The Golden Age of Clock-Making in the Jerez “Palace of Time”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials& Tools

Photocopy at 100% Note to professional copying services. You may make up to ten copies of these patterns for the personal use of the buyer of this magazine. TIP ZERO CLEARANCE INSERT Use a piece of cereal box or shirt cardboard to make a zero clearance insert. Drill a small blade-entry hole in the cardboard, and tape it to your saw table with some masking tape. The zero clearance insert helps support fragile areas and reduces the risk of breaking those parts. © 2007 Fox Chapel Publishing Co., Inc. Sue Mey lives in Pretoria, South Scroll Saw Woodworking & Crafts Africa. To see more of her work, Designer: Sue Mey visit www.geocities.com/meydenhart. Materials & Tools Materials: Tools: • 1" x 9" x 9" light colored hardwood • Wood stain – walnut (optional) • 3 and #9 reverse-tooth blades • Punch and mallet of choice (backing) • Deep-penetrating furniture wax or blades of choice • Sharp pencil • 1⁄8" x 8" x 8" Baltic birch plywood or liquid or Danish oil • Drill press with 1⁄16"-, 1⁄8"- and 5⁄16"- • Clamps, assorted sizes hardwood of choice (overlay) • Lint-free cloth diameter bits (size of the larger • Assorted paint brushes of • Masking tape • Wood glue bit may vary to match the shaft choice to apply the fi nish diameter of quartz movement) • Spray adhesive • Clear spray varnish • Disc sander and palm sander • Thin, double-sided tape (optional) • Saw-tooth hanger • Router with round-over bit • Sandpaper – assorted grits • Quartz movement and hands Free Pattern Download of FRETWORK OVERLAY CLOCK at www.ScrollSawer.com. 76 Scroll Saw Woodworking & Crafts ■ FALL 2007 FFretworkretwork OOverlayverlay CClock.inddlock.indd 7766 66/13/07/13/07 33:36:53:36:53 PPMM. -

Fretwork Program Detailed Instructions

Fretwork Program Detailed Instructions Fretwork is an art form whereby the artist produces a piece by cutting numerous holes (or frets) in a medium in order to produce a picture or design. In woodworking, that medium is normally wood, but other types of media can be used as well. Equipment The best tool for fretwork is a good-quality scroll saw, one that produces little vibration, and has more vertical motion of the saw blade. This is especially important for delicate pieces, as excessive vibration or blade friction on the wood can cause fragile pieces to break. Since fretwork involves threading a blade through a small hole to cut the frets, a saw that makes this process easier would be ideal. Excaliber and RBI are excellent choices, and I have had good luck with the DeWalt 780 I’ve owned for about 15 years, in spite of its limitations. Supplies Good quality blades are essential to good fretwork results. I have used Olsen blades in the past, which are probably marginal at best. I really like the Flying Dutchman blades, in particular the #1 Ultra Reverse. The blade is quite thin (one of the thinnest in their line), but I have no problems using it to cut material up to 1” thick. The reverse teeth on the bottom of the blade help to minimize “fuzzies” that you’ll get on the bottom of the piece as you’re cutting. For safety, of course safety glasses are a must, and some kind of dust mask for respiratory protection. Other things you’ll need (aside of the wood of choice and backer material) • A photocopier, or access to one (for producing patterns) • Spray adhesive • Paste wax • Mineral spirits • Sandpaper • Jointer and planer (if you’ll be preparing your own stock from rough cut) • Random orbit sander or drum sander (also for stock prep) • Drill press or hand drill • Small drill bits • Finishes Wood to use For fretwork in wood, the best results can be obtained by using close-grained hardwood, such as maple or German beech. -

