday. Instead, belatedly, it mourns his death. The baby who would become James Stanley Brakhage was born on 14 January 1933 in an orphanage in Kansas City, Missouri.1 He was adopted and named by a young couple, Ludwig, a college teacher of business, and his wife, Clara, who had herself been raised by a stepmother. The family moved from town to town in the Middle West and, sensitive to the stresses of his parents’ unhappy marriage, Stanley was a sickly child, asthmatic and over- weight. His mother took a lover, eventually leaving her husband, who sub- sequently came to terms with his homosexuality and also himself took a lover. In 1941, mother and son found themselves alone in Denver. Put in a boys’ home, the child picked up the habits of a petty criminal, but before his delinquency became serious, he was placed with a stable, middle-class family in which he began to discover his gifts. He excelled in writing and dramatics and in singing, becoming one of the leading voices in the choir of the Cathedral of St. John’s in Denver. Retrieving her now-teenaged son, his mother tried to make a musician of him, but Stanley resisted his tutors, even attempting to strangle his voice teacher. -

Entretien Avec Fernando Solanas : La Déchirure

Document generated on 09/29/2021 5:14 p.m. 24 images Entretien avec Fernando Solanas La déchirure Janine Euvrard Cinéma et exil Number 106, Spring 2001 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/23987ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Euvrard, J. (2001). Entretien avec Fernando Solanas : la déchirure. 24 images, (106), 33–38. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 2001 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CINÉMA ET EXIL Entretien avec Fernando Solanas LA DÉCHIRURE PROPOS RECUEILLIS PAR JANINE EUVRARD 24 IMAGES: Au mot exil dans le Petit Larousse, on lit «expulsion». Ce n'est pas toujours le cas; parfois la personne prend les devants et part avant d'être expulsée. Pouvez-vous nous raconter votre départ d'Argentine? Il est des cinéastes pour qui la vie, la création, le rapport FERNANDO SOLANAS: Votre question est intéressante. Il y a au pays et le combat politique sont viscéralement indisso souvent confusion, amalgame, lorsqu'on parle de gens qui quittent leur pays sans y être véritablement obligés, sans y être vraiment en ciables. -

Fernando A. Blanco Wittenberg University & John Petrus the Ohio

REVISTA DE CRÍTICA LITERARIA LATINOAMERICANA Año XXXVII, No 73. Lima-Boston, 1er semestre de 2011, pp. 307-331 ARGENTINIAN QUEER MATER. DEL BILDUNGSROMAN URBANO A LA ROAD MOVIE RURAL: INFANCIA Y JUVENTUD POST-CORRALITO EN LA OBRA DE LUCÍA PUENZO Fernando A. Blanco Wittenberg University & John Petrus The Ohio State University Resumen En este artículo analizamos la obra visual y literaria de la directora y narradora argentina Lucía Puenzo en su excepcionalidad estética y ética. Mediante un análisis de dos de sus películas, XXY y El niño pez, basadas en un cuento y una novela, discutimos la apropiación de géneros canónicos de ambas tradiciones –Bildungsroman y road movie– como estrategia de instalación generacional. Por medio del recurso a estos modelos formativos de la subjetividad, Puenzo logra posicionar alternativas identitarias refractarias a la normalización heterosexual de lo nacional-popular en el campo cultural argentino. Trabajando desde una clave de interpretación diferente de la de los relatos de memoria en la post democracia neoliberal, Puenzo sitúa problemáticas adolescentes en el entre- cruzamiento de modos y maneras excéntricos de habitar lo social-global en el capitalismo tardío. Sus filmes, de este modo, abren la posibilidad de reflexionar sobre el derecho a ciudadanías culturales, étnicas y sexuales de grupos minoritarios. Palabras clave: Puenzo, Bildungsroman, road movie, sujeto queer, parodia, memoria, Argentina, literatura, cine. Abstract In this article we analyze the exceptional ethics and aesthetics of the visual and literary work of the Argentine writer-director Lucía Puenzo. Through an analysis of two of her films, XXY and The Fish Child, based on a short story and a novel, respectively, we discuss her appropriation of canonical genres–the Bildungsroman and the road movie–as a strategy of generational displacement. -

Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films

Travelling Films: Western Criticism, Labelling Practice and Self-Orientalised East Asian Films Goldsmiths College University of London PhD thesis (Cultural Studies) Ji Yeon Lee Abstract This thesis analyses western criticism, labelling practices and the politics of European international film festivals. In particular, this thesis focuses on the impact of western criticism on East Asian films as they attempt to travel to the west and when they travel back to their home countries. This thesis draws on the critical arguments by Edward Said's Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (1978) and self-Orientalism, as articulated by Rey Chow, which is developed upon Mary Louise Pratt's conceptual tools such as 'contact zone' and 'autoethnography'. This thesis deals with three East Asian directors: Kitano Takeshi (Japanese director), Zhang Yimou (Chinese director) and 1m Kwon-Taek (Korean director). Dealing with Japanese, Chinese and Korean cinema is designed to show different historical and cultural configurations in which each cinema draws western attention. This thesis also illuminates different ways each cinema is appropriated and articulated in the west. This thesis scrutinises how three directors from the region have responded to this Orientalist discourse and investigates the unequal power relationship that controls the international circulation of films. Each director's response largely depends on the particular national and historical contexts of each country and each national cinema. The processes that characterise films' travelling are interrelated: the western conception of Japanese, Chinese or Korean cinema draws upon western Orientalism, but is at the same time corroborated by directors' responses. Through self-Orientalism, these directors, as 'Orientals', participate in forming and confirming the premises of western Orientalism. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

Imperialism and Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2016 Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College Recommended Citation Wright, Andy, "Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie" (2016). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 75. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/75 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright 1 OFF THE ROAD Imperialism And Exploration In The American Road Movie “Road movies are too cool to address serious socio-political issues. Instead, they express the fury and suffering at the extremities of a civilized life, and give their restless protagonists the false hope of a one-way ticket to nowhere.” –Michael Atkinson, quoted in “The Road Movie Book” (1). “‘Imperialism’ means the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory; ‘colonialism’, which is almost always a consequence of imperialism, is the implanting of settlements on distant territory” –Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (9) “I am still a little bit scared of flying, but I am definitely far more scared of all the disgusting trash in between places” -Cy Amundson, This Is Not Happening “This is gonna be exactly like Eurotrip, except it’s not gonna suck” -Kumar Patel, Harold and Kumar Escape From Guantanamo Bay Wright 2 Off The Road Abstract: This essay explores the imperialist nature of the American road movie as it is defined by the film’s era of release, specifically through the lens of how road movies abuse the lands that are travelled through. -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Stan Brakhage 12/28/07 10:25 PM

Stan Brakhage 12/28/07 10:25 PM contents great directors cteq annotations top tens about us links archive search Stan Brakhage b. January 14, 1933, Kansas City, Missouri, USA d. March 9, 2003, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada by Brian Frye Brian Frye is a filmmaker, curator and writer living in Washington DC. filmography bibliography articles in Senses web resources If Maya Deren invented the American avant-garde cinema, Stan Brakhage realized its potential. Unquestionably the most important living avant-garde filmmaker, Brakhage single-handedly transformed the schism separating the avant-garde from classical filmmaking into a chasm. And the ultimate consequences have yet to be resolved; his films appear nearly as radical today as the day he made them. Brakhage was born in 1933, and made his first film, Interim (1952), at 19. Notably prolific, he has completed several films most years since. To date, his filmography lists over 300 titles, ranging in length from a few seconds to several hours. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, attended high school in Central City, Colorado. He briefly attended Dartmouth College then left for San Francisco, where he enrolled at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute). He had hoped to study under Sidney Peterson., but unfortunately, Peterson had left the school and the film program was no more, so Brakhage moved on. Like Deren, Brakhage came to understand film through poetry, and his earliest films do resemble those of Deren and her contemporaries. The early American avant-garde filmmakers tended to borrow liberally from the German Expressionists and Surrealists: mannered acting, symbolism/non sequitur, non-naturalistic lighting and psychosexual themes were common. -

Experimental Film

source guides experimental film National Library experimental film 16 + Source Guide contents THE CONTENTS OF THIS PDF CAN BE VIEWED QUICKLY BY USING THE BOOKMARKS FACILITY INFORMATION GUIDE STATEMENT . .i BFI NATIONAL LIBRARY . .ii ACCESSING RESEARCH MATERIALS . .iii APPROACHES TO RESEARCH, by Samantha Bakhurst . .iv INTRODUCTION . .1 GENERAL REFERENCES . .1 FOCUS ON: DEREK JARMAN . .4 CHRIS MARKER . .6 MARGARET TAIT . .10 CASE STUDIES: ANGER, BRAKHAGE, AND WARHOL . .12 KENNETH ANGER . .13 STAN BRAKHAGE . .17 ANDY WARHOL . .23 Compiled by: Christophe Dupin Stephen Gordon Ayesha Khan Peter Todd Design/Layout: Ian O’Sullivan Project Manager: David Sharp © 2004 BFI National Library, 21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN 16+ MEDIA STUDIES INFORMATION GUIDE STATEMENT “Candidates should note that examiners have copies of this guide and will not give credit for mere reproduction of the information it contains. Candidates are reminded that all research sources must be credited”. BFI National Library i BFI National Library All the materials referred to in this guide are available for consultation at the BFI National Library. If you wish to visit the reading room of the library and do not already hold membership, you will need to take out a one-day, five-day or annual pass. Full details of access to the library and charges can be found at: www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo/library BFI National Library Reading Room Opening Hours: Monday 10.30am - 5.30pm Tuesday 10.30am - 8.00pm Wednesday 1.00pm - 8.00pm Thursday 10.30am - 8.00pm Friday 10.30am - 5.30pm If you are visiting the library from a distance or are planning to visit as a group, it is advisable to contact the Reading Room librarian in advance (tel. -

