Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Call of the Siren: Bod, Baútisos, Baîtai, and Related Names (Studies in Historical Geography II)

The Call of the Siren: Bod, Baútisos, Baîtai, and Related Names (Studies in Historical Geography II) Bettina Zeisler (Universität Tübingen) 1. Introduction eographical or ethnical names, like ethnical identities, are like slippery fishes: one can hardly catch them, even less, pin them G down for ever. The ‘Germans’, for example, are called so only by English speakers. The name may have belonged to a tribe in Bel- gium, but was then applied by the Romans to various tribes of North- ern Europe.1 As a tribal or linguistic label, ‘German (ic)’ also applies to the English or to the Dutch, the latter bearing in English the same des- ignation that the Germans claim for themselves: ‘deutsch’. This by the way, may have meant nothing but ‘being part of the people’.2 The French call them ‘Allemands’, just because one of the many Germanic – and in that case, German – tribes, the Allemannen, settled in their neighbourhood. The French, on the other hand, are called so, because a Germanic and, in that case again, German tribe, the ‘Franken’ (origi- nally meaning the ‘avid’, ‘audacious’, later the ‘free’ people) moved into France, and became the ruling elite.3 The situation is similar or even worse in other parts of the world. Personal names may become ethnic names, as in the case of the Tuyu- hun. 4 Names of neighbouring tribes might be projected onto their overlords, as in the case of the Ḥaža, who were conquered by the Tuyuhun, the latter then being called Ḥaža by the Tibetans. Ethnic names may become geographical names, but then, place names may travel along with ethnic groups. -

Ancient Rome and the Eurasian Trade Networks

Journal of Eurasian Studies 8 (2017) 3–9 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Eurasian Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/euras Beyond frontiers: Ancient Rome and the Eurasian trade networks Marco Galli Department of Ancient Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, P.le Aldo Moro 5, Rome 00185, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: During the second half of the 19th century, the Roman Empire was already considered one Received 23 September 2016 of the key players inside the Eurasian networks. This research focuses on four relevant points. Accepted 7 December 2016 From a historiographical perspective, the reconstruction of the trading routes represented Available online 16 December 2016 a central theme in the history of the relationship between the Roman Empire and the Far East. Imagining a plurality of itineraries and combinations of overland and sea routes, it is Keywords: possible to reconstruct a complex reality in which the Eurasian networks during the Early Roman Empire Roman Empire developed. As far as economics is concerned, new documentation demon- Silk Roads Roman & Eastern Trade strates the wide range and the extraordinary impact of the Eastern products on Roman markets. A final focus on the process of Chinese silk unravelling and reweaving provides an important clue on how complex and absolutely not mono-directional were the inter- actions and the exchanges in the Eurasian networks during the first centuries of the Roman Empire. Copyright Copyright © 2017, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Hanyang University. Production and hosting by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Maes Titianus, Ptolemy and the “Stone Tower” on the Great Silk Road

MAES TITIANUS, PTOLEMY AND THE “STONE TOWER” ON THE GREAT SILK ROAD Igor’ Vasil’evich P’iankov Novgorod State University he “Stone Tower” (Λίθινος πύργος) is mentioned then supplemented the Seleucid map with new ma- T as the most important landmark on the Great Silk terial contributed by Marinus of Tyre and by Ptolemy Road in the famous “Geographical Guide” of Clau- himself. Among the new sources was the itinerary of dius Ptolemy. Ptolemy knew about the “Stone Tow- Maes Titianus. er” from two sources: first of all, via his predecessor Such an interpretation belongs to the category of hy- Marinus of Tyre from the itinerary of Maes Titianus. potheses which are impossible to prove or disprove. This itinerary contained the only complete descrip- The various “rotations” are pure supposition with the tion from Classical Antiquity of the land route of the help of which one can explain anything one wishes. Great Silk Road from Roman Syria to the capital of But in general the method presupposed by this hy- China. Secondly, Ptolemy drew his information from pothesis — the creation of a global map by means of sailors, his contemporaries, when the land route had a diligent combination of many regional document already been connected through India with the mar- maps —is not characteristic for ancient science. Broad itime route. Both of these sources indicated that the generalizations in both ancient Greek geography and “Stone Tower” divided the Great Silk Road at its mid- ancient Greek historiography always were developed point. Ptolemy’s information about this is both in the on the basis of and within the framework of literary narrative part of his work and in his description of his tradition. -

