Distinguishing the Rinceau Carvers.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter Suzanne C. Walsh A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Jaroslav Folda Dr. Eduardo Douglas Dr. Dorothy Verkerk Abstract Suzanne C. Walsh: The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter (Under the direction of Dr. Jaroslav Folda) The Saint Louis Psalter (Bibliothèque National MS Lat. 10525) is an unusual and intriguing manuscript. Created between 1250 and 1270, it is a prayer book designed for the private devotions of King Louis IX of France and features 78 illustrations of Old Testament scenes set in an ornate architectural setting. Surrounding these elements is a heavy, multicolored border that uses a repeating pattern of a leaf encircled by vines, called a rinceau. When compared to the complete corpus of mid-13th century art, the Saint Louis Psalter's rinceau design has its origin outside the manuscript tradition, from architectural decoration and metalwork and not other manuscripts. This research aims to enhance our understanding of Gothic art and the interrelationship between various media of art and the creation of the complete artistic experience in the High Gothic period. ii For my parents. iii Table of Contents List of Illustrations....................................................................................................v Chapter I. Introduction.................................................................................................1 -

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington Principal Investigators: Jennifer B. Leynes Kelly E. Wiles Prepared by: RGA, Inc. 259 Prospect Plains Road, Building D Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 Prepared for: Morris County Department of Planning and Public Works, Division of Planning and Preservation Date: October 15, 2015 BOROUGH OF MADISON MUNICIPAL OVERVIEW: THE BOROUGH OF MADISON “THE ROSE CITY” TOTAL SQUARE MILES: 4.2 POPULATION: 15,845 (2010 CENSUS) TOTAL SURVEYED HISTORIC RESOURCES: 136 SITES LOST SINCE 19861: 21 • 83 Pomeroy Road: demolished between 2002-2007 • 2 Garfield Avenue: demolished between 1987-1991 • Garfield Avenue: demolished c. 1987 • Madison Golf Club Clubhouse: demolished 2007 • George Wilder House: demolished 2001 • Barlow House: demolished between 1987-1991 • Bottle Hill Tavern: demolished 1991 • 13 Cross Street: demolished between 1987-1991 • 198 Kings Road: demolished between 1987-1991 • 92 Greenwood Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • Wisteria Lodge: demolished 1988 • 196 Greenwood Avenue: demolished between 2002-2007 • 194 Rosedale Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • C.A. Bruen House: demolished between 2002-2006 • 85 Green Avenue: demolished 2015 • 21, 23, 25 and 63 Ridgedale Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape/Bottle Hill Historic District: demolished c. 2013 • 21 and 23 Cook Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape: demolished between 1995-2002 RESOURCES DOCUMENTED BY HABS/HAER/HALS: • Bottle Hill Tavern (117 Main -

Lot Description LOW Estimate HIGH Estimate 2000 German Rococo Style Silvered Wall Mirror, of Oval Form with a Wide Repoussé F

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate German Rococo style silvered wall mirror, of oval form with a wide repoussé frame having 2000 'C' scroll cartouches, with floral accents and putti, 27"h x 20.5"w $ 300 - 500 Polychrome Murano style art glass vase, of tear drop form with a stick neck, bulbous body, and resting on a circular foot, executed in cobalt, red, orange, white, and yellow 2001 wtih pulled lines on the neck and large mille fleur designs on the body, the whole cased in clear glass, 16"h x 6.75"w $ 200 - 400 Bird's nest bubble bowl by Cristy Aloysi and Scott Graham, executed in aubergine glass 2002 with slate blue veining, of circular form, blown with a double wall and resting on a circular foot, signed Aloysi & Graham, 6"h x 12"dia $ 300 - 500 Monumental Murano centerpiece vase by Seguso Viro, executed in gold flecked clear 2003 glass, having an inverted bell form with a flared rim and twisting ribbed body, resting on a ribbed knop rising on a circular foot, signed Seguso Viro, 20"h x 11"w $ 600 - 900 2004 No Lot (lot of 2) Art glass group, consisting of a low bowl, having an orange rim surmounting the 2005 blue to green swirl decorated body 3"h x 11"w, together with a French art glass bowl, having a pulled design, 2.5"h x 6"w $ 300 - 500 Archimede Seguso (Italian, 1909-1999) art glass sculpture, depicting the head of a lady, 2006 gazing at a stylized geometric arch in blue, and rising on an oval glass base, edition 7 of 7, signed and numbered to underside, 7"h x 19"w $ 1,500 - 2,500 Rene Lalique "Tortues" amber glass vase, introduced 1926, having a globular form with a 2007 flared mouth, the surface covered with tortoises, underside with molded "R. -

