Two Early Biographies, Bernard, Maillefer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

179-San Francesco Di Paola Ai Monti.Pages

(179/16) San Francesco di Paola ai Monti ! San Francesco da Paola ai Monti is a 17th century titular church in Rome. It is dedicated to St Francis of Paola (the 15th century founder of the Minim Friars, whose friars serve this church and whose Generalate is attached to it), and is located in the Monti rione , perched on the raised corner above the Via Cavour. (1) History It was built 1645-50 with funds given by Princess Olimpia Aldobrandini Pamphili, who (like St Francis) had roots in Calabria. It was designed by Orazio Torriano, then Giovanni Pietro Morandi, given to the Minim Friars, and became the national church of the Calabrians. The late Baroque high altar was made by Giovanni Antonio de Rossi c. 1655 (who is also credited with the church's wooden tabernacle, set into a sculptured entrance of a military pavilion). No new bell tower was built for the church - instead the 12th century Torre dei Margani was used, preserving its medieval coat-of-arms on the tower has been preserved. (1) (4) However, the church as a whole was not consecrated until 10 July 1728, by Pope Benedict XIII. The lower part of the façade was refinished in plaster in the 18th century, and the whole church was then restored about a century later by Pope Leo XII. The church is now often closed, but you may ask to be admitted at the monastery. (1) (179/16) It is the conventual church of the Generalate of the Order of Minims next door, and is served by priests from that order. -

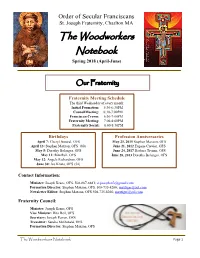

The Woodworkers Notebook Spring 2018 (April-June)

Order of Secular Franciscans St. Joseph Fraternity, Charlton MA The Woodworkers Notebook Spring 2018 (April-June) Our Fraternity Fraternity Meeting Schedule The third Wednesday of every month: Initial Formation: 5:30-6:30PM CouncilMeeting: 6:30-7:00PM Franciscan Crown: 6:30-7:00PM Fraternity Meeting: 7:00-8:00PM Fraternity Social: 8:00-8:30PM Birthdays Profession Anniversaries April 7: Cheryl Amaral, OFS May 23, 2015 Stephen Maxson, OFS April 13: Stephen Maxson, OFS (80) June 21, 2012 Eugene Crevier, OFS May 5: Dorothy Belanger, OFS June 24, 2017 Barbara Tivnan, OFS May 11: Rita Reil, OFS June 28, 2013 Dorothy Belanger, OFS May 12: Angels Richardson, OFS June 30: Joe Krans, OFS (54) Contact Information: Minister: Joseph Krans, OFS. 508-867-8881; [email protected] Formation Director: Stephen Maxson, OFS. 508-735-8266; [email protected] Newsletter Editor: Stephen Maxson, OFS 508-735-8266; [email protected] Fraternity Council: Minister: Joseph Krans, OFS Vice Minister: Rita Reil, OFS Secretary: Joseph Perron, OFS Treasurer: Sandra McDonald, OFS Formation Director: Stephen Maxson, OFS The Woodworkers Notebook Page 1 Upcoming Events Calendar APRIL: April 14: Regional Meeting. 9a to 3p. St Pius XII in Middletown CT. Carpool at 730a April 18: Fraternity Meeting. April 25: Franciscan Film Festival. From 6 to 8p. At the Cornerstone, St. Joseph’s Parish. John Paul II (2014) April 28: Regional Formation, 9a to 30. St Pius XII in Middletown CT. Car pool at 730a MAY: May 16: Fraternity Meeting. May 23: Franciscan Film Festival:. From 6 to 8p. At the Cornerstone, St. Joseph’s Parish. -