The Art of Fretwork

FOSTERING A NEW AND COMPETITIVE APPROACH TO CRAFTS AND SEMI-INDUSTRIAL HIGH ADDED-VALUE SECTORS The Art of Fretwork Co-funded by the ESPAŇA Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union THE ART OF FRETWORK TOOLS AND MATERIALS .............................................................................................................. 3 CHARACTERISTICS ......................................................................................................................... 5 TECHNICS ............................................................................................................................................ 7 DESIGN AND PREPARATION ..................................................................................................... 10 CONTENTS TRANSFERENCE .............................................................................................................................. 11 FRETWORK ........................................................................................................................................ 11 CLEANING ........................................................................................................................................ 12 GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter Suzanne C. Walsh A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Jaroslav Folda Dr. Eduardo Douglas Dr. Dorothy Verkerk Abstract Suzanne C. Walsh: The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter (Under the direction of Dr. Jaroslav Folda) The Saint Louis Psalter (Bibliothèque National MS Lat. 10525) is an unusual and intriguing manuscript. Created between 1250 and 1270, it is a prayer book designed for the private devotions of King Louis IX of France and features 78 illustrations of Old Testament scenes set in an ornate architectural setting. Surrounding these elements is a heavy, multicolored border that uses a repeating pattern of a leaf encircled by vines, called a rinceau. When compared to the complete corpus of mid-13th century art, the Saint Louis Psalter's rinceau design has its origin outside the manuscript tradition, from architectural decoration and metalwork and not other manuscripts. This research aims to enhance our understanding of Gothic art and the interrelationship between various media of art and the creation of the complete artistic experience in the High Gothic period. ii For my parents. iii Table of Contents List of Illustrations....................................................................................................v Chapter I. Introduction.................................................................................................1 -

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington Principal Investigators: Jennifer B. Leynes Kelly E. Wiles Prepared by: RGA, Inc. 259 Prospect Plains Road, Building D Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 Prepared for: Morris County Department of Planning and Public Works, Division of Planning and Preservation Date: October 15, 2015 BOROUGH OF MADISON MUNICIPAL OVERVIEW: THE BOROUGH OF MADISON “THE ROSE CITY” TOTAL SQUARE MILES: 4.2 POPULATION: 15,845 (2010 CENSUS) TOTAL SURVEYED HISTORIC RESOURCES: 136 SITES LOST SINCE 19861: 21 • 83 Pomeroy Road: demolished between 2002-2007 • 2 Garfield Avenue: demolished between 1987-1991 • Garfield Avenue: demolished c. 1987 • Madison Golf Club Clubhouse: demolished 2007 • George Wilder House: demolished 2001 • Barlow House: demolished between 1987-1991 • Bottle Hill Tavern: demolished 1991 • 13 Cross Street: demolished between 1987-1991 • 198 Kings Road: demolished between 1987-1991 • 92 Greenwood Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • Wisteria Lodge: demolished 1988 • 196 Greenwood Avenue: demolished between 2002-2007 • 194 Rosedale Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • C.A. Bruen House: demolished between 2002-2006 • 85 Green Avenue: demolished 2015 • 21, 23, 25 and 63 Ridgedale Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape/Bottle Hill Historic District: demolished c. 2013 • 21 and 23 Cook Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape: demolished between 1995-2002 RESOURCES DOCUMENTED BY HABS/HAER/HALS: • Bottle Hill Tavern (117 Main -

Lot Description LOW Estimate HIGH Estimate 2000 German Rococo Style Silvered Wall Mirror, of Oval Form with a Wide Repoussé F