Corinth, 1987: South of Temple E and East of the Theater

CORINTH, 1987: SOUTH OF TEMPLE E AND EAST OF THE THEATER (PLATES 33-44) ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens were conductedin 1987 at Ancient Corinth south of Temple E and east of the Theater (Fig. 1). In both areas work was a continuationof the activitiesof 1986.1 AREA OF THE DECUMANUS SOUTH OF TEMPLE E ROMAN LEVELS (Fig. 1; Pls. 33-37:a) The area that now lies excavated south of Temple E is, at a maximum, 25 m. north-south by 13.25 m. east-west. The earliest architecturalfeature exposed in this set of trenches is a paved east-west road, identified in the 1986 excavation report as the Roman decumanus south of Temple E (P1. 33). This year more of that street has been uncovered, with a length of 13.25 m. of paving now cleared, along with a sidewalk on either side. The street is badly damaged in two areas, the result of Late Roman activity conducted in I The Greek Government,especially the Greek ArchaeologicalService, has again in 1987 made it possible for the American School to continue its work at Corinth. Without the cooperationof I. Tzedakis, the Director of the Greek ArchaeologicalService, Mrs. P. Pachyianni, Ephor of Antiquities of the Argolid and Corinthia, and Mrs. Z. Aslamantzidou, epimeletria for the Corinthia, the 1987 season would have been impossible. Thanks are also due to the Director of the American School of Classical Studies, ProfessorS. G. Miller. The field staff of the regular excavationseason includedMisses A. A. Ajootian,G. L. Hoffman, and J. -

TROVE at ICFF 2014 Release FINAL

TROVE BRINGS STUNNING NEW SPRING COLLECTION TO ICFF New York, NY, May 17-20 Booth #2006 (May, 2014 – New York, NY) Returning to ICFF this year, Trove celebrates spring with an alluring new collection of images and patterns that once again push the dimension of wallpaper design in beautiful and unexpected ways. Jee Levin and Randall Buck, co- founders of Trove, are innovative multimedia designers who approach each new collection as artists to a blank canvas. Drawing influences from myriad media and experiences—from architecture, film and art history to travel and nature—this new collection exhibits the distinctive qualities of Trove designs: surprising scale, unconventional color palette, and a poetry and grace that transforms walls into works of art, inviting interpretation. At ICFF in the Javits Center (Booth #2006), Trove will present five arresting new designs: Allee, Rinceau, Grotte, Suichuka, and Macondo along with Trace, a recently released design that makes its ICFF debut this year. All of the patterns are available in 6 colorways and in Trove’s signature scale, which repeats at 12-foot high and 6-foot wide and can be customized to height. Allee Allee presents an expansive dreamscape inspired by Alain Resnais’ 1961 film, “Last Year at Marienbad.” Set in an unspecified formal garden, the film plays with spatial and temporal shifts in scenes to create an ambiguous narrative. The designers translate the cinematic repetition to photographic repetition, composing a landscape organized around a central pathway thereby inviting the passerby to wander into this mise en scene. Rinceau French for foliage, “rinceau” describes a style of filigree that is characterized by leafy stems, florid swirls and sinuous natural elements. -

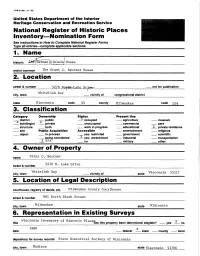

6. Representation in Existing Surveys______Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Places

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department off the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name r^L._ | historic J^£^erman\Uihleiii! House and/or common The Grant C. Beutner House 2. Location street & number 5270 North-Lake Drive- not for publication Whitefish Bay city, town vicinity of congressional district state Wisconsin code 55 county Milwaukee code Q79 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _ district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered •"•Y yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X N/A no military other: 4. Owner off Property name Grant C, Beutner street & number 5270 N. Lake Drive Whitefish Bay city, town vicinity of state Wisconsin 53217 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Milwaukee County Courthouse street & number 901 North Ninth Street Milwaukee city, town state Wisconsin 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Places ... _ . 4 . , .. , _ x title Has this property been determined elegible? __ yes __ no 1980 X date federal state county local depository for survey records State Historical Society of Wisconsin city, town Madison state Wisconsin 53706 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered original site X good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance Dramatically sited on a bluff overlooking Lake Michigan in the tillage of Whitefish Bay, the Herman Uihlein house is an imposing limestone residence, characterized by classical detailing, ornate craftsmanship, and eclectic interior design. -