Will #Blacklivesmatter to Robocop?1

***PRELIMINARY DRAFT***3-28-16***DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION**** Will #BlackLivesMatter to Robocop?1 Peter Asaro School of Media Studies, The New School Center for Information Technology Policy, Princeton University Center for Internet and Society, Stanford Law School Abstract Introduction #BlackLivesMatter is a Twitter hashtag and grassroots political movement that challenges the institutional structures surrounding the legitimacy of the application of state-sanction violence against people of color, and seeks just accountability from the individuals who exercise that violence. It has also challenged the institutional racism manifest in housing, schooling and the prison-industrial complex. It was started by the black activists Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, following the acquittal of the vigilante George Zimmerman in the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2013.2 The movement gained momentum following a series of highly publicized killings of blacks by police officers, many of which were captured on video from CCTV, police dashcams, and witness cellphones which later went viral on social media. #BlackLivesMatter has organized numerous marches, demonstrations, and direct actions of civil disobedience in response to the police killings of people of color.3 In many of these cases, particularly those captured on camera, the individuals who are killed by police do not appear to be acting in the ways described in official police reports, do not appear to be threatening or dangerous, and sometimes even appear to be cooperating with police or trying to follow police orders. While the #BlackLivesMatter movement aims to address a broad range of racial justice issues, it has been most successful at drawing attention to the disproportionate use of violent and lethal force by police against people of color.4 The sense of “disproportionate use” includes both the excessive 1In keeping with Betteridge’s law of headlines, one could simply answer “no.” But investigating why this is the case is still worthwhile. -

Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

encounters ecstatic encounters ecstatic ecstatic encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Ecstatic Encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Layout: Maedium, Utrecht ISBN 978 90 8964 298 1 e-ISBN 978 90 4851 396 3 NUR 761 © Mattijs van de Port / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents PREFACE / 7 INTRODUCTION: Avenida Oceânica / 11 Candomblé, mystery and the-rest-of-what-is in processes of world-making 1 On Immersion / 47 Academics and the seductions of a baroque society 2 Mysteries are Invisible / 69 Understanding images in the Bahia of Dr Raimundo Nina Rodrigues 3 Re-encoding the Primitive / 99 Surrealist appreciations of Candomblé in a violence-ridden world 4 Abstracting Candomblé / 127 Defining the ‘public’ and the ‘particular’ dimensions of a spirit possession cult 5 Allegorical Worlds / 159 Baroque aesthetics and the notion of an ‘absent truth’ 6 Bafflement Politics / 183 Possessions, apparitions and the really real of Candomblé’s miracle productions 5 7 The Permeable Boundary / 215 Media imaginaries in Candomblé’s public performance of authenticity CONCLUSIONS Cracks in the Wall / 249 Invocations of the-rest-of-what-is in the anthropological study of world-making NOTES / 263 BIBLIOGRAPHY / 273 INDEX / 295 ECSTATIC ENCOUNTERS · 6 Preface Oh! Bahia da magia, dos feitiços e da fé. -

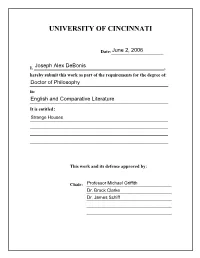

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Strange Houses A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 by Joseph Alex DeBonis B.A. Indiana University, 1996 M.A. Illinois State University, 2001 Committee Chair: Professor Michael Griffith Joseph Alex DeBonis Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, Strange Houses, is a collection of original short stories by the author, Joseph Alex DeBonis. The stories engage notions about home, family, estrangement, and alienation. Since many of the stories deal with family and marital relations, homes feature prominently in the action and as settings. Often characters are estranged or exiled, and their obsessions with having normal families and/or stable lives drive them to construct elaborate fantasies in which they are included, loved, and part of something enduring that is larger than themselves. The dissertation also includes a critical paper, “A Butterfly, a Cannonball, and a Sneeze: Notions of Chaos Theory in Cormac McCarthy’s All The Pretty Horses and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49.” In this essay, I argue that the novel All The Pretty Horses grapples with a sense of freedom that is rife with ambiguity and demonstrates McCarthy’s engagement with chaos theory.