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate German Rococo style silvered wall mirror, of oval form with a wide repoussé frame having 2000 'C' scroll cartouches, with floral accents and putti, 27"h x 20.5"w $ 300 - 500 Polychrome Murano style art glass vase, of tear drop form with a stick neck, bulbous body, and resting on a circular foot, executed in cobalt, red, orange, white, and yellow 2001 wtih pulled lines on the neck and large mille fleur designs on the body, the whole cased in clear glass, 16"h x 6.75"w $ 200 - 400 Bird's nest bubble bowl by Cristy Aloysi and Scott Graham, executed in aubergine glass 2002 with slate blue veining, of circular form, blown with a double wall and resting on a circular foot, signed Aloysi & Graham, 6"h x 12"dia $ 300 - 500 Monumental Murano centerpiece vase by Seguso Viro, executed in gold flecked clear 2003 glass, having an inverted bell form with a flared rim and twisting ribbed body, resting on a ribbed knop rising on a circular foot, signed Seguso Viro, 20"h x 11"w $ 600 - 900 2004 No Lot (lot of 2) Art glass group, consisting of a low bowl, having an orange rim surmounting the 2005 blue to green swirl decorated body 3"h x 11"w, together with a French art glass bowl, having a pulled design, 2.5"h x 6"w $ 300 - 500 Archimede Seguso (Italian, 1909-1999) art glass sculpture, depicting the head of a lady, 2006 gazing at a stylized geometric arch in blue, and rising on an oval glass base, edition 7 of 7, signed and numbered to underside, 7"h x 19"w $ 1,500 - 2,500 Rene Lalique "Tortues" amber glass vase, introduced 1926, having a globular form with a 2007 flared mouth, the surface covered with tortoises, underside with molded "R. -

Corinth, 1987: South of Temple E and East of the Theater

CORINTH, 1987: SOUTH OF TEMPLE E AND EAST OF THE THEATER (PLATES 33-44) ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens were conductedin 1987 at Ancient Corinth south of Temple E and east of the Theater (Fig. 1). In both areas work was a continuationof the activitiesof 1986.1 AREA OF THE DECUMANUS SOUTH OF TEMPLE E ROMAN LEVELS (Fig. 1; Pls. 33-37:a) The area that now lies excavated south of Temple E is, at a maximum, 25 m. north-south by 13.25 m. east-west. The earliest architecturalfeature exposed in this set of trenches is a paved east-west road, identified in the 1986 excavation report as the Roman decumanus south of Temple E (P1. 33). This year more of that street has been uncovered, with a length of 13.25 m. of paving now cleared, along with a sidewalk on either side. The street is badly damaged in two areas, the result of Late Roman activity conducted in I The Greek Government,especially the Greek ArchaeologicalService, has again in 1987 made it possible for the American School to continue its work at Corinth. Without the cooperationof I. Tzedakis, the Director of the Greek ArchaeologicalService, Mrs. P. Pachyianni, Ephor of Antiquities of the Argolid and Corinthia, and Mrs. Z. Aslamantzidou, epimeletria for the Corinthia, the 1987 season would have been impossible. Thanks are also due to the Director of the American School of Classical Studies, ProfessorS. G. Miller. The field staff of the regular excavationseason includedMisses A. A. Ajootian,G. L. Hoffman, and J. -

2019 Calendar Please Read the Entire Brochure Before Entering

2019 San Diego County Fair ● May 31 - July 4 ● Del Mar, California 38th Annual Design In Wood Competition - An International Exhibition of Fine Woodworking Ed Gladney, Coordinator Presented in association with the San Diego Fine Woodworkers Association 2019 CALENDAR PLEASE READ THE ENTIRE BROCHURE BEFORE ENTERING Registration is only accepted online. Visit www.sdfair.com/entry to enter and pay the processing fees. Processing fees are non-refundable. Entry Registration Deadline: Friday, April 26, 2019. All registrations must be submitted online by 11:59pm (Pacific Daylight Time). Entry Office extended hours to 7:00pm on April 26, 2019. Late Entries Will Not Be accepted. Notification of Accepted Project(s): Notification of accepted work will be emailed by Wednesday, May 8, 2019 Delivery of Entries: Tuesday, May 21, 2019, Noon - 8:00pm (Shipped entries must arrive between May 13 – May 20) Awards Ceremony: Thursday, May 30, 2019, 7:00pm - 9:00pm Judging Results: Will be posted by Saturday, June 1 Entry Pick Up: Saturday, July 6, 2019, Noon - 8:00pm Questions? Call the Entry Office at (858) 792-4207 or email [email protected] Monday through Friday from 10:00am to 4:00pm Digital Image Upload Support: Need assistance with photographing your wood project? Make an appointment and bring your project to be photographed at the San Diego County Fair Entry Office. A staff member will take a photo of your project and assist you with the online entry process. 2019 Design In Wood at the San Diego County Fair COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS: 1. The Local and State Rules apply to this department, available at sdfair.com/entry. -