Catalog Georgia Hardwoods Who We Are Left

Georgia Hardwoods Inc www.gahwd.com Designer Catalog Established in 1988, Georgia Hardwoods has over 20 years of excellence as a leading distributor of quality plywood, lumber and hardware products in the entire southeast. We have a strong partnership with some of the most well known and respected suppliers in the industry which enables us to provide you with the highest quality products and the best service available. In 1997, Georgia Hardwoods took a giant leap into manufacturing by producing Who We Are high quality raised panel doors, drawer fronts and MDF thermofoil wrapped doors. Increased demand prompted us to included the manufacturing of hard- wood mouldings to complement our line of plywood and doors. In 2001, custom made dovetail drawerboxes were also added to our product line to give our customers a more complete ordering experience. Since then, Georgia Hardwoods has invested millions of dollars in state of the art machinery and facility upgrades which enables us to be more efficient while providing the highest quality products and services. Our product line has grown to include cabinetry accents such as arch mouldings and a complete line of cabi- net storage solutions. A fully operational spray line system was installed in late 2006 and allows us to apply stain or paint finishes to most of the products we sell. In October of 2007, we began constructing high end kitchen range hoods in solid wood as well as stocking stainless steel alternatives to suit any style. Georgia Hardwoods has a fleet of trucks from small city vans to full sized tractor trailers as well as a daily common carrier service that enables us to service the entire southeast region and beyond. -

Design Characteristics of Culturally-Themed Luxury Hotel Lobbies in Las Vegas: Perceptual, Sensorial, and Emotional Impacts of Fantasy Environments

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Design characteristics of culturally-themed luxury hotel lobbies in Las Vegas: Perceptual, sensorial, and emotional impacts of fantasy environments Qingrou Lin Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lin, Qingrou, "Design characteristics of culturally-themed luxury hotel lobbies in Las Vegas: Perceptual, sensorial, and emotional impacts of fantasy environments" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18025. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18025 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Design characteristics of culturally-themed luxury hotel lobbies in Las Vegas: Perceptual, sensorial, and emotional impacts of fantasy environments by Qingrou Lin A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Interior Design Program of Study Committee: Diane Al Shihabi, Major Professor Jae Hwa Lee Sunghyun Ryoo Kang The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Qingrou Lin, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... -

Hanau Gold Snuff Box with Pietra Dura Medallion. Mid -19Th Century Large Rectangular Snuff Box in Several Shades of Gold with Enamel and Hard Stone

Hanau Gold Snuff Box with Pietra Dura Medallion. Mid -19th Century Large rectangular snuff box in several shades of gold with enamel and hard stone. The hinged the lid inset with a Florentine pietra dura panel inlaid with jasmine and forget-me-not on a black Belgian marble ground. The pink gold floral motif that surrounds the medallion is itself framed with a yellow gold frieze of stylized laurels. The sides of the box are decorated with oblong panels with friezes of rinceaux on matte gold backgrounds. Each panel is outlined in two royal blue enamel stripes. The rounded corners feature vases accented with blue enamel. The base of the box is entirely covered with a delicate relief. The main panel portrays a cornucopia framed with rinceau on a matte gold base and embellished with a rinceau frame accented with royal blue enamel. The pietra dura technique used on this box was developed in Florence, Italy under the influence of the Grand Dukes of Tuscany during the 16th century. Semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, agate, and jasper were cut, then inlaid in black marble, and then polished. This technique has endured in the same was as mosaic has stood the test of time. Aristocrats, during their “Grand Tour” of Europe, would not miss the opportunity to bring back souvenirs like this one, with its inlay on the lid of an exceptional snuff box. The box is marked with gold marks from Hanau, Germany. Hanau was an important center of production of snuff boxes and other hard stone objects beginning in the 18th century. -