The Holy See

The Holy See SPEECH OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE PARTICIPANTS IN THE GENERAL CHAPTER OF THE ORDER OF MINIMS Monday, 3 July 2000 Dear Brothers of the Order of Minims! 1. I affectionately welcome you and am grateful for the visit you wanted to pay me at the beginnning of your General Chapter. I cordially greet Fr Giuseppe Fiorini Morosini, your Superior General, the Chapter fathers and the delegations of nuns and tertiaries who will be taking part in the first part of this important meeting, as well as the religious and lay people who form the three orders of the religious family founded by St Francis of Paola. I thank the Lord with all of you for the good accomplished in your long and praiseworthy history of service to the Gospel. My thoughts turn in particular to those difficult times for the Church when St Francis of Paola was engaged in carrying out a reform which drew to a new way of perfection all who were "moved by the desire for greater penance and love of the Lenten life" (IV Rule, chap. 2). 2. Inspired by apostolic goals, he founded the Order of Minims, a clerical religious institute with solemn vows, planted like "a good tree in the field of the Church militant" (Alexander VI) to produce worthy fruits of penance in the footsteps of Christ, who "emptied himself, taking the form of a servant" (Phil 2: 7). Following the founder's example, your religious family "intends to bear a special daily witness to Gospel penance by a Lenten life, that is, by total conversion to God, deep participation in the expiation of Christ and a call to the Gospel values of detachment from the world, the primacy of the spirit over matter and the urgent need for penance, which entails the practice of charity, love of prayer and physical ascesis" (Constitutions, art. -

St Francis of Paola Naples Who Was King at the Time

Lives of Saints 1416-1507 Feast day: 2nd April I loved contemplative solitude and wished only to be "the least in the household of God". But, the Church called me to active service in the world and I did my very best to fulfill my vocation. I accompanied my parents on a pilgrimage to Rome and Assisi and went to live as a contemplative hermit in a remote cave on the seacoast, near Paola. Before I was 20, I received the first followers who had come to imitate my way of life. Seventeen years later, when my disciples had grown in number, I established a rule for my community and sought the approval of the Church. W e called ourselves the Hermits of St Francis of Assisi. W e were approved by the Holy See in 1474. In 1492, I changed the name of my community to "M inims" because I wanted us to be known as the least (minimi) in the household of God. I wanted us to imitate Francis of "Fix your minds on Assisi's humility. I wanted us to observe the vows of poverty, the passion of our chastity and obedience, but also a perpetual Lenten fast. I believed that in order to grow spiritually we should mortify Lord Jesus Christ… ourselves heroically. He himself gave us an example of It was my desire to be a contemplative hermit, yet I perfect patience believed that God was calling me to the apostolic life. I and love. W e, then, began to use the gifts I had received to minister to the are to be patient in people of God. -

Lasallian Calendar

October 16, 2016 Pope Francis declares Saint Brother SOLOMON LE CLERCQ LLAASSAALLLLIIAANN CCAALLEENNDDAARR 22001177 General Postulation F.S.C.- Via Aurelia 476 – 00165 Roma JANUARY 2017 1 Sunday - S. Mary, Mother of God - World Day of Peace 2 Monday Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzen, bishops , doctors 3 Tuesday The Most Holy Name of Jesus 4 Wednesday Bl. Second Pollo, priest. ex-pupil in Vercelli (Italy) 5 Thursday St. Telesphorus, pope 6 Friday - The Epiphany of the Lord Missionary Childhood Day – 1st Friday of the month 7 Saturday St. Raymond of Peñafort 8 Sunday - The Baptism of Jesus Christ St. Laurence Giustiniani 9 Monday St. Julian 10 Tuesday St. Aldus 11 Wednesday St. Hyginus, pope 12 Thursday St. Modestus 1996: Br. Alpert Motsch declared Venerable 13 Friday St. Hilary of Poitiers, bishop, doctor 14 Saturday St. Felix of Nola 15 Sunday II in Ordinary Time Day of Migrants and Refugees - St. Maurus, abbot 16 Monday St. Marcellus I, pope and martyr 17 Tuesday St. Anthony abbot 18 Wednesday St. Prisca 19 Thursday Sts. Marius and family, martyrs 20 Friday Sts. Fabian, pope and Sebastian, martyrs 21 Saturday St. Agnes, virgin and martyr 22 Sunday III in Ordinary Time St. Vincent Pallotti 23 Monday St. Emerentiana 24 Tuesday St. Francis de Sales, bishop and doctor 25 Wednesday - Vocation Day Conversion of St. Paul 26. Thursday – Sts. Timothy and Titus 1725: Benedict XIII approves the Institute by the Bull “In Apostolicae Dignitatis Solio 1937: Transfer to Rome of the relics of St. JB. de La Salle 27 Friday St. Angela Merici, virgin 28 Saturday St. -