Ipek Yolu'nun Iran Güzergâhi Ve Ipek Yolu Ticaretine Iran

Uluslararası Türkçe Edebiyat Kültür Eğitim Dergisi Sayı: 3/1 2014 s. 96-123, TÜRKİYE International Journal of Turkish Literature Culture Education Volume 3/1 2014 p. 96-123, TURKEY İPEK YOLU’NUN İRAN GÜZERGÂHI VE İPEK YOLU TİCARETİNE İRAN ENGELLEMESİ Mehmet TEZCAN Özet İpek Yolu’nun araştırılma tarihi, Doğu’da MÖ II. yy.’nin ikinci yarısında Çin elçisi Zhang Qian ile, Batı’da ise MS I. yy. başlarında Grek tüccarı Maes Titianus ile başlatılmaktadır. Antik dönemde ve Orta Çağ başlarında, Batı’dan Doğu’ya kara yoluyla Antakya bölgesinden başlayarak Kuzey Mezopotamya ve İran içerisinden geçmek zorunda olan İpek Yolu güzergâhı, daha sonra Batı ve Doğu Türkistan bölgelerinden geçmek suretiyle Çin başkentleri Chang’an ve Loyang’a kadar uzanmaktaydı. Fakat İran’da kurulan devletlerin, ipekten ve bu yoldan geçen ticaretten daha fazla kâr etme arzuları sebebiyle İran güzergâhı Parthlar ve Sasaniler Dönemi’nde genellikle kapalı kalmıştır. Roma Dönemi’nden beri Kızıl Deniz aracılığıyla Doğu ile yapılan deniz ticareti de 570 tarihlerinde Sasaniler tarafından engellenince, Bizans Devleti, Orta Asya’da yeni kurulan Türk Kağanlığı ile anlaşma yaparak bu güzergâhı Karadeniz üzerinden geçirmek zorunda kalmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: İpek Yolu, ipek, İran, Parthlar, Sasaniler, Bizans, Türk Kağanlığı. THE IRANIAN BRANCH OF THE SILKROAD AND THE PREVENTION OF THE SILK TRADE BY IRAN Abstract History of studies on the Silkroad begins with Zhang Qian, a famous Chinese ambassador in the East, in the second half of the 2nd century BC in the East, and with Maes Titianus, a Greek trader in the West in the early years of the 1st century AD. In the Antiquity and Early Middle Ages, the Silkroad began to its journey from Antiochia in the West through the territories of Northern Mesopotamia and Iran and then the Western and Eastern Turkestan in Central Asia and finished in Chang’an and Loyang, the two capitals of China in the East. -

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Departments of Archaeology and History (joint) By Paul Wilson Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. 1 Abstract: The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads The Kushans were a major historical power on the ancient Silk Roads, although their influence has been greatly overshadowed by that of China, Rome and Parthia. That the Kushans are so little known raises many questions about the empire they built and the role they played in the political and cultural dynamics of the period, particularly the emerging Silk Roads network. Despite building an empire to rival any in the ancient world, conventional accounts have often portrayed the Kushans as outsiders, and judged them merely in the context of neighbouring ‘superior’ powers. By examining the materials from a uniquely Kushan perspective, new light will be cast on this key Central Asian society, the empire they constructed and the impact they had across the region. Previous studies have tended to focus, often in isolation, on either the archaeological evidence available or the historical literary sources, whereas this thesis will combine understanding and assessments from both fields to produce a fuller, more deeply considered, profile. -

Empires of Ancient Eurasia Craig Benjamin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11496-8 — Empires of Ancient Eurasia Craig Benjamin Index More Information Index Achaemenid Persian Empire, 149 Aryan Language, 189 Adulis, 228 Ashoka, 154 Afanasevo,24 Assyrian Empire, 158 Afrasiab, 179 Atheas, 159 Age of Disunity, 241, 244, 261, 263, 264 Augustus, 120, 127, 129, 130 Aksu, 105 Augustus, 117, 131, 133, 138, 142, 144, Alai Valley, 139 146, 161, 162, 167, 170, 186, 194, 213, Alexander of Macedon, 151 225, 226, 227, 258, 278 Alexander Severus, 255, 256 Aurelius Victor, 258 Alexandria, 154 Avesta, 268 Alexandria on the Tigris, 229 Ammianus Marcellinus, 248, 272, 284 Bactra, 38, 75, 78, 84, 101, 108, 132, 137, Amu Darya, 37, 38, 68, 76, 98, 108, 139, 140 180, 183 Bactria, 75 Amyrgian Saka, 159 Bactrian Camel, 112 An Shigao, 157 Bai Yue, 232 Ancient Globalization, 12 Balikh River, 131 Andronovo,24 Ball, Warwick, 5 Angkor, 270 Ban Chao, 173, 182, 187 Angkor Thom, 270 Barbaricum, 219 Angkor Wat, 270 barracks-emperors, 259 Angra Mainyu, 267 Barygaza, 219 Annales group, 11 Basra, 229 Antigonids, 154 Battle of Cannae, 124 Antioch, 131, 133, 135, 166, 175, 284 Battle of Carrhae, 119, 161, 162 Antiochus IV, 230 Battle of Gaugamela, 153 Antiochus VII, 156 Battle of Hormozdgan, 250 Antonine Plague, 272 Battle of Naissus, 257 Antoninus, 164, 174, 272 Battle of Nihawand, 254 Anxi, 76 Battle of Philippi, 162 Apologos, 135, 229, 230, 231, Battle of Plataea, 152 Appian of Alexandria, 136, 284 Battle of the Milvian Bridge, 266 Arabian Peninsula, 226 Bay of Bengal, 206, 232 Ardashir, 198, 238, 245, 249, -