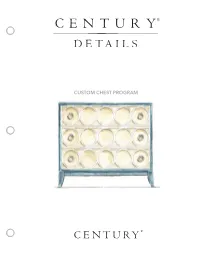

CUSTOM CHEST PROGRAM Yours for the Making

CUSTOM CHEST PROGRAM Yours for the Making. Custom Chest Program. With our versatile Chest program, you choose your Case, Drawer/Door front, Base, add your choice of Hardware, select its finish and its placement, then select your Stain or Paint finish. Style that suits your space—Yours for the Making. 1 SELECT YOUR CASE: Choose from eight style options. *Case heights combine with Base heights to create overall heights. CR9-221 CR9-222 Small Single Drawer Small Three Drawer Nightstand Nightstand 24 W 18.5 D 21.25 H 24 W 18.5 D 21.25 H CR9-225 CR9-226 Large Single Drawer Large Three Drawer Nightstand Nightstand 36 W 18.5 D 23.25 H 36 W 18.5 D 23.25 H CR9-702 CR9-703 Three Drawer Chest Two Door Chest 40 W 20.5 D 29.25 H 40 W 20.5 D 29.25 H CR9-201 CR9-202 Six Drawer Chest Four Door Chest 72 W 20.5 D 29.25 H 72 W 20.5 D 29.25 H 1 2 SELECT YOUR DRAWER/DOOR FRONT: Choose from five Drawer styles and five Door style options. DRAWERS Plain Drawer Bead Edge Drawer Picture Frame Drawer (PL) (BD) (PT) Fretwork Overlay Circle Overlay Drawer (FW) Drawer (CR) (Upcharge) (Upcharge) DOORS Plain Door Bead Edge Door Picture Frame Door (PL) (BD) (PT) Fretwork Overlay Circle Overlay Door (FW) Door (CR) (Upcharge) (Upcharge) 2 3 SELECT YOUR BASE: Choose from eight style options. *Base heights combine with Case heights to create overall heights. Metal Leg Brass Base (MB) Metal Leg Silver Base (MS) 6” H 6” H Tapered Leg Base (TP) Saber Leg Base (SB) 6.75” H 6.75” H Bracket Base (BK) Chow Base (CH) 6.75” H 6.75” H Turned Foot Base (TR) Plinth Base (PH) 6.75” H 4” H 3 4 SELECT YOUR HARDWARE and HARDWARE FINISH: Choose from eight style options. -

TROVE at ICFF 2014 Release FINAL

TROVE BRINGS STUNNING NEW SPRING COLLECTION TO ICFF New York, NY, May 17-20 Booth #2006 (May, 2014 – New York, NY) Returning to ICFF this year, Trove celebrates spring with an alluring new collection of images and patterns that once again push the dimension of wallpaper design in beautiful and unexpected ways. Jee Levin and Randall Buck, co- founders of Trove, are innovative multimedia designers who approach each new collection as artists to a blank canvas. Drawing influences from myriad media and experiences—from architecture, film and art history to travel and nature—this new collection exhibits the distinctive qualities of Trove designs: surprising scale, unconventional color palette, and a poetry and grace that transforms walls into works of art, inviting interpretation. At ICFF in the Javits Center (Booth #2006), Trove will present five arresting new designs: Allee, Rinceau, Grotte, Suichuka, and Macondo along with Trace, a recently released design that makes its ICFF debut this year. All of the patterns are available in 6 colorways and in Trove’s signature scale, which repeats at 12-foot high and 6-foot wide and can be customized to height. Allee Allee presents an expansive dreamscape inspired by Alain Resnais’ 1961 film, “Last Year at Marienbad.” Set in an unspecified formal garden, the film plays with spatial and temporal shifts in scenes to create an ambiguous narrative. The designers translate the cinematic repetition to photographic repetition, composing a landscape organized around a central pathway thereby inviting the passerby to wander into this mise en scene. Rinceau French for foliage, “rinceau” describes a style of filigree that is characterized by leafy stems, florid swirls and sinuous natural elements. -