The Golden Age of Clock-Making in the Jerez “Palace of Time”

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CLOCK-MAKING IN THE JEREZ “PALACE OF TIME” Museum of Historical Clocks A museum where the greatest master clockmakers are represented according to country, time period, and style The collection of 287 clocks spans the XVII to XIX centuries, considered the most productive and diverse period for French and English clockmaking techniques. It also includes models from other countries, including Austria, Switzerland, and Italy. Of particular note is a mantel clock whose Italian case is the oldest timepiece in the Museum (from around 1670) which later housed an English clock of superb quality and precision made by Charles Frodsham, clockmaker to Queen Victoria (XIX C.). It is on exhibition in the Arturo Paz Room. Also on display are the famous Geneva pocket watches and the exquisitely crafted Austrian “carriage” clock, with these models representing only a sampling of the quality and singularity of this unique collection. LAMP POST CLOCK (6044) Losada Hall English Clock 1867 Public 4-sided clock constructed in gilt bronze. It was housed on a grey iron lamp post in the Arenal square of Jerez, where the post can still be found today. It was commissioned by the Jerez City Council and installed in 1867. Its four glass dials were lit from the inside with gas lamps, creating the appearance of a streetlamp. José Rodríguez Losada, in his Regent Street workshop, made clocks such as the one found in the Málaga cathedral, the Gobernación clock in Madrid (in Puerta del Sol square), and the clock that was located on the Charing Cross bridge in London, which was very similar to the street lamp clock in Jerez. -

Words of the Champions Is the Official Study Resource of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, So You’Ve Found the Perfect Place to Start

2020 GREETINGS, CHAMPIONS! About this Study Guide Do you dream of winning a school spelling bee, or even attending the Scripps National Spelling Bee? Words of the Champions is the official study resource of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, so you’ve found the perfect place to start. Prepare for a 2019 or 2020 classroom, grade-level, school, district, county, regional or state spelling bee with this list of 4,000 words. All words in this book have been selected by the Scripps National Spelling Bee from our official dictionary,Merriam- Webster Unabridged (http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com). Words of the Champions is divided into three difficulty levels, ranked One Bee (800 words), Two Bee (2,100 words) and Three Bee (1,200 words). These are great words to challenge you, whether you’re just getting started in spelling bees or of if you’ve already participated in several. At the beginning of each level, you’ll find theSchool Spelling Bee Study List words. For any classroom, grade-level or school spelling bee, study the 125-word One Bee School Spelling Bee Study List, the 225-word Two Bee School Spelling Bee Study List and the 100-word Three Bee School Spelling Bee Study List: a total of 450 words. Following the School Spelling Bee Study List in each level, you’ll find pages marked “Words of the Champions.” Are you a school spelling bee champion or a speller advancing to compete beyond the school level? Study these pages to make sure you’re prepared to do your best when these words are asked in the early rounds of competition. -

Depliant Guide

History Visit The early Renaissance Information History Visit The early Renaissance Information History Visit The early Renaissance Information L L L English The early Renaissance in the Périgord Glossary Puyguilhem Persisting Gothic influences Bonnivet : castle belonging to Guillaume Gouffier, a favourite of François I. Built in the Château A first phase of building ran from 1510 to 1517, . Poitou between 1516 and 1525 but no longer 5 1 0 2 during which the round tower topped with r stands today. e An early Renaissance creation i v n a j machicolations was built. The windows are , * Hercules : the Roman name of the Greek hero a p i t S aligned at irregular intervals along the façade Heracles, embodying strength. He was n o i Construction s s of the buildings. e compelled to complete twelve labours to atone r p m i The spiral staircase is in an out-built polygonal . for the murder of his wife and children; the first e * l Mondot de La Marthonie, President of the z z u tower. These volumes still hark back to the P of these was to strangle the Nemean lion. n I Guyenne parliament in Bordeaux, bought the n * o i medieval tradition, and have low-relief rinceau Out-built : built up against another building. t c title of Puyguilhem at some stage before 1510. u d a decorations and letter friezes, the meaning of Machicolation : a stone gallery overhanging a wall r t He was a nobleman from the Perigord and legal . r e i which is obscure. There are also other patterns t enabling missiles to be dropped vertically.