Orbem Terrarum Subicere Egyetem Ókortörténeti Tanszékének Vezetője

Grüll Tibor (1964) az MTA doktora, egyetemi tanár, a Pécsi Tudomány- Orbem terrarum subicere egyetem Ókortörténeti Tanszékének vezetője. Fő kutatási területe a Ró- mai Birodalom története, ezen belül Világbirodalmi törekvések és földrajzi gazdaságtörténeti, földrajzi és ökoló- giai kérdések, valamint a helléniszti- ismeretek az ókori Rómában kus és római kori judaizmus és a ko- rai kereszténység világa. Legutóbbi kötete: A Római Birodalom gazdasá- Grüll Tibor ga (Budapest, 2017). Legutóbbi írása az Ókorban: Igazság és hazugság a római törté- netíróknál és az epigráfiai emlékek- ben (2017/4). Nagy Sándor, a hódító és felfedező ár Nagy Sándornak is megvoltak a maga „világbíró” elődei a mezopotámiai és egyiptomi uralkodók között – elegendő itt Borzsák István kutatásai nyomán BSesóstris példájára hivatkoznunk1 –, a nyugati, és így a római hagyományban is ő volt és maradt a paradigmatikus világhódító, akinek tettei csak az istenekével ösz- szemérhetők, s így az aemulatio, azaz a versengés örökös tárgyai a vággyal (pothos) teli utódok előtt.2 Jóllehet Alexandros „Zeus gyermekének” vallotta magát, hódításai- ban mindvégig a Héraklésszel és Dionysosszal való versengés ösztönözte.3 Az ókori források egybehangzóan állítják, hogy hódításai során a Hyphasis (szanszkritül Vipa- sa, ma Beas) folyóig jutott el Kr. e. 326-ban, ahol serege fellázadt, és visszafordulásra kényszerítette. Ennek emlékére – birodalmának határjelzőiként – tizenkét hatalmas oltárt emelt a folyó bal partján a tizenkét olymposi istenségnek dedikálva azokat (Arr. Anab. V. 29, 1).4 De vajon meddig akart eljutni Alexandros? Ennek a kérdésnek a megválaszolásá- hoz Kr. e. 331-ig, Nagy Sándor Siwa oázisban tett látogatásáig kell visszamennünk (1. kép).5 Ókori forrásaink egybehangzóan állítják, hogy az orákulumnak feltett egyik kérdése úgy hangzott: elnyeri-e a világ feletti uralmat? Diodóros „az egész föld fe- letti uralom”-ról (tén hapasés gés archén, XVII. -

“The Silk Road”?

Did Richthofen Really Coin “the Silk Road”? Matthias Mertens here is little doubt that Ferdinand von the person who first conceived of a significant TRichthofen, the famous German geographer, word or thing has been crucial for the evolution of played an important role in conceptualizing and modern Western public consciousness” (2014: 417). popularizing the idea of a “silk road.” According to Because of this collective tendency, “intellectual historian Daniel C. Waugh, “almost any discussion innovators and technological inventors have been of the Silk Road today will begin with the obliga singled out and showered with praise” (417). tory reminder that the noted German geographer Richthofen is an excellent example of the individu [Ferdinand von Richthofen] had coined the term, alizing drive described by James and Stenger. As an even if few seem to know where he published it intellectual innovator, Richthofen certainly did and what he really meant” (2007: 1). But did much to consolidate the concept of “the silk road” Richthofen really invent the phrase “the Silk Road,” and introduce it to a broader, albeit still academic, either in its singular (die Seidenstrasse) or plural audience. But was Richthofen truly the sole inven (Seidenstrassen) usages? The German archaeolo tor of the term? gist and geographer Albert Herrmann certainly With the aid of electronic search engines, a ques thought so. In 1910, Herrmann boldly declared that tion like this is now much easier to answer. If “it was he [Richthofen] who introduced into litera Richthofen invented the term in 1877, as is often ture the apt name silk roads [Seidenstrassen]” asserted, then it should not appear in books or ar (Herrmann 1910: 7). -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