Mission to North America, 1847-1859

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2008 Copyright © 2008 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Preface to Volume 6 ix Introduction xi Chapter 1 April—June 1847 1 Chapter 2 July—August 1847 45 Chapter 3 September—December 1847 95 Chapter 4 1848—1849 141 Chapter 5 1850—1859 177 List of Illustrations 197 List of Documents 199 Index 201 ix Preface to Volume 6 Volume 6 of Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Ger- hardinger includes documents from the years 1847 through 1859 that speak of the origins and early development of the mission of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in North Amer- ica. -

Vol.5-1:Layout 1.Qxd

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 5 Living Branches 1859—1867 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2009 Copyright © 2009 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Preface to Volume 5 ix Introduction xi Chapter 1 1859 1 Chapter 2 1860 39 Chapter 3 1861 69 Chapter 4 1862 93 Chapter 5 1863 121 Chapter 6 1864 129 Chapter 7 1865 147 Chapter 8 1866 175 Chapter 9 1867 201 List of Documents 223 Index 227 ix Preface to Volume 5 Volume 5 of Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Ger- hardinger includes documents from the years 1859 through 1867, a time of growth for the congregation in both Europe and North America. -

John Baptist De La Salle: the Formative Years

John Baptist de La Salle The Formative Years John Baptist de La Salle as a young canon John Baptist de La Salle The Formative Years Luke Salm, FSC 1989 Lasallian Publications Romeoville, Illinois This volume is dedicated to the memory o/two extraordinanly gifted teachers, Brother Charles Henry, FSC, and the Reverend Eugene M. Burke, CSP, who contn'buted respectively and in a significant way to the classical and theological education 0/the author in his formative years. Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the Unired States and Toronro Editorial Board Joseph Schmidr, FSC Francis Huether, FSC Executive Director Managing Editor Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC William Quinn, FSC Ronald Iserti, FSC Luke Salm, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC Gregory Wright, FSC ---+--- John Baptist de La Salte: The Formative Years is volume I of Lasallian Resources: Contemporary Documents. The etching on the cover and on page 47 is of rhe Sorbonne, from Views 0/France and Italy, by Israel Silvestre and various anists. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of Robert H. Thayer. Used with permission of the Narional Galley. Copyrighr © 1989 by Christian Brothets Conference All righrs reserved Primed in rhe United States of America Library of Congress catalog card number 88-83713 ISBN 0-944808-03-4 Cover: The chapel of the Sorbonne. Contents List of Illustrations ....................... .. VIl List of Abbreviations IX Pteface ....................... XI Introduction 1. The College des Bons-Enfants 7 2. Student Cletic .................... 23 3. Theological Student ............................... 39 4. Student Seminarian . ... ...•... 72 5. Candidate fot Ordination ....................... -

Thirteen Fridays in Honor of St. Francis of Paola

Thirteen Fridays in Honor of St. Francis of Paola Friday January 3rd 2014 to Friday, March 28th 2014 at 7:00 p.m. in our Chapel Wednesday, April 2nd 2014 Mass and Reception to Follow St. Francis was born in the tiny village of Paola, Italy. *(His image in stained glass can be viewed above the altar of Saint Anthony’s Church.) Paola is located near the Tyrrhenian Sea, in Calabria, and is midway between Naples and Reggio, Italy. His parents, Giacomo and Vienna d’Alessio, were remarkable for the holiness of their lives. Remaining childless for some years after their marriage they had recourse to prayer, especially commending themselves to the intercession of St. Francis of Assisi. Three children were eventually born to them, the eldest of whom was Francis. Saint Francis of Paola was born on March 27, 1416 and died on Good Friday, April 2, 1507. His parents attributed his birth to the intercession of St. Francis of Assisi. From the beginning, Francis was a famous wonder worker on behalf of the poor and oppressed. He used common objects to work miracles so that everyone understood that it was God who really restored health or solved problems. Francis of Paola himself started the 13 Fridays devotion in honor of Jesus and his twelve disciples. Francis chose Friday to honor the passion of Jesus. It was after the death of Francis that the Order of Minims changed the 13 Fridays devotion in honor of Francis of Paola. Join us for the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament in the Monastic Format; Prayer attributed to the 13 Fridays, the Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the reposing of the Blessed Sacrament. -