Annual Report 2000

2000 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 2000 ylMMwa/ Copyright © 2001 Board of Trustees, Cover: Rotunda of the West Building. Photograph Details illustrated at section openings: by Robert Shelley National Gallery of Art, Washington. p. 5: Attributed to Jacques Androet Ducerceau I, All rights reserved. The 'Palais Tutelle' near Bordeaux, unknown date, pen Title Page: Charles Sheeler, Classic Landscape, 1931, and brown ink with brown wash, Ailsa Mellon oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.9 cm, Collection of Mr. and Bruce Fund, 1971.46.1 This publication was produced by the Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth, 2000.39.2 p. 7: Thomas Cole, Temple of Juno, Argrigentum, 1842, Editors Office, National Gallery of Art Photographic credits: Works in the collection of the graphite and white chalk on gray paper, John Davis Editor-in-Chief, Judy Metro National Gallery of Art have been photographed by Hatch Collection, Avalon Fund, 1981.4.3 Production Manager, Chris Vogel the department of photography and digital imaging. p. 9: Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of Saint Peter's Managing Editor, Tarn Curry Bryfogle Other photographs are by Robert Shelley (pages 12, Rome, c. 1754, oil on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce 18, 22-23, 26, 70, 86, and 96). Fund, 1968.13.2 Editorial Assistant, Mariah Shay p. 13: Thomas Malton, Milsom Street in Bath, 1784, pen and gray and black ink with gray wash and Designed by Susan Lehmann, watercolor over graphite, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Washington, DC 1992.96.1 Printed by Schneidereith and Sons, p. 17: Christoffel Jegher after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Baltimore, Maryland The Garden of Love, c. -

How to Identify Old Chinese Porcelain

mmmKimmmmmmKmi^:^ lOW-TO-IDENTIFY OLD -CHINESE - PORCELAIN - j?s> -ii-?.aaig3)g'ggg5y.jgafE>j*iAjeE5egasgsKgy3Si CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THE WASON CHINESE COLLECTION DATE DUE 1*-^'" """"^*^ NK 4565!h69" "-ibrary 3 1924 023 569 514 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023569514 'a4^(A<-^^ %//3 HOW TO IDENTIFY OLD CHINESE PORCELAIN PLATE r WHITE PORCELAIN "BLANC-DE-CHINE" PAIR OF BOWLS of pierced fret-work divided by five circular panels or medallions of raised figures in relief, supposed 10 represent the Pa-Sien or eight Immortals and the God of Longevity. Height, if in. Diameter, sfin. SEAL in the form of a cube surmounted by the figure of a lion Height, i^in. INCENSE BURNER, eight sided and ornamented by moulding in relief with eight feet and four handles. The sides have three bands enclosing scrolls in ancient bronze designs. At each angle of the cover is a knob; it is ornamented with iris and prunus, and by pierced spaces. The stand has eight feet and a knob at each angle ; in the centre is a flower surrounded by detached impressed scrolls, round the outside are similar panels to those on the bowl. Height, 4|in. Diameter of stand, 6f in. THE FIGURE OF A CRAB on a lotus leaf, the stem of which terminales in a flower. Length, 6| in. From Sir PV. fraiik^s Collection at the BritisJi Museum. S3 HOW TO IDENTIFY OLD CHINESE PORCELAIN BY MRS.