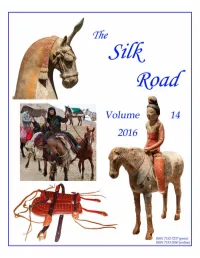

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Dynamics in the History of Religion

Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Dynamics in the History of Religion Editor-in-Chief Volkhard Krech Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany Advisory Board Jan Assmann – Christopher Beckwith – Rémi Brague José Casanova – Angelos Chaniotis – Peter Schäfer Peter Skilling – Guy Stroumsa – Boudewijn Walraven VOLUME 2 Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks Mobility and Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia By Jason Neelis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc-by-nc License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Detail of the Śibi Jātaka in a petroglyph from Shatial, northern Pakistan (from Ditte Bandini-König and Gérard Fussman, Die Felsbildstation Shatial. Materialien zur Archäologie der Nordgebiete Pakistans 2. Mainz: P. von Zabern, 1997, plate Vb). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Neelis, Jason Emmanuel. Early Buddhist transmission and trade networks : mobility and exchange within and beyond the northwestern borderlands of South Asia / By Jason Neelis. p. cm. — (Dynamics in the history of religion ; v. 2) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Buddhist geography—Asia. 2. Trade routes—Asia—History. 3. Buddhists—Travel—Asia. I. Title. II. Series. BQ270.N44 2010 294.3’7209021—dc22 2010028032 ISSN 1878-8106 ISBN 978 90 04 18159 5 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

The Role of Palmyrene Temples in Long- Distance Trade in the Roman Near East by John Berkeley Grout

The Role of Palmyrene Temples in Long- Distance Trade in the Roman Near East by John Berkeley Grout A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, University of London Summer, 2016 Supervisor: Prof. Richard Alston, Department of Classics D M PAUL R. A. D’ALBRET BERKELEY AVUS CARISSIMUS DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, John Berkeley Grout, hereby affirm that this thesis and the work presented herein is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly indicated. Signed, John Berkeley Grout ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the archaeology, epigraphy and historiography of Palmyrene temples and long- distance trade in early Roman Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and western Iraq. Forty-two temples are examined, both Palmyrene and comparanda, in both urban and rural settings. New models are proposed which characterise the roles which these temples are shown to have played in long-distance trade. These models include: ‘networking’ temples acting as foci for the network of trust upon which long-distance trade relied; ‘hosting’ temples acting as foci of trade itself, hosting fairs and exhibiting wealth from long-distance trade; and ‘supporting’ temples directly supporting trade via infrastructure such as waystations or caravanserais. New insight is thus provided into the role of temple institutions in the broader economy, in urban and rural life, and in the fabric of society as a whole. In the first part, fundamentals are established, terms defined and academic and historical background set, including the historiographical context of the thesis. -

Contacts Between Han China and the Roman Empire

www.chinaandrome.org/english/essays Contacts between Han China and the Roman Empire Sunny Y. Auyang In 330 BCE, Alexander led the Macedonian army into Central Asia to finish off the Persian Empire. In Bactria, now northern Afghanistan, he married his only queen, Roxanne. Yet he did not penetrate the Pamir, the knot of snowy mountains that now forms the western terminus of China. In Alexander’s time, China was in its Warring-states period, when seven large states battled each other among smaller contenders. Qin, the one that would defeat all rivals and create a unified China in 221 BCE, was the westernmost of the warring states. For more than five centuries, the Qin state sat at the gateway to a thousand-kilometer long natural corridor leading west, receiving all western traffic. Not surprisingly the western name “China” was derived from Qin. Figure 1. Eurasia geopolitics in the fourth century BEC, when Alexander's empire reached Central Asia. The Qin Dynasty that inaugurated imperial China resembled Alexander’s empire in its short life span. It was succeeded by the Han Dynasty, which lasted four centuries. Imperial China began with a cosmopolitan outlook. The Han dispatched its first western mission in 138 BCE, eagerly absorbed the foreign intelligence he brought back, and adopted a proactive policy toward what it called Xiyu, the Western Territory, today a part of China’s Xinjiang Province. A land of oasis scattered among deserts and mountains, the Western Territory stretched out like an arm, bridging the core of Han China with the lands of Central Asia.