Notre Dame “Cousins” Share Roots, Charism Throughout the World. by Ruth Shanklin Jackson, Mankato Communications Director NAMA NEWS, March 2006

Notre Dame “Cousins” share Roots, Charism throughout the World. By Ruth Shanklin Jackson, Mankato Communications Director NAMA NEWS, March 2006 Independent congregations, all of whom can trace their origins to Peter Fourier and Alix LeClerc, have met every two or three years since 1983, with the last meeting held in Munich in September 2004. These Notre Dame “cousins” have elements of their charism that have been identified as common to all or most of these congregations, including education, poverty, unity, devotion to Mary and Eucharist. During the 1995 meeting of the Notre Dame “cousins” one of the speakers had used the image of fire in speaking of the nature of charism. At the end of the meeting, one general superior “returned to that image in her evaluation, stating that for her, the association did not represent congregations that have traveled separate ways but women that have been ignited by the same spark and continue to share the light that they have received.” (Sister Patricia Flynn, Circular 64/95, November 21, 1995) The woman who was the impetus for this, Blessed Alix Le Clerc, was convinced that God was calling her to the education of young girls whom she believed were regarded as “worthless straw.” Because no established structures existed for such a vision, she gathered five companions and with St. Peter Fourier, who was the local pastor, made plans for a new religious congregation. The Canonesses of St. Augustine of the Congregation of Notre Dame made their first consecration together on December 25, 1597. In spite of poverty, misunderstanding, and resistance from church authorities, the new venture flourished and spread throughout France and into southern Germany. -

Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 1 Sowing the Seed 1822—1840 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2010 Copyright © 2010 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Letter from Mary V. Maher, SSND ix Foreword by Rosemary Howarth, SSND xiii Preface xv Acknowledgments xix Chronology xxi Preface to Volume 1 xxv Introduction to Volume 1 xxvii Chapter 1 1822—1832 1 Chapter 2 1833—1834 27 Chapter 3 1835 57 Chapter 4 1836 71 Chapter 5 1837 105 Chapter 6 1838 117 Chapter 7 1839 147 Chapter 8 1840 175 List of Documents 209 Index 213 Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger (1797-1879) Illustration by Norbert Schinkmann, 1996. -

The Influence of Father Barré in the Foundation of the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus of Reims.” Translated by Leonard Marsh, Phd

Poutet, Yves. “The Influence of Father Barré in the Foundation of the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus of Reims.” Translated by Leonard Marsh, PhD. AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 10, no. 1 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2019). © Yves Poutet, FSC, DLitt. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for- profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. The Influence of Father Barré in the Foundation of the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus of Reims Yves Poutet, FSC2 Translated from French by Leonard Marsh, FSC3 Father Nicolas Barré was careful to keep his life private, and so he is hardly known by our contemporaries. He was a religious in the Order of Minims who lived for a time in the same building as the famous Father Mersenne in the monastery of Place Royale in Paris. Whereas the Dictionnaire de spiritualité accords him a half column, M. D. Poinsenet gives him no more than five lines in his France religieuse du XVIIe siècle. This latter author was so taken up with the royal aura surrounding the names of Mme de Maintenon and Saint-Cyr, for whom Father Barré served as a pedagogical advisor, that he forgets to mention the originality that distinguishes the disciples of Barré from all the other women educators of the “great century of souls.” It was precisely to care for the souls not of noble girls but of the children of common people that Father Barré founded two teaching congregations of religious women: the Sisters of Providence of Rouen and the Ladies of Saint-Maur whose motherhouse is in Paris.